Fundamentals

You feel it in your body. That subtle shift in energy after a meal, the creeping brain fog in the afternoon, or the sense that your internal engine isn’t running with the same power it once did. These experiences are the language of your body, a direct communication from your endocrine system.

This intricate network of glands and hormones is constantly responding to the world around you, and most intimately, to the fuel you provide. The connection between the food on your plate and the precise function of your hormonal orchestra is one of the most direct and powerful levers you have for reclaiming your vitality.

We can begin to understand this relationship by viewing the primary components of your diet ∞ proteins, fats, and carbohydrates ∞ as more than just calories. They are, in fact, potent informational molecules. Each macronutrient provides the raw materials for building hormones and simultaneously sends distinct signals that instruct your body on how to behave.

Your daily dietary choices compose a set of instructions that can either support robust hormonal health or contribute to the very symptoms that leave you feeling depleted and out of sync. Understanding these instructions is the first step toward rewriting your personal health narrative.

The Architects and the Messengers

Your hormones are sophisticated messengers, dispatched from endocrine glands to carry out specific tasks throughout the body. Think of testosterone, estrogen, cortisol, and insulin. Their jobs range from regulating metabolism and managing stress to building muscle and governing reproductive health. For these messengers to be created and sent, the body requires a steady supply of specific building blocks. This is where macronutrients perform their first critical role.

Dietary fats and the cholesterol they contain are the direct precursors for all steroid hormones. This category includes the sex hormones testosterone and estrogen, as well as cortisol, the primary stress hormone. Without an adequate intake of healthy fats, the very foundation for producing these vital regulators is compromised.

