Fundamentals

You may have noticed a persistent, low-grade friction in your own biology. It can manifest as a subtle fatigue that sleep does not resolve, a frustrating difficulty in managing your weight, or a general sense that your body is not functioning with the vitality it once had.

This experience is valid, and it points toward a complex interaction between your internal systems and the world around you. Your body’s intricate hormonal network, the endocrine system, is a finely tuned communication grid responsible for regulating everything from your metabolism and mood to your reproductive health and stress response. This system is designed to be resilient, yet it is also exquisitely sensitive to external signals, including a class of synthetic chemicals known as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs).

These compounds are pervasive in modern life, found in everything from plastics and food packaging to cosmetics and pesticides. They represent a persistent, low-dose challenge to your body’s internal equilibrium. EDCs introduce confusing messages into your biological command centers.

Their chemical structures can be similar enough to your own hormones, such as estrogen or testosterone, that they can interfere with the normal signaling processes that govern your health. This interference is the central mechanism by which environmental factors can influence your endocrine function and hormonal balance.

Understanding the Body’s Messaging Service

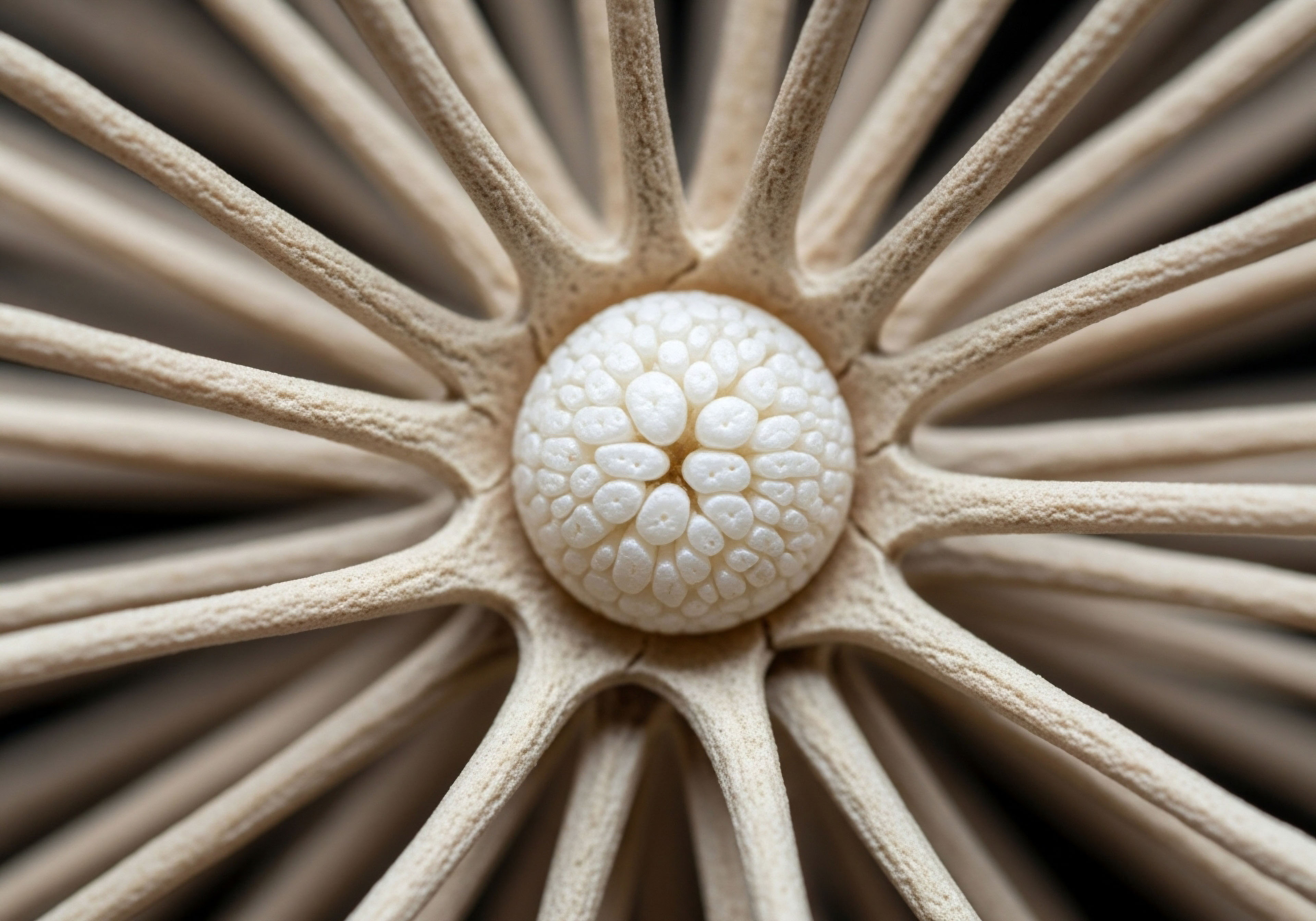

Think of your endocrine system as a sophisticated postal service. The glands, like the thyroid, adrenals, and gonads, are the post offices that dispatch chemical messengers called hormones. These hormones travel through the bloodstream to specific destinations ∞ target cells throughout your body.

Each target cell has a receptor, which acts like a specific mailbox, designed to receive a particular hormone. When a hormone docks with its receptor, it delivers a precise instruction, such as “increase metabolism,” “build muscle,” or “release stored energy.” This system relies on clear communication and precise delivery for the body to function optimally.

EDCs disrupt this service in several fundamental ways. They can act as impostors, mimicking your natural hormones and delivering incorrect messages. They might also block the mailboxes, preventing your real hormones from delivering their instructions. Some EDCs can even interfere with the production, transport, or breakdown of your natural hormones, effectively disrupting the entire postal route from start to finish. The result is a system filled with static and crossed signals, which can manifest as the symptoms you experience.

What Are the Primary Sources of Exposure?

Recognizing the sources of these chemicals is the first step in understanding their influence. While it is impossible to avoid them completely, awareness can inform your choices and reduce your overall biological burden. The ubiquity of these compounds means that human exposure occurs daily through ingestion, inhalation, and skin contact.

