Fundamentals

Your body is a responsive, interconnected system, and the way you feel each day is a direct reflection of its internal communication. When we discuss hormonal health, we are exploring one of the most sophisticated messaging networks imaginable.

The experience of hormonal fluctuation ∞ be it changes in your cycle, mood, energy, or metabolism ∞ is a valid and important signal from your body. It is an invitation to understand the underlying biological mechanisms that govern your vitality. The conversation about estrogen, in particular, often feels complex.

This hormone, while central to female reproductive health, also plays a critical role in bone density, cardiovascular function, and even cognitive processes for all adults. Regulating its levels is a key aspect of maintaining long-term wellness. One of the most powerful tools we have to influence this regulation is dietary fiber.

The question of whether to source this fiber from whole foods or from supplements is a meaningful one, and the answer lies in understanding how your body processes each.

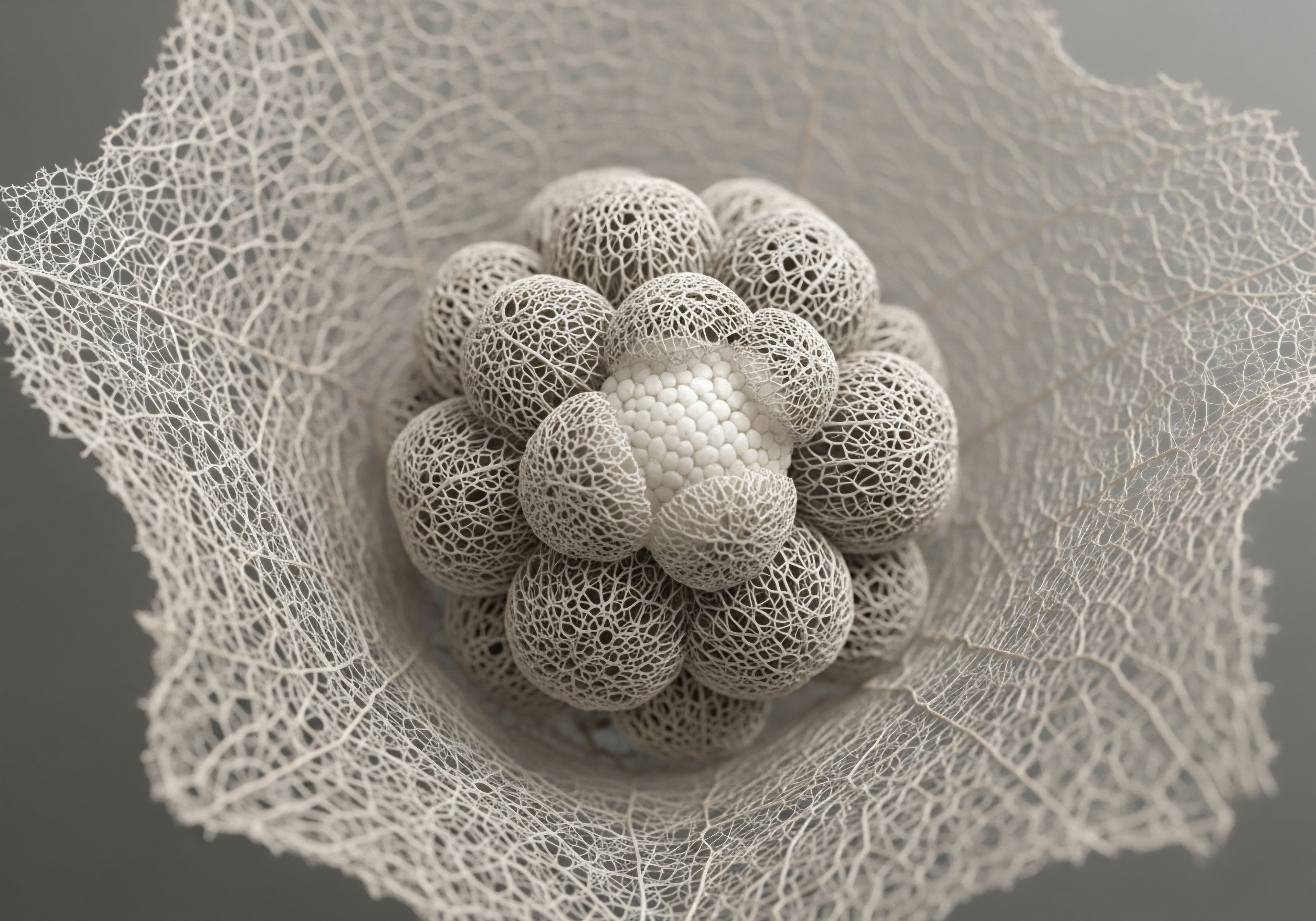

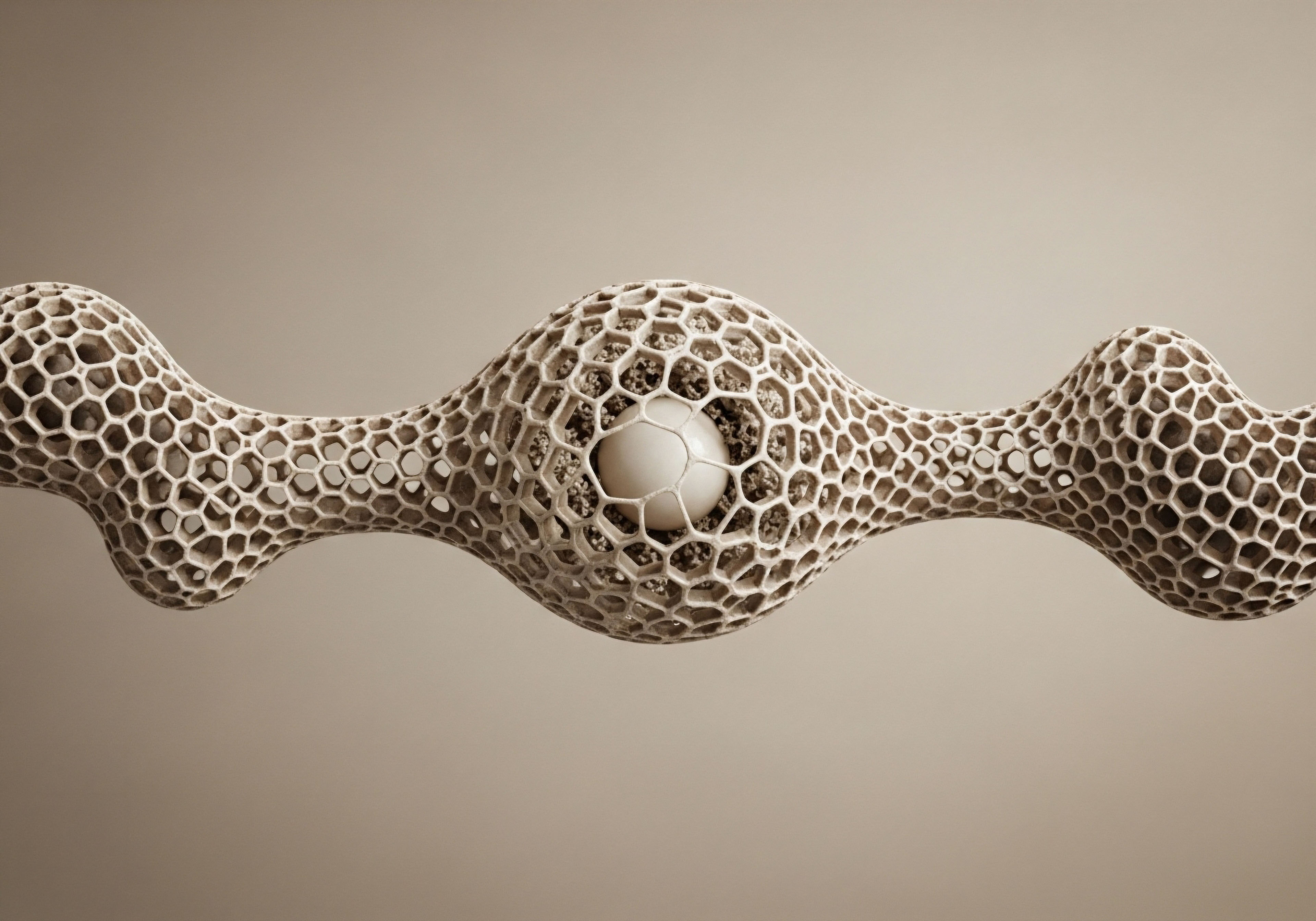

