Fundamentals

You have felt it. The subtle, or perhaps profound, shift in your body’s internal landscape. It may be a persistent fatigue that sleep does not resolve, a change in your mood or mental clarity, or a physical transformation that feels disconnected from your lifestyle.

You sought answers and began a dialogue about hormonal health, possibly starting a protocol like testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) or menopausal hormone therapy. Yet, the results may not align with the promised outcomes. You might look at your lab reports, see numbers within a “normal” range, and still feel that something is fundamentally misaligned.

This experience is valid. Your body is not a standard machine, and its response to hormonal support is deeply personal, written into the very fabric of your biological code.

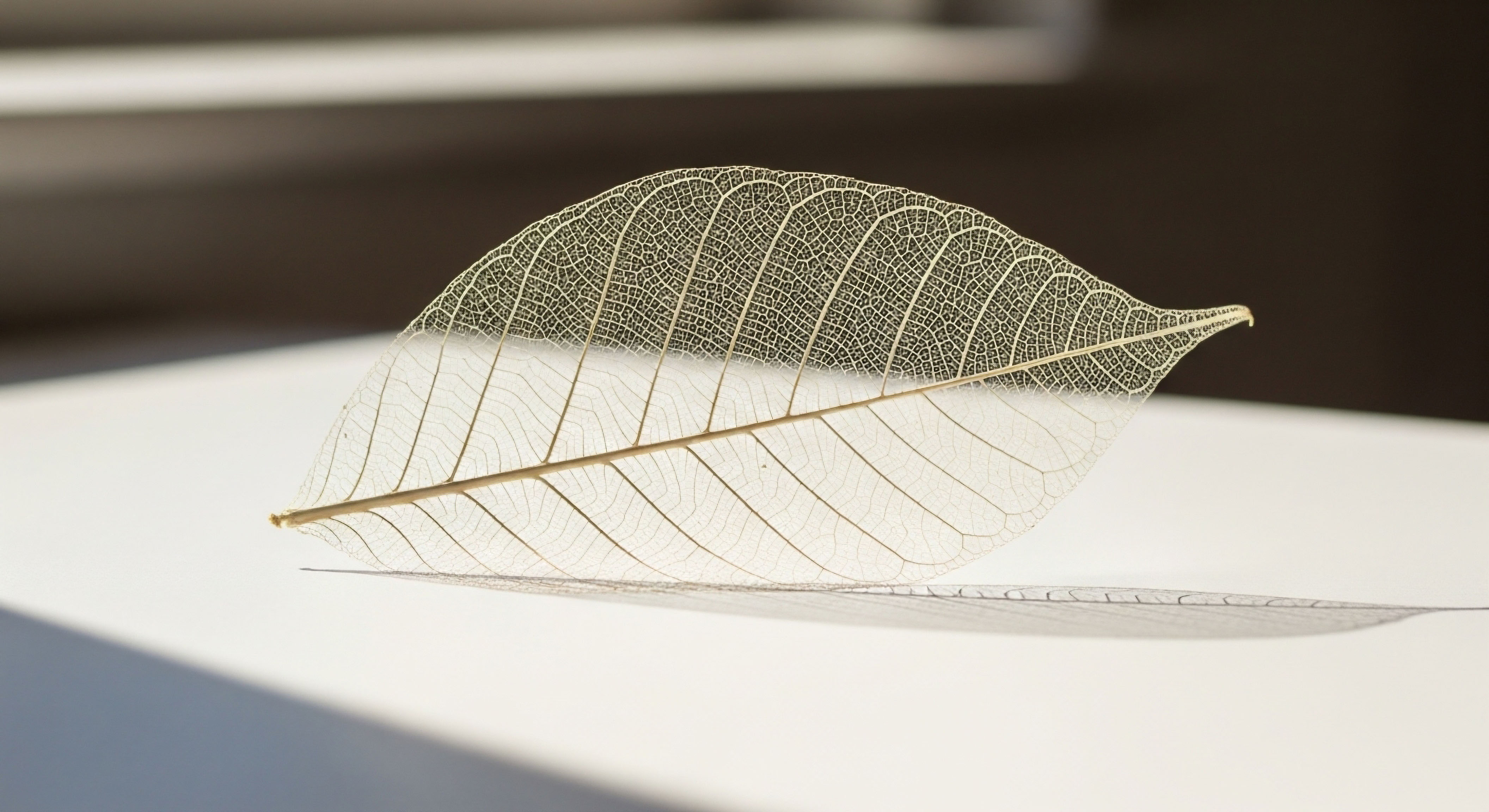

The journey to understanding your health requires moving past population averages and into personal specifics. The core of this personalization lies within your genetics. Your DNA contains the blueprints for every protein in your body, including the enzymes that build and break down hormones and the receptors that receive their messages.

These blueprints are not identical for everyone. Small, common variations called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, create unique versions of these essential proteins. These variations are the reason a single dose or type of hormone therapy can yield dramatically different results from one person to the next. It is the biological explanation for your unique experience.

Your genetic code provides the specific instructions for how your body will build, process, and respond to hormonal signals.