- Bisphenols (like BPA) ∞ Commonly found in polycarbonate plastics (hard, clear plastics) and the linings of food and beverage cans. Exposure is primarily through diet.

- Phthalates ∞ Used to make plastics more flexible and durable. They are present in vinyl flooring, food packaging, and many personal care products like lotions, shampoos, and cosmetics, where they help retain scents and textures.

- Pesticides and Herbicides ∞ Agricultural chemicals used on crops can remain on produce and find their way into the water supply. Certain types are known to interfere with both male and female reproductive hormones as well as thyroid function.

- Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) ∞ A large group of chemicals used to make surfaces resistant to stains, grease, and water. They are found in non-stick cookware, waterproof clothing, and food packaging.

The cumulative effect of these low-dose exposures over a lifetime presents a significant variable in your personal health equation. It is a variable that was not present for previous generations and one that modern clinical science is actively working to understand and address. This environmental load can strain your hormonal systems, potentially contributing to the very conditions, such as low testosterone or menopausal symptoms, that lead individuals to seek personalized wellness protocols.

The endocrine system is the body’s sensitive communication network, and environmental chemicals can act as static, disrupting its vital messages.

This understanding shifts the perspective on symptoms. Instead of viewing fatigue or metabolic struggles as isolated personal failings, we can see them as potential consequences of a biological system under duress. Your lived experience is a critical piece of data, pointing toward an imbalance that can be investigated and understood through a clinical lens.

The goal is to identify the sources of the disruption and provide the targeted support your body needs to clear the static and restore its own clear, powerful communication.

Intermediate

To appreciate how environmental factors translate into tangible symptoms, we must examine the specific biological mechanisms at play. The influence of endocrine-disrupting chemicals extends beyond simple mimicry; these compounds can alter the very synthesis, transport, and metabolism of the hormones that govern your physiology.

This biochemical interference is directly relevant to the conditions addressed by targeted clinical protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for men and women or therapies designed to support thyroid function. Understanding these pathways clarifies why restoring hormonal balance often requires a multi-faceted approach that accounts for this environmental pressure.