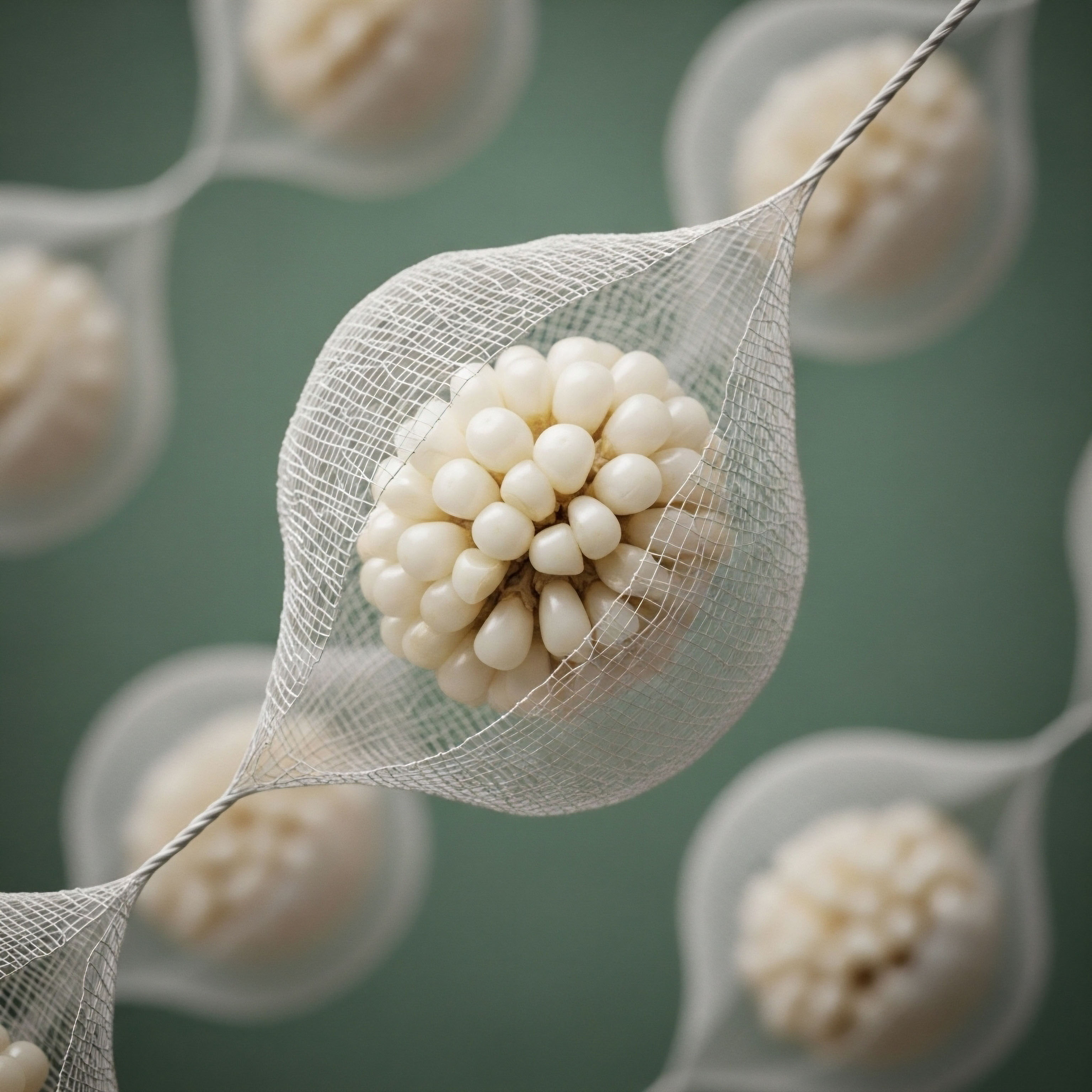

Proteins, composed of amino acids, are the building blocks for peptide hormones. This group includes insulin, which manages blood sugar, and growth hormone, which is essential for cellular repair and regeneration. The availability of these macronutrients is the starting point for all endocrine function; a deficiency in the raw materials means the production line for your hormones cannot run efficiently.

Your diet provides the foundational building blocks your body requires to manufacture its essential hormonal messengers.

Carbohydrates the Body’s Primary Fuel and Key Signal

Carbohydrates are the body’s preferred source of immediate energy. When you consume them, they are broken down into glucose, which enters the bloodstream. This rise in blood glucose signals the pancreas to release insulin, a hormone whose primary job is to shuttle that glucose into your cells to be used for energy.

This mechanism is a perfect example of a direct hormonal response to a macronutrient. The type and quantity of carbohydrates you consume dictate the intensity of this insulin signal.

Complex carbohydrates, like those found in vegetables and whole grains, are digested slowly, leading to a gradual and controlled release of insulin. Refined sugars and processed starches, conversely, cause a rapid spike in blood glucose and a subsequent surge of insulin.

Over time, consistently high insulin levels can lead to a condition known as insulin resistance, where your cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals. This state of metabolic disruption has profound downstream consequences for other hormonal systems, particularly affecting the balance of testosterone and estrogen. It is a clear demonstration of how a single dietary choice, repeated over time, can alter the function of the entire endocrine system.

What Are the Foundational Roles of Dietary Fats?

Fats are essential for life, performing roles that extend far beyond energy storage. They form the structure of every cell membrane in your body, enabling communication between cells. Critically, they are the raw material for steroid hormone synthesis. The body uses cholesterol, derived from dietary fats or produced internally, as the molecular backbone to create testosterone, the estrogens (estradiol, estrone, estriol), progesterone, and cortisol.

The quality of the fats you consume is immensely important. A diet rich in anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids (found in fatty fish) and monounsaturated fats (found in olive oil and avocados) supports healthy cellular function and can modulate inflammatory pathways that might otherwise disrupt hormone signaling.

Conversely, high intakes of certain processed vegetable oils and trans fats can promote inflammation, potentially interfering with hormonal balance at a cellular level. Your fat intake directly influences the structural integrity of your cells and the availability of precursors for your most vital steroid hormones.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational roles of macronutrients, we can begin to appreciate the intricate feedback loops that govern your endocrine system. Your body is in a constant state of communication with itself, and your diet provides the primary vocabulary for this conversation.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, the central command line for reproductive health in both men and women, is exquisitely sensitive to metabolic signals derived from your food intake. This axis involves a cascade of hormonal signals, starting in the brain and ending at the gonads (testes or ovaries), and its proper function is deeply intertwined with energy availability and metabolic status.

When the body perceives a state of chronic energy deficit or metabolic stress ∞ often a result of very low-calorie or extremely low-carbohydrate diets ∞ the hypothalamus may downregulate its release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This is a protective mechanism, a signal that the body does not have sufficient resources to support reproductive function.

The consequence is a reduced signal to the pituitary gland, leading to lower production of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). For men, this can result in decreased testosterone production from the Leydig cells in the testes. For women, it can manifest as irregular menstrual cycles or amenorrhea. This demonstrates that macronutrient intake influences the very top of the hormonal command chain.

