Fundamentals

The sensation is a familiar one for many. It can feel like a subtle dimming of your own internal light, a cognitive fog that descends without warning, making once-effortless mental tasks feel laborious. Words that were once readily available may now linger just out of reach, and the clear, sharp focus you once took for granted seems to have softened.

This experience of altered mental clarity and emotional landscape is a deeply personal and often disorienting part of the human condition, particularly as our internal hormonal environment shifts over time. Your lived reality of these changes provides the most important data point. It is the starting point for a deeper investigation into the body’s intricate internal communication network, a system where the steroid hormone estrogen functions as a primary regulator of neurological performance and emotional equilibrium.

To comprehend this connection, we must view estrogen as a foundational biological asset for the central nervous system. Its presence and activity extend far beyond reproductive health, directly influencing the structure, function, and resilience of the brain itself.

Estrogen acts as a potent neuroprotective agent, shielding neurons from oxidative stress and cellular damage, which are natural consequences of metabolic processes and aging. This protective quality is fundamental to maintaining long-term brain health.

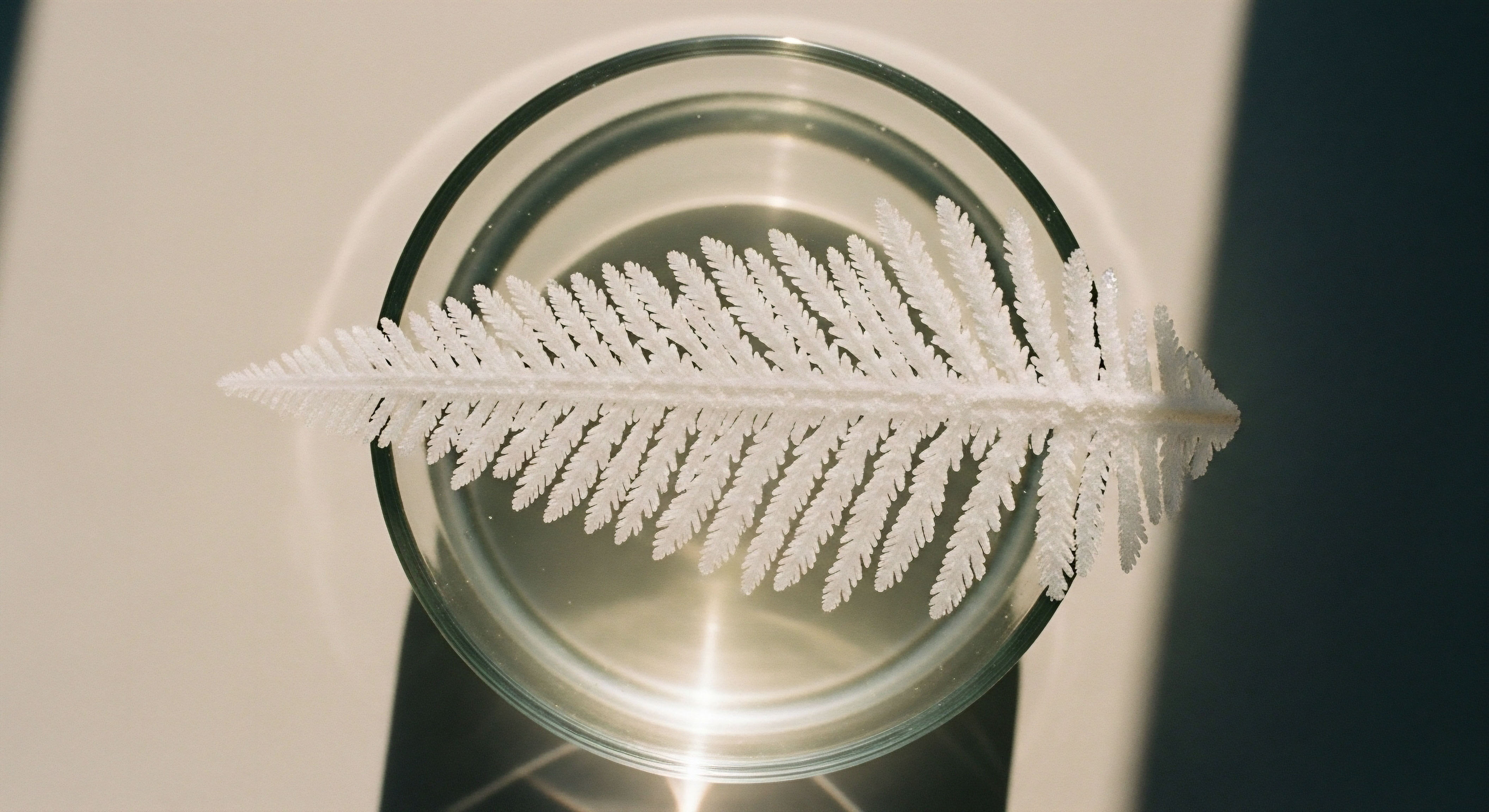

It actively supports the physical architecture of cognition by promoting the growth and maintenance of dendritic spines ∞ the tiny, branch-like structures on neurons that receive signals from other cells. More spines mean more connections, creating a denser, more robust network for transmitting information.

When estrogen levels are optimal, this process of synaptogenesis, or the formation of new synapses, flourishes, particularly in brain regions that are critical for higher-order thinking and memory, such as the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex.

The Architect of Your Cognitive Space

Think of your brain as a complex and dynamic city. The neurons are the buildings and homes, and the synapses are the roads and communication lines that connect them. In this analogy, estrogen is the master architect and urban planner.

It directs the construction of new pathways, ensures the existing infrastructure is well-maintained, and facilitates the efficient flow of information throughout the entire metropolitan area. When this master planner is abundant and active, the city thrives. Communication is rapid, traffic flows smoothly, and new developments (learning and memory formation) are constructed with ease. The cognitive experience is one of clarity, efficiency, and adaptability.