Mechanisms of Hormonal Disruption

EDCs operate through several distinct molecular pathways. Their ability to cause harm is not always related to the dose, as even very low levels of exposure can have significant effects, particularly during sensitive developmental windows. The primary mechanisms create a cascade of downstream consequences for your metabolic and reproductive health.

A key target for many EDCs is the family of nuclear receptors. These are the “mailboxes” inside your cells that hormones bind to in order to activate genetic instructions. For example:

- Agonistic Action ∞ Some EDCs, like certain xenoestrogens found in plastics, bind to estrogen receptors and activate them. This can lead to an excessive estrogenic signal in the body, a state that, in men, can contribute to lower testosterone efficacy and increased fat storage. For this reason, protocols for men on TRT often include an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole, which is designed to block the conversion of testosterone into estrogen and mitigate these effects.

- Antagonistic Action ∞ Other EDCs can bind to a receptor without activating it, effectively blocking the natural hormone from docking. Certain fungicides have been shown to block the androgen receptor, preventing testosterone from exerting its effects on muscle and bone maintenance, libido, and cognitive function. This can produce symptoms of low testosterone even when blood levels of the hormone appear normal.

- Altered Steroidogenesis ∞ Many EDCs interfere directly with the enzymes responsible for creating hormones. The entire process of converting cholesterol into hormones like testosterone, DHEA, and estradiol is called steroidogenesis. Phthalates, for instance, have been shown in studies to inhibit the activity of key enzymes in this pathway within the testes, potentially leading to reduced testosterone production. This provides a clear rationale for protocols that aim to stimulate the body’s own production machinery, such as using Gonadorelin to support the signaling cascade that begins in the brain.

How Does the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis Respond?

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis is the central command-and-control system for reproductive health in both men and women. The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones, in turn, signal the gonads (testes or ovaries) to produce testosterone or estrogen. This entire system operates on a sensitive negative feedback loop; when hormone levels are sufficient, the signal from the hypothalamus is dampened.

EDCs can disrupt this delicate feedback system. For example, by mimicking estrogen, a chemical like Bisphenol A (BPA) can trick the hypothalamus into thinking there are already high levels of sex hormones in circulation. This can cause the hypothalamus to reduce its GnRH signal, leading to lower LH and FSH output from the pituitary, and consequently, decreased natural testosterone production in the testes.

This is a foundational reason why men may experience symptoms of low testosterone and why therapies often focus on restoring the integrity of this entire axis, not just replacing the end-product hormone.

Environmental chemicals can directly sabotage the body’s hormone production lines and interfere with the central feedback loops that maintain balance.

The table below outlines some common EDCs and their documented effects on hormonal pathways, connecting them to symptoms and the rationale behind specific clinical interventions.

| Endocrine Disruptor | Common Sources | Primary Mechanism of Action | Associated Symptoms & Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Plastics, can linings, thermal paper receipts |

Estrogen receptor agonist; may interfere with thyroid receptors and the HPG axis feedback loop. |

Can contribute to symptoms of estrogen dominance. In men, this may manifest as reduced libido and increased adiposity. This validates the use of estrogen-blocking agents like Anastrozole in some TRT protocols. |

| Phthalates | Personal care products, vinyl, food packaging |

Inhibit enzymes in the testosterone synthesis pathway (steroidogenesis); can act as androgen receptor antagonists. |

Directly linked to lower testosterone levels and reduced sperm quality. This underscores the need for therapies that support the HPG axis, such as Gonadorelin or Enclomiphene, to stimulate natural production. |

| Triclosan | Antibacterial soaps, some toothpastes |

Reduces thyroid hormone levels by interfering with synthesis and transport. |

Can contribute to subclinical hypothyroidism, with symptoms like fatigue, cold intolerance, and metabolic slowdown. Highlights the importance of comprehensive thyroid testing beyond just TSH. |

| Atrazine | Herbicide, common water contaminant |

Induces aromatase, the enzyme that converts testosterone to estrogen. |

Can significantly alter the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio, leading to hormonal imbalance in both sexes. This reinforces the clinical strategy of managing estrogen levels as part of a comprehensive hormonal optimization plan. |

