Fundamentals

You may feel a persistent fatigue, a frustrating inability to manage your weight, or a general sense of being metabolically out of sync. These experiences are valid, and they often point toward the intricate communication network that governs your body’s energy and function.

Your thyroid, the master regulator of your metabolism, is a central part of this system. Its performance is profoundly connected to another complex world within you ∞ the trillions of microorganisms residing in your gastrointestinal tract. Understanding how your dietary choices directly shape this internal ecosystem is the first step in addressing the root causes of these symptoms and recalibrating your body’s operational baseline.

The connection between your digestive system and your thyroid gland is so intimate that it is known as the gut-thyroid axis. This is a bidirectional communication pathway where the health of one directly influences the other. A significant portion of your thyroid hormone activity depends on processes that occur far from the thyroid gland itself, deep within your intestines.

Your thyroid produces hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4), which is a relatively inactive prohormone. For your body to use it effectively to regulate metabolism, it must be converted into its more potent, active form, triiodothyronine (T3). While some of this conversion happens in the liver, approximately 20 percent of this critical activation step is performed by beneficial bacteria in your gut. The food you consume directly feeds these microbial allies, determining their diversity and their capacity to support your endocrine health.

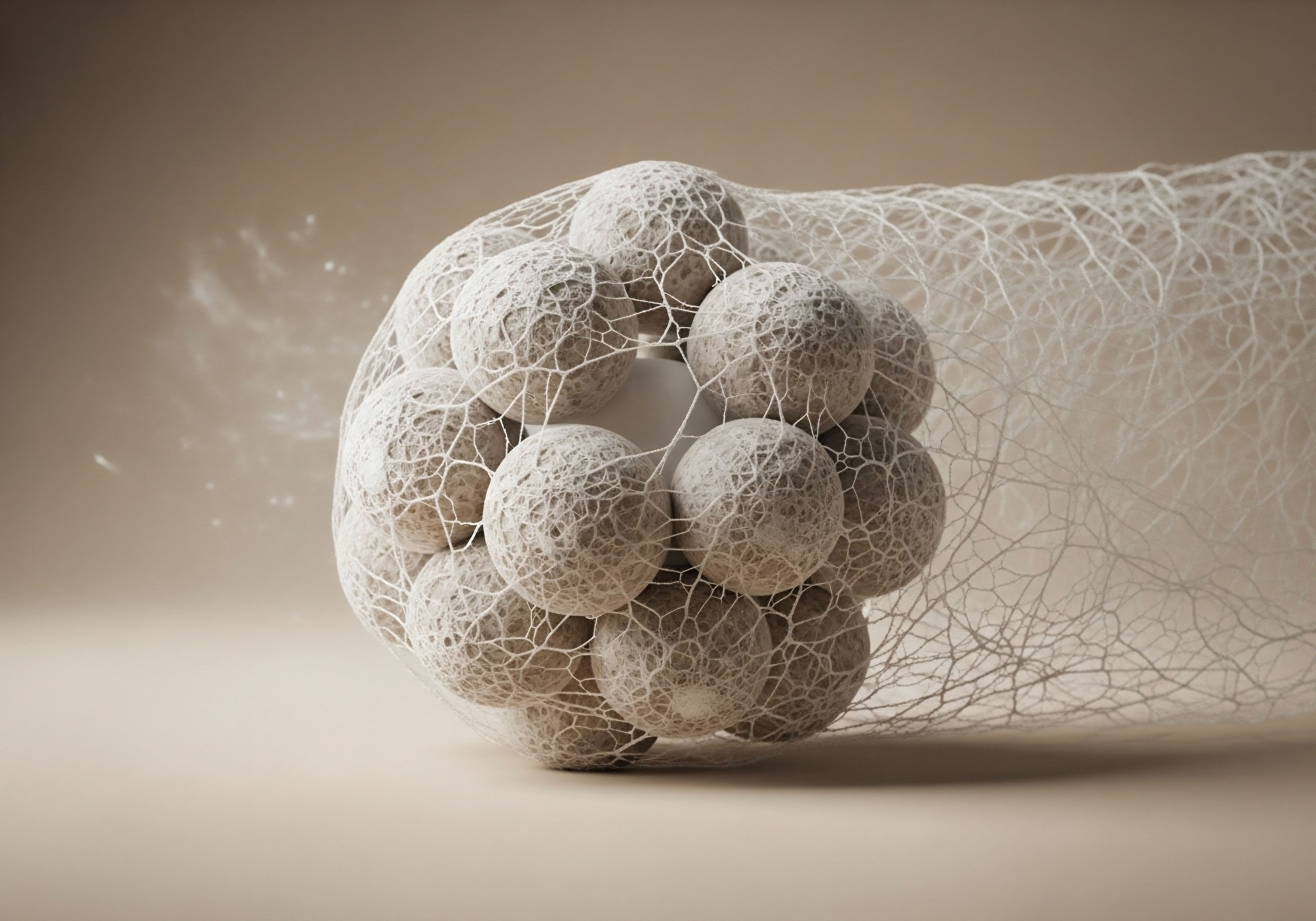

The community of microbes in your gut performs the essential task of activating a significant portion of your thyroid hormones.

The Microbial Workforce and Hormone Activation

Think of your gut microbiome as a dedicated workforce responsible for refining a raw material into a usable product. The thyroid gland produces the raw material, T4, and sends it out. It is the bacteria in your gut that possess the specific enzymatic machinery, such as intestinal sulfatases, required to complete the final stage of manufacturing, yielding the active T3 hormone your cells need to function.

When this microbial workforce is robust and well-nourished, this conversion process is efficient. Your metabolism, body temperature, and energy levels are properly regulated. When the microbiome is compromised, this conversion falters, leaving you with an abundance of the inactive hormone and a deficiency of the active form, even when your thyroid gland itself is producing enough T4.

How Does Diet Shape This Internal Ecosystem?

The composition and health of your gut microbiome are sculpted by your daily dietary inputs. Diets rich in processed foods, sugars, and unhealthy fats can disrupt this delicate balance, favoring the growth of less beneficial microorganisms. This state, known as dysbiosis, impairs the gut’s ability to perform its essential functions, including hormone activation.

