Fundamentals

The experience of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) is one of profound biological and emotional upheaval. The cyclical nature of these feelings, which arise with predictable regularity in the luteal phase of your cycle, is a direct communication from your body’s intricate endocrine system.

Understanding how dietary choices can bring stability is a process of learning to interpret and respond to these signals. This journey begins with recognizing that the intense mood shifts you feel are linked to tangible, measurable changes within your neurochemistry and hormonal architecture.

Your body is not betraying you; it is responding to a complex series of internal events. By strategically adjusting what you eat, you can directly influence these events, providing your system with the raw materials it needs to maintain equilibrium.

The core of this dietary strategy rests on two foundational pillars ∞ managing inflammation and supporting neurotransmitter production. The hormonal fluctuations inherent to the menstrual cycle, particularly the rise and fall of progesterone and estrogen, can trigger a heightened inflammatory response in sensitive individuals.

This systemic inflammation is a key driver of both the physical discomfort and the psychological distress associated with PMDD. Concurrently, these same hormonal shifts impact the brain’s ability to produce and utilize serotonin, a critical neurotransmitter that governs mood, well-being, and impulse control. The dietary interventions that follow are designed to address these two interconnected systems, creating a biological environment that is more resilient to the cyclical hormonal tides.

The Inflammatory Cascade and Your Plate

Inflammation is a natural and necessary bodily process. When it becomes chronic or dysregulated, however, it contributes to a wide spectrum of symptoms. In the context of PMDD, studies have shown that levels of pro-inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and certain interleukins, increase during the luteal phase.

This elevation correlates with the worsening of mood symptoms. Your diet is one of the most powerful tools you have to modulate this inflammatory response. Foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, for instance, act as potent anti-inflammatory agents. These healthy fats are incorporated into the membranes of your cells, directly influencing cellular signaling pathways to reduce the production of inflammatory compounds.

A diet focused on whole, unprocessed foods provides the biochemical tools necessary to calm systemic inflammation and support stable neurotransmitter function.

Conversely, certain dietary patterns can promote inflammation. Diets high in processed foods, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats can create a pro-inflammatory state, exacerbating the underlying sensitivity to hormonal changes. These foods can lead to rapid spikes and crashes in blood sugar, which places additional stress on the body and can worsen feelings of irritability and anxiety.

Therefore, the first step in stabilizing mood through diet is to consciously shift your food choices away from those that fuel inflammation and toward those that quell it. This involves prioritizing whole, nutrient-dense foods that provide a steady supply of energy and anti-inflammatory compounds.

Building Your Mood with Serotonin Precursors

Serotonin is often called the “feel-good” neurotransmitter, and for good reason. It plays a central role in regulating mood, sleep, and appetite. Women with PMDD appear to have an altered sensitivity to the normal fluctuations of hormones, which in turn affects serotonin signaling in the brain.

Dietary choices can directly support serotonin production. The amino acid tryptophan is the essential building block for serotonin. While it is found in many protein sources, its ability to enter the brain is regulated by what you eat alongside it. Consuming carbohydrates triggers the release of insulin, which shunts other amino acids into muscle tissue, allowing tryptophan to more easily cross the blood-brain barrier.

This biological mechanism explains why cravings for carbohydrate-rich foods are so common in the premenstrual phase. Your brain is intelligently seeking the tools it needs to boost serotonin and improve your mood. By choosing complex carbohydrates, such as whole grains, legumes, and starchy vegetables, you provide a sustained release of glucose and facilitate a steady supply of tryptophan to the brain.

This strategic use of carbohydrates, paired with adequate protein intake, ensures that your brain has the necessary precursors to synthesize the serotonin required for emotional stability throughout the luteal phase.

Intermediate

Advancing beyond foundational principles requires a more granular understanding of the specific biochemical pathways that dietary interventions can modulate. For individuals with PMDD, this means targeting the neuro-inflammatory axis and optimizing the synthesis of key neurotransmitters with specific micronutrients.

The goal is to move from a generalized “healthy diet” to a targeted nutritional protocol designed to counteract the precise physiological disruptions that trigger PMDD symptoms. This involves a clinical appreciation for how specific vitamins, minerals, and food components interact with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axes.