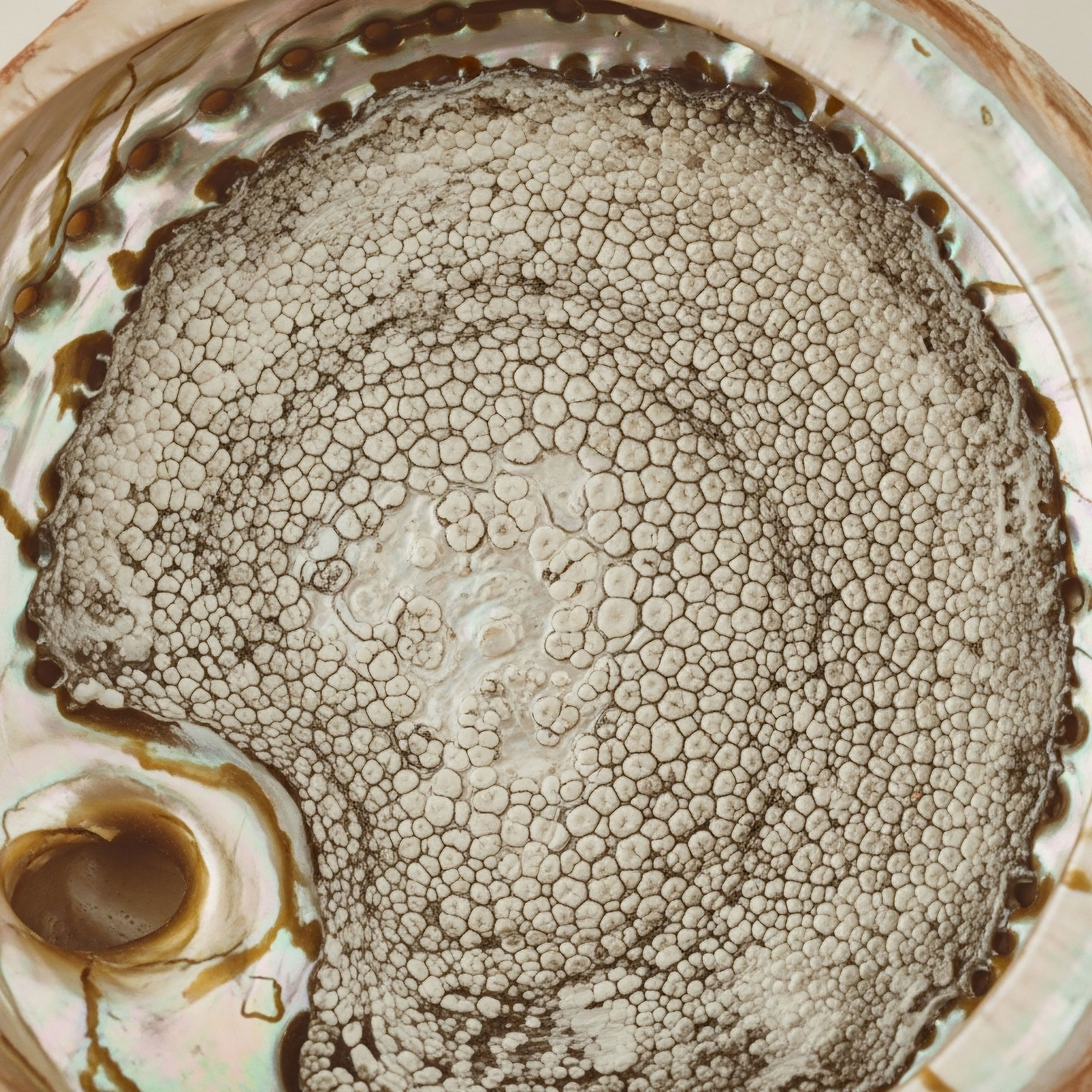

Imagine your digestive tract as a dynamic ecosystem, teeming with trillions of microorganisms. This community, collectively known as the gut microbiome, is a central command center for your health. Within this ecosystem resides a specialized group of bacteria with a unique and critical job ∞ metabolizing and modulating estrogen.

This collection of microbes is called the estrobolome. Its primary function is to produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. After your liver processes estrogens and packages them for removal, they travel to the gut. Here, the beta-glucuronidase produced by your estrobolome can unpack these estrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed into your bloodstream.

A healthy, balanced estrobolome maintains an appropriate level of this enzyme, ensuring that just the right amount of estrogen is recirculated while the excess is safely excreted. An imbalance, however, can lead to either too much or too little estrogen, contributing to the symptoms you may be experiencing.

The gut microbiome contains a specialized set of bacteria, the estrobolome, that directly regulates the body’s estrogen levels.

