Fundamentals

You may feel a sense of disconnection from your body’s internal rhythms, a subtle yet persistent feeling that something is metabolically amiss. This experience is a valid and important signal. Understanding the intricate communication network within your body is the first step toward reclaiming a state of vitality.

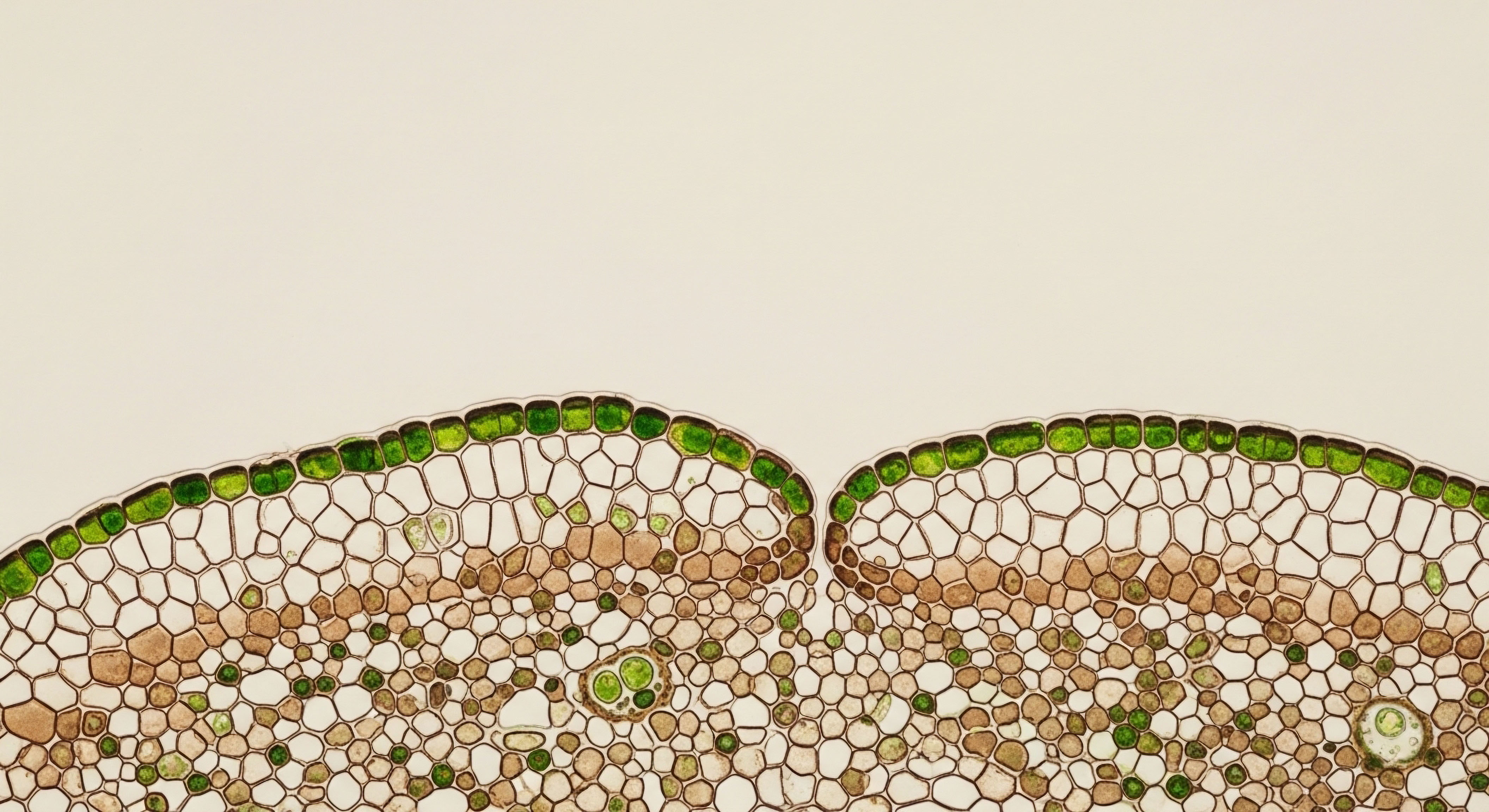

One of the most powerful levers we can pull to influence this network is through nutrition, specifically by modulating dietary fiber Meaning ∞ Dietary fiber comprises the non-digestible carbohydrate components and lignin derived from plant cell walls, which resist hydrolysis by human digestive enzymes in the small intestine but undergo partial or complete fermentation in the large intestine. intake. The relationship between what you eat and your hormonal state is direct, profound, and, most importantly, modifiable.

Estradiol, a primary form of estrogen, is a potent signaling molecule that governs countless processes, from reproductive health to bone density and cognitive function. Your body has a sophisticated system for managing its levels, ensuring there is enough to perform its duties without creating an excess that can lead to systemic disruption.

The liver is the primary site of estrogen metabolism, where it packages up used hormones for disposal. This disposal process is where dietary fiber enters the scene as a critical regulator.

The Excretory Pathway Aided by Fiber

Once the liver has processed estradiol, it is conjugated, or bound, to make it water-soluble and ready for elimination. This conjugated estrogen is excreted into the bile, which then flows into the intestines. Here, in the gut, a crucial series of events unfolds.

Dietary fiber, particularly soluble fiber Meaning ∞ Soluble fiber is a class of dietary carbohydrate that dissolves in water, forming a viscous, gel-like substance within the gastrointestinal tract. from sources like oats, flaxseeds, and beans, acts like a sponge. It physically binds to the conjugated estrogen in the gut. This binding action is fundamental because it prevents the estrogen from being reabsorbed back into the bloodstream. By securing the estrogen, fiber ensures it continues its journey out of the body through stool.

