Fundamentals

You may feel it as a persistent, deep-seated fatigue that coffee no longer touches. It could manifest as a fog that clouds your thoughts, a frustrating inability to lose weight despite your best efforts, or a general sense of being unwell that defies simple explanation.

These experiences are valid, and they are often the first signals of a profound communication breakdown within your body’s most critical regulatory systems. Your journey to understanding this begins with appreciating the deep, biological conversation constantly occurring between your gut and your thyroid gland. This connection is a central pillar of your metabolic health, dictating your energy, mood, and overall vitality.

Think of your thyroid gland, a small, butterfly-shaped organ at the base of your neck, as the master thermostat for your body’s metabolism. It produces hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), that travel to every cell, instructing them on how fast to work, how much energy to burn, and how to grow and repair.

When this system is functioning optimally, you feel energetic, clear-headed, and resilient. The instructions are sent and received without interference, maintaining a state of dynamic equilibrium. This entire process, however, is exquisitely sensitive to inputs from another major biological system ∞ your gut.

The Gut a Dynamic Frontier

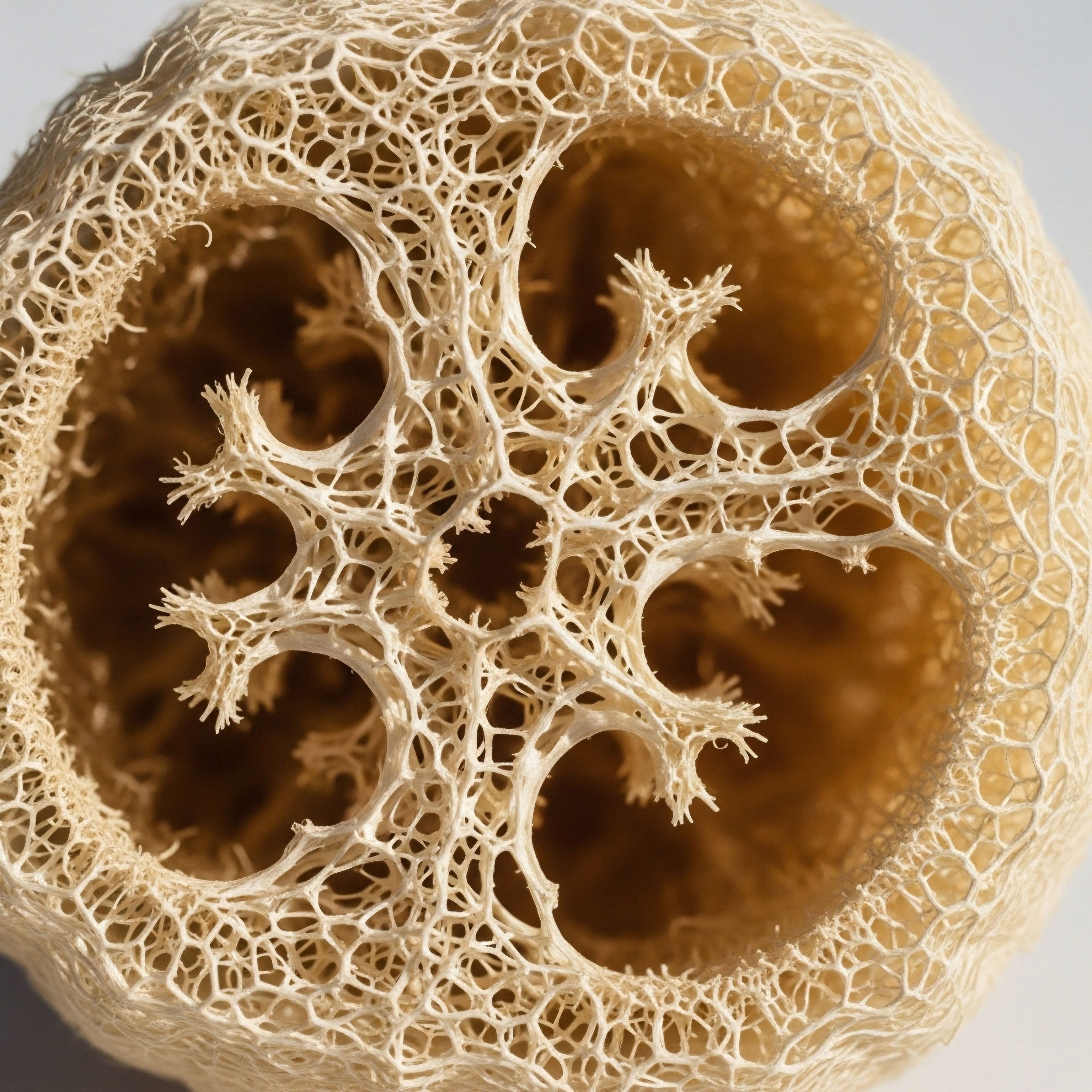

Your gastrointestinal tract is far more than a simple tube for digesting food. It is a complex and intelligent frontier, home to a teeming ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms known as the gut microbiome. This internal garden plays a foundational role in your health.

It synthesizes essential vitamins, helps you digest nutrients your own body cannot, and, most critically, educates and calibrates your immune system. The physical lining of your intestines acts as a highly selective barrier, a sophisticated security checkpoint designed to absorb vital nutrients while preventing harmful substances from entering your bloodstream.

A healthy gut barrier is resilient and tightly regulated. It maintains a delicate balance, allowing passage for the building blocks of health while standing firm against potential threats. This integrity is the bedrock of a stable immune system and a properly functioning endocrine network.

The conversation between the gut and the thyroid depends on the reliability of this barrier. The thyroid requires a steady supply of specific micronutrients absorbed through the gut, and it relies on the gut to maintain a calm, non-inflammatory immune environment to function without being targeted for attack.

The integrity of the intestinal barrier is a direct determinant of systemic inflammation and thyroid health.

When the Conversation Breaks Down