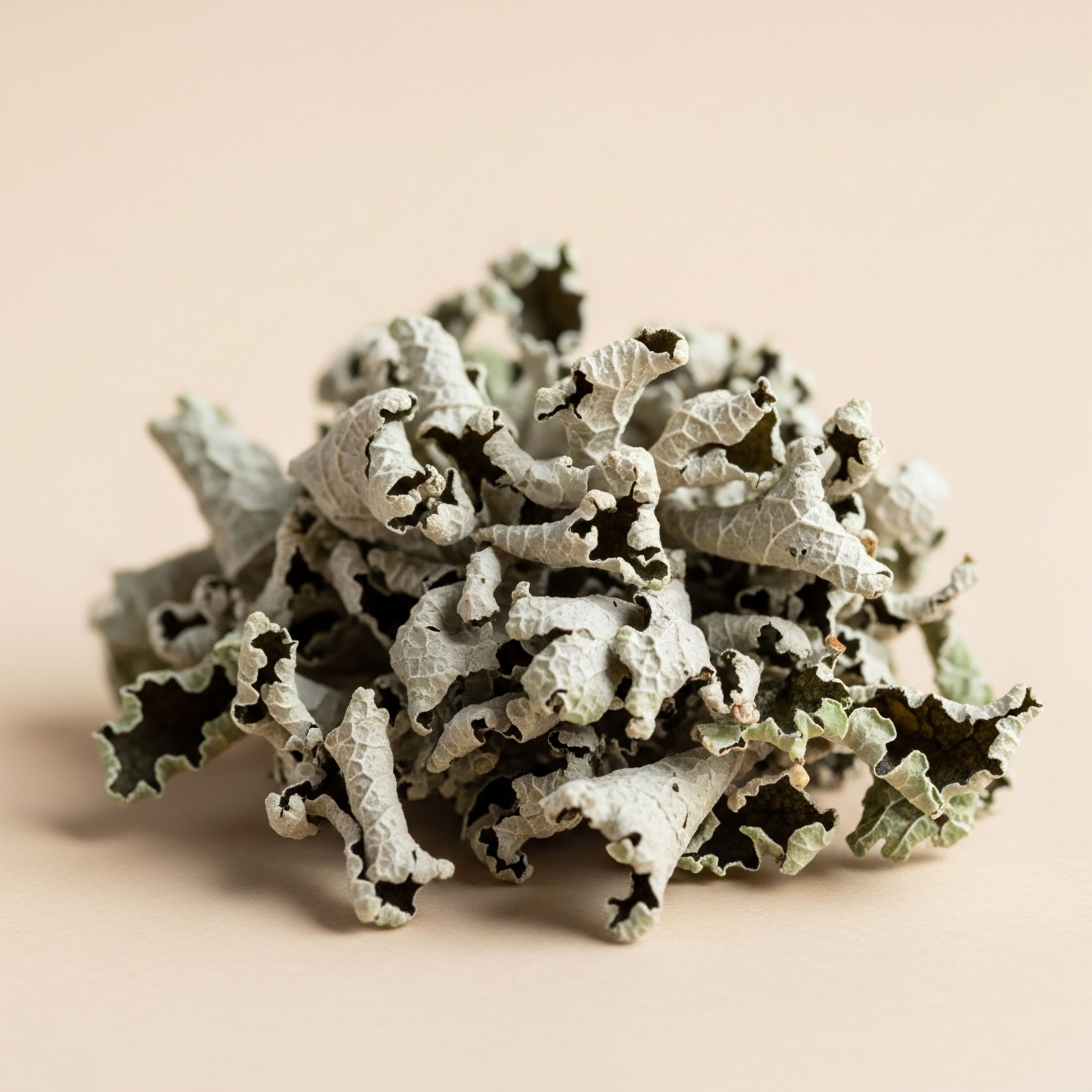

Conversely, a diet centered on whole foods provides the necessary fuel for beneficial bacteria to prosper. These bacteria thrive on specific types of dietary fiber, often called prebiotics. These are non-digestible carbohydrates found in a wide array of plant foods that pass through the upper gastrointestinal tract to nourish the microbes in the colon.

- Prebiotic Fibers ∞ Found in foods like garlic, onions, asparagus, bananas, and whole grains, these fibers are the preferred food for beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium.

- Polyphenols ∞ These compounds, found in berries, dark chocolate, and green tea, also exert a beneficial effect on the gut microbiome, encouraging the growth of health-promoting bacteria.

- Fermented Foods ∞ Items such as yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut introduce beneficial microbes, known as probiotics, directly into your gut, helping to maintain a healthy microbial community.

By making conscious dietary choices, you are directly managing the health and efficiency of the microbial partners that play an indispensable role in your overall hormonal and metabolic wellness. This is a foundational principle of personalized health ∞ recognizing that your daily habits are a form of biological communication with the systems that define your vitality.

Intermediate

A deeper examination of the gut-thyroid axis reveals specific biological mechanisms that your dietary choices directly modulate. The conversion of T4 to T3 is just one piece of a larger, interconnected system involving nutrient absorption, immune regulation, and the integrity of the intestinal barrier.