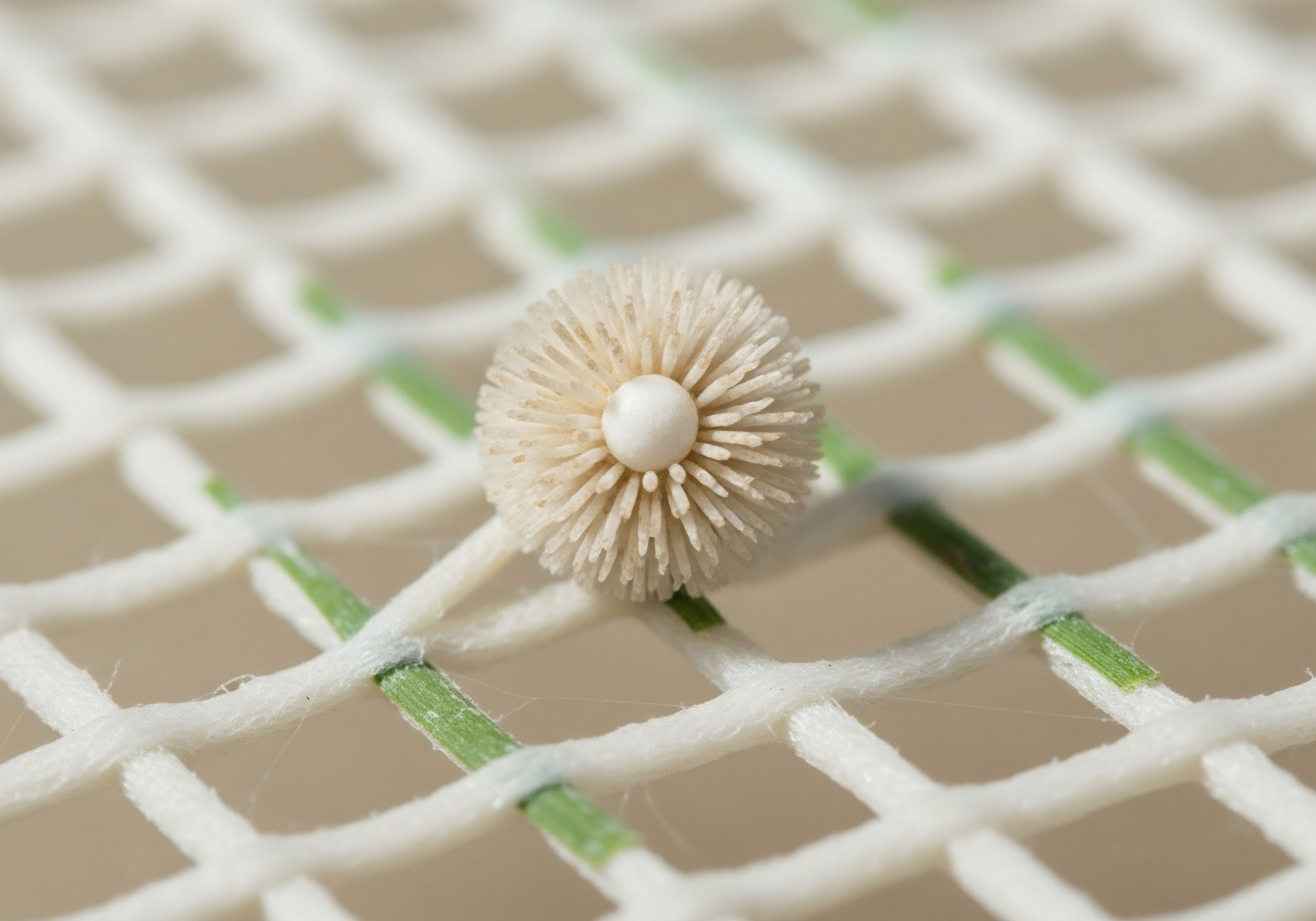

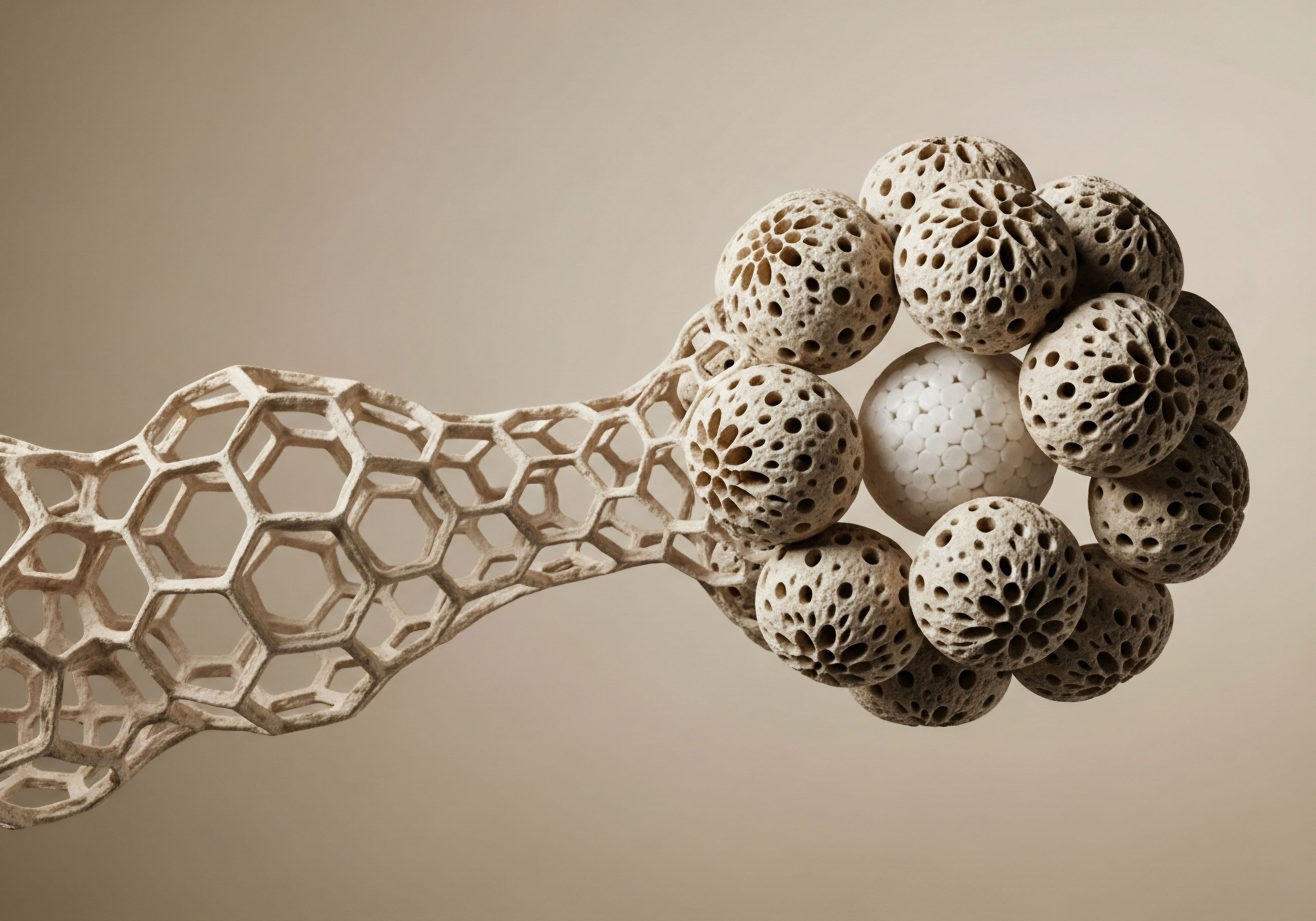

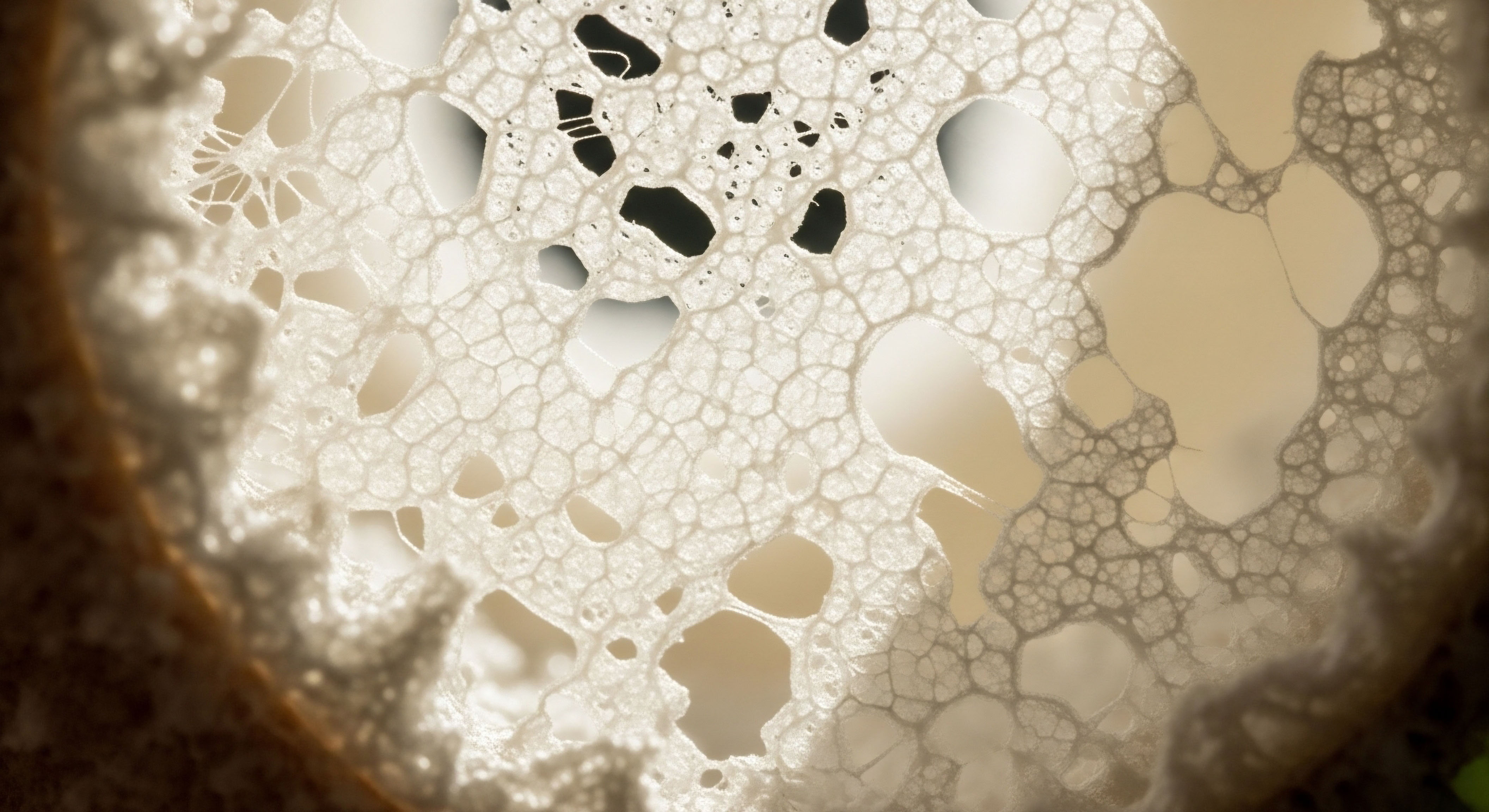

Dietary fiber is the primary fuel for your gut microbiome. It is the raw material your beneficial bacteria use to thrive and perform their essential functions, including the regulation of your estrobolome. Fiber comes in two main forms, and each interacts with your system differently.

Insoluble fiber, found in foods like whole grains and nuts, does not dissolve in water. It adds bulk to your stool, promoting regular bowel movements and helping to physically bind and excrete excess estrogen. Soluble fiber, present in oats, apples, and beans, dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance.

This gel slows down digestion, which can help with blood sugar control, and it is also a preferred food source for many beneficial gut bacteria. When these bacteria ferment soluble fiber, they produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which have wide-ranging benefits for gut health and beyond. Both types of fiber are integral to hormonal balance, working together to ensure the efficient removal of metabolized hormones.