Environmental toxins introduce static and interference into this finely tuned biological dialogue. These substances, which include heavy metals from industrial pollution, chemicals in plastics like Bisphenol A (BPA), and pesticides on our food, act as systemic disruptors. One of their primary targets is the delicate lining of the gut. They can degrade the tight junctions between intestinal cells, effectively creating gaps in the security barrier. This condition is known as increased intestinal permeability, or “leaky gut.”

When the gut barrier is compromised, substances that should remain contained within the digestive tract gain unauthorized access to the bloodstream. These can include undigested food proteins, microbial fragments, and the very environmental toxins that caused the damage in the first place.

Your immune system, which is largely stationed just behind the gut wall, identifies these newcomers as foreign invaders. It mounts a powerful and sustained inflammatory response. This systemic inflammation is the starting point of a cascade of issues that directly impact the thyroid gland, turning a localized gut problem into a body-wide state of dysfunction and distress.

Intermediate

Understanding that toxins disrupt the gut-thyroid axis is the first step. The next layer of comprehension involves examining the specific mechanisms through which this disruption occurs. The biochemical processes are precise, and the damage is not random. Environmental toxins leverage specific biological pathways to compromise gut integrity and directly interfere with thyroid function, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation and hormonal dysregulation.

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals a Closer Look

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) are a class of exogenous compounds that interfere with the normal function of the body’s hormonal systems. They can achieve this by mimicking the structure of natural hormones, blocking hormone receptors, or altering the way hormones are produced, transported, and metabolized. Many EDCs have a profound impact on both the gut microbiome and the thyroid gland simultaneously.

The Case of BPA and Phthalates

Bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates are industrial chemicals used to make plastics and resins, found in everything from food containers to personal care products. Studies show that these chemicals can alter the composition of the gut microbiome, favoring the growth of inflammatory bacteria while reducing beneficial species.

This shift, known as dysbiosis, contributes to the breakdown of the intestinal barrier. Simultaneously, these chemicals can directly impact the thyroid. BPA, for example, has been shown to interfere with thyroid hormone receptors and inhibit the enzyme responsible for converting the inactive thyroid hormone T4 into the active form T3, leading to symptoms of hypothyroidism even when T4 levels appear normal.

