Fundamentals

You have embarked on a path of hormonal optimization, a precise and personal decision to reclaim your body’s vitality. You follow your protocol diligently, yet the results can sometimes feel unpredictable. Some weeks you feel an invigorating sense of clarity and strength, while on others, the familiar fog of fatigue or emotional imbalance returns.

This variability is a common experience, and the explanation for it resides not in the vial or the prescription, but on your plate. Your body is a dynamic biological system, an intricate network of processes where nothing happens in isolation. The therapeutic hormones you introduce are not static agents; they are active molecules that must be metabolized, transported, and utilized. Your dietary choices are the primary directors of this entire metabolic performance.

To truly understand this connection, we must look at three critical interfaces where your nutrition directly interacts with your hormonal therapy. These are the foundational pillars that determine how effectively your body can use the support you are providing it. A grasp of these concepts moves your understanding from simply following a protocol to actively participating in your own biochemical recalibration.

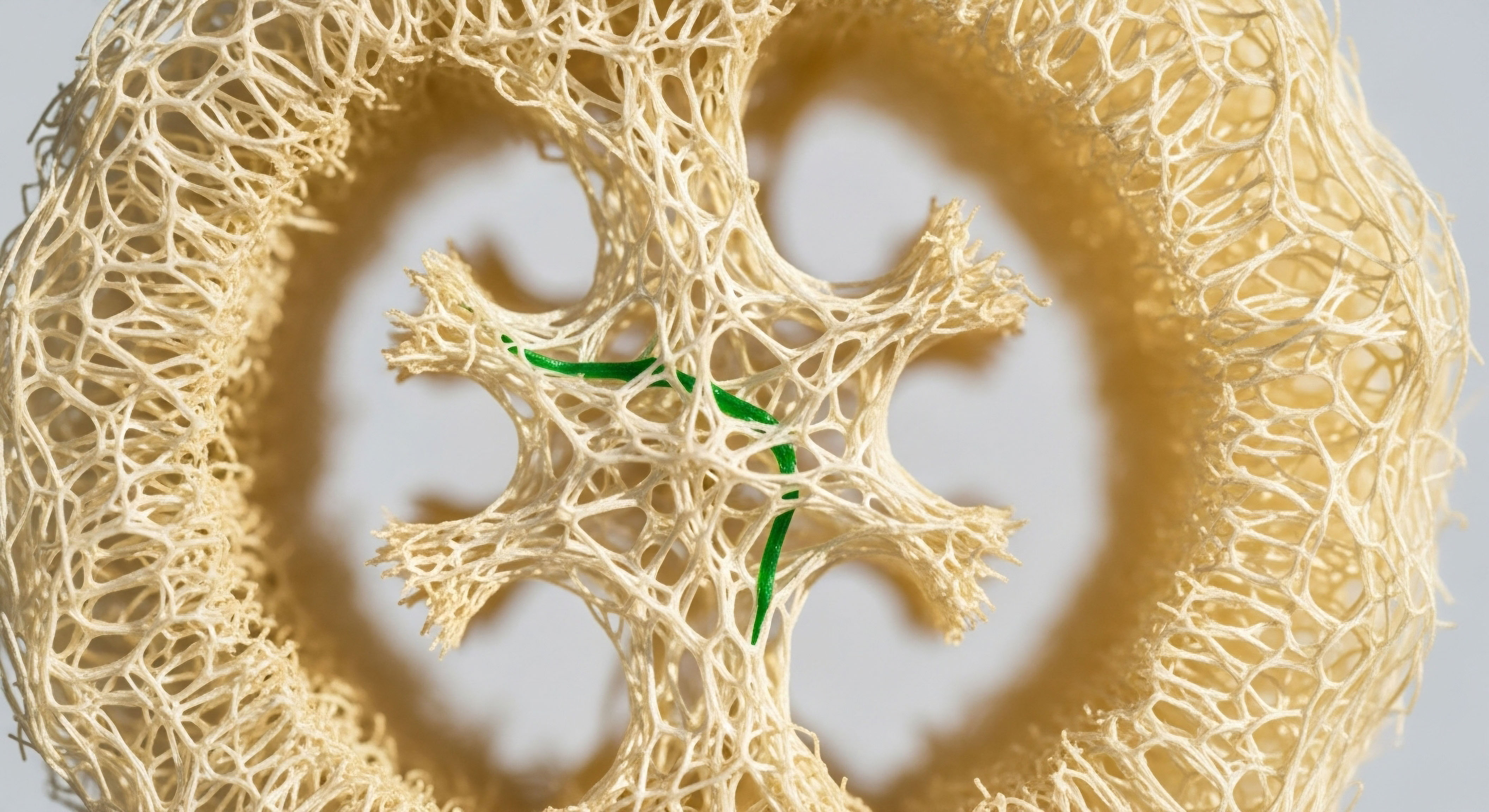

The Liver as the Central Processing Hub

Your liver is the master metabolic clearinghouse of your body. Every substance you ingest, from food and medication to the hormones in your therapy, must pass through it for processing. The liver is equipped with a sophisticated enzymatic system designed to break down compounds, preparing them for use or for safe removal from the body.

When you introduce testosterone or estrogen, your liver’s enzymes get to work, metabolizing these hormones into various forms. The efficiency of these enzymes is directly influenced by the nutrients you provide. A diet lacking in specific proteins or rich in certain compounds can either speed up or slow down this process, fundamentally altering the dose your body actually experiences.

Think of your liver as a highly advanced processing plant; the quality of the raw materials you supply determines the quality and efficiency of its output.