Conversely, when the influence of this planner wanes, as it does during perimenopause and postmenopause, the city’s operations can become less efficient. The maintenance schedules for the neural pathways may become less frequent, leading to a gradual decline in the density of synaptic connections.

The once-bustling communication networks may experience slowdowns, which you perceive as brain fog or difficulty with memory recall. This is a biological reality, a direct consequence of a shift in the biochemical environment that has supported your brain’s peak function for decades. Understanding this mechanism validates the subjective experience of cognitive change. It is a physiological process, a predictable outcome of an altered hormonal state.

Estrogen directly supports the physical structure of thought by fostering the growth of connections between brain cells.

Mood as a Reflection of Brain Chemistry

The influence of estrogen extends deeply into the realm of mood regulation. The stability of our emotional state is governed by a delicate balance of neurotransmitters, the chemical messengers that carry signals between neurons. Estrogen is a key modulator of these systems, particularly serotonin and dopamine, which are central to feelings of well-being, motivation, and emotional resilience.

It helps to fine-tune the production and reception of these critical neurochemicals, ensuring that the brain’s mood-regulating circuits are functioning optimally. When estrogen levels fluctuate or decline, the resulting disruption in these neurotransmitter systems can manifest as increased anxiety, irritability, or the onset of depressive symptoms.

This connection provides a clear biological explanation for the mood shifts that so often accompany hormonal transitions. Your feelings are a direct reflection of your brain chemistry, and that chemistry is profoundly influenced by estrogen.

This foundational knowledge reframes the conversation around hormonal health. The cognitive and emotional symptoms that arise from changing estrogen levels are seen as tangible, measurable biological events. This perspective moves us toward a position of empowerment.

By understanding the underlying mechanisms at play, we can begin to explore strategies for supporting our neurological health, recalibrating our internal environment, and reclaiming a state of cognitive vitality and emotional balance. The journey begins with this recognition ∞ your brain is designed to function with estrogen, and understanding its role is the first step toward optimizing your own cognitive and emotional well-being.