Regular bowel movements, promoted by a fiber-rich diet, are a non-negotiable aspect of this process. When transit time in the colon is slow, there is a greater opportunity for estrogen to be reabsorbed, potentially leading to an accumulation of circulating levels in the body. Thus, a diet sufficient in fiber supports the body’s natural clearance pathways, maintaining a healthy hormonal equilibrium.

A sufficient intake of dietary fiber directly supports the body’s ability to excrete excess estrogen, preventing its reabsorption from the gut.

The Gut Microbiome the Conductor of Hormonal Symphony

The gut is home to a complex ecosystem of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiome. This internal garden plays a direct role in your hormonal health through a specialized collection of bacteria referred to as the estrobolome. These specific microbes produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase.

This enzyme has the ability to “unpackage” or deconjugate the estrogen that the liver so carefully prepared for excretion. When deconjugated, the estrogen is reactivated and can re-enter circulation through the intestinal wall, a process called enterohepatic circulation.

This is where fiber’s role becomes even more nuanced. Fiber acts as a prebiotic, providing nourishment for beneficial gut bacteria. A healthy and diverse microbiome, supported by adequate fiber, helps maintain a balanced level of beta-glucuronidase Meaning ∞ Beta-glucuronidase is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of glucuronides, releasing unconjugated compounds such as steroid hormones, bilirubin, and various environmental toxins. activity.

An imbalanced gut, or dysbiosis, can lead to an overproduction of this enzyme, resulting in more estrogen being reactivated and reabsorbed than is optimal. By cultivating a healthy microbiome, you are directly influencing the final step of estrogen metabolism, ensuring that what is meant to be excreted, is.

Intermediate

Understanding the fundamental role of fiber in binding and excreting estrogen opens the door to a more sophisticated appreciation of the clinical mechanisms at play. The process is a beautiful example of systemic integration, where the liver, the gut, and the microbial world within us collaborate to maintain endocrine homeostasis. When we look closer, we see that the type of fiber and its interaction with specific microbial pathways can have distinct and measurable effects on circulating estradiol levels.