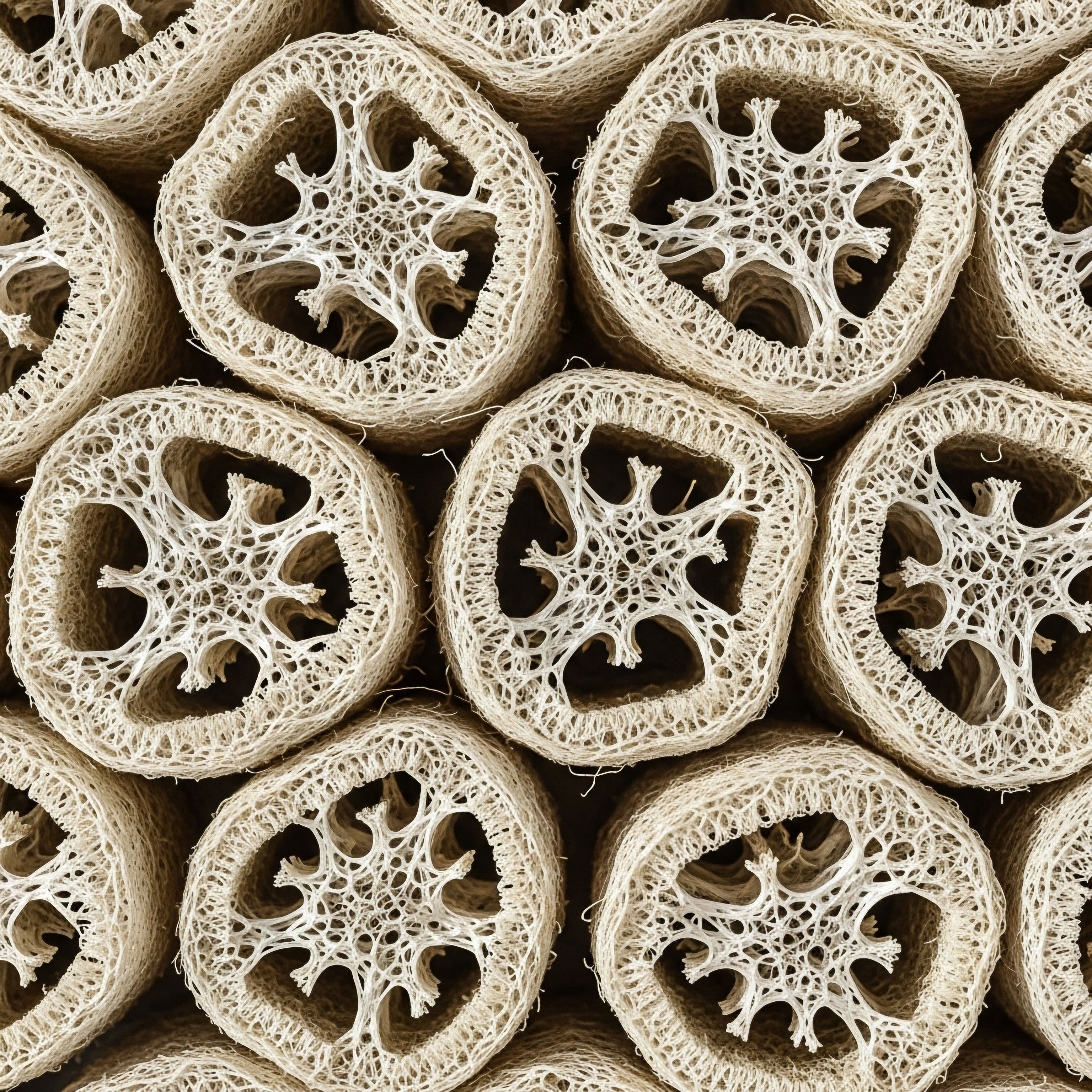

The Gut as the Hormonal Regulator

Your gastrointestinal tract is far more than a simple digestive tube. It is home to a complex ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms known as the gut microbiome. Within this ecosystem exists a specialized collection of bacteria with a profound influence on your hormonal health, particularly estrogen. This sub-community is called the estrobolome.

These bacteria produce enzymes that interact with estrogen that has been processed by the liver and sent to the gut for excretion. Depending on the health and composition of your estrobolome, these gut microbes can either help eliminate old estrogens or reactivate them, sending them back into circulation.

This process of enterohepatic circulation is a critical control point. A well-nourished, balanced microbiome supports healthy estrogen clearance, which is vital for both women on hormonal protocols and for men on testosterone therapy who need to manage estrogen conversion.

Your daily nutritional intake provides the operating instructions for your liver and gut, the two primary organs governing hormone metabolism.