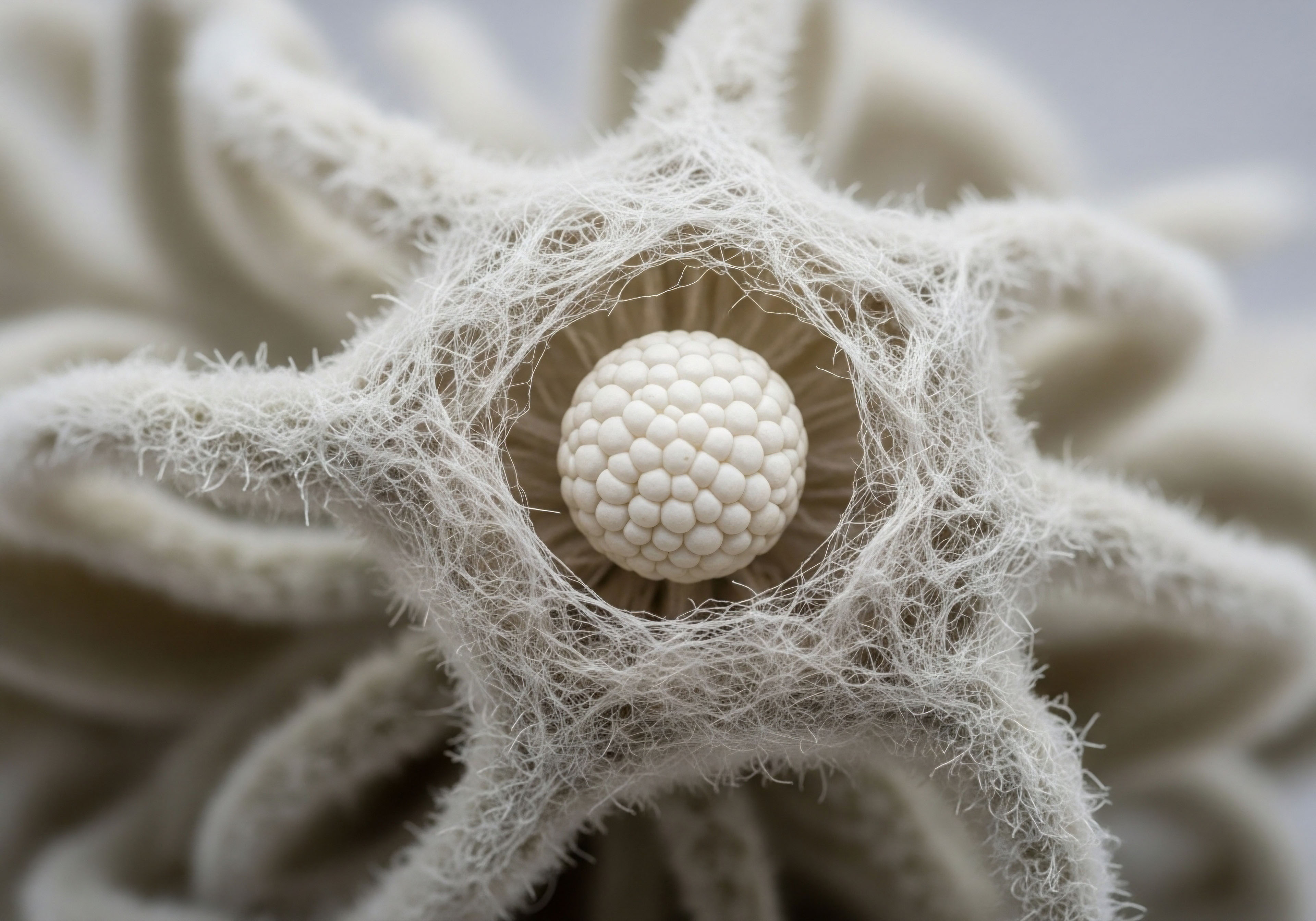

To grasp this, we can visualize the endocrine system as a sophisticated internal communications network. Hormones are the chemical messengers, traveling through the bloodstream to deliver specific instructions to target cells throughout the body. For this communication to be successful, two processes must function correctly ∞ the creation and delivery of the message (hormone metabolism) and the reception of that message (hormone receptor function). Genetic variations influence both of these critical stages.

