Fundamentals

You feel it in your bones, a subtle yet persistent sense that your body’s internal rhythm is off. It might manifest as a fatigue that sleep doesn’t resolve, a frustrating change in your body composition despite your best efforts, or a mood that feels untethered from your daily circumstances. This experience, this feeling of being out of sync, is a valid and deeply personal signal. It is your body communicating a disruption in its most fundamental language, the language of hormones.

Your hormonal system is an intricate communication network, a constant, flowing conversation between glands and tissues that dictates everything from your energy levels to your reproductive health. The food you consume is a primary modulator of this conversation. Every meal, every snack, every beverage introduces a stream of information that can either clarify and support this internal dialogue or introduce static and disruption. Understanding this relationship is the first step toward reclaiming control over your biological function.

At the heart of this system are specific hormonal axes that are exquisitely sensitive to dietary inputs. These are not isolated pathways; they are interconnected and constantly influencing one another. By appreciating how our nutritional choices speak to these systems, we can begin to consciously shape the conversation.

We can move from being passive recipients of our body’s signals to active participants in our own wellness. This journey begins with understanding the primary messengers and the messages they carry.

The Insulin and Glucose Dialogue

Perhaps the most immediate and direct dietary-hormonal interaction is the one between the foods you eat and the hormone insulin. When you consume carbohydrates and, to a lesser extent, protein, they are broken down into glucose and amino acids, which enter your bloodstream. This rise in blood sugar signals the pancreas to release insulin, a hormone whose primary job is to act as a key, unlocking your cells to allow glucose to enter and be used for energy. This is a vital, life-sustaining process.

A well-regulated insulin response Meaning ∞ The insulin response describes the physiological adjustments occurring within the body, particularly in insulin-sensitive tissues, following the release and action of insulin. ensures that your brain, muscles, and organs receive the fuel they need in a steady, controlled manner. The system is designed for efficiency and balance.

The type, quantity, and combination of macronutrients you consume directly dictate the intensity and duration of this insulin signal. Diets rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars trigger a rapid, high-volume release of insulin. Over time, a pattern of these intense signals can lead to a state known as insulin resistance, where the cells become less responsive to insulin’s message. The pancreas then compensates by producing even more insulin, leading to chronically elevated levels.

This high-insulin state is a powerful disruptive force in the body’s hormonal symphony. It can interfere with the balanced production of other hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, and is a foundational element in many metabolic disorders. Conversely, dietary patterns Meaning ∞ Dietary patterns represent the comprehensive consumption of food groups, nutrients, and beverages over extended periods, rather than focusing on isolated components. rich in fiber, healthy fats, and adequate protein promote a more modulated, gentle insulin response, preserving cellular sensitivity and fostering a stable hormonal environment.

The composition of your meals directly programs your body’s insulin response, which in turn influences a wide spectrum of other hormonal pathways.

Cortisol and the Rhythm of Stress

Cortisol is often labeled the “stress hormone,” a description that captures only a fraction of its true role. It is more accurately understood as the hormone of alertness and readiness, following a natural daily rhythm. Cortisol levels are highest in the morning to help you wake up and face the day, gradually declining to their lowest point at night to allow for rest and repair.

This rhythm is governed by a sophisticated feedback loop known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Dietary patterns represent a significant external input that can either support or disrupt this delicate rhythm.

Large swings in blood sugar are a potent physiological stressor. When blood sugar drops too low, a condition known as hypoglycemia, the body perceives it as an emergency and releases cortisol to mobilize stored glucose and bring levels back to normal. A dietary pattern characterized by long periods without food followed by large meals of refined carbohydrates can create a volatile cycle of blood sugar spikes and crashes, leading to dysregulated cortisol output. Chronic inflammation, often driven by diets high in processed foods and unhealthy fats, also signals the HPA axis Meaning ∞ The HPA Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine system orchestrating the body’s adaptive responses to stressors. to maintain a state of high alert, contributing to chronically elevated cortisol.

This disruption can manifest as feeling “wired but tired,” experiencing poor sleep, accumulating abdominal fat, and feeling a persistent sense of anxiety. Supporting the natural cortisol rhythm involves creating metabolic stability through balanced meals, consistent meal timing, and a focus on anti-inflammatory foods.