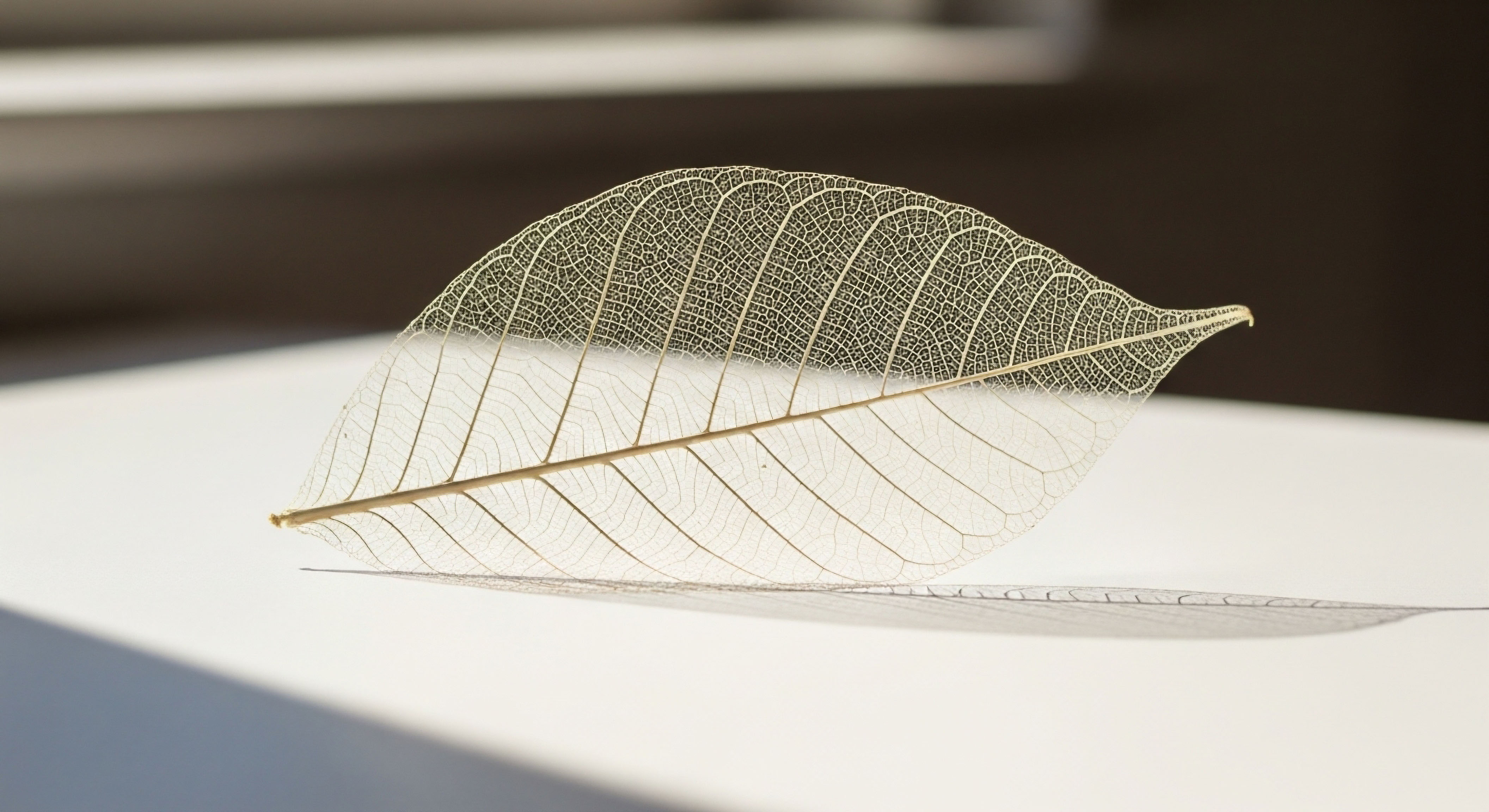

The Bloodstream as the Delivery Network

Once hormones are in your bloodstream, they need a transport system to travel to the target tissues where they will exert their effects. A key transport protein for sex hormones is Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin, or SHBG. You can visualize SHBG as a fleet of molecular taxis that bind to testosterone and estrogen, carrying them safely through the circulation.

Only hormones that are unbound, or “free,” can actively enter cells and do their job. The amount of SHBG your liver produces is heavily dictated by your diet. Certain dietary patterns can increase the number of SHBG taxis, leaving fewer free hormones available to your tissues.

Other food choices can decrease SHBG levels, increasing the amount of active hormone. Therefore, your diet directly modulates the bioavailability of your hormone therapy, influencing how much of the dose is truly active at the cellular level.

Understanding these three interfaces ∞ the liver’s processing power, the gut’s regulatory function, and the bloodstream’s transport system ∞ is the first step in comprehending the powerful role your diet plays. Your food choices are not a passive component of your health; they are an active, ongoing dialogue with your endocrine system. By learning to manage these interactions, you gain a significant measure of control over the outcome of your hormonal journey.

Intermediate

Building upon the foundational understanding that diet governs hormonal therapy, we can now examine the specific biochemical mechanisms at play. The effectiveness of protocols like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for men, or nuanced hormonal support for women, depends on a series of precise metabolic conversions.

Your nutritional habits are a primary modulator of these pathways, capable of either enhancing the therapeutic benefits or creating metabolic obstacles. We will now investigate the machinery of the liver, the chemistry of the gut, and the regulation of transport proteins with greater detail.

The Liver’s Enzymatic Machinery Cytochrome P450

Your liver’s capacity to metabolize hormones is largely dependent on a superfamily of enzymes known as Cytochrome P450 (CYP). These enzymes are responsible for Phase I detoxification, the first step in breaking down a wide array of substances.

For individuals on hormone therapy, the CYP3A4 enzyme is of particular importance, as it is a primary catalyst in the metabolism of testosterone and other steroids. The activity of these enzymes is not fixed; it is adaptable and highly responsive to dietary signals.