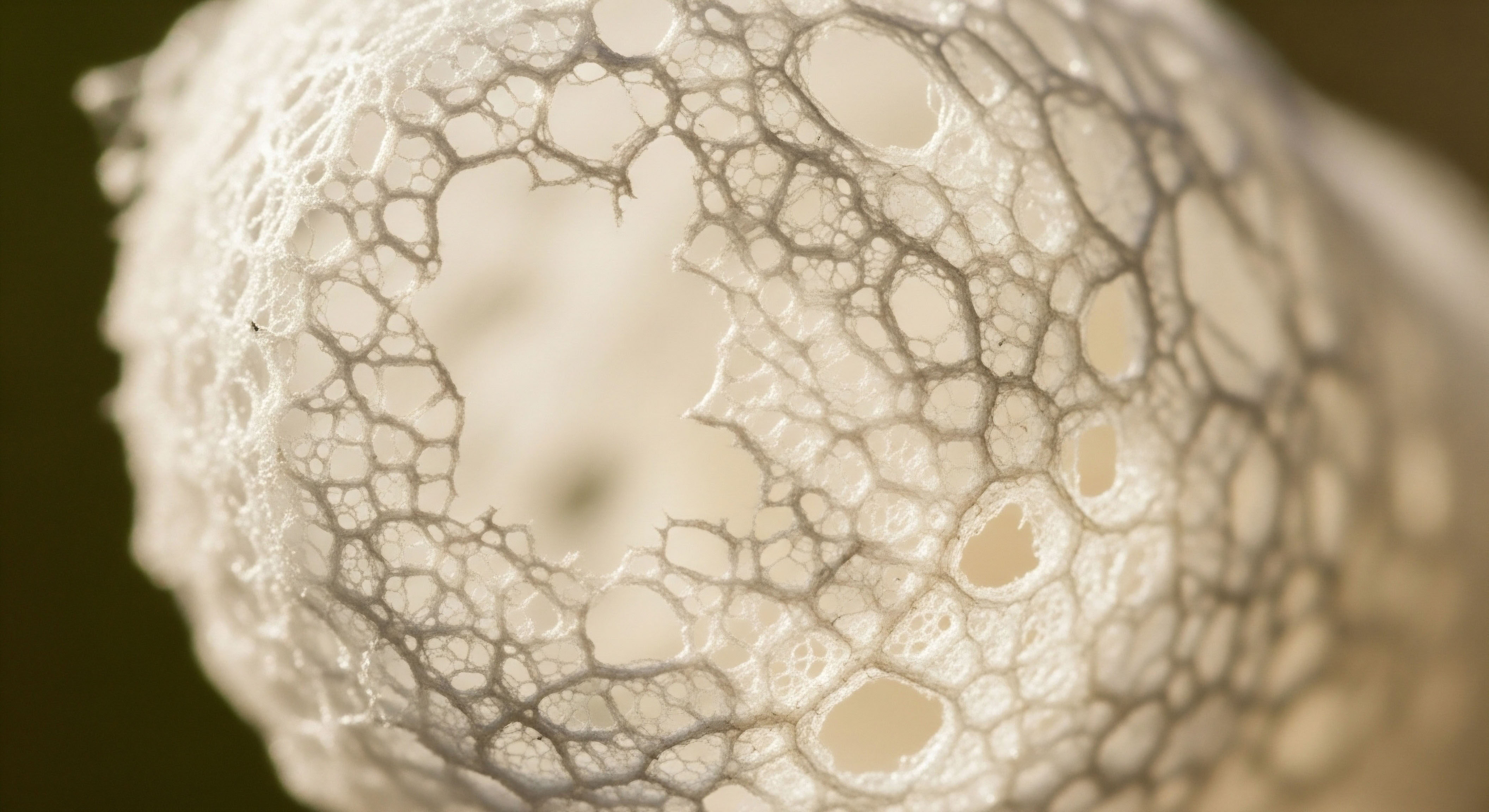

When you consume fiber from whole foods ∞ an apple, a bowl of oatmeal, a serving of lentils ∞ you are receiving more than just the fiber itself. You are ingesting a complex package of micronutrients, phytonutrients, and antioxidants. This food matrix provides a diverse array of compounds that work synergistically.