Glucuronidation and the Enterohepatic Circuit

To fully grasp fiber’s impact, we must first detail the process of estrogen metabolism. After circulating and delivering its messages, estradiol is transported to the liver. There, it undergoes Phase II detoxification, specifically a process called glucuronidation. An enzyme attaches a glucuronic acid molecule to estradiol, rendering it inactive and water-soluble. This newly formed estrogen conjugate is then secreted in bile into the small intestine, destined for fecal excretion.

This is where the enterohepatic circuit comes into play. It is a circulatory loop where substances excreted by the liver into the bile are reabsorbed from the intestine and returned to the liver. Certain bacteria within the gut’s estrobolome Meaning ∞ The estrobolome refers to the collection of gut microbiota metabolizing estrogens. produce the enzyme beta-glucuronidase.

This enzyme cleaves the glucuronic acid from the estrogen conjugate, reverting it to its active, fat-soluble form. In this state, it can be reabsorbed through the intestinal lining back into the bloodstream, effectively re-entering circulation and contributing to the body’s total estrogen load.

The gut enzyme beta-glucuronidase can reactivate estrogen that was prepared for excretion, allowing it to be reabsorbed into the body.

Dietary fiber intervenes directly in this circuit. Soluble fibers form a gel-like matrix in the intestine, which entraps bile acids and the bound estrogen within them. This sequestration physically prevents beta-glucuronidase from accessing the estrogen conjugates and also accelerates intestinal transit time, reducing the window for potential reabsorption. Studies have demonstrated that diets high in fiber are associated with increased fecal excretion of estrogens and consequently lower plasma estrogen levels.

Lignans and Phytoestrogens a Deeper Level of Modulation

Beyond the mechanical effects of bulk fiber, certain types of fiber contain compounds that actively modulate estrogen signaling. Lignans, found abundantly in flaxseeds, sesame seeds, and other whole grains, are phytoestrogens Meaning ∞ Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds structurally similar to human estrogen, 17β-estradiol. ∞ plant-derived compounds with a structure similar to mammalian estrogen.

When you consume lignans, your gut bacteria metabolize them into enterolignans, such as enterodiol and enterolactone. These compounds have a weak estrogenic effect. They can bind to estrogen receptors in the body, but their signaling power is much lower than that of endogenous estradiol. This binding action can have a balancing effect.

In situations of high estrogen, they can occupy receptors and block the more potent estradiol from binding. In situations of low estrogen, their weak activity can provide a minimal level of beneficial estrogenic signaling.

Research indicates a significant positive correlation between fiber intake Meaning ∞ Fiber intake refers to the quantity of dietary fiber consumed through food and supplements, which is crucial for gastrointestinal function and systemic health maintenance. and the urinary excretion of these beneficial lignans. Furthermore, higher lignan excretion has been negatively correlated with the percentage of free, active estradiol in the plasma. This suggests a dual benefit ∞ the fiber backbone aids in excretion while the lignans themselves help to buffer the body’s hormonal environment.

Comparing Fiber Sources and Hormonal Impact

Different types of fiber can have varied effects on hormone levels. The composition of the fiber, including its solubility and the presence of compounds like lignans, appears to be a determining factor. The table below summarizes findings from select studies on the topic.

| Fiber Source | Observed Effect on Estrogen | Potential Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Wheat Bran | Shown to significantly reduce serum estrone and estradiol in premenopausal women. | Primarily insoluble fiber, increasing fecal bulk and transit speed, which reduces time for estrogen reabsorption. |

| Oat and Corn Bran | In some studies, did not produce the same significant reduction in serum estrogens as wheat bran. | Different fiber composition and solubility profile, potentially leading to a different level of interaction with bile acids and the estrobolome. |

| Flaxseed | Associated with reduced circulating estrogen levels and changes in estrogen metabolism. | A rich source of both soluble fiber and lignans, providing a dual mechanism of binding/excretion and phytoestrogenic modulation. |

| Fruit Fiber | In one study, each 5-gram increase per day was associated with a higher probability of anovulation, linked to overall lower hormone concentrations. | May be related to the high soluble fiber content and its potent effect on reducing circulating hormone levels, including LH and FSH. |

Academic

A granular analysis of the interplay between dietary fiber and estradiol excretion reveals a complex biochemical and microbiological system. The conversation moves beyond simple binding and excretion to the specific enzymatic activities within the gut and the structural properties of different fiber types. This systems-biology perspective illuminates how nutritional inputs can produce precise and predictable modulations of endocrine function.