Certain foods can induce (speed up) these enzymes, while others can inhibit (slow down) them. This modulation has direct consequences for your hormonal protocol. For instance, accelerated metabolism can clear therapeutic hormones too quickly, reducing their effectiveness. Conversely, inhibited metabolism can cause hormone levels to accumulate, increasing the risk of side effects. A deficiency in dietary protein can also impair CYP enzyme function, as the body lacks the essential amino acids needed to build these critical proteins.

| Nutrient or Food Group | Effect on CYP Enzymes | Clinical Implication for Hormone Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Cruciferous Vegetables (Broccoli, Brussels Sprouts) | Induces (upregulates) certain CYP enzymes, including those involved in estrogen metabolism. | May enhance the clearance of estrogen metabolites, which is beneficial for managing aromatization in men on TRT and for women seeking healthy estrogen balance. |

| Grapefruit and Bergamot | Inhibits CYP3A4 activity. | Can significantly slow the metabolism of testosterone and other steroids, leading to higher-than-intended serum levels and an increased risk of side effects. |

| Unsaturated Fatty Acids (from olive oil, avocados) | Can enhance the expression of certain CYP enzymes in the liver. | Supports the liver’s overall metabolic capacity, promoting efficient processing of hormones. |

| Low Protein Intake | Reduces overall CYP enzyme activity and synthesis. | Impairs the body’s ability to metabolize and clear hormones, potentially leading to unpredictable levels and increased burden on the liver. |

How Do You Optimize Estrogen Clearance?

For many individuals on hormonal protocols, particularly men on TRT, managing estrogen is a central goal. Aromatase is the enzyme that converts testosterone into estradiol, and while some estrogen is necessary for male health, excess levels can lead to unwanted side effects. Diet offers a powerful tool for supporting healthy estrogen metabolism.

Cruciferous vegetables contain unique compounds, namely Indole-3-carbinol (I3C) and its metabolite Diindolylmethane (DIM). These molecules have been shown to shift the metabolism of estrogen away from the potent 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone pathway and toward the weaker 2-hydroxyestrone pathway, promoting a healthier estrogenic balance.

The gut microbiome also plays a directing role. As the liver conjugates (packages up) estrogens for disposal, they are sent into the gut. Certain gut bacteria produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase, which can “unpackage” these estrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed into the body. A diet high in fiber from a variety of plant sources accomplishes two critical tasks:

- Nourishes a healthy microbiome ∞ Fiber feeds beneficial bacteria that help maintain a balanced gut environment, reducing the populations of microbes that produce high levels of beta-glucuronidase.

- Aids in physical excretion ∞ Fiber adds bulk to stool and binds with conjugated estrogens, ensuring they are effectively eliminated from the body rather than being reabsorbed.

Managing Hormone Bioavailability Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin

The amount of “free” hormone available to your tissues is what determines the biological effect of your therapy. Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) is the main protein that binds to testosterone and estradiol in the blood, rendering them inactive until they are released. Therefore, managing SHBG levels is a key strategy for optimizing your protocol. Your diet, and the metabolic state it creates, is a primary driver of SHBG production in the liver.

The interaction between dietary fiber, protein, and carbohydrates directly calibrates SHBG levels, thus controlling the active fraction of your therapeutic hormones.

A diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugars leads to frequent spikes in insulin. Chronically high insulin levels send a signal to the liver to downregulate its production of SHBG. This results in lower total SHBG, which increases the percentage of free testosterone.

While this may seem beneficial, it can accelerate the conversion of testosterone to estrogen and lead to a more rapid clearance of the hormone, causing peaks and troughs. Conversely, a diet rich in fiber has been shown to be positively associated with higher SHBG levels. Adequate protein intake is also essential, as very low protein diets can lead to an undesirable elevation in SHBG, potentially reducing the bioavailable hormone to suboptimal levels.