Thyroid Hormones the Metabolic Thermostat

The thyroid gland, located at the base of your neck, functions as the body’s metabolic thermostat. It produces thyroid hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which travel to nearly every cell in the body to regulate the rate at which you burn energy. A healthy thyroid function Meaning ∞ Thyroid function refers to the physiological processes by which the thyroid gland produces, stores, and releases thyroid hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), essential for regulating the body’s metabolic rate and energy utilization. is synonymous with vitality; it supports energy production, maintains body temperature, and influences heart rate, digestion, and even cognitive function. The production of these critical hormones is entirely dependent on the availability of specific raw materials obtained from your diet.

The synthesis of thyroid hormones Meaning ∞ Thyroid hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), are crucial chemical messengers produced by the thyroid gland. is a complex process that requires a specific set of micronutrients. Iodine is the most critical component, forming the very backbone of T4 and T3 molecules. Without sufficient iodine, the thyroid gland simply cannot produce its hormones, a condition that can lead to hypothyroidism and goiter. Selenium is another essential mineral that plays a dual role.

It is a component of the enzymes that convert the less active T4 hormone into the more potent T3 form within your cells. Selenium also functions as a powerful antioxidant within the thyroid gland Meaning ∞ The thyroid gland is a vital endocrine organ, positioned anteriorly in the neck, responsible for the production and secretion of thyroid hormones, specifically triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). itself, protecting it from the oxidative stress generated during hormone synthesis. Other nutrients, like zinc and iron, also act as important cofactors in this process. A diet lacking in these key micronutrients can directly impair the thyroid’s ability to function, leading to symptoms like fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, and brain fog. Therefore, a nutrient-dense dietary pattern is a prerequisite for a healthy metabolic rate.

| Macronutrient | Primary Hormonal Interaction | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | Insulin and Glucagon |

Directly influences blood glucose levels, triggering insulin release for energy storage. The type of carbohydrate (complex vs. simple) determines the magnitude and speed of this response. |

| Proteins | Insulin, Glucagon, and Peptide Hormones |

Provides the amino acid building blocks for peptide hormones (like GH) and transport proteins. It also stimulates a moderate insulin response and a strong glucagon response, promoting satiety and blood sugar stability. |

| Fats | Steroid Hormones and Eicosanoids |

Dietary cholesterol and fatty acids are the direct precursors for all steroid hormones, including testosterone, estrogen, and cortisol. Fats also influence inflammatory pathways through the production of eicosanoids. |

Intermediate

Understanding that diet influences hormones is the first step. The next is to appreciate the intricate mechanisms and feedback loops that govern these interactions. Your endocrine system Meaning ∞ The endocrine system is a network of specialized glands that produce and secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream. operates through a series of sophisticated axes, such as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which controls reproductive hormones, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which manages the stress response. These are not linear pathways but dynamic, responsive systems.

The nutritional information your body receives can fundamentally alter the sensitivity and function of these axes, determining whether they operate in a state of balance or dysfunction. This deeper level of understanding allows us to see how specific dietary strategies can be used to support and recalibrate these vital systems, forming the biological rationale for personalized wellness protocols.

How Do Macronutrients Program Hormonal Signals?

Macronutrients are more than just calories; they are signaling molecules that provide specific instructions to your endocrine system. The ratio and quality of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins in your diet create a distinct hormonal milieu that can either promote metabolic flexibility and health or drive the body toward a state of imbalance. This programming occurs at a cellular level, influencing hormone synthesis, transport, and receptor sensitivity.

Carbohydrates and Insulin-Mediated Signaling

The glycemic load of a meal, a measure of how much it raises blood glucose, is a powerful hormonal switch. High-glycemic foods cause a rapid surge in insulin. Chronically elevated insulin has profound downstream effects, particularly on sex hormones. In women, high insulin levels can stimulate the ovaries to produce more testosterone, a key factor in the pathophysiology of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).

It also reduces the production of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Meaning ∞ Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin, commonly known as SHBG, is a glycoprotein primarily synthesized in the liver. (SHBG) in the liver. SHBG is a protein that binds to testosterone and estrogen in the bloodstream, keeping them in an inactive state. When SHBG levels fall, the amount of free, biologically active testosterone and estrogen rises, which can contribute to hormonal imbalances. In men, chronic insulin resistance can impair the function of the Leydig cells in the testes, leading to lower testosterone production. Therefore, managing carbohydrate intake to ensure a stable, low-insulin environment is a cornerstone of hormonal optimization.