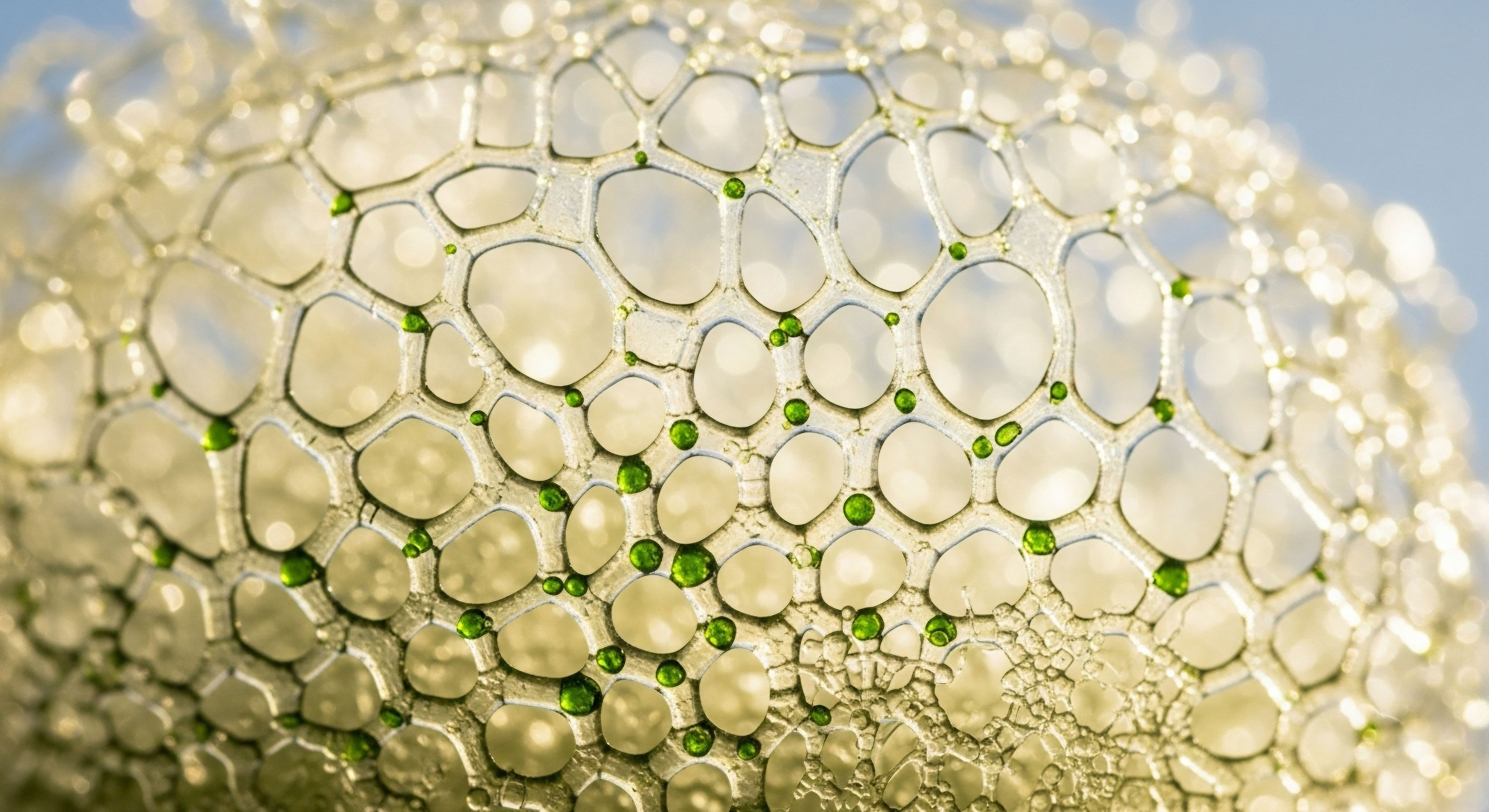

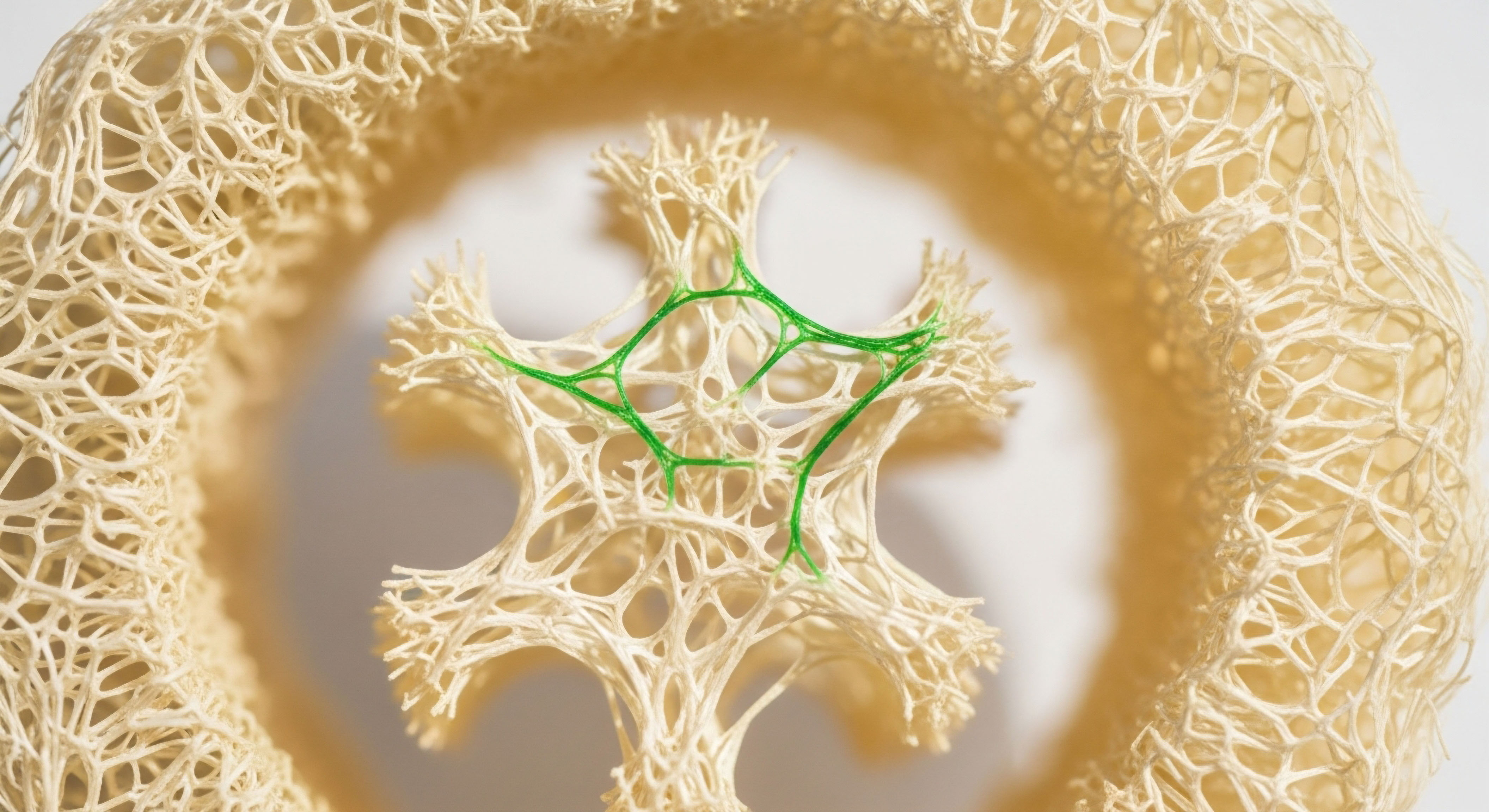

For instance, lignans, a type of phytoestrogen found in flaxseeds, nuts, and whole grains, are converted by your gut bacteria into enterolactone and enterodiol. These compounds have a weak estrogenic effect, allowing them to bind to estrogen receptors and modulate the activity of your body’s own, more potent estrogens.

This complex interplay is difficult to replicate with an isolated supplement. Whole foods provide a rich, varied diet for your microbiome, promoting the diversity of species needed to maintain a healthy and resilient estrobolome. This diversity is the foundation of a well-regulated hormonal system.

Intermediate

To truly grasp the distinction between whole food fiber and supplemental fiber in the context of estrogen regulation, we must examine the specific biochemical interactions that occur within the gastrointestinal system. The journey of estrogen from production to excretion is a multi-step process, and fiber intervenes at a critical juncture.

Your ovaries, adrenal glands, and adipose tissue produce estrogens, which then circulate throughout the body to carry out their functions. Subsequently, they travel to the liver for detoxification. In the liver, through a process called glucuronidation, estrogens are conjugated, or bound, to another molecule.

This conjugation effectively deactivates the estrogen and prepares it for elimination from the body via bile, which is secreted into the intestine. This is where the estrobolome takes center stage. The collection of gut microbes that constitute the estrobolome produces beta-glucuronidase, an enzyme that can sever the bond created in the liver.

This deconjugation process reverts estrogen back to its active form, allowing it to be reabsorbed through the intestinal wall and re-enter circulation. The activity level of your beta-glucuronidase is a key determinant of your circulating estrogen levels.

The Mechanism of Fiber’s Influence

Dietary fiber influences this process through several distinct mechanisms. Firstly, certain fibers, particularly insoluble types, increase fecal bulk and decrease transit time. This mechanical action accelerates the excretion of conjugated estrogens in the stool, reducing the window of opportunity for beta-glucuronidase to act upon them.

Secondly, soluble fibers, especially those that are highly fermentable, provide the substrate for beneficial gut bacteria. As these bacteria ferment the fiber, they produce short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which helps to maintain a healthy gut lining and can lower the pH of the colon.

This lower pH environment is less favorable for the activity of beta-glucuronidase. Therefore, a diet rich in diverse, fermentable fibers can help to modulate the estrobolome, favoring a bacterial composition that supports healthy estrogen metabolism.

Fiber’s modulation of estrogen is a two-part process involving the physical removal of hormones and the biochemical alteration of the gut environment.