| Dietary Factor | Impact on SHBG Production | Consequence for Free Hormone Levels |

|---|---|---|

| High Sugar / High Glycemic Load Diet | Suppresses liver production of SHBG due to high insulin levels. | Decreases SHBG, leading to higher levels of free testosterone and estradiol. This can increase aromatization and other side effects. |

| High Fiber Diet | Positively correlated with higher SHBG concentrations. | Increases SHBG, leading to lower levels of free hormones. This can create a more stable hormonal environment with less fluctuation. |

| Low Protein Diet | Associated with elevated SHBG levels. | Increases SHBG, potentially reducing the bioavailable fraction of testosterone to below the therapeutic target. |

| Moderate to High Protein Diet | Negatively correlated with SHBG, helping to maintain it in a healthy range. | Helps to balance SHBG levels, ensuring an adequate supply of bioavailable hormone without excessive spikes. |

Academic

An academic exploration of the intersection between nutrition and hormone therapy metabolism requires a systems-biology perspective. The efficacy and safety of hormonal optimization protocols are governed by a complex interplay between the endocrine system, metabolic pathways, and the body’s detoxification architecture.

The administered hormone is merely an input; the physiological outcome is dictated by a network of feedback loops that are profoundly influenced by an individual’s metabolic phenotype, which is itself shaped by long-term dietary patterns. We will now analyze the integrated axes that connect insulin dynamics, hepatic function, and gut-mediated inflammation to the pharmacokinetics of hormone replacement.

The Insulin-SHBG-Hormone Axis a Central Regulatory Loop

The relationship between insulin sensitivity and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) represents a critical control point in sex hormone physiology. Chronic hyperinsulinemia, a state driven by diets high in processed carbohydrates and sugars, is a potent suppressor of hepatic SHBG synthesis. This occurs at the transcriptional level within the hepatocyte.

Elevated insulin signaling inhibits the transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-alpha (HNF-4α), a key promoter of the SHBG gene. The clinical consequence of this suppression is a decrease in circulating SHBG concentrations.

For a male patient on a standard TRT protocol (e.g. weekly Testosterone Cypionate), diet-induced low SHBG creates a challenging clinical picture. The lower binding capacity leads to a supraphysiological spike in free testosterone immediately following an injection.

This elevated free fraction provides a larger substrate pool for the aromatase enzyme, potentially accelerating the conversion to estradiol and necessitating higher or more frequent doses of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole. Furthermore, the higher free fraction of testosterone is cleared more rapidly from circulation, leading to a shorter terminal half-life and more significant troughs toward the end of the dosing cycle.

This volatility can manifest as clinical instability. Therefore, a primary therapeutic target for optimizing TRT is the improvement of insulin sensitivity through nutritional interventions, such as low-glycemic-load diets, which upregulate SHBG production and create a more stable and predictable pharmacokinetic profile.

What Is the Link between Gut Permeability and Systemic Inflammation?

The gut microbiome’s influence extends beyond the local metabolism of estrogens via the estrobolome. A state of gut dysbiosis, often precipitated by a low-fiber, high-sugar Western diet, can compromise the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier. This leads to increased intestinal permeability, a condition where bacterial components like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can translocate from the gut lumen into systemic circulation.

This translocation of LPS is a powerful trigger for the innate immune system, leading to a state of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation.

This inflammatory state has profound implications for hormone therapy. Systemic inflammation can directly interfere with hormonal signaling at the receptor level, inducing a form of hormone resistance. Inflammatory cytokines can also disrupt the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, affecting endogenous hormone production and the body’s response to exogenous therapy.

For example, inflammation can suppress the hepatic synthesis of key proteins, including SHBG, further compounding the issues driven by hyperinsulinemia. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle where a poor diet drives dysbiosis, which causes inflammation, which in turn disrupts metabolic and endocrine function, ultimately impairing the body’s ability to effectively utilize hormone therapy. Advanced nutritional strategies are required to break this cycle.

- Polyphenol-Rich Foods ∞ Consumption of foods rich in polyphenols (e.g. berries, dark chocolate, green tea) can modulate the gut microbiome, promoting the growth of beneficial species and enhancing gut barrier integrity.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids ∞ Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are precursors to specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), which actively resolve inflammation, counteracting the effects of LPS-induced inflammation.

- Targeted Prebiotics and Probiotics ∞ The use of specific prebiotic fibers (e.g. inulin, FOS) and probiotic strains (e.g. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species) can help restore a healthy gut microbial composition, reduce beta-glucuronidase activity, and improve gut barrier function.

