Fundamentals

You feel it in your energy, your mood, your sleep, and your focus. That persistent sense of being slightly out of sync with your own body. This experience, this lived reality of symptoms, is the starting point for understanding your internal world.

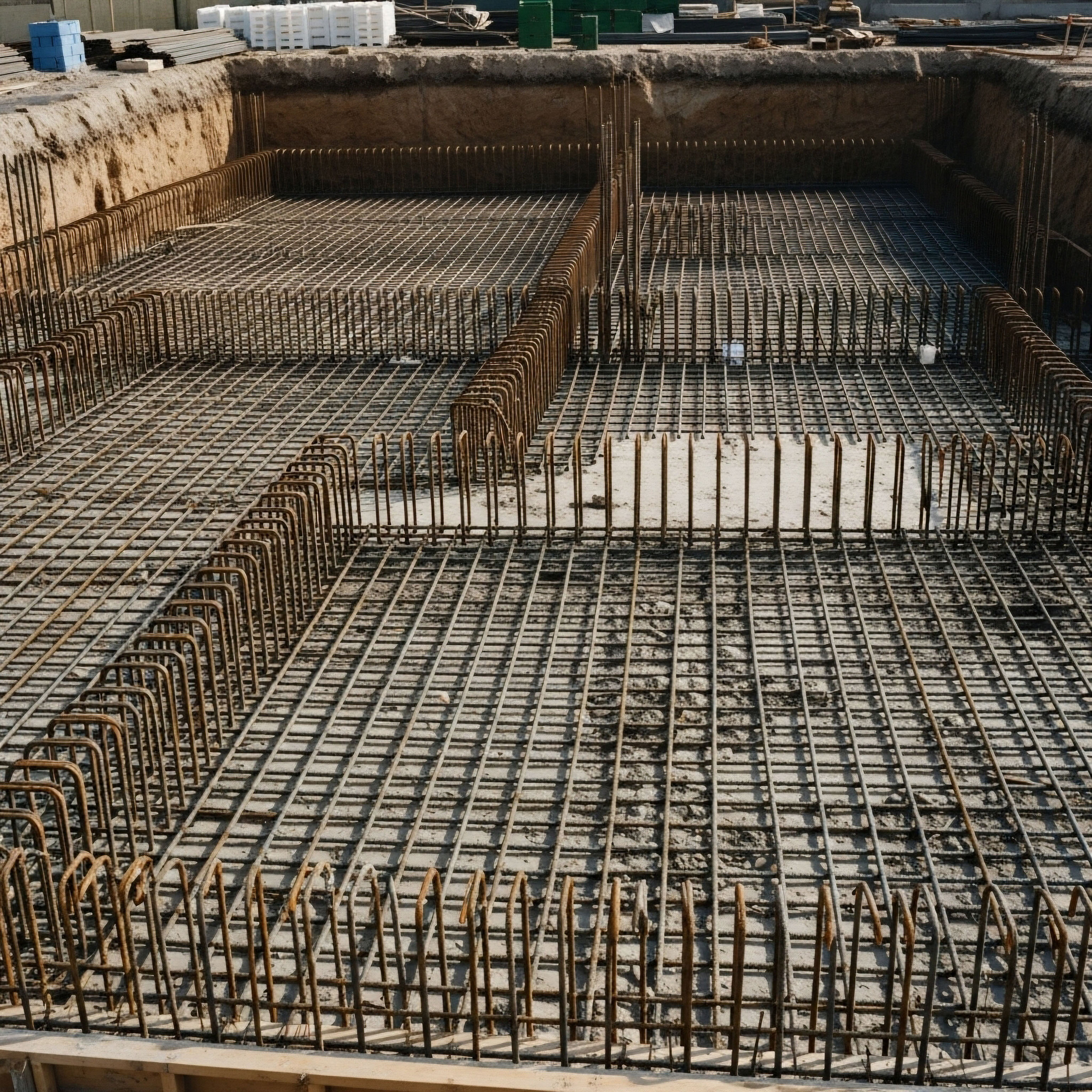

The architecture of your hormonal system, the body’s intricate communication network, is profoundly shaped by the raw materials you provide it every single day. The food on your plate is a set of instructions, sending signals that can either build and balance or disrupt and deplete the very messengers that govern how you function and feel.

Think of your endocrine system as a finely tuned orchestra. Each hormone is an instrument, and for the symphony of health to play in tune, every instrument must have what it needs to perform its part. These needs are met directly through your diet.

The proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals you consume are the literal building blocks for hormones. A deficiency in one area creates a cascade of effects elsewhere. This is why addressing hormonal health begins not with a complex protocol, but with the foundational act of eating. Your dietary choices are the most consistent and powerful tool you have for influencing this internal environment.