The food you eat acts as a set of instructions, informing these processes and shaping the very environment in which your hormones function. A state of poor gut health can create a cascade of systemic issues that directly undermine thyroid performance, a reality that positions dietary strategy as a primary tool for endocrine support.

Micronutrient Bioavailability and the Gut

Proper thyroid function depends on a steady supply of specific vitamins and minerals. The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in the absorption and regulation of these essential micronutrients. An imbalanced gut environment can compromise your ability to extract these vital elements from your food, leading to deficiencies that impair thyroid hormone synthesis and metabolism. Your diet must contain these nutrients, and your gut must be healthy enough to absorb them.

Several key micronutrients are at the mercy of this gut-thyroid interplay:

- Iodine ∞ This is the fundamental building block of thyroid hormones. Gut bacteria can influence iodine uptake and utilization.

- Selenium ∞ This mineral is a critical cofactor for the deiodinase enzymes that convert T4 to T3 in both the liver and the gut. Gut microbes can compete with the host for selenium, especially when dietary intake is low, directly impacting hormone activation.

- Zinc ∞ Zinc is also necessary for the synthesis of thyroid hormones and for the function of the T3 receptors on cell nuclei. Its absorption is heavily influenced by gut health.

- Iron ∞ Healthy iron levels are required for the enzyme thyroid peroxidase, which is essential for producing thyroid hormones. Certain gut bacteria can affect iron availability.

