Fundamentals

The conversation about your health often begins with a feeling. It might be a persistent fatigue that sleep doesn’t resolve, a subtle shift in your mood that you can’t quite pinpoint, or a change in your body’s composition despite your best efforts with diet and exercise. These experiences are valid and real.

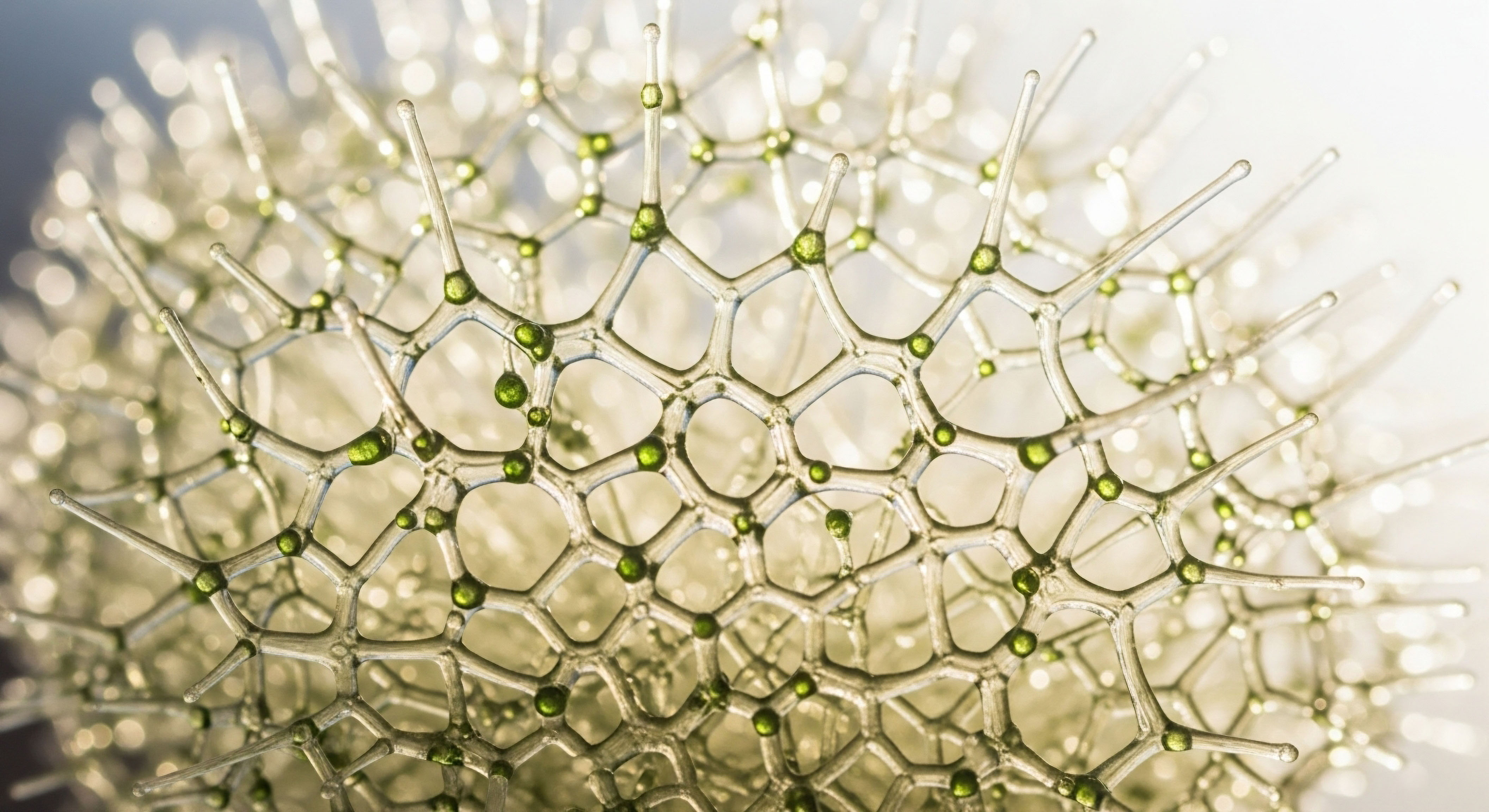

They are the body’s primary method of communication, sending signals that its internal equilibrium has been disturbed. Understanding the language of these signals is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality. At the heart of this communication network lies the endocrine system, an intricate web of glands that produce and release hormones.

These chemical messengers travel through your bloodstream, instructing cells and organs on what to do, how to grow, and how to function. The food you consume provides the direct building blocks for these essential messengers and profoundly influences their behavior.