Intermediate

Building upon the foundational understanding of estrogen as a neuroprotective architect, we can now examine the precise mechanisms through which it orchestrates cognitive function and mood. Estrogen’s influence is mediated by specific protein molecules known as estrogen receptors (ERs), which are located throughout the brain. These receptors act as docking stations.

When estrogen circulates through the bloodstream and enters brain cells, it binds to these receptors, activating them and initiating a cascade of downstream cellular events. This binding process is the critical first step that allows estrogen to exert its profound effects on brain chemistry and function.

There are three primary types of estrogen receptors that have been identified in the central nervous system ∞ Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα), Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ), and the G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1). Each receptor type has a unique distribution within the brain and can trigger different cellular responses, allowing for a highly nuanced and region-specific regulation of neural activity.

The Neurotransmitter Control Panel

Estrogen’s regulation of mood and cognition is largely achieved by its ability to modulate the major neurotransmitter systems. It acts like a master technician at the brain’s central control panel, adjusting the levels and activity of serotonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine to maintain a state of operational harmony. Each of these systems is integral to different facets of our mental experience, from our emotional tone to our ability to focus and learn.

The Serotonin System and Emotional Stability

The serotonin system is the brain’s primary regulator of mood, sleep, and appetite. Many individuals experiencing anxiety or depression have disruptions in this system. Estrogen provides significant support to serotonin pathways in several ways. It boosts the synthesis of tryptophan hydroxylase, the enzyme required to produce serotonin from its precursor, tryptophan.

It also appears to limit the activity of monoamine oxidase (MAO), an enzyme that breaks down serotonin in the synapse. The combined effect is an increase in the production and availability of serotonin, which promotes a more stable and positive mood. The fluctuations and ultimate decline in estrogen during perimenopause can lead to a corresponding dysregulation of this system, providing a direct biochemical link to the increased vulnerability for depressive symptoms reported during this life stage.

The Dopamine System and Focused Motivation

Dopamine is the neurotransmitter of motivation, reward, and executive function. It is what drives our ability to focus on a task, plan for the future, and feel a sense of accomplishment. The prefrontal cortex, the brain’s command center for these higher-order cognitive processes, is rich in estrogen receptors.

Estrogen has been shown to enhance dopamine signaling, which can improve working memory and attention. When estrogen levels are high, dopamine activity is supported, contributing to mental sharpness and drive. As estrogen levels fall, the diminished support for the dopamine system can contribute to the feelings of apathy, low motivation, and difficulty with concentration that many report.

The Acetylcholine System and Memory Consolidation

Acetylcholine is fundamentally linked to learning and memory. It is particularly important for the process of memory consolidation, which happens in the hippocampus. Estrogen supports the cholinergic system by increasing the activity of choline acetyltransferase, the enzyme that synthesizes acetylcholine.

This enhancement of the acetylcholine system is one of the key mechanisms through which estrogen facilitates learning and protects verbal memory. The decline in estrogen during menopause can weaken this cholinergic support, contributing to the memory lapses and “brain fog” that are common complaints.

A decline in estrogen can disrupt the brain’s primary chemical systems for mood, focus, and memory.

Hormonal Optimization Protocols a Clinical Perspective

Understanding these mechanisms provides the clinical rationale for hormonal optimization protocols in symptomatic individuals. The goal of such interventions is to restore the biochemical environment in which the brain is designed to thrive. For women in the menopausal transition, this often involves carefully dosed hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

- Estradiol Administration ∞ The primary component of HRT for cognitive and mood symptoms is bioidentical estradiol, which is the same form of estrogen the ovaries produce. It can be administered via transdermal patches, gels, or oral tablets. The objective is to restore estradiol levels to a range that supports optimal neurotransmitter function and synaptic health.