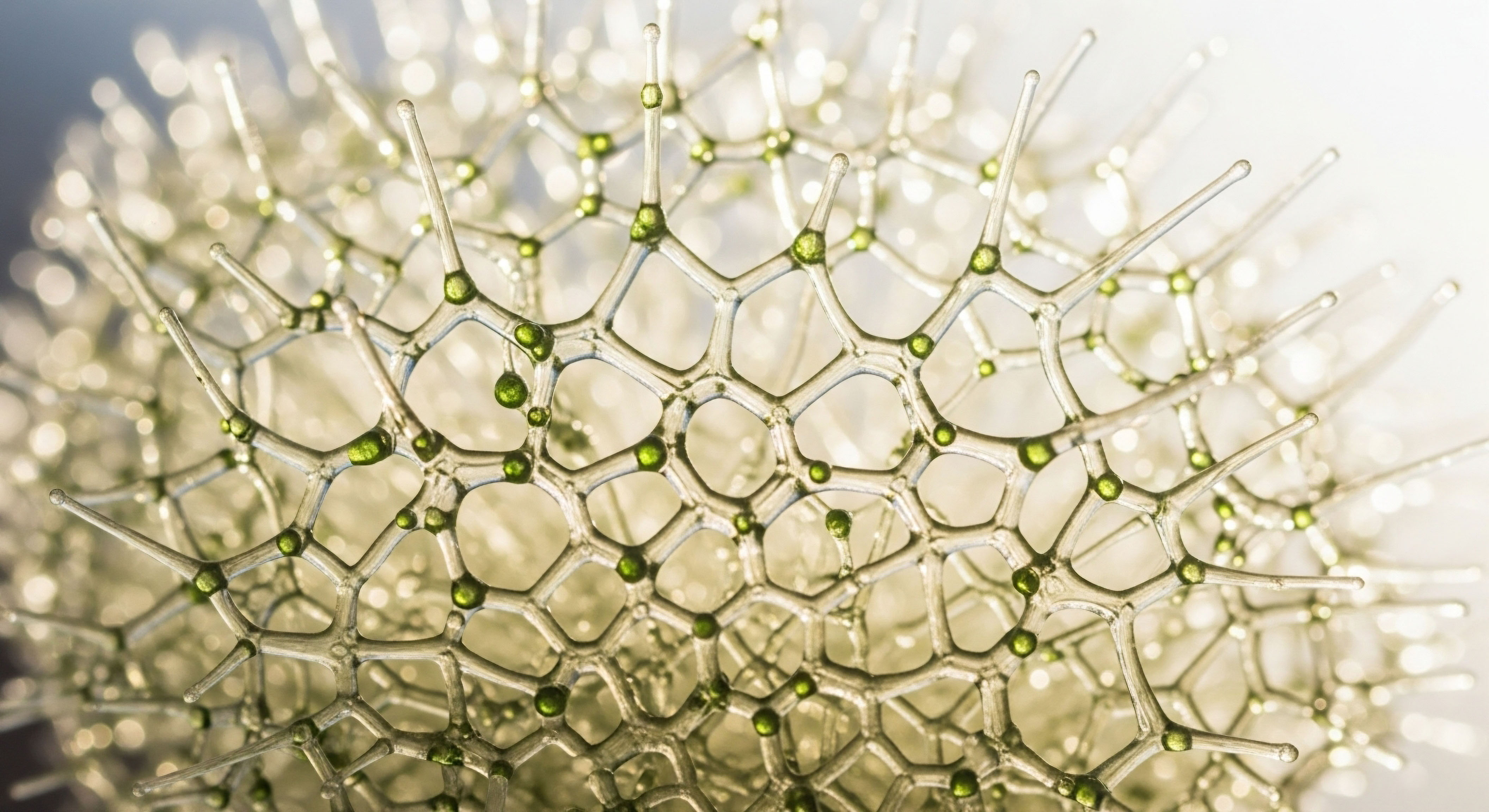

A healthy gut lining ensures the selective absorption of vital nutrients necessary for thyroid hormone production and conversion.

What Is the Role of Intestinal Permeability?

The lining of your intestines is designed to be a selectively permeable barrier. It allows for the absorption of nutrients, water, and electrolytes while preventing toxins, undigested food particles, and pathogens from entering the bloodstream. When the gut microbiome is in a state of dysbiosis, and the intestinal lining becomes damaged, its permeability increases.

This condition is often referred to as “leaky gut.” An overly permeable gut allows antigens to pass into the circulation, triggering a systemic inflammatory response from the immune system. This chronic, low-grade inflammation can disrupt cellular function throughout the body, including the thyroid gland. For individuals with a genetic predisposition, this can be a trigger for autoimmune thyroid conditions like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, where the immune system mistakenly attacks thyroid tissue.