Micronutrients as Hormonal and Neurotransmitter Cofactors

The biochemical reactions that govern mood and hormonal balance depend on a steady supply of specific micronutrients. These vitamins and minerals act as cofactors, or essential “helper molecules,” for the enzymes that drive these processes. Without them, the entire system can become inefficient, leading to the mood lability and physical symptoms characteristic of PMDD. Several micronutrients have been identified in clinical research as being particularly effective in mitigating symptoms.

- Calcium ∞ The relationship between calcium and premenstrual symptoms is well-documented. Circulating calcium levels can fluctuate with the menstrual cycle, and women with PMDD may have an underlying disruption in calcium homeostasis. Supplementation with calcium has been shown to improve symptoms of depression, fatigue, and appetite changes. It is thought to influence the synthesis and release of neurotransmitters.

- Magnesium ∞ This mineral is critical for nervous system regulation and plays a role in the function of the HPA axis. Magnesium deficiency can lead to increased anxiety and a heightened stress response. It works in concert with calcium and is also involved in the activity of GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter that promotes calmness.

- Vitamin B6 ∞ This vitamin is a crucial cofactor in the conversion of tryptophan to serotonin. It is also involved in the production of dopamine and GABA. Clinical trials have demonstrated that supplementing with Vitamin B6 can significantly reduce the emotional symptoms of PMS and PMDD, such as depression and irritability.

How Do Micronutrients Influence Brain Chemistry?

The influence of these micronutrients is not abstract; it is a matter of direct biochemical action. Vitamin B6, for example, is the rate-limiting cofactor for the enzyme aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, which catalyzes the final step in serotonin synthesis.

A deficiency or insufficiency of B6 can therefore create a bottleneck in this production line, limiting the amount of serotonin the brain can produce, even if adequate tryptophan is available. Similarly, magnesium is a modulator of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, a key player in synaptic plasticity and excitability. By regulating this receptor, magnesium helps to prevent neuronal over-stimulation, which can manifest as anxiety and agitation.

Targeted supplementation with key micronutrients like calcium and vitamin B6 provides the enzymatic machinery needed for stable serotonin production.

The following table outlines a sample daily supplementation protocol based on dosages found to be effective in clinical research for the management of PMDD symptoms. It is essential to consult with a healthcare provider before beginning any new supplementation regimen.

| Nutrient | Clinically Studied Dosage | Primary Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Carbonate | 1000-1200 mg/day | Modulates neurotransmitter synthesis and release; stabilizes mood and reduces fatigue. |

| Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) | 50-100 mg/day | Essential cofactor for serotonin and dopamine synthesis from amino acid precursors. |

| Magnesium Glycinate | 200-400 mg/day | Regulates HPA axis, supports GABAergic function, and calms neuronal excitability. |

Strategic Carbohydrate Intake for Serotonin Optimization

The timing and type of carbohydrate intake can be refined into a precise therapeutic tool. The “tryptophan-to-large-neutral-amino-acid” (Trp:LNAA) ratio in the blood is the determining factor for how much tryptophan enters the brain.

Large neutral amino acids (LNAAs), which include leucine, isoleucine, and valine, compete with tryptophan for the same transport channels across the blood-brain barrier. Protein-rich meals increase the levels of all these amino acids in the blood, meaning tryptophan faces significant competition and brain uptake is low.

A strategic, carbohydrate-rich meal, particularly in the evening, can dramatically shift this ratio in favor of tryptophan. The insulin released in response to the carbohydrate intake promotes the uptake of the competing LNAAs into skeletal muscle, effectively clearing the path for tryptophan.

One study demonstrated that a carbohydrate-rich, protein-poor evening meal significantly improved mood scores in women with PMS during their luteal phase. This intervention had no effect during the follicular phase or in control subjects, highlighting its specific utility for the PMDD state.

What Is the Optimal Way to Structure Meals?

A practical application of this principle involves structuring daily meals to support stable blood sugar and mood, with a specific emphasis on the luteal phase. This means avoiding large meals that are exclusively high in protein and ensuring that complex carbohydrates are included with each meal.