Insulin’s Far Reaching Influence on Sex Hormones

The hormonal consequences of dietary choices are rarely isolated. The effects of insulin, for example, extend far beyond blood sugar management. Chronic high insulin levels, a hallmark of insulin resistance driven by a diet high in refined carbohydrates, can directly impact sex hormone balance through several mechanisms.

In both men and women, high insulin levels can decrease the production of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), a protein produced by the liver that binds to sex hormones in the bloodstream. SHBG acts as a transport vehicle, but while hormones are bound to it, they are inactive.

When SHBG levels drop, the amount of “free” testosterone and estrogen increases. While this might sound beneficial, the excess free hormones can lead to negative consequences. In women, elevated free androgens can contribute to symptoms associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). In men, the excess free testosterone is more readily converted to estrogen by the aromatase enzyme, particularly in the presence of excess adipose tissue, potentially leading to an unfavorable estrogen-to-testosterone ratio.

The metabolic state created by your carbohydrate intake directly modulates the availability and activity of your primary sex hormones.

The Aromatase Connection

Aromatase is an enzyme that converts androgens (like testosterone) into estrogens. Its activity is influenced by several factors, including age, genetics, and, critically, body fat levels and insulin resistance. Adipose tissue is a primary site of aromatase activity. Therefore, a higher body fat percentage, often linked to a diet promoting fat storage, can increase the rate of this conversion.

This is a key consideration in male hormone optimization protocols. A man undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) with underlying insulin resistance may find that a significant portion of the administered testosterone is being converted into estradiol, leading to side effects like water retention and mood changes.

This is why TRT protocols for men often include an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole, and why dietary strategies aimed at improving insulin sensitivity and reducing body fat are a crucial component of a successful hormonal optimization plan.

How Does Protein Intake Support Endocrine Function?

Protein’s role in hormonal health extends to its influence on other key hormones and metabolic processes. Adequate protein intake is necessary for maintaining muscle mass, which is metabolically active tissue that helps improve insulin sensitivity. A meal containing sufficient protein also promotes satiety, helping to regulate appetite and prevent the overconsumption of calorie-dense, nutrient-poor foods that can drive hormonal imbalance.

Furthermore, protein consumption stimulates the release of glucagon, a hormone that works in opposition to insulin to help stabilize blood sugar levels. It also provides the amino acid building blocks for thyroid hormones and catecholamines (like adrenaline), which are integral to metabolic rate and stress response. The balance of macronutrients within a meal shapes the cumulative hormonal response.

The table below illustrates how different dietary patterns, defined by their macronutrient composition, can create distinct hormonal environments within the body.

| Dietary Pattern | Primary Macronutrient Focus | Key Hormonal Influences | Potential Clinical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Diet | High in Refined Carbohydrates and Saturated/Trans Fats |

Chronically elevated insulin; increased aromatase activity; potential for suppressed SHBG; increased inflammatory markers. |

Associated with insulin resistance, obesity, and an unfavorable estrogen-to-testosterone ratio in men. May exacerbate symptoms of PCOS in women. |

| Low-Fat, High-Carbohydrate | Low in all Fats, High in Carbohydrates (often refined) |

Can lead to reduced production of steroid hormones (testosterone, estrogen) due to lack of fat/cholesterol precursors. Potential for insulin spikes if carbohydrate quality is poor. |

Studies have linked very low-fat diets to lower total and free testosterone levels in men. May be suboptimal for individuals requiring robust steroid hormone support. |

| Ketogenic/Very Low-Carb | Very High in Fats, Adequate Protein, Very Low in Carbohydrates |

Lowers insulin levels significantly; improves insulin sensitivity. May increase SHBG. Can sometimes increase cortisol in the initial adaptation phase. |

Can be effective for managing insulin resistance. However, some individuals, particularly women, may experience HPA axis disruption if not implemented carefully. |

| Mediterranean Diet | Balanced Macronutrients; Focus on Monounsaturated Fats, Complex Carbs, and Lean Protein |

Promotes insulin sensitivity; provides healthy fats for steroid hormone production; reduces inflammation; supports healthy SHBG levels. |

Widely regarded as a supportive dietary pattern for overall metabolic and hormonal health, providing a balanced foundation for endocrine function. |

Nutritional Support for Advanced Protocols

For individuals undertaking specific therapeutic protocols, such as Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy, diet is a critical synergistic factor. Peptides like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin work by stimulating the pituitary gland to release more of the body’s own growth hormone. This process is energy-intensive and requires adequate biological resources.