The Role of Genetics in Hormone Metabolism

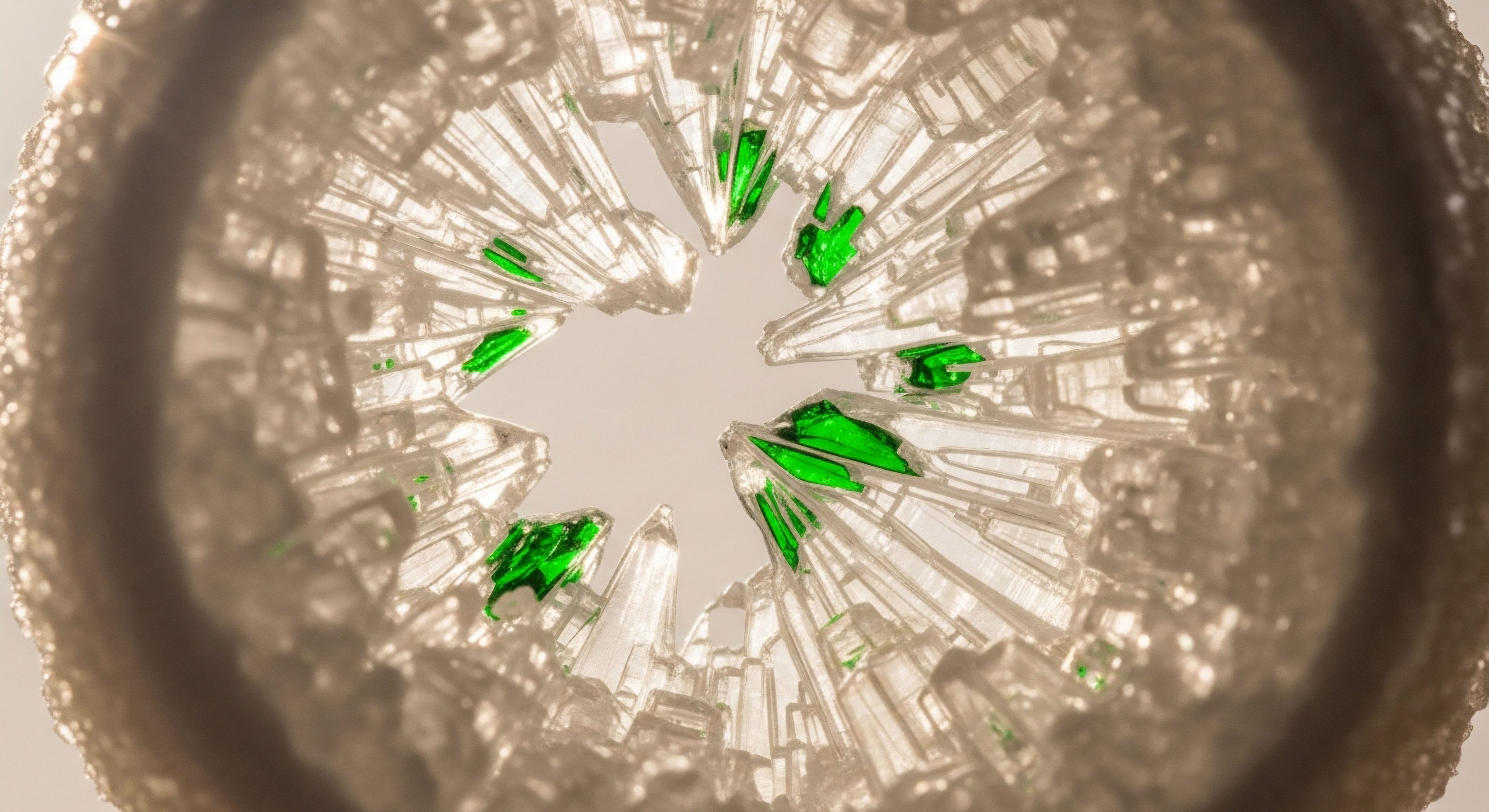

Your body is constantly producing, converting, and clearing hormones in a precise biochemical dance. The enzymes responsible for these conversions are proteins, and the genes that code for them can have significant variations. Consider testosterone. It can be converted into estrogen by an enzyme called aromatase, which is encoded by the CYP19A1 gene.

Some individuals have a genetic variation that makes their aromatase enzyme highly active. If they take testosterone, their body may convert a large portion of it into estrogen, leading to side effects like water retention or mood changes, even on a standard dose.

Conversely, someone with a less active version of this enzyme might need a different protocol to maintain balance. This single genetic point explains why a man on TRT might require an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole while another does not. The same principle applies to how your body processes estrogens, progesterone, and other steroid hormones, dictating your innate hormonal balance and your response to external therapies.

Understanding Hormone Receptor Sensitivity

A hormone’s message is only as effective as the receiver. Hormones exert their effects by binding to receptors on or inside cells, much like a key fitting into a lock. These receptors are also proteins, built from genetic instructions. The gene for the androgen receptor ( AR ), which receives testosterone’s signal, is a prime example.

A well-studied variation in this gene is the length of a repeating segment of DNA called the CAG repeat. Men with a shorter CAG repeat length tend to have androgen receptors that are more sensitive to testosterone. Their cells “hear” the testosterone message more loudly.