In the evening, or during times of heightened symptoms, a meal composed primarily of complex carbohydrates with only a small amount of protein can be particularly effective at promoting serotonin synthesis and improving mood and sleep quality.

Strategic consumption of complex carbohydrates manipulates the Trp:LNAA ratio, directly increasing the brain’s access to its primary mood-regulating building block.

The following table provides examples of meals structured to optimize the Trp:LNAA ratio and support mood stability in PMDD.

| Meal Timing | Meal Composition Goal | Example Meal |

|---|---|---|

| Daytime (Breakfast/Lunch) | Balanced Protein, Fat, and Complex Carbs | Grilled chicken or tofu salad with quinoa, mixed greens, avocado, and olive oil dressing. |

| Evening or Symptom Rescue | High Complex Carb, Low Protein | Large bowl of oatmeal with berries and a spoonful of seeds; or a baked sweet potato with a small amount of cinnamon. |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of dietary interventions for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder requires an integrated, systems-biology perspective. The condition’s etiology is understood as a paradoxical sensitivity of the central nervous system to normal cyclical fluctuations in gonadal steroids, rather than a hormonal imbalance per se.

This sensitivity appears to manifest as a dysregulation in key neurobiological systems, primarily the serotonergic and GABAergic systems, and is amplified by a feed-forward cycle of neuroinflammation. Dietary strategies, therefore, can be conceptualized as targeted biochemical interventions designed to restore homeostatic resilience within these interconnected networks.