The Estrobolome and Beta-Glucuronidase Isoforms

The term “estrobolome” refers to the aggregate of enteric bacterial genes whose products are capable of metabolizing estrogens. Central to this concept is the enzyme beta-glucuronidase (GUS), which exists in multiple forms across different bacterial species in the gut. Recent research has identified distinct structural classes of microbial GUS enzymes, including “Loop 1,” “mini-Loop 1,” and “FMN-binding” classes. These classes exhibit varying efficiencies in deconjugating different estrogen glucuronides, such as estrone-3-glucuronide and estradiol-17-glucuronide.

This enzymatic specificity is clinically significant. The composition of an individual’s gut microbiome Meaning ∞ The gut microbiome represents the collective community of microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, viruses, and fungi, residing within the gastrointestinal tract of a host organism. ∞ and therefore their specific portfolio of GUS enzymes ∞ could dictate the efficiency of estrogen reactivation in their gut. A microbiome rich in bacteria that produce highly efficient GUS enzymes may lead to greater reabsorption of free estrogens, contributing to a higher systemic estrogenic burden. This has been hypothesized as a contributing factor in the pathophysiology of hormone-receptor-positive cancers and other estrogen-dependent conditions.

The specific types of beta-glucuronidase enzymes present in the gut microbiome determine the rate at which estrogen is reactivated for reabsorption.

Dietary fiber influences this system profoundly. High-fiber diets alter the gut microbial composition, favoring the proliferation of species that may produce less or lower-activity GUS. For example, fiber fermentation produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which lower the gut pH. This lower pH can inhibit the activity of some bacterial GUS enzymes, thereby reducing the deconjugation of estrogens and facilitating their excretion.

How Does Fiber Intake Affect Ovulation?

The BioCycle Study, a prospective cohort study of healthy premenopausal women, provided compelling evidence linking high fiber intake to significant hormonal changes. The study found that dietary fiber consumption was inversely associated with concentrations of estradiol, progesterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

For every 5-gram per day increase in total fiber, researchers observed a 1.78-fold increased risk of an anovulatory cycle. This suggests that a very high fiber intake can suppress gonadotropin levels to a degree that it may interfere with the hormonal cascade required for ovulation.

This finding is a powerful illustration of the dose-dependent nature of nutritional interventions. While a healthy fiber intake is crucial for estrogen balance, an excessive amount may downregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, particularly in sensitive individuals. This underscores the necessity of personalized protocols over generalized recommendations.

Quantitative Impact of Diet on Estrogen Excretion Routes

The choice between a high-fat, low-fiber diet versus a low-fat, high-fiber diet can dramatically alter the primary route of estrogen excretion. Clinical data provides a clear picture of this shift.

| Dietary Pattern | Primary Estrogen Excretion Route | Observed Plasma Estrogen Levels | Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Western” Diet (High Fat, Low Fiber) | Urinary Excretion | Baseline (Higher) | Characterized by lower fecal estrogen excretion, indicating higher enterohepatic recirculation and subsequent renal clearance of metabolites. |

| Vegetarian Diet (Moderate Fat, High Fiber) | Fecal Excretion | 15-20% Lower | Premenopausal women on this diet excreted two to three times more estrogen in their feces compared to those on a Western diet. |

| Asian Immigrant Diet (Very Low Fat, High Fiber) | Fecal Excretion | ~30% Lower | Demonstrates a combined effect of low dietary fat and high fiber intake, leading to even more pronounced reductions in circulating estrogen. |

These findings collectively demonstrate that dietary fiber is not merely a passive bulking agent. It is an active modulator of the gut microbiome, enzymatic activity, and the enterohepatic circulation Meaning ∞ Enterohepatic circulation describes the physiological process where substances secreted by the liver into bile are subsequently reabsorbed by the intestine and returned to the liver via the portal venous system. of estrogens. The quantity and type of fiber consumed can directly influence circulating estradiol concentrations, with downstream effects on the entire endocrine system. This provides a clear, evidence-based rationale for utilizing dietary fiber as a primary tool in the clinical management of hormonal balance.