Your daily nutritional intake provides the essential chemical instructions that direct your body’s hormonal symphony.

We can begin to connect the dots between what you eat and how you feel by looking at the primary messengers. For instance, sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen are synthesized from cholesterol, a type of fat. Without adequate intake of healthy fats, the production line for these critical hormones slows down.

Similarly, the thyroid hormones that regulate your metabolism are built from the amino acid tyrosine, found in protein, and require minerals like iodine and selenium to function correctly. Your body is a system of interconnected pathways, and the journey to reclaiming vitality starts with supplying these pathways with the precise materials they require to operate as designed.

Intermediate

To truly grasp how dietary choices influence hormonal production, we must move from general concepts to the specific roles of macronutrients. Each meal you consume initiates a complex hormonal response, and the composition of that meal determines the nature of the signals sent throughout your body. Understanding this allows you to strategically use food to support your endocrine system’s balance and efficiency.

The Foundational Roles of Macronutrients

Your body does not see food as “good” or “bad”; it sees chemical constituents to be used for structure and function. Proteins, fats, and carbohydrates are the primary levers through which diet modulates hormonal health. Their balance, quality, and quantity are paramount.

Fats the Precursors to Steroid Hormones

Steroid hormones, including testosterone, estrogens, and cortisol, are all synthesized from cholesterol. A diet chronically low in fat can compromise the structural integrity of cell membranes and limit the substrate available for hormone production. The type of fat is also significant. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in oily fish, have anti-inflammatory properties that can improve cellular sensitivity to hormonal signals. Conversely, diets high in trans fats can promote inflammation, potentially disrupting hormonal balance.

Proteins the Building Blocks of Peptide Hormones

Peptide hormones, such as insulin, growth hormone, and the gut hormones that regulate appetite, are made from amino acids derived from dietary protein. Adequate protein intake is essential for their synthesis. For example, insulin is released in response to both carbohydrates and protein to manage blood glucose.

A balanced intake supports a stable insulin response, which is central to metabolic health. An erratic or insufficient protein supply can impair the body’s ability to produce these critical regulators of metabolism and growth.

How Do Dietary Patterns Affect Hormonal Axes?

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis is the central command line for reproductive health in both men and women. Nutritional status directly informs the hypothalamus, the system’s control center. In states of significant calorie deficit or nutrient deficiency, the hypothalamus may downregulate the production of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This protective mechanism conserves energy but also suppresses the entire reproductive hormone cascade, affecting testosterone and estrogen levels.

Chronic inflammation driven by processed foods can disrupt the sensitive communication lines between your hormones and their target cells.

Insulin regulation is another critical area. Diets high in refined carbohydrates and sugars lead to rapid spikes in blood glucose, demanding a large insulin response. Over time, cells can become less responsive to insulin’s signal, a condition known as insulin resistance.

This state is linked to a host of hormonal disruptions, including elevated estrogen levels and, in women, conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Stabilizing blood sugar through a diet rich in fiber, protein, and healthy fats is a primary strategy for maintaining hormonal equilibrium.

Micronutrients the Essential Cofactors

While macronutrients provide the building blocks, micronutrients are the catalysts that make the reactions happen. Vitamins and minerals are essential cofactors in countless enzymatic processes involved in hormone synthesis, activation, and detoxification.

The table below outlines key micronutrients and their direct roles in supporting the endocrine system. A deficiency in any of these can become a rate-limiting step in a crucial hormonal pathway.

| Micronutrient | Primary Role in Hormonal Health | Common Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Essential for the production of testosterone and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). It also plays a role in insulin sensitivity. | Oysters, beef, pumpkin seeds, lentils |

| Magnesium | Involved in the regulation of the HPA axis (the stress response) and improves insulin sensitivity. Supports sleep quality, which is critical for hormone regulation. | Leafy green vegetables, almonds, avocados, dark chocolate |

| Vitamin D | Functions as a pro-hormone and is linked to testosterone production and insulin regulation. Receptors are found throughout the endocrine system. | Sunlight exposure, fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), fortified milk |

| Selenium | Crucial for the conversion of the inactive thyroid hormone (T4) to the active form (T3). It also has antioxidant properties that protect the thyroid gland. | Brazil nuts, tuna, sardines, eggs |

| Iodine | A fundamental component of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4). Deficiency directly impairs thyroid function. | Seaweed, cod, yogurt, iodized salt |

Academic

The relationship between diet and hormones extends deep into the molecular level, influencing not just hormone synthesis but also their transport, receptor sensitivity, and eventual clearance from the body. A sophisticated understanding of these mechanisms reveals how dietary inputs create systemic effects that can define an individual’s metabolic and hormonal phenotype. We will now examine the intricate interplay between dietary patterns, insulin dynamics, and sex hormone regulation, a nexus of critical importance in clinical practice.