Dietary components play a significant role in maintaining the integrity of this barrier. For example, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which are produced when beneficial gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber, are the primary energy source for the cells lining the colon. A steady supply of butyrate helps keep these cells healthy and the intestinal barrier strong. A diet lacking in fiber starves these bacteria, reduces SCFA production, and can compromise gut integrity over time.

Dietary Protocols for Gut and Thyroid Support

A therapeutic dietary approach aims to accomplish several goals simultaneously ∞ reduce inflammation, seal the intestinal barrier, provide essential micronutrients, and foster a diverse and beneficial microbiome. The table below outlines key dietary components and their specific actions on the gut-thyroid axis.

| Dietary Component | Mechanism of Action | Primary Food Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Prebiotic Fibers | Serve as fuel for beneficial gut bacteria, leading to the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which nourish gut lining cells and support T3 activation. | Jicama, asparagus, onions, garlic, leeks, slightly unripe bananas, plantains. |

| Probiotic Foods | Introduce beneficial live bacteria (e.g. Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) to the gut, helping to restore microbial balance and support immune function. | Yogurt (unsweetened), kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, kombucha, miso. |

| Selenium-Rich Foods | Provide the essential mineral cofactor for the deiodinase enzymes responsible for converting inactive T4 to active T3. | Brazil nuts, sardines, tuna, halibut, turkey, chicken, eggs. |

| Zinc-Rich Foods | Supply a key mineral for thyroid hormone synthesis and cellular receptor function, with absorption dependent on gut health. | Oysters, beef, pumpkin seeds, lentils, chickpeas, cashews. |

| Gluten-Free Grains | For individuals with celiac disease or non-celiac wheat sensitivity, removing gluten can reduce intestinal inflammation and permeability, mitigating autoimmune risk. | Quinoa, brown rice, buckwheat, certified gluten-free oats. |

By implementing these dietary strategies, you are taking a proactive role in managing the complex biological systems that connect your digestive health to your metabolic and hormonal well-being. This is a powerful demonstration of how personalized nutrition can become a cornerstone of long-term vitality.

Academic

A molecular and immunological exploration of the gut-thyroid axis reveals a highly sophisticated system of crosstalk. Dietary choices initiate a cascade of biochemical signals that are interpreted by the gut microbiota, which in turn metabolize these inputs into compounds that directly regulate host endocrine function.

This regulation extends beyond simple T4 to T3 conversion and nutrient absorption, influencing epigenetic expression, immune tolerance, and the metabolism of bile acids, all of which have profound implications for thyroid physiology and pathology, particularly in the context of autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD).

Microbial Metabolites as Endocrine Modulators

The gut microbiota function as a highly active endocrine organ, producing a vast array of metabolites that enter the host circulation and interact with distant cellular targets. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are the main products of bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber and represent a key class of these signaling molecules.