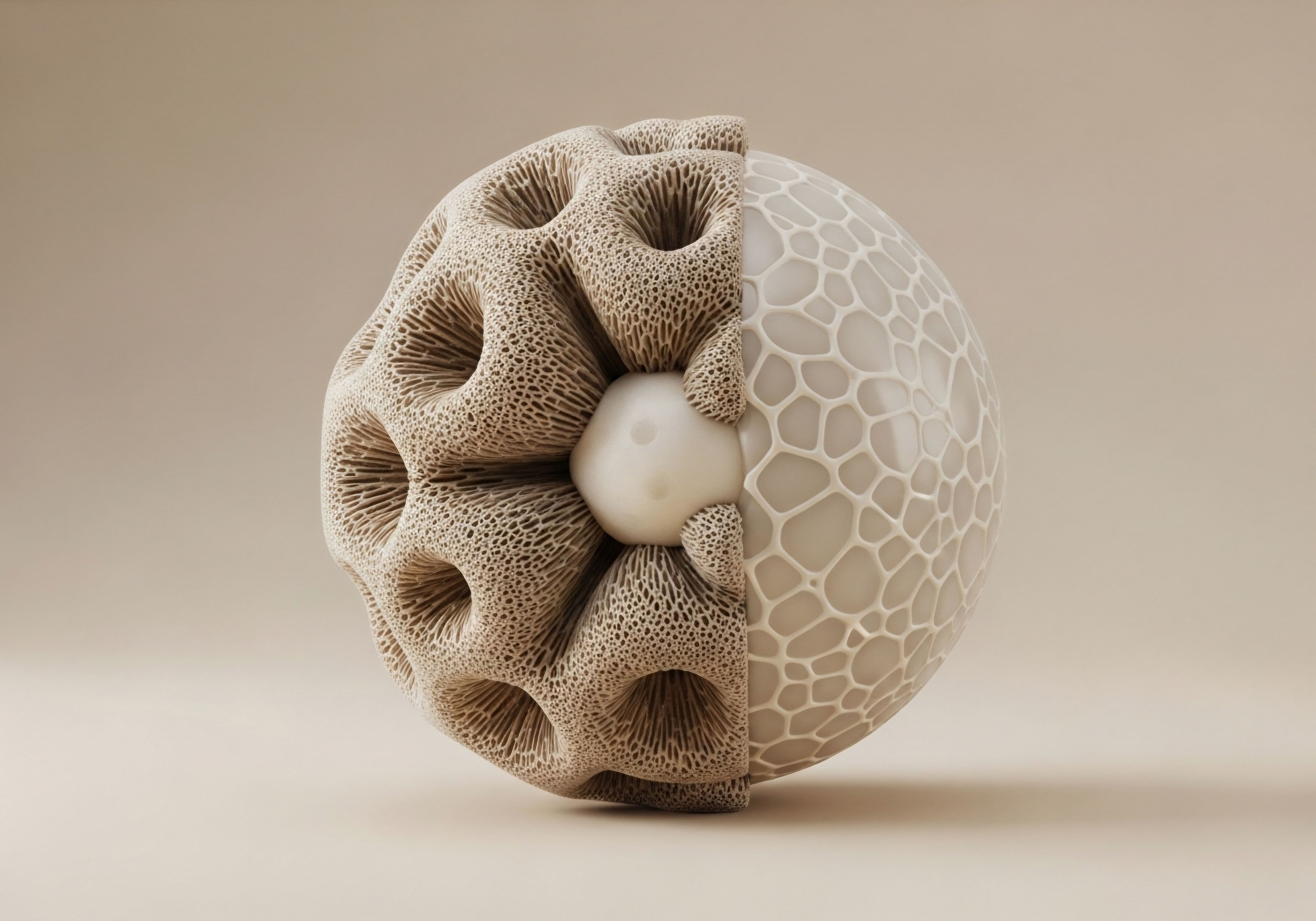

This brings us to the core of the comparison. Whole foods deliver a complex and varied array of fiber types. A single serving of beans, for example, contains a mix of soluble and insoluble fiber, along with resistant starch, which also functions as a prebiotic.

This diversity feeds a wider range of microbial species, promoting a robust and balanced microbiome. In contrast, most fiber supplements consist of a single, isolated fiber type, such as psyllium husk (a mix of soluble and insoluble fiber), methylcellulose (soluble, non-fermentable), or inulin (soluble, highly fermentable). While these supplements can be effective for specific goals, such as improving bowel regularity or lowering cholesterol, their impact on the intricate ecosystem of the estrobolome is more targeted and less holistic.

How Do Lignans from Whole Foods Affect Estrogen?

Furthermore, whole foods provide compounds that supplements lack. Lignans, found abundantly in flaxseeds, sesame seeds, and cruciferous vegetables, are a prime example. These plant-based polyphenols are converted by the gut microbiota into enterolignans, primarily enterolactone and enterodiol. These metabolites possess a structure similar to estradiol, allowing them to bind to estrogen receptors.

Their estrogenic activity is weak, so in situations of high estrogen, they can act as antagonists, blocking the more potent endogenous estrogens from binding to their receptors. In situations of low estrogen, they can provide a mild estrogenic signal. This adaptogenic quality of lignans, entirely dependent on a healthy gut microbiome for its activation, showcases the sophisticated synergy that exists in whole foods. An isolated fiber supplement, while beneficial for transit time, cannot replicate this nuanced biochemical modulation.

A Comparative Look at Fiber Sources

To illustrate these differences, consider the following table comparing various fiber sources:

| Fiber Source | Primary Fiber Type(s) | Key Mechanisms of Action | Associated Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flaxseeds | Soluble and Insoluble | Binds estrogen for excretion, provides lignans for conversion to enterolignans. | Lignans, Omega-3 Fatty Acids |

| Psyllium Husk | Soluble and Insoluble | Forms a viscous gel, increases stool bulk and water content, normalizes transit time. | Primarily isolated fiber |

| Oats | Soluble (Beta-glucan) | Forms a gel, fermented by gut bacteria to produce SCFAs, lowers beta-glucuronidase activity. | Avenanthramides (antioxidants) |

| Inulin Supplement | Soluble (Fructan) | Highly fermentable prebiotic, stimulates growth of Bifidobacteria. | Isolated fiber |

| Cruciferous Vegetables | Insoluble and Soluble | Increases stool bulk, provides compounds that support liver detoxification pathways. | Indole-3-carbinol, Sulforaphane |

While a psyllium supplement can be an excellent tool for improving gut motility, a diet rich in flaxseeds, oats, and cruciferous vegetables offers a multi-pronged approach to estrogen regulation. It supports efficient excretion, modulates the enzymatic activity of the estrobolome, and provides phytoestrogenic compounds that help to buffer hormonal fluctuations. The choice is about the desired level of intervention ∞ a targeted mechanical or prebiotic effect from a supplement, versus a comprehensive, systems-based approach from whole foods.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of fiber’s role in estrogen modulation requires moving beyond general principles and into the specific, often variable, interactions between fiber subtypes, the gut microbiome’s genomic potential, and host physiology. The central axis of this interaction is the estrobolome, the functional collection of enteric bacterial genes whose products are capable of metabolizing estrogens.

The enzymatic deconjugation of estrogens in the gut, primarily by bacterial β-glucuronidase, is a critical control point in enterohepatic circulation, directly influencing the systemic bioavailability of estrogens. An elevated activity of β-glucuronidase is associated with an increased reabsorption of deconjugated estrogens, leading to higher circulating levels. This has been implicated in the pathophysiology of estrogen-dependent conditions. Dietary fiber interventions, whether from whole foods or supplements, aim to modulate this system, but their efficacy and mechanisms are heterogeneous.

Soluble versus Insoluble Fiber a Deeper Look

The traditional classification of fiber into soluble and insoluble categories provides a useful, albeit simplistic, framework. Insoluble fibers, such as cellulose and lignin, contribute to increased fecal mass and reduced colonic transit time. This effect is largely mechanical; by accelerating the passage of intestinal contents, it curtails the time available for bacterial β-glucuronidase to deconjugate estrogens, thereby promoting their fecal excretion.

Soluble fibers, such as pectins, beta-glucans, and gums, form viscous gels in the small intestine, which can delay gastric emptying and slow nutrient absorption. More importantly, many soluble fibers are readily fermented by the colonic microbiota. This fermentation yields short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyrate, propionate, and acetate.

Butyrate, the primary energy source for colonocytes, has been shown to downregulate the expression of β-glucuronidase in certain bacterial species and lower the luminal pH, creating an environment that is suboptimal for the enzyme’s activity. This demonstrates a direct biochemical modulation of the estrobolome’s functional output.