Fats as Steroid Hormone Precursors

Dietary fats, particularly cholesterol, are the essential raw material for the synthesis of all steroid hormones. This family of hormones includes cortisol, DHEA, testosterone, and the various forms of estrogen. Without an adequate supply of cholesterol and specific types of fatty acids, the body’s ability to produce these critical signaling molecules is compromised. This is why extremely low-fat diets can sometimes be associated with hormonal disruptions, including amenorrhea in women and low testosterone in men.

The quality of dietary fats is also important. While saturated fats are necessary in moderation for hormone production, an overemphasis on them, particularly in the context of a high-sugar diet, can promote inflammation. In contrast, monounsaturated fats (found in olive oil and avocados) and polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids (found in fatty fish) have anti-inflammatory properties and support cell membrane health, which is crucial for proper hormone receptor function. This direct link between dietary fat and steroid hormone production Meaning ∞ Hormone production is the biological process where specialized cells and glands synthesize, store, and release chemical messengers called hormones. is the foundation upon which Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) is built; when the body’s own production falters, providing bioidentical hormones like Testosterone Cypionate Meaning ∞ Testosterone Cypionate is a synthetic ester of the androgenic hormone testosterone, designed for intramuscular administration, providing a prolonged release profile within the physiological system. can restore the necessary signaling.

Dietary fats are not merely an energy source; they are the fundamental building blocks for the entire class of steroid hormones that regulate stress, reproduction, and vitality.