- Progesterone for Balance ∞ For women with an intact uterus, progesterone is prescribed alongside estrogen to protect the uterine lining. Progesterone also has its own effects on the brain, often promoting calming and sleep-inducing effects through its interaction with GABA receptors, another key neurotransmitter system.

- The Role of Testosterone ∞ Women also produce and utilize testosterone, and its decline can contribute to low libido, fatigue, and a diminished sense of well-being. In some cases, a low dose of testosterone cypionate is included in a comprehensive hormonal optimization protocol to address these symptoms and provide additional support for energy and motivation.

The table below summarizes the key estrogen receptors and their primary roles in the brain, illustrating the complexity of estrogen’s actions.

| Receptor | Primary Brain Regions | Key Functions in Cognition and Mood |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) | Hypothalamus, Amygdala, Prefrontal Cortex | Regulates reproductive function, emotional processing (anxiety/fear), and aspects of memory. Involved in neuroprotection and suppressing inhibitory neurotransmission. |

| Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ) | Hippocampus, Prefrontal Cortex, Cerebellum | Crucial for hippocampal-dependent memory and learning. Promotes synaptic plasticity and may have antidepressant-like effects. |

| GPER1 (G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1) | Hippocampus, Cortex, Hypothalamus | Mediates rapid, non-genomic effects of estrogen. Involved in synaptic plasticity, neuroprotection, and rapid signaling cascades that can influence mood and cognition. |

What Is the Critical Window for Intervention?

A significant body of research points to the existence of a “critical window” for initiating HRT to achieve maximum cognitive benefits. This theory suggests that starting hormone therapy close to the onset of menopause, typically within the first 5-10 years, can help preserve brain structure and function.

If initiated later, the brain may have already undergone structural changes, and estrogen receptors may have become less responsive, potentially reducing the therapy’s effectiveness. This highlights the importance of proactive management and early consultation when symptoms first appear. The decision to initiate any hormonal therapy is deeply personal and requires a thorough evaluation of an individual’s symptoms, health history, and goals in consultation with a knowledgeable clinician.