This deeper understanding of mechanism allows for a more precise clinical approach. When a patient presents with symptoms of hormonal imbalance, a clinician informed by this science recognizes that the solution may involve more than simple hormone replacement. It may require protocols that actively counteract the specific disruptions caused by environmental exposures, such as blocking excess estrogen conversion or directly stimulating the body’s suppressed production pathways.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of endocrine disruption moves beyond the one-chemical, one-receptor model and into the domain of systems biology. The physiological impact of environmental EDCs is a function of cumulative exposure to complex mixtures, the timing of that exposure, and the subsequent epigenetic modifications that can alter hormonal sensitivity for years.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis serves as a particularly illustrative case study for this complex interplay. Its regulation is foundational to reproductive health, and its perturbation by xenobiotics provides a clear molecular basis for the symptoms that drive individuals to seek advanced hormonal therapies, including TRT and fertility-stimulating protocols.

Epigenetic Reprogramming of the HPG Axis

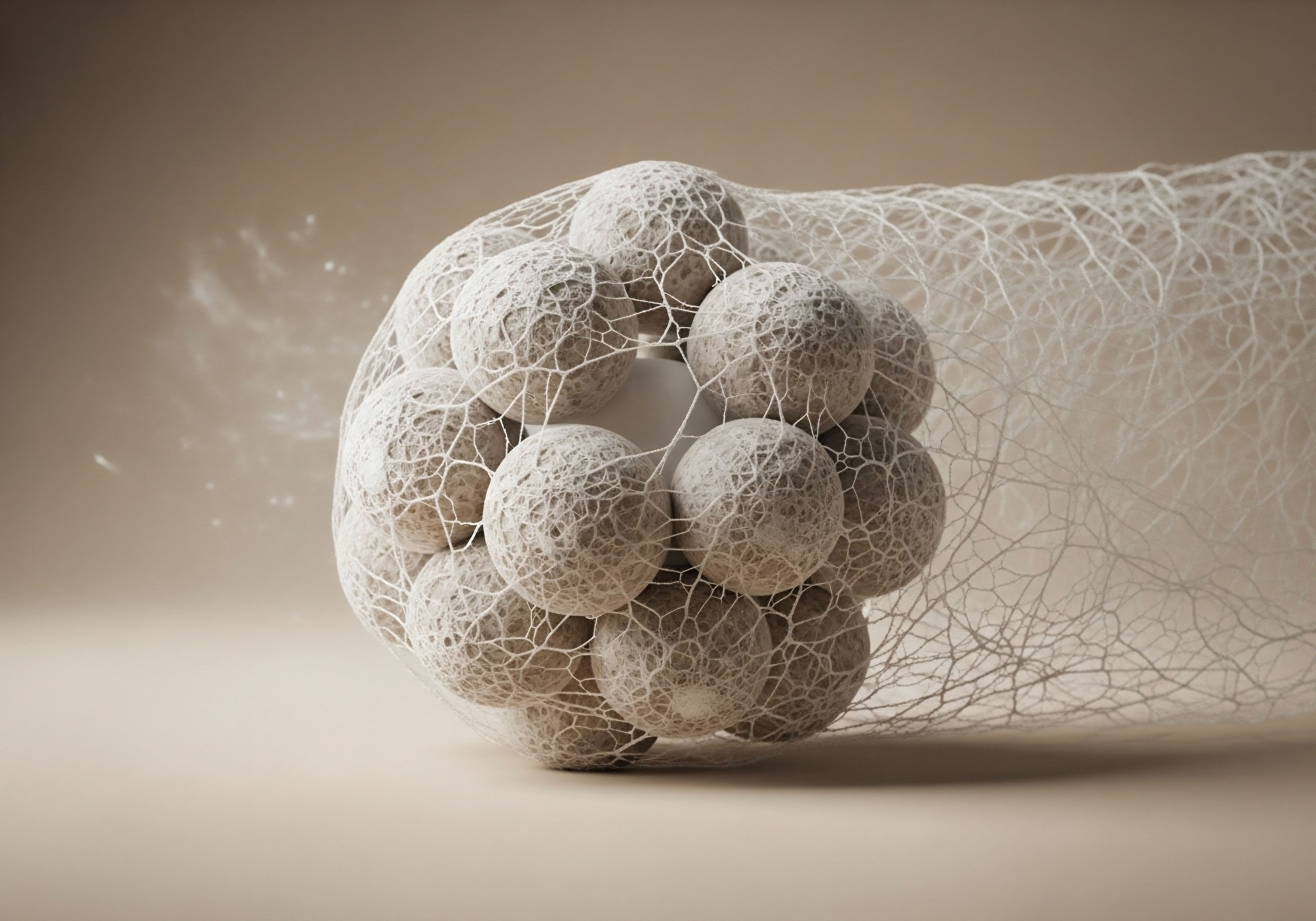

The concept of epigenetics is central to understanding the long-term consequences of EDC exposure, especially during critical developmental windows like fetal life and puberty. Epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation and histone modification, are chemical tags that attach to DNA and regulate gene expression without altering the underlying genetic code.

They act as a set of instructions, telling genes when to turn on or off. EDCs have been demonstrated to alter these epigenetic patterns, leading to a persistent “memory” of the exposure that can reprogram hormonal function.

For instance, studies have shown that prenatal exposure to chemicals like vinclozolin (a fungicide) or BPA can alter the DNA methylation patterns of genes in the hypothalamus that are critical for GnRH neuron development and function. This can permanently change the setpoint for the entire HPG axis, leading to conditions like hypogonadism or premature reproductive senescence in adulthood.

This phenomenon explains why an individual with no genetic predisposition may develop hormonal deficiencies. Their system was, in effect, programmed for dysfunction by an early environmental insult. This provides a compelling rationale for interventions that can directly stimulate components of the axis, such as using Gonadorelin (a GnRH analogue) to bypass a potentially suppressed hypothalamic signal and directly activate the pituitary.