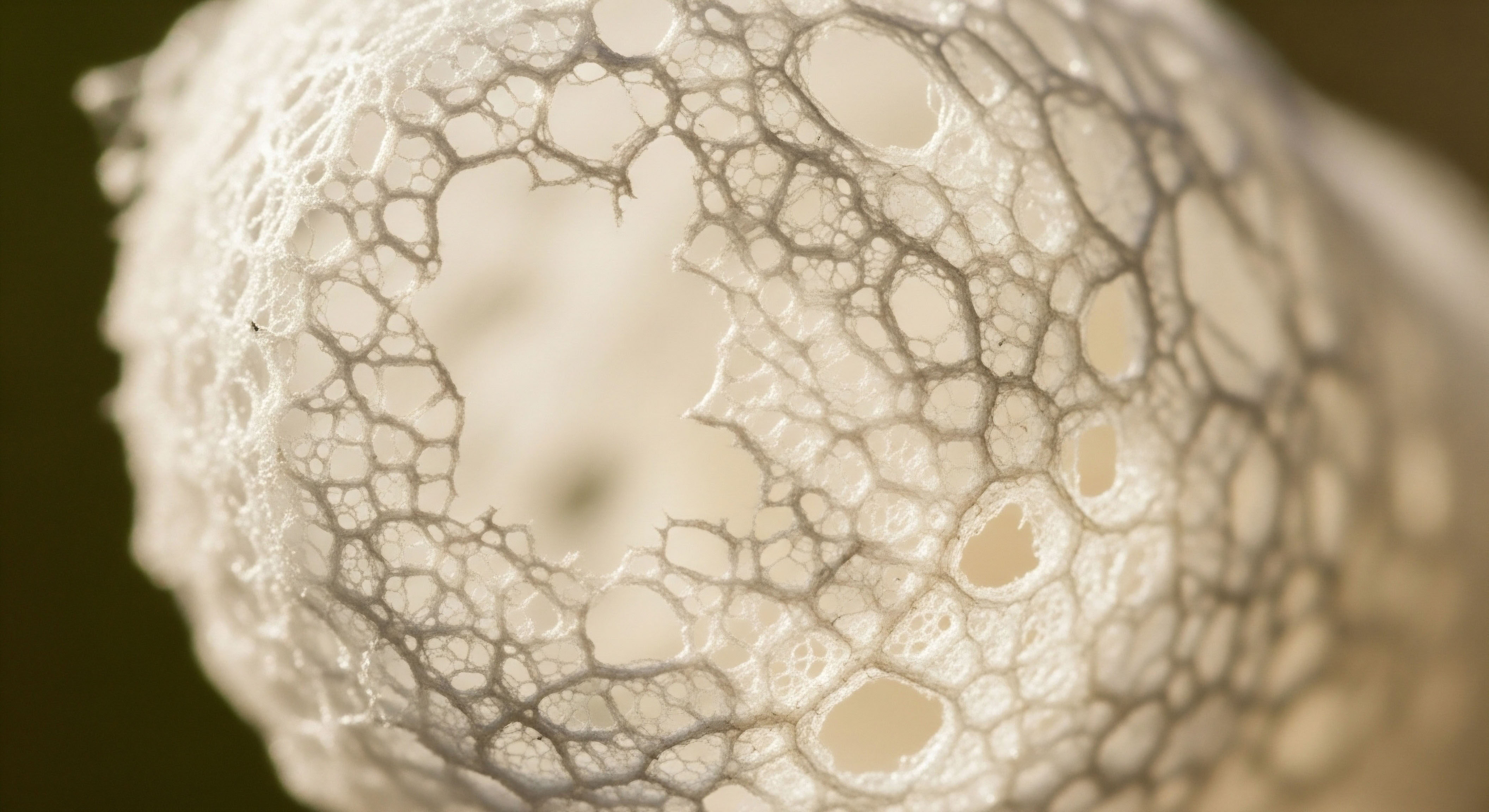

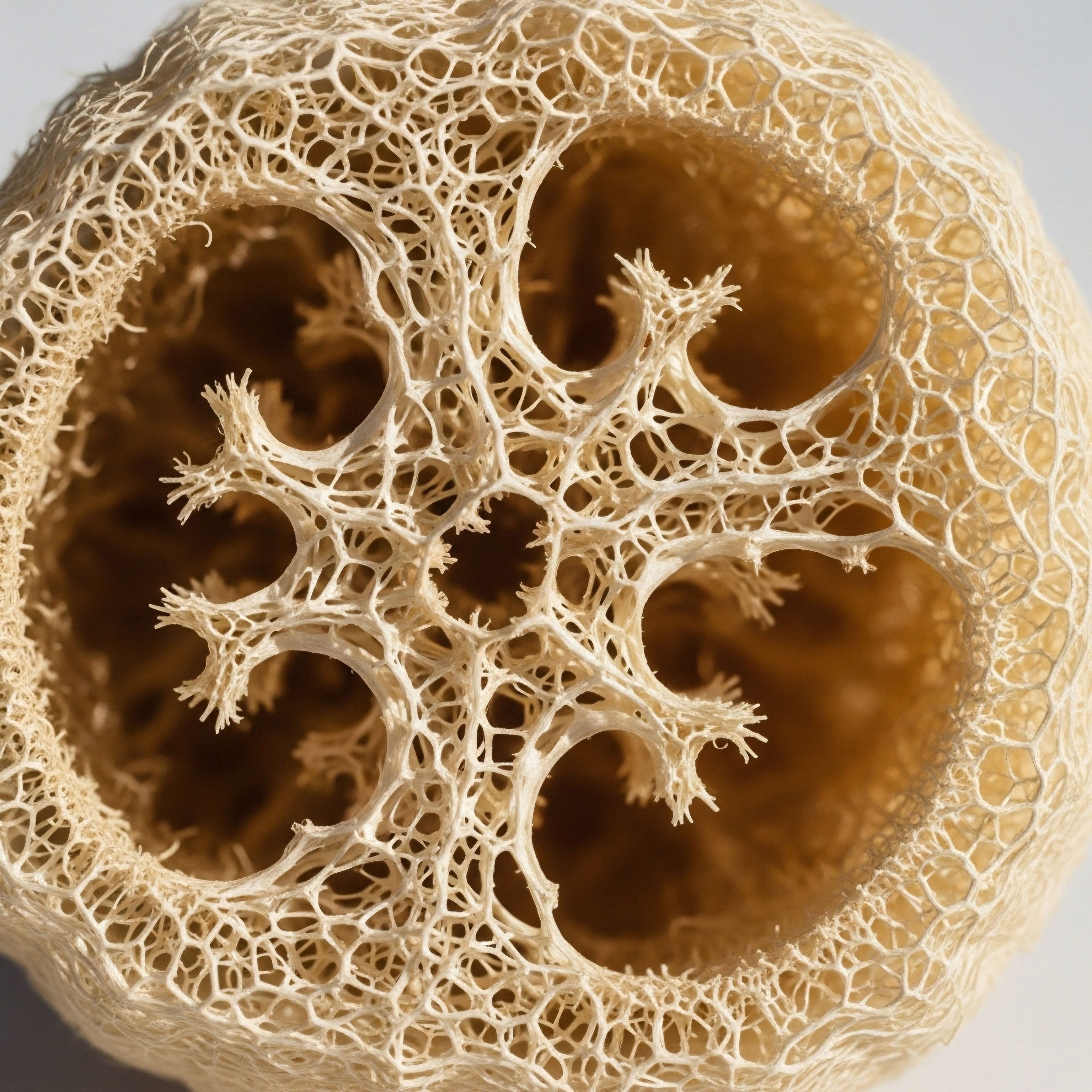

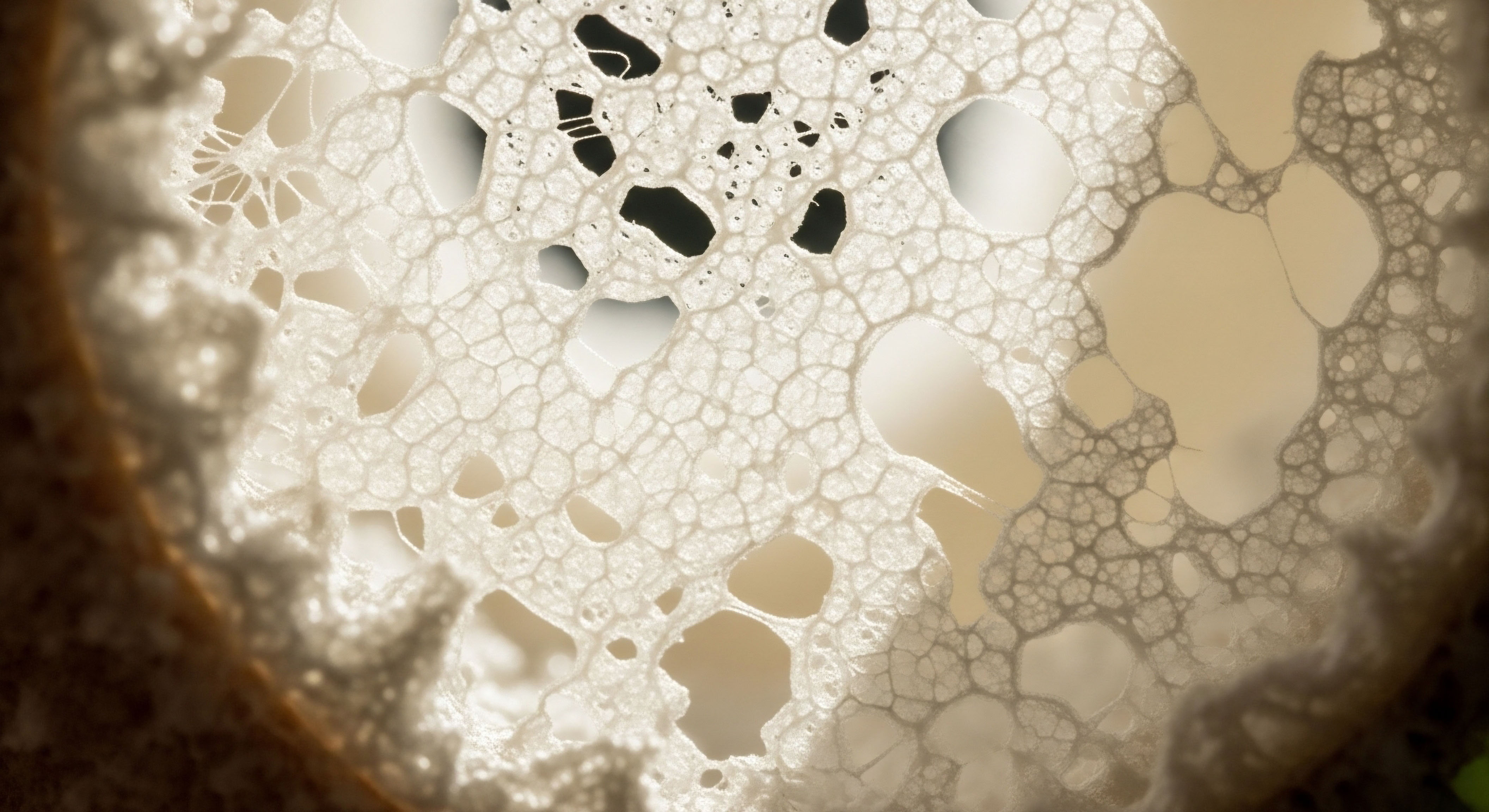

The Gut Microbiome the Hidden Endocrine Organ

The community of trillions of microorganisms residing in your gut is now recognized as a critical endocrine organ in its own right. This gut microbiome Meaning ∞ The gut microbiome represents the collective community of microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, viruses, and fungi, residing within the gastrointestinal tract of a host organism. plays a surprisingly direct role in regulating circulating hormone levels, particularly estrogen. A specific collection of gut bacteria, collectively known as the “estrobolome,” produces an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase.

This enzyme has a crucial function ∞ it deconjugates, or reactivates, estrogens that have been processed by the liver for excretion. This process allows estrogen to be reabsorbed into circulation, influencing systemic levels.

A healthy, diverse gut microbiome maintains a balanced level of beta-glucuronidase Meaning ∞ Beta-glucuronidase is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of glucuronides, releasing unconjugated compounds such as steroid hormones, bilirubin, and various environmental toxins. activity, contributing to normal estrogen homeostasis. However, a state of dysbiosis, or an imbalanced gut microbiota, can disrupt this process. Dysbiosis, often driven by a diet low in fiber and high in processed foods and sugar, can lead to either an underproduction or overproduction of beta-glucuronidase. Too little activity can result in lower circulating estrogen, while too much activity can lead to an excess of reactivated estrogen, contributing to conditions of estrogen dominance.