Academic

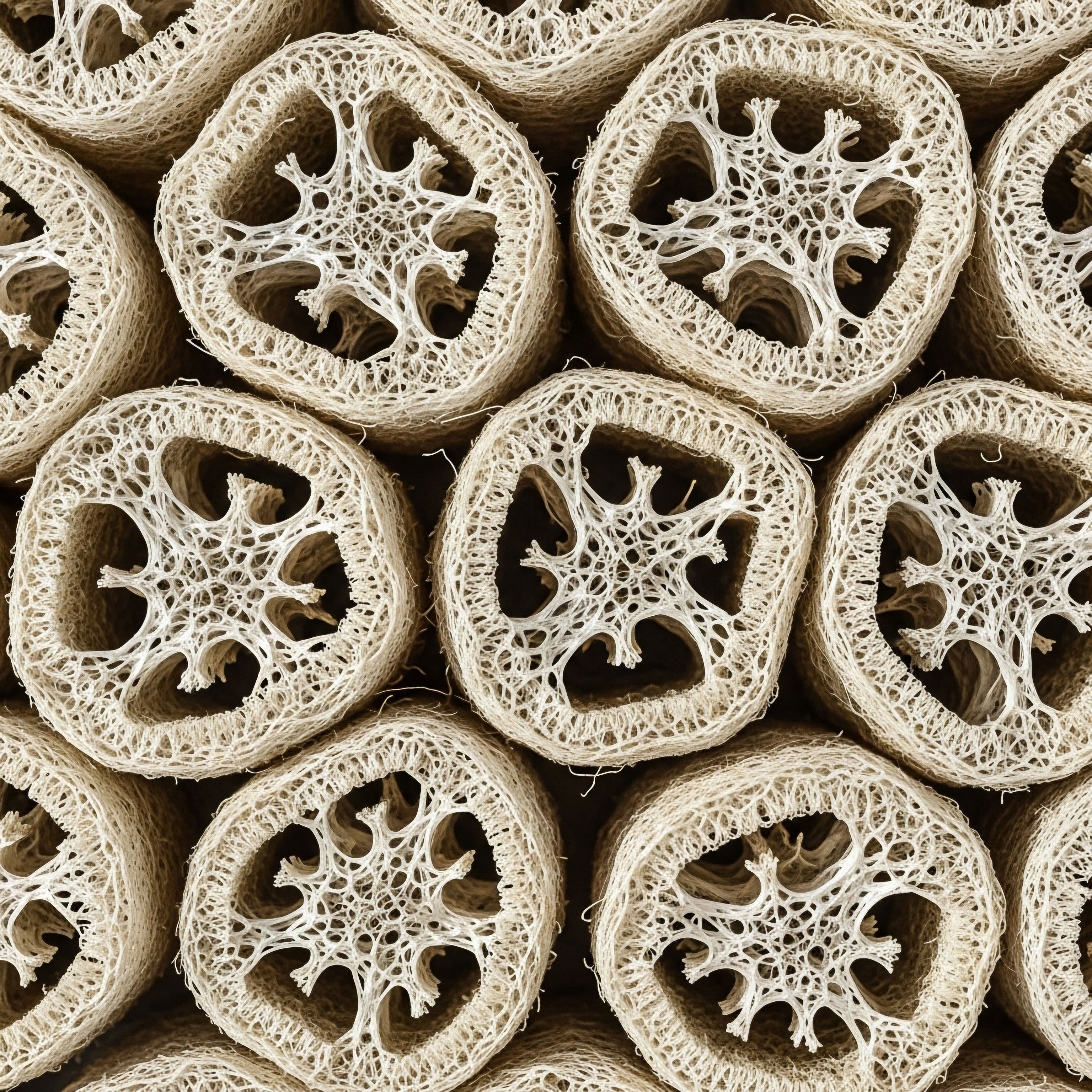

An academic exploration of estrogen’s influence on cognitive function requires a focused analysis of the molecular machinery driving synaptic plasticity. The brain’s capacity to learn and form memories is contingent upon its ability to modify the strength and number of connections between neurons.

This process, known as synaptic plasticity, is most prominent in the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. Estradiol (E2), the most potent form of estrogen, is a master regulator of this process. Its effects are mediated through a combination of classical genomic pathways and rapid, non-genomic signaling cascades that converge to alter neuronal structure and function on a micro-level.

A deep dive into the non-genomic actions of E2, particularly its interaction with glutamate receptors and the activation of intracellular signaling pathways, reveals the profound sophistication of its role as a neuromodulator.

Non-Genomic Signaling the Rapid Response System

The classical model of steroid hormone action involves the hormone binding to an intracellular receptor, which then translocates to the cell nucleus to act as a transcription factor, altering gene expression over hours or days. While this genomic pathway is important, many of estrogen’s effects on cognition occur far too rapidly to be explained by this mechanism alone.

These rapid effects are attributed to non-genomic signaling, initiated by estrogen binding to receptors located within or near the neuronal membrane, including membrane-associated ERα and ERβ, and GPER1. This binding can trigger intracellular signaling cascades within seconds to minutes, leading to immediate changes in neuronal excitability and synaptic function.

The Estrogen and Glutamate Receptor Partnership

One of the most critical non-genomic mechanisms involves a direct interaction between estrogen receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), particularly mGluR1a. Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, and its action at synapses is the foundation of learning and memory processes like Long-Term Potentiation (LTP).

Research has shown that ERα and ERβ can form a physical complex with mGluR1a at the neuronal membrane. When estradiol binds to its receptor in this complex, it potentiates the signaling of the mGluR, effectively amplifying the neuron’s response to glutamate. This rapid, synergistic action is a cornerstone of how E2 enhances synaptic plasticity. It primes the synapse to be more responsive to incoming signals, making it easier for LTP to be induced and for memories to be encoded.

Estrogen can rapidly amplify the brain’s primary learning signals at the molecular level.