Consequently, they might experience symptoms of low testosterone even with blood levels that appear to be in the low-normal range, and they may respond robustly to therapy. Conversely, a man with a longer CAG repeat has less sensitive receptors. He might need higher circulating levels of testosterone to achieve the same physiological effect.

This genetic difference in receptor sensitivity is a fundamental reason why “normal” lab ranges can be misleading and why treatment must be tailored to the individual’s symptomatic response, which is itself guided by their unique genetic makeup.

Intermediate

Advancing from the foundational knowledge that genetics dictates hormonal response, we can now examine the specific clinical pathways and the genes that govern them. For any individual undergoing hormonal optimization, understanding their personal genetic landscape provides a powerful tool for interpreting their body’s feedback and refining their therapeutic protocol.

This is the core of pharmacogenomics ∞ the study of how an individual’s genetic makeup affects their response to medical treatments. It allows us to move from a reactive model of adjusting dosages based on side effects to a proactive model that anticipates an individual’s needs. We will investigate the key genes influencing testosterone therapy in men, hormone replacement in women, and the shared metabolic pathways that are critical for both.

Androgen Response and Testosterone Replacement Therapy

The clinical experience of men on testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) is remarkably diverse. One individual may report a significant improvement in energy, libido, and well-being on a modest dose of testosterone cypionate, while another may feel minimal effects on a much higher dose. The primary genetic determinant of this variability lies within the androgen receptor ( AR ) gene.