This gut-hormone axis highlights that hormonal health Meaning ∞ Hormonal Health denotes the state where the endocrine system operates with optimal efficiency, ensuring appropriate synthesis, secretion, transport, and receptor interaction of hormones for physiological equilibrium and cellular function. is inextricably linked to digestive health. Dietary strategies that nurture a diverse microbiome, such as consuming a wide variety of plant fibers and fermented foods, are a direct intervention for supporting hormonal balance.

- Iodine ∞ An essential component of thyroid hormones (T4 and T3). Found in seaweed, fish, and iodized salt. Its deficiency is a leading cause of hypothyroidism worldwide.

- Selenium ∞ Required for the enzyme that converts T4 to the active T3. It also has antioxidant properties that protect the thyroid gland. Brazil nuts, seafood, and organ meats are rich sources.

- Zinc ∞ Plays a role in the synthesis of thyroid hormones and also helps the hypothalamus regulate the entire thyroid axis. Oysters, red meat, and pumpkin seeds are good sources.

- Iron ∞ The enzyme thyroid peroxidase, which is essential for hormone production, is iron-dependent. Iron deficiency can impair thyroid function, especially in menstruating women.

- Vitamin D ∞ Functions as a hormone itself and helps modulate the immune system. Low levels are associated with an increased risk of autoimmune thyroid conditions like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

| Dietary Pattern | Description | Primary Hormonal Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Western Diet |

High in processed foods, refined carbohydrates, sugar, and unhealthy fats. Low in fiber and micronutrients. |