The Heavy Metal Burden

Heavy metals such as mercury, lead, and cadmium represent another significant toxic threat. These elements can accumulate in the body over time, exerting their damaging effects on multiple organ systems. The thyroid gland is particularly vulnerable. Because of its need for iodine to produce hormones, the thyroid has a robust system for absorbing iodine from the bloodstream.

Unfortunately, heavy metals like mercury and other compounds like perchlorate from industrial waste are structurally similar enough to iodine that the thyroid can absorb them by mistake. This competitive inhibition means the thyroid becomes starved of its essential building block while accumulating toxic substances.

Cadmium has been shown to directly disrupt thyroid hormone secretion and impair the conversion of T4 to T3. This toxic accumulation generates significant oxidative stress within the gland, damaging thyroid cells and marking them for potential autoimmune attack.

The Immune System Caught in the Crossfire

When the gut barrier is compromised by toxins, the immune system is forced into a state of high alert. Two key mechanisms explain how this localized gut issue translates into a targeted attack on the thyroid.

One of the most potent inflammatory triggers originating from the gut is Lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS is a component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, which are a normal part of the gut microbiome. In a healthy gut, LPS remains safely contained.

With increased intestinal permeability, LPS leaks into the bloodstream, a condition called metabolic endotoxemia. The immune system recognizes LPS as a sign of a severe bacterial invasion and launches a powerful, body-wide inflammatory response. Thyroid cells have receptors that can be directly activated by circulating LPS, triggering inflammation within the gland itself and contributing to the development of thyroid disorders.

A second, more insidious mechanism is molecular mimicry. The immune system works by recognizing specific protein shapes. Some environmental triggers and the gut bacteria that flourish in a dysbiotic environment possess proteins that look remarkably similar to proteins found on human thyroid cells, such as thyroid peroxidase (TPO) or thyroglobulin.

The immune system, in its effort to neutralize the foreign invader, creates antibodies that unfortunately also recognize and attack the body’s own thyroid tissue. This case of mistaken identity is a primary driver of autoimmune thyroid conditions like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease.

Systemic inflammation originating from a compromised gut barrier is a primary driver of autoimmune thyroid disease.

What Are the Clinical Implications for Diagnosis?

The overlapping symptoms of gut dysfunction and thyroid disorders can make diagnosis challenging without a comprehensive approach. A person may present with fatigue, depression, and constipation, which could be attributed solely to hypothyroidism. A conventional approach might involve prescribing thyroid hormone replacement.

While this may provide some relief, it fails to address the underlying gut inflammation and toxic burden that may be driving the condition. The ongoing immune assault and poor nutrient absorption will persist, limiting the effectiveness of the therapy and preventing a full return to wellness. This highlights the necessity of viewing the body as an interconnected system.

The following table illustrates the significant overlap in symptoms, underscoring the importance of investigating both systems when either is suspected of dysfunction.

| Symptom | Commonly Associated with Hypothyroidism | Commonly Associated with Gut Dysbiosis |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue and Low Energy | ✔ | ✔ |

| Brain Fog / Poor Concentration | ✔ | ✔ |

| Depression and Mood Swings | ✔ | ✔ |

| Constipation | ✔ | ✔ |

| Weight Gain or Inability to Lose Weight | ✔ | ✔ |

| Skin Issues (Dry Skin, Eczema, Acne) | ✔ | ✔ |

| Joint and Muscle Pain | ✔ | ✔ |

Recognizing the sources of these disruptive chemicals is a practical step toward mitigating their effects. Many are ubiquitous in modern life, yet conscious choices can reduce exposure.

- Plastics ∞ BPA and phthalates are found in hard plastic containers, the lining of canned foods, and many soft plastics. Opting for glass, stainless steel, or BPA-free plastics is a prudent measure.

- Pesticides ∞ Organophosphate pesticides used in industrial agriculture are known endocrine disruptors. Choosing organic produce when possible can lower this exposure.