The ERK/MAPK Pathway a Cascade for Synaptic Growth

The activation of the ER-mGluR complex initiates a series of intracellular events, most notably the activation of the Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK) pathway, which is part of the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) family of signaling cascades. This pathway functions as a molecular relay system, carrying the signal from the cell membrane down to the nucleus and out to the dendrites to orchestrate the construction of new synapses. The steps in this cascade are precise and sequential.

The table below outlines this critical signaling pathway, demonstrating the steps from the initial hormonal signal to the tangible outcome of enhanced cognitive architecture.

| Step | Molecular Event | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initiation | Estradiol (E2) binds to membrane-associated ERα/ERβ, which is complexed with mGluR1a. | Activates the receptor complex, preparing it to transduce a signal. |

| 2. Kinase Activation | The activated complex triggers a series of phosphorylation events, leading to the activation of the ERK/MAPK cascade. | The signal is amplified and transmitted from the membrane into the cell’s cytoplasm. |

| 3. CREB Phosphorylation | Activated ERK translocates to the nucleus and phosphorylates the transcription factor CREB (cAMP Response Element-Binding protein). | Phosphorylated CREB becomes an active transcription factor, capable of turning on specific genes. |

| 4. Gene Transcription | Active CREB binds to the DNA and initiates the transcription of genes essential for synaptic plasticity, such as Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). | The cell begins to manufacture the proteins required for building and strengthening synapses. |

| 5. Local Protein Synthesis | The signal also activates other pathways like the mTOR pathway, which promotes the local translation of proteins in the dendrites, close to the synapse. | Structural proteins are synthesized on-site, allowing for rapid modification and growth of dendritic spines. |

| 6. Synaptogenesis | The newly synthesized proteins, including those from BDNF signaling, are used to construct new dendritic spines and strengthen existing ones. | The physical architecture of the neural network is modified, leading to enhanced memory formation and cognitive capacity. |

How Does Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Amplify the Effect?

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) is a protein that is often described as “Miracle-Gro for the brain.” It is a master regulator of neuronal survival, growth, and synaptic plasticity. The relationship between estrogen and BDNF is synergistic and bidirectional.

As noted, one of the key outcomes of the E2-initiated ERK/MAPK cascade is the increased transcription of the BDNF gene. The resulting increase in BDNF protein then acts on its own set of receptors (TrkB receptors) to further promote synaptogenesis and enhance neuronal function.

In essence, estrogen starts a process that leads to more BDNF, and BDNF then amplifies the very processes that estrogen initiated. This positive feedback loop is a powerful mechanism for maintaining a healthy, plastic, and cognitively resilient brain. The decline of estrogen during menopause disrupts this vital partnership, leading to lower levels of BDNF and contributing to the age-associated decline in synaptic plasticity.

Why Is the Timing of Hormonal Therapy so Important?

The “critical window” hypothesis for hormone therapy can be understood through this molecular lens. The intricate signaling machinery, including the density and sensitivity of estrogen receptors and their coupling with mGluRs, is itself dependent on a consistent estrogenic environment. Prolonged estrogen deprivation, as seen in the years following menopause, can lead to a downregulation of this machinery.

The receptors may become less numerous or less responsive. Consequently, reintroducing estrogen later in life may fail to elicit the same robust activation of the ERK/MAPK and BDNF pathways. The system has been offline for too long to be easily rebooted. This provides a compelling molecular rationale for considering hormonal support earlier in the menopausal transition, when the brain’s signaling architecture is still intact and responsive.

The following factors are critical in determining the neurobiological response to hormonal interventions:

- Receptor Availability ∞ The density and subtype (ERα vs. ERβ) of estrogen receptors in key brain regions like the hippocampus can change with age and hormonal status.

- Signaling Pathway Integrity ∞ The efficiency of downstream cascades like ERK/MAPK can be compromised by age-related cellular changes or chronic inflammation.