Promotes insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and elevated cortisol. Can disrupt the HPG axis and lead to gut dysbiosis, impairing estrogen metabolism. |

| Mediterranean Diet |

Rich in whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, and olive oil. Moderate consumption of fish and dairy. |

Improves insulin sensitivity and reduces inflammation. Provides healthy fats for steroid hormone production and ample fiber to support a healthy gut microbiome. Enhances leptin sensitivity. |

| Low-Carbohydrate / Ketogenic Diet |

Very low in carbohydrates, high in fat, and moderate in protein. Shifts the body’s primary fuel source from glucose to ketones. |

Dramatically lowers insulin levels, which can be beneficial for insulin resistance. May alter cortisol metabolism and can impact thyroid hormone conversion (T4 to T3) in some individuals. |

| Plant-Based / Vegan Diet |

Excludes all animal products. Focuses on fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. |

Can be very high in fiber, supporting gut health. May be high in phytoestrogens. Requires careful planning to ensure adequate intake of key hormone-supportive nutrients like iron, B12, and zinc. |

Academic

A sophisticated examination of dietary influences on hormonal health moves beyond simple macronutrient ratios and into the complex, bidirectional communication between the gut microbiome and the host endocrine system. The estrobolome, defined as the aggregate of enteric bacterial genes capable of metabolizing estrogens, represents a critical control point in steroid hormone homeostasis. The functional activity of this microbial gene set directly modulates the enterohepatic circulation of estrogens, thereby influencing systemic exposure and the risk of developing estrogen-mediated pathologies.