The Androgen Receptor CAG Repeat

The AR gene, located on the X chromosome, contains a polymorphic region where the DNA sequence ‘CAG’ is repeated multiple times. The number of these repeats directly impacts the sensitivity of the androgen receptor.

- Shorter CAG Repeats (e.g. less than 22) ∞ This configuration typically results in an androgen receptor that is more sensitive to testosterone and its potent metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Men with this variation may be more susceptible to the symptoms of declining testosterone levels with age because their system is accustomed to a strong androgenic signal. They are often the individuals who report the most significant subjective benefits from TRT, as their highly sensitive receptors respond effectively to the restored hormone levels.

- Longer CAG Repeats (e.g. more than 24) ∞ This variation produces a receptor that is less sensitive to androgens. These individuals may require higher baseline levels of testosterone to maintain normal physiological function and may find that standard TRT dosages are insufficient to alleviate symptoms. Their lab results might show high-normal or even elevated testosterone levels, yet they continue to experience symptoms of hypogonadism because the hormonal message is not being received efficiently at the cellular level.

This genetic information is profoundly useful. It helps explain why a specific total testosterone level on a blood test does not always correlate with a man’s experienced vitality. It validates the experience of the man with longer CAG repeats who may require a higher dose to feel optimal, and it informs the clinician to monitor the man with shorter repeats closely for potential androgen-excess side effects.

Variations in the androgen receptor gene directly influence how effectively a man’s body can utilize testosterone, impacting TRT outcomes.

Estrogen Metabolism a Key Factor for Men and Women

The balance between androgens and estrogens is crucial for health in both sexes. The enzyme responsible for converting androgens (like testosterone) into estrogens (like estradiol) is aromatase, encoded by the CYP19A1 gene. Genetic variations in CYP19A1 can significantly alter aromatase activity, directly affecting outcomes in hormone therapy.

How Do CYP19A1 Variations Affect Treatment Protocols?

Certain SNPs in the CYP19A1 gene are associated with increased aromatase expression or activity. For a man on TRT, this can mean a higher rate of conversion of supplemental testosterone into estradiol, potentially leading to side effects such as gynecomastia, fluid retention, and emotional lability.

These are the individuals who are more likely to require co-administration of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole to maintain a healthy androgen-to-estrogen ratio. For a woman, particularly in the perimenopausal and postmenopausal years, variations in CYP19A1 can influence her baseline estrogen levels and how she responds to hormone therapy.

One study identified a specific CYP19A1 variant (rs10046) that was associated with a lower incidence of hot flashes and sweating in women undergoing treatment with an aromatase inhibitor, suggesting a direct link between this gene and the experience of common menopausal symptoms.

The following table outlines key genes and their clinical relevance in hormonal therapies:

| Gene | Function | Genetic Variation | Clinical Implication in Hormone Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Androgen Receptor (AR) | Binds testosterone and DHT to initiate cellular action. | CAG repeat length polymorphism. | Shorter repeats lead to higher receptor sensitivity, potentially increasing response to TRT. Longer repeats cause lower sensitivity, sometimes requiring higher doses for symptomatic relief. |

| CYP19A1 (Aromatase) | Converts androgens to estrogens. | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). | Variants can increase or decrease enzyme activity, affecting estrogen levels. This influences the need for aromatase inhibitors in men on TRT and impacts side effect profiles in women on endocrine therapies. |

| Estrogen Receptor 1 (ESR1) | Binds estrogen to regulate gene expression. | SNPs like IVS1-401. | Affects how tissues respond to estrogen. Certain variants can augment the effects of HRT on cardiovascular markers like E-selectin, personalizing risk and benefit assessment. |

| CYP2D6 | Metabolizes various drugs, including the SERM tamoxifen. | Allelic variants leading to different metabolizer phenotypes (Poor, Intermediate, Extensive). | Critical for converting tamoxifen into its active metabolite, endoxifen. Poor metabolizers may derive less benefit from standard tamoxifen doses, a key consideration in breast cancer treatment. |

Personalizing Female Hormone Therapy

For women, the pharmacogenomic picture involves a complex interplay of genes related to both estrogen and progesterone. The response to menopausal hormone therapy is influenced not only by metabolic enzymes but also by the genetic structure of the hormone receptors themselves.

Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Genes

The ESR1 gene codes for estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), the primary receptor mediating estrogen’s effects in tissues like the uterus, breast, and bone. Polymorphisms in ESR1 can alter the receptor’s structure and function, thereby changing a woman’s response to estrogen therapy.

For example, one polymorphism has been shown to enhance the effect of HRT on certain markers of vascular health, which could be a factor in assessing the cardiovascular implications of therapy for a specific individual. Similarly, genetic variants in the progesterone receptor ( PGR ) gene can interact with combined hormone therapies that include progestins, potentially modifying risks associated with treatment.

The Case of Tamoxifen and CYP2D6

A classic and compelling example of pharmacogenomics in hormonal health is the relationship between the drug tamoxifen and the CYP2D6 gene. Tamoxifen is a Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM) used in the treatment and prevention of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. It functions as a prodrug, meaning it must be metabolized by the body into its active form, endoxifen, to be effective. The CYP2D6 enzyme is the primary catalyst for this conversion.

The CYP2D6 gene is highly polymorphic, with over 100 known variants (alleles). These alleles can result in different levels of enzyme activity, leading to distinct metabolizer phenotypes:

- Poor Metabolizers ∞ These individuals carry two non-functional alleles, leading to very low or absent CYP2D6 enzyme activity. They are unable to effectively convert tamoxifen to endoxifen, resulting in significantly lower concentrations of the active metabolite and potentially reduced therapeutic benefit from standard doses.

- Intermediate Metabolizers ∞ Carrying one reduced-function and one non-functional allele, or two reduced-function alleles, these individuals have diminished enzyme activity and may also have lower endoxifen concentrations.

- Extensive (Normal) Metabolizers ∞ With two fully functional alleles, these individuals metabolize tamoxifen as expected.

- Ultrarapid Metabolizers ∞ Though less common, these individuals have multiple copies of the CYP2D6 gene and exhibit very high enzyme activity.

This genetic information has profound clinical implications. A woman who is a known CYP2D6 poor metabolizer may not be an ideal candidate for tamoxifen therapy, and her clinical team might consider alternative treatments, such as an aromatase inhibitor if she is postmenopausal. Furthermore, this knowledge is crucial for managing drug-drug interactions.

Many common medications, including certain antidepressants like paroxetine and fluoxetine, are potent inhibitors of the CYP2D6 enzyme. Prescribing such a drug to a woman on tamoxifen, even if she is a normal metabolizer by genotype, can phenocopy the poor metabolizer state, effectively blocking tamoxifen’s activation and compromising its efficacy.

Academic

A comprehensive academic examination of how genetic variations modulate responses to hormone therapies requires a systems-biology perspective. The clinical outcome of administering an exogenous hormone is the net result of a multi-stage physiological cascade. This cascade encompasses hormone synthesis, transport in the circulation, cellular uptake, interaction with nuclear receptors, subsequent gene transcription, and eventual metabolic inactivation and clearance.

Polymorphisms in the genes governing any of these steps can create significant inter-individual variability. We will conduct a deep exploration of the complete testosterone lifecycle, from its synthesis to its clearance, as a model for understanding the cumulative impact of an individual’s unique pharmacogenomic profile.

The Pharmacogenomic Profile of Testosterone Response

The efficacy and safety profile of testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) in men is a complex phenotype influenced by a constellation of genetic factors. While the androgen receptor ( AR ) CAG repeat length is a dominant modulator of sensitivity, a full appreciation requires analyzing the entire pathway. This integrated view explains why two individuals with identical AR genotypes can still exhibit divergent clinical responses.

What Are the Genetic Determinants of Circulating Hormone Levels?