Your body’s ability to manufacture hormones begins with the nutrients you extract from your diet. Think of your dietary intake as the raw material supplied to a highly sophisticated factory. Peptide hormones, which regulate processes like appetite and metabolism, are constructed from amino acids derived from the protein you eat.

Steroid hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, are synthesized from cholesterol, a lipid molecule obtained from dietary fats. Without an adequate supply of these foundational components, the body’s capacity to produce the precise amount of each hormone is compromised.

This is why a diet severely lacking in protein or healthy fats can lead to downstream disruptions in energy, reproductive health, and stress response. The quality of these raw materials matters immensely. The architecture of your hormonal health is built upon the nutritional choices you make with every meal.

The food you consume provides the direct building blocks for essential chemical messengers and profoundly influences their behavior.

The Central Role of Macronutrients

The three main classes of nutrients ∞ proteins, fats, and carbohydrates ∞ each play a distinct and cooperative role in hormonal regulation. Their balance is a key determinant of endocrine efficiency. A sufficient intake of protein at each meal, for instance, has a direct effect on the hormones that govern satiety.

Consuming protein-rich foods helps to suppress ghrelin, the hormone that signals hunger, while stimulating the production of hormones that promote a feeling of fullness. This biochemical event helps regulate appetite and supports stable energy levels, preventing the blood sugar fluctuations that can tax the adrenal system.

Dietary fats are equally significant, serving as the structural basis for all steroid hormones. Healthy fats, particularly omega-3 fatty acids found in fatty fish and certain nuts, also contribute to the fluidity of cell membranes. This is important because it enhances the sensitivity of hormone receptors.

A more sensitive receptor can receive its hormonal signal more effectively, meaning the body needs to produce less of the hormone to achieve the desired effect. This increases the efficiency of the entire system. Conversely, diets high in processed trans fats can create cellular inflammation and impair receptor function, contributing to a state of hormonal resistance.

Carbohydrates and the Insulin Connection

Carbohydrates are the primary drivers of insulin secretion, a hormone produced by the pancreas that allows your cells to absorb glucose from the blood for energy. The type and quantity of carbohydrates you consume dictate the body’s insulin response. Complex carbohydrates, rich in fiber, lead to a gradual release of glucose and a measured insulin response.

This promotes stable blood sugar and sustained energy. In contrast, refined sugars and simple carbohydrates cause a rapid spike in blood glucose, demanding a large and immediate surge of insulin. Over time, frequent and excessive insulin surges can lead to insulin resistance, a condition where cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals.

This state is a precursor to metabolic dysfunction and directly impacts other hormonal systems. High circulating insulin levels can, in women, stimulate the ovaries to produce more testosterone, and in both sexes, they can suppress levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), altering the balance of active sex hormones in the body.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational role of individual macronutrients, we can begin to analyze the effects of overarching dietary patterns on the endocrine system. Your body does not respond to single nutrients in isolation but to the complex synergy of your entire diet.

A dietary pattern is the cumulative result of your food choices over time, creating a specific biochemical environment that either supports or disrupts hormonal communication. Two well-researched patterns, the Western diet and the Mediterranean diet, offer a clear illustration of how different nutritional philosophies produce divergent hormonal outcomes.

The Western pattern, characterized by high intakes of processed foods, refined sugars, and saturated fats, is consistently linked to endocrine disruptions. The Mediterranean pattern, rich in whole foods, fiber, and healthy fats, is associated with more favorable hormonal profiles.

The mechanisms behind these differences are rooted in how each dietary pattern influences inflammation, gut health, and insulin sensitivity. The Western diet tends to be pro-inflammatory, creating a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation that interferes with hormonal signaling pathways. It can also negatively alter the composition of the gut microbiome.

Since the gut is a major site of hormone metabolism and regulation, particularly for estrogen, disruptions here can have systemic consequences. The Mediterranean diet, conversely, is anti-inflammatory due to its high content of polyphenols and omega-3 fatty acids. It also promotes a diverse and healthy gut microbiome through its abundance of fiber from vegetables, fruits, and legumes. This healthier internal environment facilitates more efficient and balanced hormonal activity.

A dietary pattern is the cumulative result of food choices over time, creating a biochemical environment that either supports or disrupts hormonal communication.

Comparing Dietary Impact on Key Hormones

Scientific studies have quantified the effects of different dietary patterns on specific endocrine biomarkers. Research in women has shown that greater adherence to healthful eating patterns like the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) or the Mediterranean diet is associated with significant improvements in key hormonal markers.