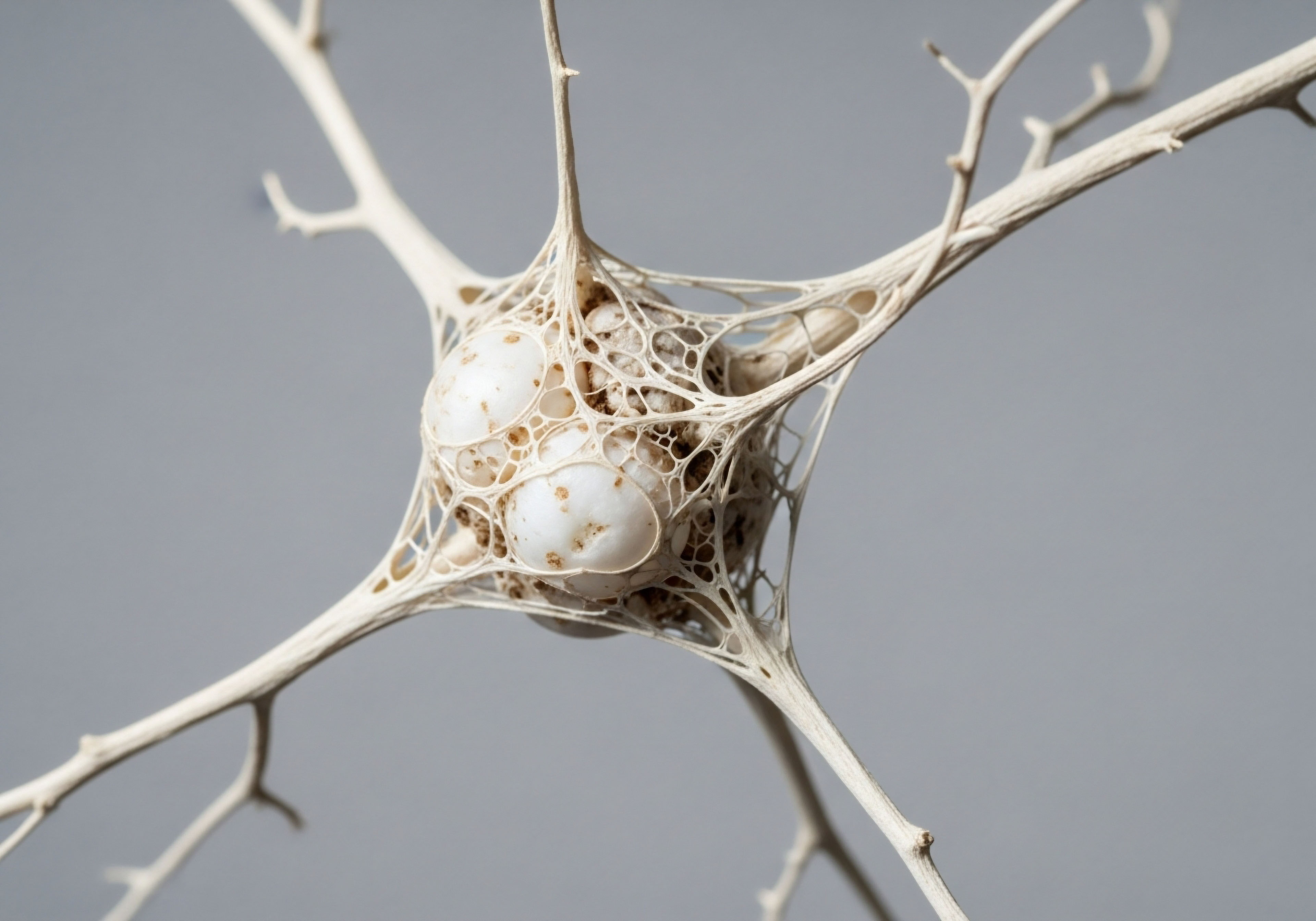

Their influence on thyroid health is multifaceted. Butyrate, for instance, functions as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor. By inhibiting HDACs, butyrate can alter gene expression. This epigenetic modulation has been shown to increase the expression of thyroid hormone receptors on cells, potentially enhancing the body’s sensitivity to available T3. A diet low in fermentable fiber results in lower production of these critical SCFAs, which may contribute to a state of thyroid hormone resistance at the cellular level.

Bacterial byproducts from fiber digestion can epigenetically modify how your cells respond to thyroid hormones.

The Role of Bile Acids and Deiodinase Activity

The connection between gut bacteria and thyroid function is further exemplified by the metabolism of bile acids. Primary bile acids are synthesized in the liver and secreted into the intestine to aid in fat digestion. Gut bacteria then metabolize these into secondary bile acids.

These secondary bile acids have been shown to increase the activity of the enzyme iodothyronine deiodinase, the very enzyme responsible for converting T4 to T3 throughout the body. The composition of the gut microbiota directly determines the profile of secondary bile acids produced, creating another mechanistic link between diet, gut bacteria, and active thyroid hormone levels.

Dietary choices that alter the gut flora, such as high-fat diets, can shift the balance of these bile acids, thereby influencing thyroid hormone economy.

Immune Dysregulation and Molecular Mimicry

The gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) represents the largest single component of the immune system. The constant interaction between the gut microbiota and the GALT is critical for educating the immune system and establishing tolerance. In a state of dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability, this educational process can fail.

This is particularly relevant for autoimmune thyroid diseases like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease. The “molecular mimicry” hypothesis suggests that structural similarities between microbial antigens and host proteins can lead to cross-reactivity.