- Protein Adequacy ∞ Growth hormone is anabolic, meaning it promotes building tissues like muscle. This cannot occur without a sufficient supply of amino acids from high-quality protein sources. A diet lacking in protein will blunt the therapeutic effects of the peptide protocol.

- Insulin Management ∞ Growth hormone release is naturally blunted by high levels of insulin. To maximize the effectiveness of a peptide injection, it is often administered during a fasted state, such as before bed or in the morning, when insulin levels are low. Consuming a high-sugar meal around the time of injection would directly counteract the therapy’s mechanism of action.

- Micronutrient Cofactors ∞ The enzymatic pathways involved in hormone production and action rely on various vitamins and minerals. Zinc is crucial for testosterone production, while magnesium and Vitamin D are involved in hundreds of metabolic processes that support overall endocrine health. A whole-foods diet rich in these micronutrients is essential.

Academic

A granular analysis of macronutrient influence on hormonal regulation requires an examination of the direct biochemical interactions occurring at the cellular level. The synthesis of steroid hormones, a process termed steroidogenesis, is particularly sensitive to the quantity and composition of dietary lipids.

This process, occurring primarily within the mitochondria of steroidogenic cells like the Leydig cells of the testes and the theca cells of the ovaries, is fundamentally dependent on cholesterol as the initial substrate. While the body can synthesize cholesterol de novo, dietary fat intake significantly modulates the lipid environment, influencing both substrate availability and the efficiency of enzymatic conversions.

Acute postprandial studies provide compelling evidence of this direct modulation. Research has demonstrated that a high-fat meal can induce a significant, albeit transient, reduction in serum testosterone concentrations, with decreases of up to 30% observed within hours of ingestion. This phenomenon is believed to be mediated by several mechanisms.

One proposed pathway involves the release of inflammatory cytokines from intestinal cells in response to a large fat bolus, which can have a suppressive effect on the HPG axis at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary.

Another mechanism involves direct lipotoxicity within the steroidogenic cells themselves, where an acute influx of certain fatty acids may impair mitochondrial function and the activity of key steroidogenic enzymes like StAR (Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory Protein), which is the rate-limiting step in transporting cholesterol into the mitochondria.