These improvements are not abstract; they have direct implications for metabolic health, reproductive function, and how you feel day to day. Understanding these connections allows for a more targeted approach to nutrition, where food is used as a tool to help recalibrate specific biological systems.

For instance, one of the most consistent findings is the effect of these diets on Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). SHBG is a protein that binds to sex hormones, primarily testosterone and estrogen, and transports them in the blood. When hormones are bound to SHBG, they are inactive.

Only the “free” portion of the hormone can bind to cell receptors and exert its effects. Healthful dietary patterns have been shown to increase SHBG levels. This is significant because higher SHBG can be protective, and it alters the ratio of free to total hormones, a critical factor in both male and female hormonal health and a key consideration when designing hormone replacement protocols.

| Biomarker | Association with DASH Diet Adherence | Association with Mediterranean Diet Adherence | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) |

Significantly Higher |

Significantly Higher |

Influences the amount of active testosterone and estrogen. Higher levels can be protective against certain conditions. |

| Leptin |

Significantly Lower |

No Significant Association |

Leptin is the “satiety” hormone. Lower levels, in the context of a healthy weight, can indicate better leptin sensitivity and appetite regulation. |

| Triglycerides |

Significantly Lower |

Significantly Lower |

A key marker of metabolic health. Lower levels are associated with better insulin sensitivity and lower cardiovascular risk. |

| C-Peptide |

Significantly Lower |

No Significant Association |

A marker of insulin production. Lower levels suggest the body needs to produce less insulin to manage blood sugar, indicating better insulin sensitivity. |

How Does Diet Influence Hormonal Therapies?

The principles of dietary hormonal regulation are especially relevant for individuals undergoing hormonal optimization protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for men or women. The body’s internal environment, shaped by diet, can significantly influence the efficacy and safety of these treatments.

For example, a pro-inflammatory diet can increase the activity of the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone into estrogen. For a man on TRT, this could lead to elevated estrogen levels and associated side effects, potentially requiring higher doses of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole. A diet rich in anti-inflammatory foods, similar to the Mediterranean pattern, can help manage this conversion process naturally, creating a more favorable hormonal balance and potentially reducing the need for ancillary medications.

Similarly, insulin resistance driven by a high-sugar diet can lower SHBG levels. For an individual on TRT, this means that more of the administered testosterone will be in its “free,” active form. While this may seem desirable, it can lead to a more rapid conversion to estrogen and other metabolites, and may not be optimal for all tissues.

By improving insulin sensitivity through a diet rich in fiber and healthy fats, one can support healthier SHBG levels, leading to a more stable and balanced hormonal state while on therapy. The diet becomes a foundational element that works in concert with clinical protocols to achieve optimal outcomes.

Academic

A deeper analysis of the relationship between dietary patterns and hormonal regulation requires an examination of adipose tissue as a dynamic and influential endocrine organ. Body fat is a metabolically active tissue that synthesizes and secretes a host of signaling molecules known as adipokines, which include leptin and adiponectin, as well as various inflammatory cytokines.

The specific dietary composition of fats and carbohydrates directly modulates the function of this adipose-endocrine axis, thereby exerting profound control over systemic metabolic and reproductive hormonal systems, including the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

The Western dietary pattern, high in saturated fatty acids and refined carbohydrates, promotes both adipocyte hypertrophy (increase in fat cell size) and hyperplasia (increase in fat cell number). This expansion, particularly in visceral adipose tissue, leads to a state of localized hypoxia and cellular stress, triggering an inflammatory response.

Stressed adipocytes secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and Interleukin-6. These molecules spill into the systemic circulation, creating a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state that directly impairs insulin receptor signaling and interferes with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulsatility in the hypothalamus. This disruption to the HPG axis can manifest as suppressed luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) output from the pituitary, ultimately leading to lower gonadal steroid production in both men and women.

Adipose tissue functions as a dynamic endocrine organ, and its behavior is directly programmed by the composition of the diet.

Dietary Lipids and Steroidogenesis

The type of dietary fat consumed has a direct impact on the cellular mechanisms of steroidogenesis. Steroid hormones, including testosterone, are synthesized from cholesterol. While the body can produce its own cholesterol, dietary fat intake influences the lipid environment of steroidogenic cells in the gonads and adrenal glands.

Diets rich in omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (common in many vegetable oils and processed foods) can promote an inflammatory intracellular environment. Conversely, diets containing a higher ratio of omega-3 fatty acids (from sources like fatty fish) to omega-6 fatty acids contribute to the production of anti-inflammatory eicosanoids.