The Serotonin-Kynurenine Pathway and Inflammatory Hijacking

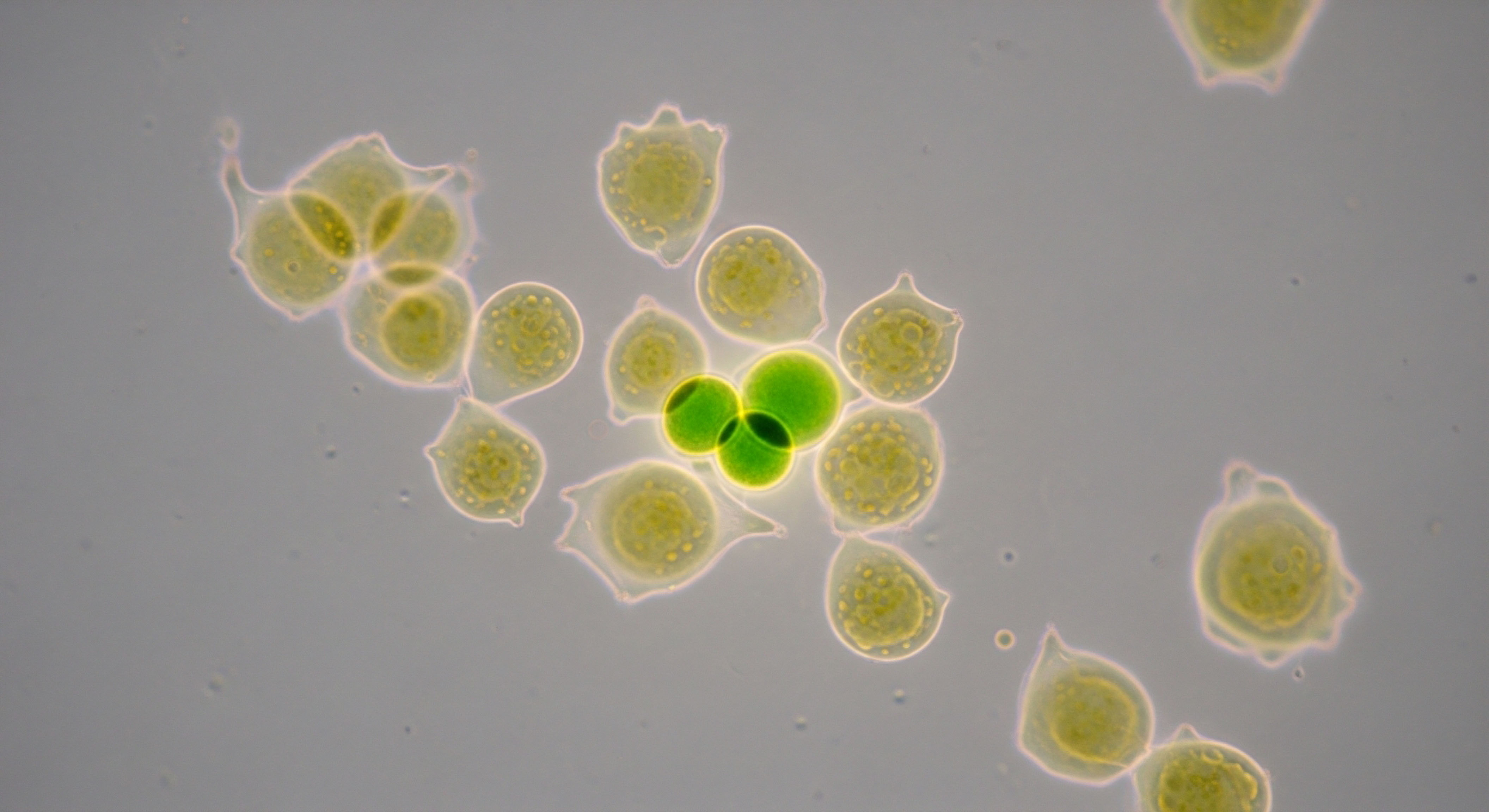

The metabolic fate of tryptophan is a critical control point influenced by both diet and inflammation. Under normal physiological conditions, the majority of tryptophan is metabolized via the kynurenine pathway. However, pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which are elevated in the luteal phase of women with PMDD, potently upregulate the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO).

IDO shunts tryptophan away from the serotonin synthesis pathway and toward the production of kynurenine and its downstream metabolites. This phenomenon is known as “tryptophan stealing.”

This process has two detrimental consequences for mood in PMDD. First, it directly reduces the availability of tryptophan for serotonin synthesis in the brain, contributing to the depressive and anxious-depressive symptoms. Second, certain metabolites of the kynurenine pathway are neurotoxic. For example, quinolinic acid is an NMDA receptor agonist that can promote excitotoxicity, anxiety, and neuronal damage.

In contrast, kynurenic acid is an NMDA antagonist and is generally considered neuroprotective. The balance between these metabolites is influenced by inflammatory signals, with inflammation often skewing production towards the more neurotoxic quinolinic acid. Dietary interventions that possess anti-inflammatory properties, such as those rich in omega-3 fatty acids and polyphenols, can theoretically mitigate the upregulation of IDO, preserving the tryptophan pool for serotonin synthesis and favoring a more neuroprotective kynurenine metabolite profile.

Allopregnanolone Sensitivity and GABAergic Dysregulation

The GABAergic system, the primary inhibitory network of the brain, is another key locus of dysregulation in PMDD. Allopregnanolone (ALLO), a potent neurosteroid metabolite of progesterone, is a positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor. It typically has anxiolytic and sedative effects.

In women with PMDD, there appears to be a paradoxical response to the normal luteal phase rise in ALLO. Instead of a calming effect, it may provoke negative mood symptoms. This suggests an altered configuration or sensitivity of the GABA-A receptors in these individuals.

Dietary factors can influence GABAergic tone. Specific micronutrients, including magnesium and Vitamin B6, are integral to GABA synthesis and receptor function. Furthermore, certain dietary components can directly interact with the GABAergic system. For example, flavonoids found in plant-based foods have been shown to modulate GABA-A receptor activity.

From a dietary intervention standpoint, ensuring an adequate supply of GABAergic cofactors while simultaneously implementing an anti-inflammatory diet to reduce systemic stress on the nervous system can help restore a more stable inhibitory tone. This approach aims to make the system less susceptible to the paradoxical effects of allopregnanolone fluctuations.

Can Diet Alter Neurosteroid Metabolism?

While diet may not directly alter the production of progesterone, it can influence the metabolic environment in which neurosteroids operate. The gut microbiome, which is profoundly shaped by dietary patterns, plays a role in steroid hormone metabolism.

A diet rich in fiber and fermented foods supports a diverse and healthy microbiome, which can influence circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines and potentially impact the peripheral metabolism of steroid hormones. A dysbiotic gut, often associated with a diet high in processed foods and low in fiber, can contribute to systemic inflammation, further exacerbating the central neuroinflammatory state seen in PMDD.