Dietary patterns are the primary selective pressure shaping the composition and metabolic capacity of the gut microbiota, and by extension, the function of the estrobolome. This section will explore the molecular mechanisms through which diet modulates the estrobolome Meaning ∞ The estrobolome is the collection of gut bacteria that metabolize estrogens. and the subsequent implications for systemic inflammation Meaning ∞ Systemic inflammation denotes a persistent, low-grade inflammatory state impacting the entire physiological system, distinct from acute, localized responses. and hormonal health.

What Is the Molecular Mechanism of the Estrobolome?

Estrogens, primarily estradiol (E2) and its metabolites, are conjugated in the liver via glucuronidation and sulfation. This process renders them water-soluble and targets them for excretion via bile into the intestinal tract. Within the gut lumen, specific bacterial species possessing the gene for the enzyme β-glucuronidase can hydrolyze these glucuronide conjugates. This deconjugation liberates the estrogen, converting it back into its biologically active, unconjugated form.

This reactivated estrogen can then be reabsorbed through the intestinal epithelium into the portal circulation, returning to the systemic circulation to exert effects on target tissues. The efficiency of this process is a direct function of the composition and diversity of the gut microbiome. A microbiome characterized by high diversity and a balanced abundance of β-glucuronidase-producing bacteria contributes to the maintenance of physiological estrogen levels. Conversely, dysbiosis can significantly alter the pool of circulating estrogens.

Dietary Fiber and Microbial Diversity

The most potent dietary modulator of the gut microbiome is dietary fiber. Humans lack the enzymes to digest complex plant polysaccharides, which therefore arrive in the colon intact, where they serve as the primary substrate for microbial fermentation. A diet rich in a diverse array of fibers from various plant sources—fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains—promotes the growth of a diverse ecosystem of beneficial bacteria, including species from the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. This diversity is associated with a more stable and resilient microbiome.

The fermentation of fiber produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate. Butyrate, in particular, serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, maintaining the integrity of the gut barrier. A strong gut barrier prevents the translocation of inflammatory molecules like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from the gut lumen into circulation, a key driver of systemic inflammation that can disrupt endocrine function. By fostering a diverse microbiome, a high-fiber diet helps to normalize the activity of the estrobolome Meaning ∞ The estrobolome refers to the collection of gut microbiota metabolizing estrogens. and reduce the inflammatory load on the body.

Polyphenols and Phytoestrogens

Polyphenols are a class of plant-derived compounds with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. They also act as prebiotics, selectively promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria. Phytoestrogens, such as the isoflavones found in soy and the lignans found in flaxseed, are a subclass of polyphenols with a structural similarity to human estradiol. Their biological activity is profoundly dependent on metabolism by the gut microbiota.

For example, the soy isoflavone daidzein can be metabolized by certain gut bacteria into equol, a metabolite with significantly higher estrogenic potency than its precursor. However, only about 30-50% of the Western population possesses the specific gut bacteria required to produce equol. This inter-individual variability in gut microbiota Meaning ∞ The gut microbiota refers to the collective community of microorganisms, primarily bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses, that reside within the gastrointestinal tract, predominantly in the large intestine. composition explains the inconsistent results often seen in clinical studies of soy isoflavones. The hormonal effect of a phytoestrogen-rich food is not determined by the food alone, but by the interaction between the food and the host’s unique microbial fingerprint. This underscores the necessity of a personalized approach to dietary recommendations for hormonal health.

The gut microbiome functions as a personalized filter for dietary compounds, determining the ultimate bioavailability and biological activity of hormonal modulators like phytoestrogens.