Systemic health, rooted in metabolic efficiency and low inflammation, is the platform upon which successful hormonal optimization is built.

Pharmacogenomics and Diet a Look to the Future

The next frontier in personalizing hormone therapy lies in understanding the interplay between an individual’s genetic makeup, their diet, and their response to treatment. Genetic polymorphisms in the Cytochrome P450 enzyme family are common and can significantly alter the rate at which an individual metabolizes hormones.

For example, a person with a polymorphism that results in “slow” CYP3A4 activity will clear testosterone more slowly than someone with a “normal” or “fast” phenotype. If this individual consumes foods that further inhibit CYP3A4, such as grapefruit, they risk accumulating toxic levels of the hormone.

Conversely, a “rapid metabolizer” might find their therapeutic dose is cleared too quickly to be effective, a situation that could be exacerbated by a diet rich in CYP-inducing compounds. The potential exists to develop dietary protocols tailored to an individual’s pharmacogenomic profile, using nutrition as a tool to normalize metabolism and achieve a more stable and effective therapeutic window. This approach would represent a true synthesis of personalized medicine, integrating genomics, endocrinology, and clinical nutrition.

References

- Longcope, C. et al. “Diet and sex hormone-binding globulin.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 85, no. 1, 2000, pp. 293-296.

- Fowke, J. H. et al. “Brassica vegetable consumption shifts estrogen metabolism in healthy postmenopausal women.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, vol. 9, no. 8, 2000, pp. 773-779.

- Kwa M, Plottel CS, Blaser MJ, Adams S. “The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor ∞ Positive Female Breast Cancer.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 8, 2016.

- Baker, J. M. et al. “Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

- Zendehdel, M. and M. Z. Nouno. “Human cytochrome P450 enzymes and drug metabolism in humans.” Journal of Biosciences and Medicines, vol. 9, no. 12, 2021, pp. 77-99.

- Salama, A. A. et al. “Effects of Hormone Replacement Therapy on Insulin Resistance in Postmenopausal Diabetic Women.” Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, vol. 4, no. 1, 2016, pp. 93-97.

- Simos, G. et al. “Relation of Dietary Carbohydrates Intake to Circulating Sex Hormone-binding Globulin Levels in Postmenopausal Women.” The FASEB Journal, vol. 30, no. S1, 2016.

- Dorgan, J. F. et al. “Effects of dietary fat and fiber on plasma and urine androgens and estrogens in men ∞ a controlled feeding study.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 64, no. 6, 1996, pp. 850-855.

- Kopylchuk, H. P. et al. “Effect of Dietary Protein Deficiency on the Activity of Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Systems in the Liver of Rats of Reproductive Age Under Acetaminophen-Induced Injury.” Acta Scientific Gastrointestinal Disorders, vol. 5, no. 4, 2022, pp. 39-48.

- The Marion Gluck Clinic. “Hormones & Gut Health ∞ The Estrobolome & Hormone Balance.” 2022.

Reflection

A New Lens for Your Health

You now possess a deeper map of your own internal biology. The information presented here connects the sensations you feel in your body to the complex, silent biochemical processes occurring within. It shifts the perspective from being a passive recipient of a therapy to an active collaborator with it. With this knowledge, the daily act of eating transforms. It becomes a conscious opportunity to support the very foundation upon which your hormonal health is built.

What Questions Arise Now?

As you stand before your pantry or walk through the grocery store, what new considerations come to mind? How does the concept of feeding your microbiome change your view of fiber? When you feel a dip in energy, might you now consider the interplay of your last meal with your SHBG levels, rather than simply the timing of your protocol?

This knowledge is not a set of rigid rules. It is a new lens through which to observe your body’s unique responses, empowering you to make more precise and personalized adjustments. Your journey toward optimal function is a dynamic one, and you are now better equipped to navigate it with intention and insight.

Glossary

estrobolome

enterohepatic circulation

sex hormone-binding globulin

hormone therapy

shbg levels

phase i detoxification

cytochrome p450

side effects

beta-glucuronidase

metabolic pathways

insulin sensitivity