Therefore, a diet that supports gut health is a critical component of a systems-based approach to managing the disorder.

The following list details the key biological systems targeted by advanced dietary strategies for PMDD:

- The Serotonergic System ∞ Targeted by ensuring adequate tryptophan availability through strategic carbohydrate intake and providing essential enzymatic cofactors like Vitamin B6, zinc, and magnesium.

- The Inflammatory System ∞ Modulated by increasing the intake of anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids, polyphenols from fruits and vegetables, and reducing the consumption of pro-inflammatory processed foods and refined sugars.

- The GABAergic System ∞ Supported by providing key cofactors for GABA synthesis and receptor function, such as magnesium and Vitamin B6, and potentially through the intake of dietary flavonoids.

- The Gut-Brain Axis ∞ Optimized through a high-fiber diet that promotes a healthy microbiome, thereby reducing systemic inflammation and supporting hormonal homeostasis.

References

- Fathizadeh, N. Ebrahimi, E. Valiani, M. Tavakoli, M. & Yarali, M. (2010). Evaluating the effect of magnesium and magnesium plus vitamin B6 supplement on the severity of premenstrual syndrome. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 15(Suppl 1), 401 ∞ 405.

- Hantsoo, L. & Epperson, C. N. (2015). Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder ∞ Epidemiology and Treatment. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(11), 87.

- Sayegh, R. Schiff, I. Wurtman, J. Spiers, P. McDermott, J. & Wurtman, R. (1995). The effect of a carbohydrate-rich beverage on mood, appetite, and cognitive function in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 86(4 Pt 1), 520 ∞ 528.

- Thys-Jacobs, S. Starkey, P. Bernstein, D. & Tian, J. (1998). Calcium carbonate and the premenstrual syndrome ∞ effects on premenstrual and menstrual symptoms. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 179(2), 444-452.

- Ghafouryan-Oskuei, H. Vafisani, F. Tavakoli-Far, B. & Azadi, A. (2024). The role of the neuroinflammation and stressors in premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder ∞ a review. Psychiatria Danubina, 36(Suppl 2), 15-24.

- Wurtman, J. J. Brzezinski, A. Wurtman, R. J. & Laferrere, B. (1989). Effect of nutrient intake on premenstrual depression. The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 161(5), 1228 ∞ 1234.

- Masoumi, S. Z. Ataollahi, M. & Oshvandi, K. (2016). Effect of Combined Use of Calcium and Vitamin B6 on Premenstrual Syndrome Symptoms ∞ a Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Caring Sciences, 5(1), 67 ∞ 73.

- Bertone-Johnson, E. R. Hankinson, S. E. Bendich, A. Johnson, S. R. Willett, W. C. & Manson, J. E. (2005). Calcium and vitamin D intake and risk of incident premenstrual syndrome. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(11), 1246 ∞ 1252.

- Kwan, I. & Onwude, J. L. (2015). Premenstrual syndrome. BMJ Clinical Evidence, 2015, 0806.

- Diegoli, M. S. da Fonseca, A. M. Diegoli, C. A. & Pinotti, J. A. (1998). A double-blind trial of four medications to treat severe premenstrual syndrome. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 62(1), 63-67.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a biological roadmap, connecting the symptoms you experience to the intricate systems that govern your physiology. This knowledge transforms the conversation from one of managing distress to one of actively recalibrating your internal environment. Viewing your dietary choices as precise communications with your neuro-inflammatory and endocrine systems is a profound shift in perspective.

Each meal becomes an opportunity to provide stability, to reduce inflammatory noise, and to supply the very building blocks your brain needs to construct a more resilient sense of self. This journey of understanding is the first, most critical step. The path forward is one of self-biohacking, of listening to your body’s unique responses, and of recognizing that you possess the agency to architect a state of greater well-being.

Glossary

premenstrual dysphoric disorder

luteal phase

dietary interventions

systemic inflammation

omega-3 fatty acids

women with pmdd

tryptophan

complex carbohydrates

hpa axis

vitamin b6

serotonin synthesis

carbohydrate intake

neuroinflammation

kynurenine pathway

fatty acids