Systemic Inflammation the Link between Dysbiosis and Endocrine Disruption

A low-fiber, high-sugar, high-saturated-fat Western-style diet promotes a low-diversity gut microbiome and can compromise the integrity of the intestinal barrier. This “leaky gut” allows for the translocation of bacterial endotoxins like LPS into the bloodstream, triggering a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state. This systemic inflammation is a powerful disruptor of endocrine function. Inflammatory cytokines can interfere with insulin signaling, contributing to insulin resistance.

They can also activate the HPA axis, leading to dysregulated cortisol patterns. Furthermore, inflammation within the liver can impair its detoxification and conjugation functions, affecting how it processes hormones for excretion. The dysbiosis that drives this inflammation also directly alters estrobolome activity, potentially leading to elevated levels of reactivated estrogen. This combination of elevated estrogen and systemic inflammation is implicated in the pathophysiology of numerous conditions, including endometriosis, PCOS, and certain hormone-sensitive cancers. Therapeutic interventions, from dietary changes to targeted peptide therapies like Pentadeca Arginate (PDA) which supports tissue repair, aim to quell this underlying inflammation to restore systemic balance.

The intricate crosstalk between diet, the gut microbiome, and the endocrine system represents a paradigm for understanding health and disease. It illustrates that hormonal balance is not a static state but a dynamic equilibrium that is constantly being negotiated at the interface of our genetics, our diet, and our resident microbes. Clinical protocols that aim to restore hormonal health, whether through TRT, peptide therapy, or other interventions, are most effective when they are supported by dietary strategies that address these foundational biological systems. A diet that promotes microbial diversity, strengthens the gut barrier, and reduces systemic inflammation is a prerequisite for creating an internal environment where hormonal optimization is possible and sustainable.

References

- Baker, J. M. Al-Nakkash, L. & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. “Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

- Ervin, S. M. Li, H. Lim, L. Roberts, L. R. & Chia, N. “Gut microbial beta-glucuronidase ∞ a vital regulator in female estrogen metabolism.” Gut Microbes, vol. 14, no. 1, 2022, 2155214.

- Garelli, S. et al. “Role of iodine, selenium and other micronutrients in thyroid function and disorders.” Endocrine, vol. 42, no. 2, 2012, pp. 265-75.

- Kolan, S. D. et al. “Adaptive Effects of Endocrine Hormones on Metabolism of Macronutrients during Fasting and Starvation ∞ A Scoping Review.” Metabolites, vol. 14, no. 1, 2024, p. 36.

- Kwa, M. Plottel, C. S. Blaser, M. J. & Adams, S. “The Estrobolome ∞ The Gut Microbiome and Estrogen.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 8, 2016, djw024.

- Messina, M. Mejia, S. B. Cassidy, A. et al. “Neither soyfoods nor isoflavones warrant classification as endocrine disruptors ∞ a technical review of the observational and clinical data.” Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, vol. 62, no. 21, 2022, pp. 5824-5885.

- Paterni, I. Granchi, C. & Minutolo, F. “Phytoestrogens in breast cancer ∞ a new opportunity for an old player?” Current Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 24, no. 6, 2017, pp. 609-629.

- Pucciarelli, D. et al. “Obesity, Dietary Patterns, and Hormonal Balance Modulation ∞ Gender-Specific Impacts.” Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 9, 2024, p. 1386.

- Stimson, R. H. et al. “Dietary macronutrient content alters cortisol metabolism independently of body weight changes in obese men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 92, no. 11, 2007, pp. 4480-4.

- Triggiani, V. et al. “The role of nutrition on thyroid function.” Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 25, no. 3, 2024, pp. 497-515.

Reflection

A Conversation with Your Biology

The information presented here provides a map, a detailed guide to the intricate biological terrain that connects your plate to your hormonal state. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of confusion or frustration with your body’s signals to one of understanding and collaboration. The symptoms you may be experiencing are not random; they are a form of communication.

Your body is reporting on its internal environment, and your dietary patterns are one of the most significant inputs shaping that environment. The path forward involves listening to this feedback with a new level of awareness.

Consider your own daily choices. How do they feel in your body, not just in the moment, but hours later? What patterns do you notice in your energy, your mood, your sleep? This process of self-inquiry, informed by a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms, is the true beginning of a personalized wellness journey.

The science provides the framework, but your lived experience provides the essential data. This journey is about moving from a rigid set of external rules to an intuitive, informed, and continuous conversation with your own biology, creating a foundation upon which lasting vitality can be built.