- Heavy Metals ∞ Mercury is prevalent in large predatory fish like tuna and swordfish and in dental amalgams. Cadmium can be found in cigarette smoke and some industrial emissions. Lead can leach from old paint and pipes.

- Water Contaminants ∞ Industrial runoff can introduce perchlorate and nitrates into the water supply, both of which interfere with iodine uptake in the thyroid. Using a high-quality water filter is an essential defensive strategy.

Academic

A systems-biology perspective reveals the gut-thyroid connection as a complex network of signaling pathways involving the microbiome, the intestinal epithelial barrier, the immune system, and the endocrine apparatus. Environmental toxins act as pathogenic inputs that disrupt the network’s homeostasis at a cellular and molecular level. The progression from toxin exposure to clinical thyroid disease involves specific immunological and metabolic derangements that are now being characterized with increasing precision.

The Cellular Mechanisms of Toxin-Induced Thyroid Autoimmunity

The development of autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD), such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, is fundamentally a loss of immune tolerance. Environmental toxins and the resulting gut dysbiosis are potent drivers of this process by skewing the differentiation of T helper cells. A healthy immune system maintains a balance between pro-inflammatory T helper 17 (Th17) cells and anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells (Tregs).

Gut dysbiosis, particularly a decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria, starves the Tregs of their primary energy source. This deficit, combined with the inflammatory signals from toxins and LPS, promotes the dominance of the Th17 lineage. These Th17 cells produce cytokines like IL-17 and IL-22, which promote inflammation, further degrade the gut barrier, and are directly implicated in the destructive infiltration of immune cells into the thyroid gland.

At the molecular level, the interaction between gut-derived LPS and thyroid cells is mediated by Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs), specifically TLR4. When circulating LPS binds to TLR4 on thyrocytes, it initiates an intracellular signaling cascade involving NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells).

This transcription factor upregulates the expression of numerous pro-inflammatory genes, including those for cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules. This process effectively turns the thyroid gland into an active participant in its own inflammatory destruction, creating a localized environment that attracts more immune cells and perpetuates the autoimmune attack.

How Does This Affect Hormonal Optimization Protocols?

This deep understanding has profound implications for clinical practice, particularly for hormonal optimization protocols. Administering exogenous hormones, whether it is Testosterone Cypionate for a male with andropause or Levothyroxine for a patient with hypothyroidism, into an unaddressed inflammatory environment is a suboptimal strategy. The efficacy of any hormonal therapy depends on several factors that are directly compromised by the gut-derived inflammation we have discussed.

- Absorption ∞ Systemic inflammation originating in the gut can impair the absorption of oral medications, including thyroid hormones and supplements like selenium and zinc that are critical for thyroid function.

- Hormone Conversion ∞ The conversion of inactive T4 to the biologically active T3 is primarily carried out by deiodinase enzymes. These enzymes are selenium-dependent and are highly sensitive to oxidative stress and inflammation. High levels of inflammatory cytokines can suppress deiodinase activity, leading to a state of functional hypothyroidism at the cellular level, even if serum T4 and TSH levels are within the normal range.

- Receptor Sensitivity ∞ Chronic inflammation can also lead to hormone receptor resistance. Cells downregulate their receptors in response to the inflammatory storm, becoming less sensitive to the hormonal signals they receive. This means that even with adequate hormone levels in the blood, the message is not being received effectively at the tissue level.

Therefore, a truly effective wellness protocol must address the root cause. Before or alongside initiating hormonal replacement, a clinician must investigate and manage the patient’s gut health and toxicant exposure. This involves advanced diagnostic testing to quantify the extent of the damage, such as measuring serum zonulin as a marker for intestinal permeability, conducting comprehensive stool analysis to assess the microbiome, and utilizing urine or blood tests to screen for heavy metals and other environmental toxins.

Effective hormonal therapy requires a foundation of gut health and minimal systemic inflammation.