The differential impact of fiber on estrogen lies in its molecular structure, which dictates its fermentability and subsequent influence on the gut’s enzymatic landscape.

However, the source of the fiber introduces a significant layer of complexity. Whole foods provide a complex matrix of different fiber types and bioactive compounds. For example, flaxseed is a rich source of both soluble and insoluble fiber, but it also contains high concentrations of the lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG).

Upon ingestion, SDG is metabolized by intestinal bacteria into the enterolignans enterodiol and enterolactone. These phytoestrogens exhibit selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) activity. They have a high affinity for estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) and a lower affinity for estrogen receptor alpha (ERα).

Their ability to act as ER antagonists in tissues with high levels of endogenous estrogens, such as the breast tissue in premenopausal women, is a key mechanism by which they may exert protective effects. This intricate interaction, involving both the fiber and the co-passenger lignans, cannot be replicated by a pure psyllium or methylcellulose supplement.

What Is the Clinical Evidence?

Clinical trials comparing fiber supplements to whole food sources in the context of estrogen regulation are limited, but studies on individual fiber types provide valuable insights. A randomized controlled trial might compare a high-fiber diet derived from whole foods against a low-fiber diet supplemented with an isolated fiber like psyllium to match the total fiber intake of the whole-food group.

The expected outcome would be that while both groups might show some reduction in circulating estrogens due to improved transit, the whole-food group would likely exhibit a more significant modulation of the estrobolome’s composition and enzymatic activity, along with measurable levels of beneficial metabolites like enterolactone.

A study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that high-fiber diets were associated with lower circulating estrogen concentrations, likely due to reduced β-glucuronidase activity and decreased reabsorption. Another study highlighted that each 5-gram per day increase in total fiber intake was associated with a notable decrease in hormone concentrations, including estradiol.

Comparative Analysis of Fiber Intervention Studies

The following table summarizes findings from representative studies on fiber and estrogen metabolism:

| Study Focus | Intervention | Key Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioCycle Study | Observational study of dietary fiber intake in premenopausal women. | Higher total fiber intake was inversely associated with concentrations of estradiol, progesterone, LH, and FSH. | Demonstrates a dose-dependent relationship between fiber intake and systemic hormone levels. |

| Postmenopausal Women Study | Cross-sectional analysis of dietary fiber and the fecal microbiota. | Higher fiber intake was associated with alterations in gut microbiota composition and a trend toward lower serum estrogen levels. | Supports the role of fiber in modulating the estrobolome to influence estrogen metabolism. |

| Lignan/Flaxseed Trials | Intervention with flaxseed supplementation. | Increased urinary excretion of enterolignans, modulation of estrogen metabolism, and in some studies, reduced breast cancer risk. | Highlights the unique benefits of lignan-rich whole foods beyond their fiber content. |

| Psyllium Supplement Trials | Randomized controlled trials of psyllium for constipation or metabolic syndrome. | Effective at improving bowel regularity and some metabolic markers, but direct effects on estrogen are less studied. | Shows the utility of supplements for specific mechanical or metabolic goals, but not comprehensive hormonal modulation. |

Ultimately, the superiority of whole food fiber sources for the purpose of estrogen regulation stems from their biochemical complexity. They provide a diverse substrate for the gut microbiome, promoting a resilient and balanced estrobolome. They also deliver a suite of bioactive compounds, such as lignans and other polyphenols, that act synergistically with the fiber to modulate hormonal signaling pathways.

While fiber supplements can be a useful adjunct for increasing total fiber intake and addressing specific issues like constipation, they represent a reductionist approach. For a comprehensive strategy aimed at optimizing the intricate system of estrogen metabolism, a diet rich in a variety of whole plant foods remains the more physiologically astute choice.

- Whole Foods ∞ Offer a complex synergy of various fiber types, vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients like lignans, which collectively support both mechanical excretion and biochemical modulation of estrogen.

- Supplements ∞ Provide a concentrated, isolated form of fiber, which can be effective for targeted outcomes like increasing fecal bulk (e.g. psyllium) or feeding specific beneficial bacteria (e.g. inulin), but lack the holistic biochemical profile of whole foods.

- Microbiome Diversity ∞ The variety of fibers in a whole-food diet promotes a more diverse and resilient gut microbiome, which is crucial for maintaining a healthy estrobolome and balanced beta-glucuronidase activity.

References

- Zengul, Ayse G. “Exploring The Link Between Dietary Fiber, The Gut Microbiota And Estrogen Metabolism Among Women With Breast Cancer.” UAB Digital Commons, 2018.

- Gaskins, Audrey J. et al. “Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function ∞ the BioCycle Study.” The American journal of clinical nutrition, vol. 90, no. 4, 2009, pp. 1061-1069.

- “Hormones & Gut Health ∞ The Estrobolome & Hormone Balance.” The Marion Gluck Clinic, Accessed 2 Aug. 2025.

- “Lignans.” Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Accessed 2 Aug. 2025.

- “The Gut-Hormone Connection ∞ How Your Microbiome Impacts Estrogen Level.” Digbi Health, 22 Jul. 2025.

- Wang, Li-Quan. “Mammalian phytoestrogens ∞ enterodiol and enterolactone.” Journal of Chromatography B, vol. 777, no. 1-2, 2002, pp. 289-309.

- “The Estrobolome ∞ The Gut Microbiome-Estrogen Connection.” Healthpath, 13 Jan. 2025.

- Attaman, J. A. et al. “Randomized clinical trial ∞ mixed soluble/insoluble fibre vs. psyllium for chronic constipation.” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 44, no. 1, 2016, pp. 32-43.

Reflection

Your Unique Biological Blueprint

The information presented here offers a map of the biological terrain connecting your dietary choices to your hormonal state. It provides the coordinates, the pathways, and the mechanisms. Yet, a map is only a guide. Your body is the territory itself, with its own unique history, genetics, and microbial inhabitants.

The knowledge that a flaxseed offers a different quality of interaction than a spoonful of psyllium is empowering. It shifts the focus from a simple question of “more fiber” to a more refined inquiry ∞ “what kind of fiber does my system need right now?” This journey of hormonal recalibration is deeply personal.

The way you feel, the symptoms you notice, and the data from your own lab work are the most important feedback you can receive. Use this clinical understanding as a lens through which to view your own experience, and as a foundation upon which to build a personalized strategy. The path forward is one of partnership ∞ with your body and with knowledgeable guides ∞ to restore the intelligent, balanced function that is your birthright.

Glossary

dietary fiber

fiber from whole foods

gut microbiome

beta-glucuronidase

the estrobolome

estrobolome

insoluble fiber

soluble fiber

they produce short-chain fatty acids

hormonal balance

from whole foods

enterolactone

lignans

whole foods provide

estrogen regulation

estrogen levels

produce short-chain fatty acids

estrogen metabolism

whole foods

psyllium

enterohepatic circulation

short-chain fatty acids

flaxseed

phytoestrogens

total fiber intake