Insulin’s Regulatory Role on Sex Hormone Binding Globulin

Insulin is a primary anabolic hormone, and its role extends far beyond glucose metabolism. It exerts a powerful regulatory influence on the liver’s production of Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG). SHBG is a protein that binds to sex hormones, primarily testosterone and estradiol, in the bloodstream. When a hormone is bound to SHBG, it is biologically inactive and unavailable to bind to its target cell receptor. Therefore, the concentration of SHBG is a major determinant of free, bioavailable hormone levels.

Chronic hyperinsulinemia, often a consequence of a diet high in refined carbohydrates and leading to insulin resistance, has been clinically shown to suppress hepatic SHBG synthesis. The molecular mechanism involves insulin signaling pathways that downregulate the transcription of the SHBG gene. The clinical consequence is a lower level of circulating SHBG.

In this state, a greater fraction of total testosterone and estrogen circulates in its free, active form. This can lead to a state of functional androgen excess in women, a hallmark of PCOS, and altered estrogen-to-androgen ratios in men.

Dietary Fiber and the Gut-Hormone Axis

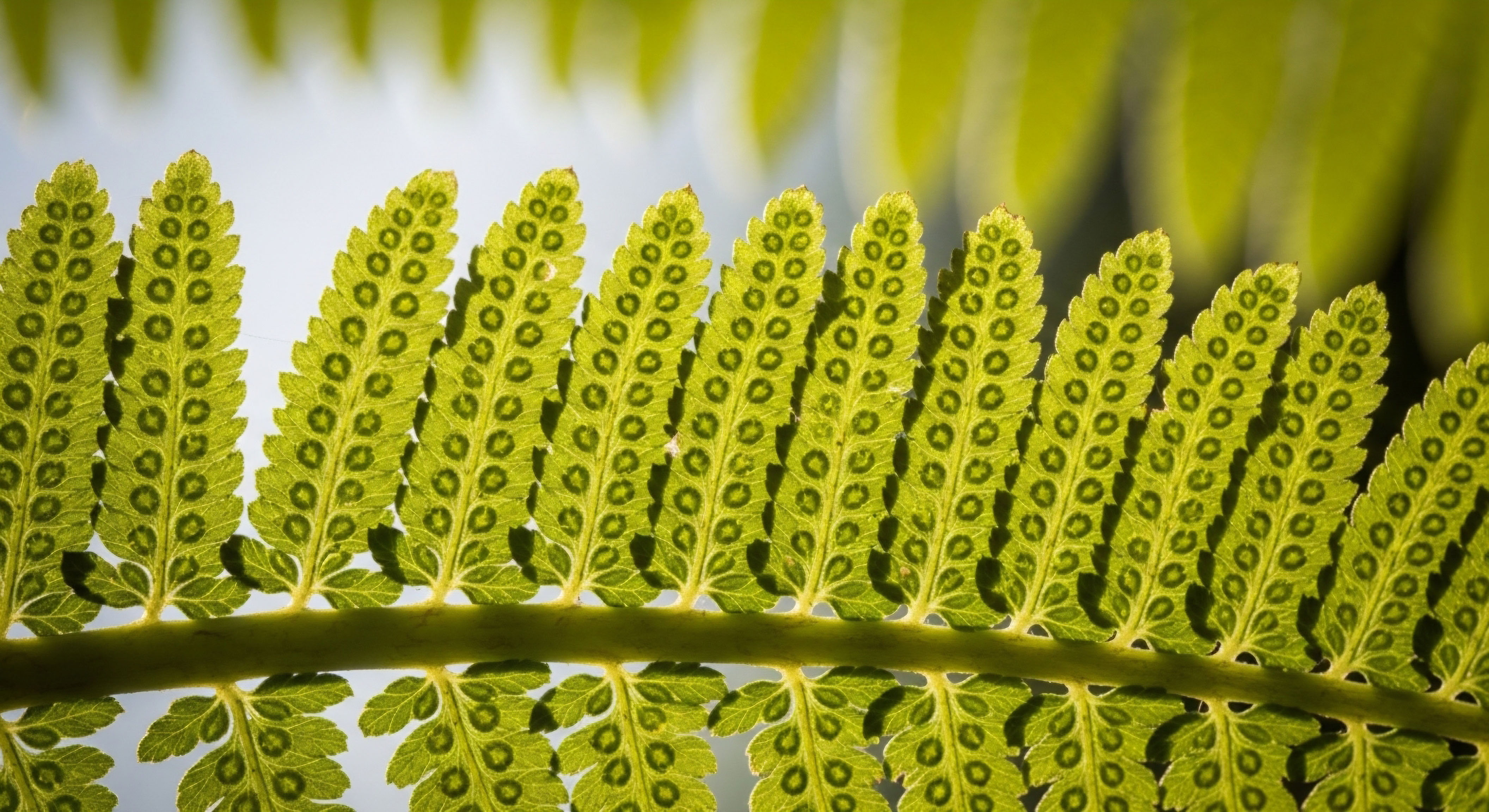

The gut microbiome functions as an endocrine organ in its own right, actively participating in hormone regulation. One of its most critical roles is modulating estrogen metabolism through an enzymatic system known as the “estrobolome.” The estrobolome consists of bacterial genes capable of producing beta-glucuronidase, an enzyme that deconjugates estrogens in the gut.