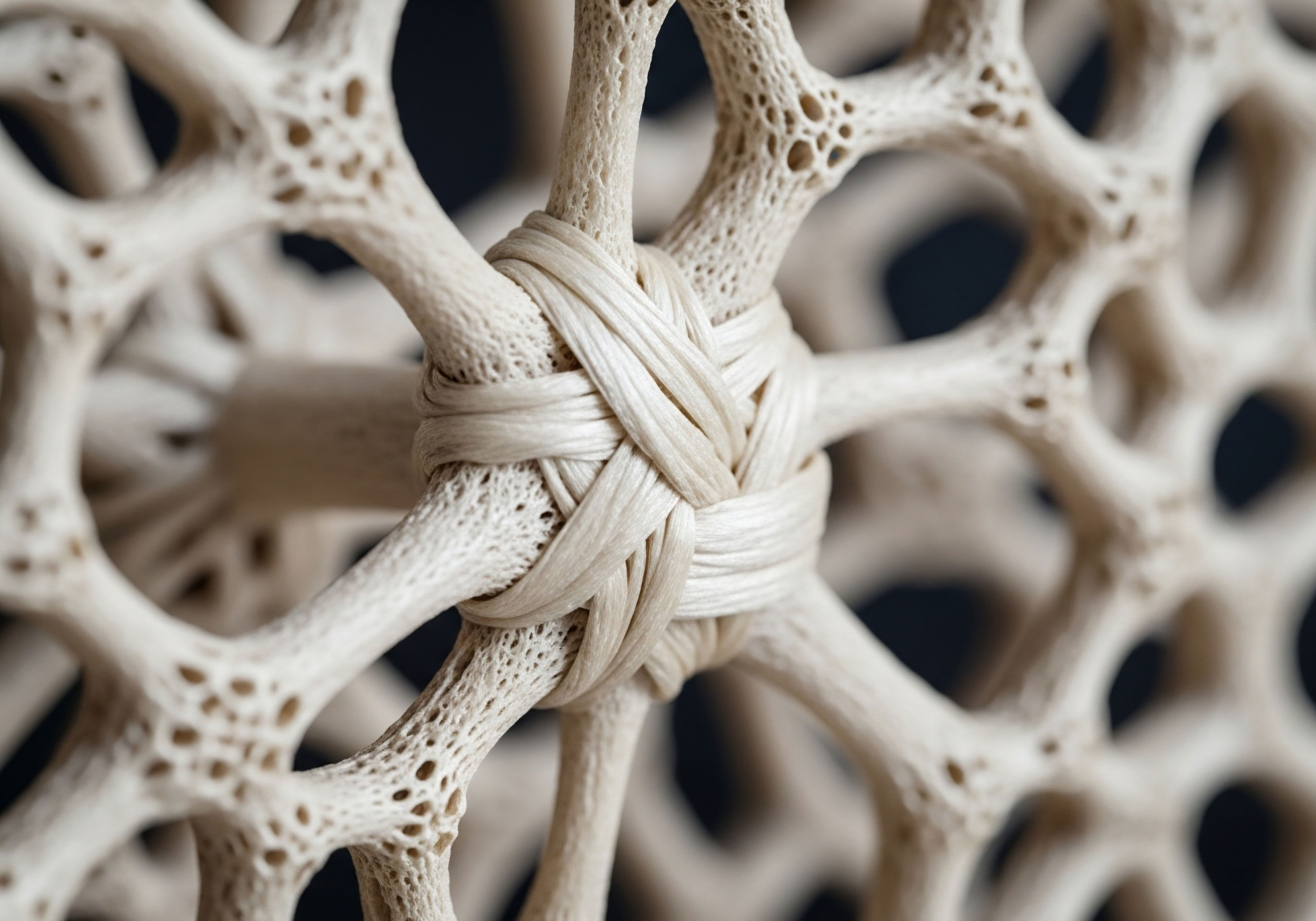

The specific type of fatty acid consumed initiates distinct downstream effects on the enzymatic pathways of hormone production.

Fatty Acid Composition and Steroidogenic Enzyme Activity

The impact of dietary fat extends beyond the total quantity to the specific composition of fatty acids consumed. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and saturated fatty acids (SFAs) exert differential effects on hormonal profiles. For instance, some studies suggest that diets higher in MUFAs and SFAs are positively associated with resting testosterone levels, while high PUFA intake may be inversely associated. This can be understood by examining their roles at the cellular membrane and in intracellular signaling.

The cell membranes of Leydig cells are rich in lipid rafts, specialized microdomains that serve as organizing centers for receptors and signaling molecules. The fluidity and composition of these rafts, which are influenced by dietary fatty acid intake, affect the efficiency of LH receptor signaling.

LH from the pituitary gland binds to its receptor on the Leydig cell, initiating a cAMP-mediated signaling cascade that upregulates the expression and activity of steroidogenic enzymes. A diet that alters the lipid composition of these membranes could thereby enhance or inhibit the cell’s response to a given LH signal.

Furthermore, PUFAs, particularly omega-6 fatty acids, are precursors to pro-inflammatory eicosanoids that can directly suppress the expression of enzymes like P450scc (Cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme) and 17β-HSD (17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), which are critical for converting cholesterol into testosterone.

The following table details the observed associations between specific classes of fatty acids and their influence on key male sex hormones, based on findings from nutritional endocrinology research.

| Fatty Acid Class | Primary Dietary Sources | Observed Effect on Testosterone | Observed Effect on Estradiol | Proposed Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated Fatty Acids (SFA) |

Red meat, dairy products, coconut oil |

Positive association with resting testosterone levels in some cross-sectional studies. |

Neutral or weakly positive association. |

May provide a stable lipid environment for mitochondrial function and steroidogenic enzyme activity. Serves as a direct substrate for energy production within Leydig cells. |

| Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA) |

Olive oil, avocados, nuts |

Positive association with resting testosterone levels. Some studies show less postprandial suppression compared to other fats. |

Generally neutral effect. |

Contributes to healthy cell membrane fluidity, potentially optimizing LH receptor function. Possesses anti-inflammatory properties. |

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) – Omega-6 |

Many vegetable oils (soy, corn, sunflower), processed foods |

Inverse association with testosterone levels, particularly at high intakes. Significant postprandial suppression observed. |

Variable; may increase with higher inflammation. |

Precursor to pro-inflammatory signaling molecules (e.g. arachidonic acid derivatives) that can suppress steroidogenic enzyme activity. May increase oxidative stress within steroidogenic cells. |