- Soluble Fiber ∞ This type of fiber, found in oats, barley, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, and some fruits and vegetables, dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance. It is particularly effective at binding to bile acids and conjugated estrogens, directly inhibiting their reabsorption.

- Insoluble Fiber ∞ Found in foods like wheat bran, vegetables, and whole grains, this fiber does not dissolve in water. Its primary role is to add bulk to the stool and speed up the passage of food and waste through the gut, reducing the overall time available for estrogen deconjugation and reabsorption.

- Lignans ∞ These are a class of phytoestrogens found in high concentrations in flaxseeds, sesame seeds, and whole grains. They are metabolized by the gut microbiota into enterolignans, which can modulate the estrogenic activity in the body, providing a balancing effect.

References

- Rose, D. P. et al. “High-fiber diet reduces serum estrogen concentrations in premenopausal women.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 54, no. 3, 1991, pp. 520-5.

- Gaskins, Audrey J. et al. “Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function ∞ the BioCycle Study.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 90, no. 4, 2009, pp. 1061-9.

- Goldin, B. R. et al. “Diet and the excretion and enterohepatic cycling of estrogens.” Cancer, vol. 48, no. S6, 1982, pp. 2164-8.

- Adlercreutz, H. et al. “Effect of dietary components, including lignans and phytoestrogens, on enterohepatic circulation and liver metabolism of estrogens and on sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG).” Journal of steroid biochemistry, vol. 27, no. 4-6, 1987, pp. 1135-44.

- Ervin, S. M. et al. “Gut microbial β-glucuronidases reactivate estrogens as components of the estrobolome that reactivate estrogens.” The Journal of biological chemistry, vol. 294, no. 49, 2019, pp. 18586-99.

- Hu, Shiwan, et al. “Gut microbial beta-glucuronidase ∞ a vital regulator in female estrogen metabolism.” Gut Microbes, vol. 15, no. 1, 2023, 2197592.

- “The Gut-Hormone Connection ∞ How Beta-Glucuronidase Shapes Estrogen Metabolism and Patient Outcomes.” Vibrant Wellness, 2023.

- “The Estrobolome ∞ The Gut Microbiome-Estrogen Connection.” Healthpath, 2025.

- Monroe, Kristine R. et al. “High fiber intake reduces estrogen levels in Latina women.” American Association for Cancer Research Frontiers in Cancer Research Prevention Meeting, 2004.

- Sturgeon, S. R. et al. “The effect of flaxseed supplementation on hormonal levels associated with breast cancer risk.” Cancer Causes & Control, vol. 21, no. 2, 2010, pp. 181-7.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here is a map, not a destination. It details the known pathways and interactions that govern a part of your internal world. Your lived experience ∞ the symptoms you feel, the energy you possess, the rhythm of your cycles ∞ is the terrain this map describes.

The knowledge that you can influence your estradiol levels through something as fundamental as dietary fiber is a powerful form of agency. It shifts the dynamic from one of passive suffering to active participation in your own wellness.

This is not about achieving a perfect diet or adhering to rigid rules. It is about understanding the principles of your own physiology so you can make informed, conscious choices. It is an invitation to begin a dialogue with your body, using food as a form of communication.

What happens when you intentionally increase fiber from whole foods? How does your body respond? This journey of self-study, of connecting clinical science to personal experience, is the foundation of a truly personalized wellness protocol. The goal is to restore function and vitality, allowing you to operate from a place of biological integrity and strength.