Micronutrient Metabolism the Overlooked Connection

The gut microbiome’s role extends to the metabolism and bioavailability of micronutrients that are indispensable for thyroid health. Selenium, zinc, and iodine are not simply absorbed; their journey into the body is mediated by gut bacteria. Selenium is a critical component of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase and the deiodinase enzymes.

Gut dysbiosis can sequester selenium, limiting its availability for the host. A deficiency in selenium directly impairs the body’s ability to convert T4 to T3 and protect the thyroid gland from the oxidative stress generated during hormone production. Zinc is also required for T3 production and helps T3 bind to its receptors within the cell nucleus.

Toxin-driven gut inflammation impairs the absorption of these essential minerals, creating critical deficiencies that cripple thyroid function from multiple angles. This transforms the problem from a simple hormone deficiency into a complex metabolic impairment rooted in gut health.

The following table provides a summary of key environmental toxins and their specific, evidence-based impacts on the gut-thyroid axis.

| Toxin/Chemical | Primary Sources | Mechanism of Action on Gut-Thyroid Axis | Associated Thyroid Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury (Hg) | Dental amalgams, large predatory fish, industrial pollution | Competitively inhibits iodine uptake by the thyroid; generates high oxidative stress; damages thyroid cells, triggering autoimmunity. | Hypothyroidism, Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Plastic containers, canned food linings, thermal paper receipts | Increases intestinal permeability; alters gut microbiome composition; blocks thyroid hormone receptors. | Thyroid Hormone Resistance, Hypothyroidism |

| Perchlorate | Industrial waste, rocket fuel, contaminated water/food | Potently blocks the sodium-iodide symporter (NIS), preventing iodine from entering the thyroid gland. | Goiter, Hypothyroidism |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Cigarette smoke, industrial emissions, contaminated shellfish | Disrupts thyroid hormone secretion; interferes with T4-to-T3 conversion; accumulates in the thyroid, causing damage. | Hypothyroidism, Thyroid Nodules |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Gut-derived from gram-negative bacteria | Enters circulation via a permeable gut; binds to TLR4 on thyrocytes, inducing a direct inflammatory response within the gland. | Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, Graves’ Disease |

References

- Knezevic, J. et al. “Thyroid-Gut-Axis ∞ How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function?” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 6, 2020, p. 1769.

- Fröhlich, Eleonore, and Richard Wahl. “Microbiota and Thyroid Interaction in Health and Disease.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 30, no. 8, 2019, pp. 479-490.

- Ghareghani, M. et al. “The role of gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroiditis.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 549, 2022, p. 111640.

- Myers, Amy. “The Toxin, Heavy Metal & Thyroid Connection.” Amy Myers MD, 31 July 2015, updated 22 July 2025.

- Ralli, M. et al. “The impact of environmental factors and contaminants on thyroid function and disease from fetal to adult life ∞ current evidence and future directions.” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 46, no. 12, 2023, pp. 2533-2554.

- Chen, Y. et al. “Association Between Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Thyroid Disease ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 12, 2021, p. 774362.

- Benvenga, S. et al. “Endocrine Disruptors and Thyroid Autoimmunity.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 34, no. 1, 2020, p. 101377.

- Virili, C. et al. “Gut microbiota and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.” Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 19, no. 4, 2018, pp. 293-300.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map, a detailed biological chart connecting your internal experiences to complex physiological processes. It traces the pathways from the external environment, through the critical gateway of your gut, to the master regulator of your metabolism, the thyroid.

This knowledge shifts the perspective on symptoms from a collection of isolated problems to the coherent language of a body under stress. The fatigue, the brain fog, the metabolic resistance ∞ these are signals, messages from an intelligent system communicating a state of imbalance.

Understanding these intricate connections is the foundational step. The next is to ask what this means for your unique biology. What is the specific conversation your body is trying to have? Which signals are the loudest? Recognizing that your vitality is deeply interwoven with the health of your internal ecosystem provides you with a new lens through which to view your health journey.

It transforms you from a passive recipient of symptoms into an active, informed participant in your own wellness. This journey is about more than just addressing a single lab value; it is about restoring the integrity of the entire system to allow your body to function with the clarity and energy that is its birthright.