An immune response mounted against a component of a gut bacterium or a dietary protein that has leaked across the intestinal barrier could mistakenly target structurally similar proteins in the thyroid gland, such as thyroid peroxidase (TPO) or thyroglobulin (Tg), initiating an autoimmune attack. Certain bacterial species have been implicated in this process, and dietary patterns can either promote or suppress their growth, thereby modulating autoimmune risk.

How Can Diet Influence Autoimmune Thyroid Disease?

Specific dietary protocols are being investigated for their potential to modulate the autoimmune response in AITD by acting on the gut. The table below outlines some of these dietary components and their proposed mechanisms from a molecular perspective.

| Dietary Factor | Molecular Mechanism | Clinical Relevance in AITD |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Fiber (Soluble/Insoluble) | Fermented by gut bacteria into SCFAs (e.g. butyrate). Butyrate strengthens tight junctions in the gut lining, reducing intestinal permeability, and promotes the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs), which suppress autoimmunity. | May reduce the antigenic load on the immune system and downregulate the autoimmune attack on the thyroid gland. |

| Polyphenols (e.g. Resveratrol, Curcumin) | Exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. They can modulate gut microbial composition and inhibit pro-inflammatory signaling pathways like NF-κB. | Can help dampen the systemic inflammation that drives autoimmune processes and protect thyroid cells from oxidative stress. |

| Vitamin D | Functions as a steroid hormone that modulates the immune system. It supports the integrity of the intestinal barrier and promotes a tolerogenic immune state. Gut bacteria can influence vitamin D receptor expression. | Deficiency is strongly correlated with AITD. Supplementation, guided by lab testing, may help regulate the immune response. |

| Probiotics (e.g. Lactobacillus reuteri) | Specific probiotic strains can modulate host immune responses. L. reuteri has been shown in animal models to improve thyroid function and reduce inflammation. | Targeted probiotic supplementation may help restore a more balanced gut microbiome and temper autoimmune activity. Human studies are ongoing. |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Precursors to specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), which actively resolve inflammation. They can alter gut microbial diversity and improve the integrity of the gut barrier. | Helps to shift the immune system away from a chronic pro-inflammatory state toward resolution and tissue repair. |

The intricate relationship between dietary molecules, microbial metabolism, and host immunity underscores the profound potential of nutrition as a therapeutic intervention. By viewing food as biological information, we can develop highly personalized strategies to support thyroid function, not just by supplying raw materials, but by modulating the complex signaling networks that govern endocrine health and immune tolerance.

References

- Knezevic, Jovana, et al. “Thyroid-Gut-Axis ∞ How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function?” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 6, 12 June 2020, p. 1769.

- Fröhlich, Eleonore, and Richard Wahl. “Microbiota and Thyroid Interaction in Health and Disease.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 30, no. 8, Aug. 2019, pp. 479-490.

- Virili, Camilla, and Marco Centanni. “‘With a Little Help from My Friends’ ∞ The Role of Microbiota in Thyroid Hormone Metabolism and Action.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 8, Aug. 2015, pp. 2931-2938.

- Kresser, Chris. “Gut Microbes and Your Thyroid ∞ What’s the Connection?” Kresser Institute, 2022.

- “Diets and supplements for thyroid disorders.” British Thyroid Foundation, 2024.

Reflection

A Dialogue with Your Biology

The information presented here offers a new perspective on the symptoms you may be experiencing. It reframes them as communications from a deeply intelligent, interconnected system. The fatigue, the metabolic shifts, the changes in your well-being are signals from a biological network asking for different inputs.

Your daily plate is your most consistent and powerful opportunity to engage in a direct dialogue with your physiology. What is your current dietary pattern communicating to the microbial world within you, and in turn, to your thyroid?

Understanding these mechanisms is the first, most important step. The next is to apply this knowledge through a lens of self-awareness and curiosity. This is the foundation of a truly personalized health strategy, one that moves with you and adapts to your body’s unique needs. The path to reclaiming your vitality begins with the conscious choices you make at every meal, turning the act of eating into an act of profound self-regulation and care.

Glossary

your dietary choices directly

shape this internal ecosystem

gut-thyroid axis

thyroid hormone

gut microbiome

thyroid gland

dietary fiber

prebiotics

probiotics

dietary choices

intestinal barrier

thyroid function

thyroid hormones

deiodinase enzymes

autoimmune thyroid

immune system

short-chain fatty acids

gut microbiota

autoimmune thyroid disease

t4 to t3 conversion

fatty acids

secondary bile acids

bile acids

intestinal permeability