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) – Omega-3 |

Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), flaxseeds, walnuts |

Generally neutral or slightly positive effect; may improve the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio by reducing inflammation. |

May lower estradiol levels by reducing systemic inflammation and aromatase expression. |

Precursor to anti-inflammatory resolvins and protectins. Improves cell membrane fluidity and insulin sensitivity, indirectly supporting HPG axis function. |

Metabolic Endotoxemia and Hormonal Disruption

A particularly sophisticated mechanism linking diet to hormonal function is metabolic endotoxemia. This is a condition characterized by elevated levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the bloodstream. LPS is a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria found in the gut. A diet high in saturated fats and refined sugars can alter the gut microbiota and increase intestinal permeability, allowing LPS to “leak” from the gut into systemic circulation.

Once in the bloodstream, LPS acts as a potent inflammatory trigger, activating the innate immune system via Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). This systemic inflammation has a direct suppressive effect on the HPG axis. LPS has been shown in clinical models to inhibit GnRH release from the hypothalamus and to directly impair Leydig cell steroidogenesis.

This creates a powerful link between gut health, diet, and gonadal function. A dietary pattern that promotes a healthy gut barrier and a balanced microbiome is therefore a primary intervention for mitigating this source of hormonal disruption. This highlights the interconnectedness of seemingly disparate biological systems ∞ the gut, the immune system, and the endocrine system ∞ all responding to the same set of dietary inputs.

- Dietary Intervention ∞ A diet rich in fermentable fibers from vegetables and legumes supports the growth of beneficial bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate. Butyrate is a primary energy source for colonocytes and helps maintain tight junction integrity, reducing intestinal permeability.

- Reducing LPS Translocation ∞ Limiting the intake of high-SFA/high-sugar meals, which have been shown to acutely increase LPS translocation, can lower the systemic inflammatory burden.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids ∞ The anti-inflammatory properties of omega-3 PUFAs can help counteract the inflammatory cascade initiated by LPS, offering another layer of protection for the HPG axis.

References

- Whittaker, J. & Wu, K. (2021). Low-fat diets and testosterone in men ∞ Systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 210, 105878.

- Mínguez-Alarcón, L. Chavarro, J. E. & Mendiola, J. (2017). Fatty acid intake in relation to reproductive hormones and testicular volume among young healthy men. Asian Journal of Andrology, 19(2), 184 ∞ 190.

- Vingren, J. L. Kraemer, W. J. Ratamess, N. A. Anderson, J. M. Volek, J. S. & Maresh, C. M. (2010). Testosterone physiology in resistance exercise and training ∞ the up-stream regulatory elements. Sports Medicine, 40(12), 1037-1053.

- Pani, A. & Varghese, A. (2022). The effect of macronutrients on reproductive hormones in overweight and obese men ∞ A pilot study. Nutrients, 14(15), 3244.

- Salas-Huetos, A. Ros, E. & Salas-Salvadó, J. (2018). Dietary patterns, foods and nutrients in male fertility parameters and fecundability ∞ a systematic review of observational studies. Human Reproduction Update, 24(4), 371-389.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here offers a map, illustrating the profound and direct connections between your plate and your physiology. It details the mechanisms, the pathways, and the powerful influence of the fuel you choose. This knowledge is the first, most critical tool in your possession. It transforms the act of eating from a simple necessity into a conscious act of biological communication. You are now aware of the conversation.

The next step in this journey moves from the general map to your personal territory. Your unique genetic makeup, your life history, and your specific goals all shape how your body responds to these dietary signals. The true power lies in applying this understanding as a lens through which to view your own experience.

How does your energy shift? How does your focus change? Your body is providing constant feedback. Learning to listen, equipped with this new understanding, allows you to begin the process of personalized recalibration, moving toward a state of function and vitality that is authentically your own.

Glossary

endocrine system

steroid hormones

sex hormones

growth hormone

high insulin levels

insulin resistance

fatty acids

gnrh

luteinizing hormone

leydig cells

sex hormone-binding globulin

aromatase activity

testosterone replacement therapy

insulin sensitivity

testosterone levels

hormone production

steroidogenesis

hpg axis

with resting testosterone levels

polyunsaturated fatty acids

positive association with resting testosterone levels

steroidogenic enzyme activity

positive association with resting testosterone