Non-Monotonic Dose Responses a Clinical Challenge

Traditional toxicology operated on the principle that “the dose makes the poison,” implying a linear relationship where higher exposures lead to greater harm. Research into EDCs has fundamentally challenged this assumption, revealing the prevalence of non-monotonic dose-response curves. In this model, low doses of a chemical can sometimes exert more potent biological effects than higher doses. This is particularly true for hormone-mimicking compounds, as the endocrine system is designed to respond to minute concentrations of hormones.

A high dose of an EDC might saturate and then downregulate cellular receptors, leading to a muted response. A very low, environmentally relevant dose, however, can activate those same receptors without triggering the cell’s protective downregulation mechanisms, leading to a sustained, disruptive signal. This reality complicates regulatory efforts and clinical diagnosis.

Standard toxicology screenings may miss the effects of low-dose mixtures. It also means that a patient’s total environmental burden, composed of dozens of chemicals at low concentrations, could create a significant synergistic effect that is not captured by measuring any single compound.

This reinforces the clinical approach of treating the patient’s symptoms and biomarker profile, using therapies like TRT to restore physiological balance in a system that is being actively perturbed by a complex and difficult-to-quantify environmental load.

The long-term impact of environmental endocrine disruptors is encoded through epigenetic changes that can alter hormonal function across a lifetime.

The table below details the specific points of vulnerability within the HPG axis and the corresponding clinical interventions designed to address them. This illustrates a systems-based approach to restoring function.

| Axis Component | Vulnerability to EDCs | Biochemical Consequence | Targeted Clinical Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamus |

EDCs can alter the epigenetic programming of GnRH neurons and disrupt neurotransmitter inputs (e.g. Kisspeptin signaling). |

Suppressed or dysregulated GnRH pulse generation, leading to a weak upstream signal for hormone production. |

Gonadorelin/Sermorelin ∞ Peptides that directly stimulate the pituitary, bypassing a potentially compromised hypothalamic signal to promote LH/FSH or GH release. |

| Pituitary Gland |

EDCs can interfere with pituitary cell receptors, altering the gland’s sensitivity to GnRH. |