- Formulation and Route of Administration ∞ Different types of estrogens (e.g. conjugated equine estrogens vs. bioidentical estradiol) and routes of delivery (oral vs. transdermal) can have different metabolic fates and impacts on the brain.

- Genetic Factors ∞ Individual genetic variations, such as in the gene for apolipoprotein E (APOE), can modulate the brain’s response to both estrogen and the risk for neurodegenerative conditions.

In conclusion, the influence of estrogen on cognition is a testament to the exquisite complexity of human neurobiology. Its role transcends simple hormonal messaging, extending into the core molecular processes that govern how our brains learn, adapt, and remember. By acting as a rapid-response modulator of synaptic plasticity through non-genomic signaling pathways, estrogen establishes itself as an indispensable element for maintaining cognitive vitality throughout the lifespan.

References

- Brann, Darrell W. et al. “Estrogen and Cognitive Function.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 93, no. 11_supplement_1, 2008, pp. S54-S58.

- Henderson, Victor W. “Estrogen-Containing Hormone Therapy and Women’s Cognitive Health ∞ Clarity, Confusion, and Opportunity.” JAMA, vol. 314, no. 20, 2015, pp. 2131-2133.

- McEwen, Bruce S. and Tiernan T. Murphy. “The End of the Menstrual Cycle ∞ The Neurobiology of Perimenopause.” Science, vol. 373, no. 6554, 2021, pp. 481-482.

- Spencer, J. L. et al. “Estrogen action in the brain ∞ mechanisms and neuroprotective effects.” Neuroscience Letters, vol. 466, no. 2, 2009, pp. 73-77.

- Frick, Karyn M. “Molecular mechanisms underlying the memory-enhancing effects of estradiol.” Hormones and Behavior, vol. 74, 2015, pp. 119-130.

- Hara, Y. et al. “Estrogen effects on cognitive and synaptic health over the lifecourse.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 95, no. 3, 2015, pp. 785-807.

- Gleason, Carey E. et al. “Effects of Hormone Therapy on Cognition and Mood in Recently Postmenopausal Women ∞ Findings from the Randomized, Controlled KEEPS-Cognitive and Affective Study.” PLoS Medicine, vol. 12, no. 6, 2015, e1001833.

- Sherwin, Barbara B. “Estrogen and Cognitive Functioning in Women.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 24, no. 2, 2003, pp. 133-151.

- Rudick, C. N. and C. S. Woolley. “Estradiol induces a rapid, reversible increase in dendritic spine density in the rat hippocampus.” Brain Research, vol. 838, no. 1-2, 1999, pp. 113-118.

- Luine, V. N. “Estradiol increases choline acetyltransferase activity in specific basal forebrain nuclei and projection areas of female rats.” Experimental Neurology, vol. 89, no. 2, 1985, pp. 484-490.

Reflection

The journey into the science of your own body is a profound one. The information presented here provides a detailed blueprint, connecting the subjective feelings of cognitive fog or mood instability to the objective, elegant machinery of your neurobiology.

This knowledge serves a distinct purpose ∞ to replace confusion with clarity and to validate your personal experience with concrete, evidence-based explanations. It confirms that what you feel is real, rooted in the intricate interplay of hormones and neurotransmitters that define your internal world.

This understanding is the essential first step. It shifts the perspective from one of passive endurance to one of active inquiry. The biological systems described are not static; they are dynamic and responsive. The path forward involves asking deeper questions, not just about the science, but about yourself. How do these systems manifest in your unique life? What does optimal function feel like for you? The answers will shape your personal health narrative.

Consider this knowledge a map. A map is a powerful tool, but it only becomes useful when you decide on a destination and begin to navigate the terrain. The next phase of your journey is about translating this biological understanding into a personalized strategy.

It involves looking at your own life, your own symptoms, and your own goals, and seeking guidance to create a path that restores balance and reclaims the vitality that is your biological birthright. The potential for recalibration and optimization resides within your own systems, waiting to be accessed with informed and intentional action.