Before any exogenous hormone is administered, an individual’s baseline endocrine milieu is already under genetic influence. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which governs endogenous testosterone production, is regulated by a complex feedback system. While specific genetic influences on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulse generation are an area of active research, we have clearer data on the molecules that transport and metabolize steroid hormones.

- Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) ∞ The majority of circulating testosterone is bound to SHBG, rendering it biologically inactive. Only the free fraction is available to enter cells and bind to the androgen receptor. The gene encoding SHBG is polymorphic, and certain variants are associated with higher or lower circulating levels of the protein. An individual with a genetic predisposition to high SHBG levels may have a high total testosterone level but a low free testosterone level, leading to symptoms of hypogonadism. This genetic factor directly impacts the bioavailability of both endogenous and exogenous testosterone.

- 5-Alpha Reductase (SRD5A2) ∞ This enzyme converts testosterone into dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a far more potent androgen. DHT is critical for the development of external male genitalia and for androgenic effects in tissues like the skin and prostate in adulthood. The SRD5A2 gene has polymorphisms that can affect enzyme activity. Variations leading to higher activity can result in a greater conversion of testosterone to DHT, which may increase the risk for androgenic side effects like acne, hair loss, or benign prostatic hyperplasia in men on TRT.

- UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) Enzymes ∞ The UGT family of enzymes, particularly UGT2B17 and UGT2B15, are responsible for the final phase of testosterone metabolism, converting it into a water-soluble form that can be excreted by the kidneys. Deletions or polymorphisms in these genes can significantly alter the rate of testosterone clearance. An individual with a less active UGT profile may clear testosterone more slowly, leading to higher sustained levels of the hormone from a given dose, which could increase efficacy but also the risk of adverse effects.

A Systems-Level View of Hormonal Action and Metabolism

The table below presents a systems-level analysis of the key genetic modulators in the testosterone pathway, illustrating the interconnectedness of these factors.

| Pathway Stage | Key Gene(s) | Function of Encoded Protein | Impact of Genetic Variation on TRT Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transport & Bioavailability | SHBG | Binds and transports testosterone in the blood. | Polymorphisms altering SHBG levels change the free testosterone fraction, affecting how much hormone is available to tissues from a given dose. |

| Potentiation | SRD5A2 | Converts testosterone to the more potent DHT. | Higher activity variants can increase DHT levels, amplifying androgenic effects and potential side effects like hair loss and prostate growth. |

| Cellular Reception | AR | Nuclear receptor that mediates testosterone’s effects. | CAG repeat length determines receptor sensitivity, acting as the primary gain control for the hormonal signal. |

| Conversion to Estrogen | CYP19A1 | Aromatase enzyme, converts testosterone to estradiol. | Higher activity variants increase estrogen production, influencing the need for aromatase inhibitors to manage side effects like gynecomastia. |

| Inactivation & Clearance | UGT2B17, UGT2B15 | Glucuronidation enzymes that prepare testosterone for excretion. | Lower activity variants slow hormone clearance, potentially increasing the half-life and potency of a TRT dose. |

How Does Genetic Testing Inform Clinical Practice in China?

The application of pharmacogenomics in clinical settings, including in China, is a developing field. While the biological principles are universal, the prevalence of specific genetic polymorphisms can vary among different ethnic populations. For instance, the distribution of CYP2D6 alleles differs between Caucasian and East Asian populations, which has direct implications for the standard dosing of drugs like tamoxifen.

In the context of hormone therapies, establishing population-specific data on the prevalence of variants in genes like AR, CYP19A1, and ESR1 is a critical step. The regulatory framework for genetic testing in China is also evolving, with an increasing focus on integrating such data into personalized medicine protocols, particularly in oncology.

For a clinician practicing in this environment, the legal and procedural considerations involve ensuring that any genetic testing is performed by accredited laboratories and that the interpretation of results is based on data relevant to the patient’s ethnic background.