This lipid-mediated inflammatory balance within the cell can influence the efficiency of the enzymatic steps that convert cholesterol into pregnenolone and subsequently into other steroid hormones. A pro-inflammatory lipid environment can impair mitochondrial function, and since the initial steps of steroidogenesis are mitochondrial, this can reduce the overall output of key hormones.

- Saturated Fatty Acids (SFAs) ∞ Primarily found in animal fats and some tropical oils, high intake is associated with increased systemic inflammation and insulin resistance, which can indirectly suppress HPG axis function.

- Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFAs) ∞ Found in olive oil, avocados, and nuts, these fats are a core component of the Mediterranean diet and are associated with improved insulin sensitivity and a more favorable inflammatory profile.

- Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) ∞ This category includes both omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. The ratio between them is critical. The typical Western diet has a high omega-6 to omega-3 ratio, promoting inflammation. A diet with a balanced ratio supports reduced inflammation and better cell membrane health, enhancing hormone receptor sensitivity.

What Is the Role of Caloric Intake versus Composition?

A critical question in endocrinology is the relative importance of total energy intake versus the macronutrient composition of the diet. Both play a role. Caloric restriction, for example, has been shown to modulate hormonal balance, but its effects are complex and context-dependent.

In a state of significant caloric deficit, the body may downregulate reproductive hormonal axes as a survival mechanism, reducing testosterone and estrogen production. However, for an individual with obesity and insulin resistance, a state of caloric excess is the primary driver of hormonal disruption. In this context, reducing caloric intake is necessary.

Within that caloric budget, the composition of the diet determines the specific hormonal response. A low-carbohydrate diet, for instance, primarily works by reducing insulin levels, which can have beneficial effects on SHBG and androgen balance. A Mediterranean diet, even if not strictly low-carbohydrate, achieves similar benefits through its anti-inflammatory properties and high fiber content.

| Dietary Pattern | Primary Mechanism | Effect on Adipose Tissue | Downstream Hormonal Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Diet |

High saturated fat and refined sugar intake. |

Promotes adipocyte hypertrophy, inflammation, and secretion of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6). |

Induces insulin resistance and leptin resistance. Suppresses HPG axis via inflammation, potentially lowering testosterone and disrupting female cycles. |

| Low-Carbohydrate Diet |

Reduced glucose and insulin signaling. |

Reduces lipid storage, improves insulin sensitivity in adipocytes, decreases inflammation. |

Lowers circulating insulin, increases SHBG, and can improve androgen profiles in conditions like PCOS. May improve leptin sensitivity. |

| Mediterranean Diet |

High intake of MUFAs, omega-3s, and polyphenols. |

Reduces inflammation, promotes secretion of anti-inflammatory adiponectin. |

Enhances insulin sensitivity, supports healthy SHBG levels, and provides a favorable environment for balanced steroidogenesis. |

Ultimately, the evidence suggests that for hormonal regulation, dietary composition is a powerful lever. By shifting the dietary pattern away from one that promotes inflammation and insulin resistance toward one based on whole foods, healthy fats, and high fiber, it is possible to fundamentally alter the signaling environment of the body.

This creates a foundation of metabolic health that supports the optimal function of the HPG axis, the thyroid, and the adrenal systems, and enhances the effectiveness of any clinical hormonal interventions.

References

- Guzzo, Filomena, et al. “Obesity, Dietary Patterns, and Hormonal Balance Modulation ∞ Gender-Specific Impacts.” Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 11, 2024, p. 1629.

- Tobias, Deirdre K. et al. “Dietary patterns and cardiometabolic and endocrine plasma biomarkers in US women.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 105, no. 2, 2017, pp. 526-533.

- Kubala, Jillian. “10 Natural Ways to Balance Your Hormones.” Healthline, 2022.

- Huizen, Jennifer. “Hormonal imbalance ∞ Symptoms, causes, and treatment.” Medical News Today, 2024.

- Stanworth, R. D. & Jones, T. H. “Testosterone for the aging male ∞ current evidence and recommended practice.” Clinical interventions in aging, vol. 3, no. 1, 2008, pp. 25-44.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map, detailing the intricate connections between what you eat and how your internal communication network functions. It validates the feelings and symptoms that may have initiated your search for answers, grounding them in the elegant, complex science of human physiology. This knowledge is the starting point.

Your own biological system is unique, shaped by a lifetime of experiences, genetic predispositions, and environmental inputs. The path toward reclaiming your optimal function involves understanding these general principles and then applying them to your individual context. Consider where your own patterns lie and how they might be influencing the signals your body is sending you. This awareness is the first, most definitive step on a personal journey toward lasting vitality.