Reduced secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). |

Clomiphene/Enclomiphene ∞ Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) that block estrogen feedback at the pituitary, increasing the gland’s output of LH and FSH to stimulate natural testosterone production. |

| Gonads (Testes/Ovaries) |

Direct inhibition of steroidogenic enzymes (e.g. P450scc, 17β-HSD) by phthalates and other chemicals. |

Impaired conversion of cholesterol to testosterone or estrogen, leading to primary hypogonadism. |

Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) ∞ Directly supplies the end-product hormone to restore physiological levels when the body’s own production machinery is impaired or insufficiently stimulated. |

| Peripheral Tissues |

Increased activity of the aromatase enzyme induced by certain EDCs; blocking of androgen receptors by competing chemicals. |

Elevated conversion of testosterone to estradiol; reduced biological action of testosterone at the cellular level. |

Anastrozole ∞ An aromatase inhibitor used to block the peripheral conversion of testosterone to estrogen, optimizing the androgen-to-estrogen ratio. |

This academic perspective reveals that addressing hormonal imbalance in the modern world is a complex task. It requires an appreciation for the subtle, cumulative, and persistent effects of environmental exposures. The protocols used in advanced wellness clinics are not merely replacing deficient hormones. They are sophisticated interventions designed to counteract specific points of disruption within the body’s core regulatory networks, restoring the integrity of the biological signals that are essential for health, vitality, and function.

References

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E. et al. “Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals ∞ An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 30, no. 4, 2009, pp. 293-342.

- Radke, E. G. et al. “Phthalate exposure and male reproductive health ∞ a review of the evidence and a framework for future research.” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 129, no. 3, 2021, p. 037003.

- Casals-Casas, C. and B. Piña. “Endocrine disruptors in the environment ∞ A review of the state of the art.” Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, vol. 69, no. 1, 2008, pp. 1-14.

- La Merrill, M. A. et al. “Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disrupting chemicals as a basis for hazard identification.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 16, no. 1, 2020, pp. 45-57.

- Gore, A. C. et al. “Executive Summary to EDC-2 ∞ The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 36, no. 6, 2015, pp. 593-602.

- De Coster, S. and N. van Larebeke. “Endocrine-disrupting chemicals ∞ associated disorders and mechanisms of action.” Journal of Environmental and Public Health, vol. 2012, 2012, Article ID 713696.

- Street, M. E. et al. “The impact of environmental factors and contaminants on thyroid function and disease from fetal to adult life ∞ current evidence and future directions.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 15, 2024, p. 1429884.

- Rehman, S. et al. “Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and their effects on the reproductive system.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 9, 2018, p. 546.

- Ferguson, K. K. et al. “Prenatal and peripubertal phthalates and bisphenol A in relation to sex hormones and puberty in boys.” Reproductive Toxicology, vol. 47, 2014, pp. 70-76.

- Mustieles, V. et al. “Bisphenol A ∞ human exposure and neurobehavioral effects.” Neurotoxicology, vol. 49, 2015, pp. 174-184.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map, connecting the subtle feelings of being unwell to complex, tangible biological processes. It traces a path from the plastics in our environment to the hormonal signals within our cells. This knowledge is not meant to cause alarm, but to serve as a tool for empowerment.

It reframes your personal health narrative, moving it from one of unexplained symptoms to one of understandable biological responses to modern challenges. Your body is not failing; it is responding to the inputs it receives.

Consider your own daily routines, your food choices, your personal care products, and your home environment. How might these elements be contributing to your body’s total biochemical load? This self-inquiry is not about assigning blame or striving for an impossible purity. It is about cultivating an awareness that allows you to make small, meaningful changes. It is the foundation for a more productive conversation with a clinical professional who understands this landscape.

Ultimately, your health journey is yours alone to navigate. The science provides the coordinates and the landmarks, but you hold the compass. Armed with a deeper understanding of your own intricate systems, you are better equipped to ask precise questions, seek out personalized data, and co-author a clinical strategy that actively restores the clarity and vitality that is your biological birthright.