Estrogens, after being used by the body, are conjugated in the liver to make them water-soluble for excretion. These conjugated estrogens are then transported to the gut. A healthy, diverse microbiome, nourished by a diet rich in complex fibers from vegetables and whole grains, maintains a balanced level of beta-glucuronidase activity.

This allows a certain portion of estrogens to be reabsorbed into circulation, maintaining hormonal homeostasis. However, a dysbiotic microbiome, often resulting from a low-fiber, high-processed-food diet, can lead to either excessive or insufficient beta-glucuronidase activity, disrupting this delicate balance and contributing to conditions of estrogen dominance or deficiency.

The composition of your gut microbiome, which is directly shaped by your diet, actively regulates circulating estrogen levels.

What Are the Implications for Therapeutic Protocols in China?

In the context of China, where dietary patterns are rapidly shifting towards a Western model high in processed foods and refined sugars, the incidence of metabolic and hormonal dysregulation is increasing. For clinicians, this necessitates a therapeutic approach that integrates dietary intervention as a primary modality alongside pharmacological protocols like TRT or peptide therapy.

Understanding the patient’s nutritional baseline becomes a critical diagnostic step. For example, a male patient presenting with symptoms of hypogonadism and low-normal total testosterone but also markers of insulin resistance might have suppressed SHBG. A dietary intervention aimed at improving insulin sensitivity could potentially raise SHBG, optimizing his endogenous hormone profile before initiating exogenous therapy.

The following table details the hormonal impact of two contrasting dietary patterns, illustrating the systemic effects of long-term nutritional choices.

| Hormonal Parameter | Mediterranean-Style Diet | Standard Western Diet |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin Sensitivity | High sensitivity, stable fasting insulin. | Reduced sensitivity, potential for hyperinsulinemia. |

| SHBG Levels | Typically higher, promoting balanced free hormone levels. | Often suppressed, increasing free hormone fractions. |

| Inflammatory Markers (e.g. CRP) | Lower levels due to high intake of polyphenols and omega-3s. | Elevated levels due to high intake of refined sugars and trans fats. |

| Cortisol Levels | Lower fasting cortisol levels have been observed. | Higher cortisol levels may be associated with high sodium and processed food intake. |

| Gut Microbiome Diversity | High diversity, supporting balanced estrogen metabolism. | Low diversity, potentially dysregulating the estrobolome. |

Ultimately, dietary choices are a form of metabolic signaling. Each meal provides a set of instructions that can either support or undermine the body’s intricate hormonal network. A clinical approach that recognizes this fundamental principle can achieve more robust and sustainable outcomes by addressing the root biochemical environment in which hormones operate.

References

- Arnarson, Atli. “How Your Diet Can Affect Your Hormones.” Healthline, 2023.

- Karstens, Sofie. “The Impact of Diet on Hormones.” Balance, 2023.

- Kousar, Shabana. “How does nutrition influence our hormones?” Netdoctor, 2024.

- The Institute for Functional Medicine. “Nutrition and Impacts on Hormone Signaling.” IFM, 2022.

- Silvestris, E. et al. “How the intricate relationship between nutrition and hormonal equilibrium significantly influences endocrine and reproductive health in adolescent girls.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, 2023.

Reflection

You have now seen the profound and direct connection between the molecules in your food and the messengers that govern your internal state. The science provides a map, showing how a single dietary choice can ripple through your entire physiology, influencing your energy, mood, and long-term health. This knowledge is the first, most critical step. It shifts the perspective from being a passive recipient of symptoms to an active participant in your own biology.

The journey to hormonal balance is a personal one. The information presented here is the universal language of biochemistry, but your body has its own unique dialect. Consider your own patterns, your own symptoms, and your own goals. Where do you see the clearest connections?

What small, consistent change could you make that would begin to rewrite the instructions you send to your body each day? The power lies not in a complete overhaul overnight, but in the deliberate, informed choices you make from this point forward. This understanding is your foundation for building a more resilient, vital, and functional self.

Glossary

insulin resistance

dietary patterns

estrogen metabolism

estrobolome