The commercial landscape includes a growing number of companies offering pharmacogenomic testing services, requiring clinicians to vet these providers for quality and accuracy. The procedural implementation involves not just ordering a test, but also providing comprehensive pre- and post-test counseling to explain the implications of the results for the patient’s long-term health management strategy.

An individual’s response to hormone therapy is a composite phenotype derived from multiple genetic inputs across the entire metabolic and signaling cascade.

This integrated pharmacogenomic profile provides a far more sophisticated and accurate predictor of an individual’s response than any single gene analysis. It creates a biological rationale for why a personalized approach is a clinical necessity.

The future of endocrinology and hormonal health lies in the ability to map this genetic profile for each patient, allowing for the proactive design of therapeutic protocols that are optimized for efficacy and minimized for risk.

This approach moves beyond the simple question of “is the patient’s testosterone low?” to the more sophisticated inquiry of “what level and type of hormonal support does this patient’s unique biological system require to function optimally?” The evidence from numerous studies on AR, CYP19A1, ESR1, and CYP2D6 demonstrates that this level of personalization is not merely a theoretical possibility but an emerging clinical reality.

References

- Herold, D. & Behravan, J. (2002). Common estrogen receptor polymorphism augments effects of hormone replacement therapy on E-selectin but not C-reactive protein. Circulation, 105 (16), 1879 ∞ 1882.

- Feigelson, H. S. et al. (2011). The association of polymorphisms in hormone metabolism pathway genes, menopausal hormone therapy, and breast cancer risk ∞ a nested case-control study in the California Teachers Study cohort. Breast Cancer Research, 13 (2), R32.

- Torky, R. (2017). Pharmacogenomics in personalized medicine ∞ menopause perspectives. Climacteric, 20 (4), 301-302.

- Wang, L. et al. (2018). Genetic Variation in the Androgen Receptor Modifies the Association between Testosterone and Vitality in Middle-Aged Men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15 (12), 1736-1745.

- Gennari, L. et al. (2004). An estrogen receptor-alpha gene polymorphism is associated with variations in body weight and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 89 (3), 1335-1341.

- Regan, M. M. et al. (2016). Impact of CYP19A1 and ESR1 variants on early-onset side effects during combined endocrine therapy in the TEXT trial. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 160 (2), 219 ∞ 229.

- Reis, R. et al. (2014). Genetic Variations in the Androgen Receptor Are Associated with Steroid Concentrations and Anthropometrics but Not with Muscle Mass in Healthy Young Men. PLoS ONE, 9 (1), e86235.

- Jahn, W. (2021). androgen receptor mutations. YouTube. Retrieved from video content.

- Cronin-Fenton, D. & Lash, T. L. (2014). Tamoxifen and CYP2D6 ∞ A Controversy in Pharmacogenetics. Advances in Pharmacology, 69, 167-191.

- Moyer, A. M. et al. (2011). Pharmacogenetics of Tamoxifen ∞ Who Should Undergo CYP2D6 Genetic Testing? Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 9 (2), 193-201.

- Lee, A. M. et al. (2005). The association of the estrogen receptor-alpha gene IVS1-397C/T polymorphism with the risk of pre-eclampsia. Journal of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation, 12 (5), 353-357.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2014). CYP19A1 gene. MedlinePlus.

Reflection

You have now journeyed through the intricate biological mechanisms that define your personal relationship with your hormones. This information serves a distinct purpose ∞ to reframe your perspective. The feelings, symptoms, and responses you experience are not arbitrary; they are the logical output of your unique genetic source code interacting with your life and environment. Your body is not failing a standard protocol. Instead, the standard protocol may be failing to account for the complexity of your body.

This knowledge is the starting point for a different kind of conversation about your health. It is the foundation for a true partnership with a clinical guide, one based on your individual data and your lived experience. Consider your own journey. Where have you felt a disconnect between how you feel and what the numbers say?

How might this deeper understanding of your internal architecture shift the questions you ask and the path you choose to follow? The goal is to move forward with a sense of agency, equipped with the understanding that your biology is unique, and so too is your path to vitality.