Fundamentals

Beginning a protocol with semaglutide often introduces a new set of physical sensations. You might notice a feeling of fullness that arrives much sooner than you are used to, or a subtle, persistent sense of nausea that clouds your day. These experiences are the first signs of a profound biological conversation starting within your body.

This medication is initiating a process of metabolic recalibration, and your dietary choices are the most powerful tool you have to guide this dialogue, ensuring it leads to restored vitality instead of discomfort. Understanding the ‘why’ behind these feelings is the first step in transforming your relationship with food from a source of potential side effects into a foundational pillar of your success.

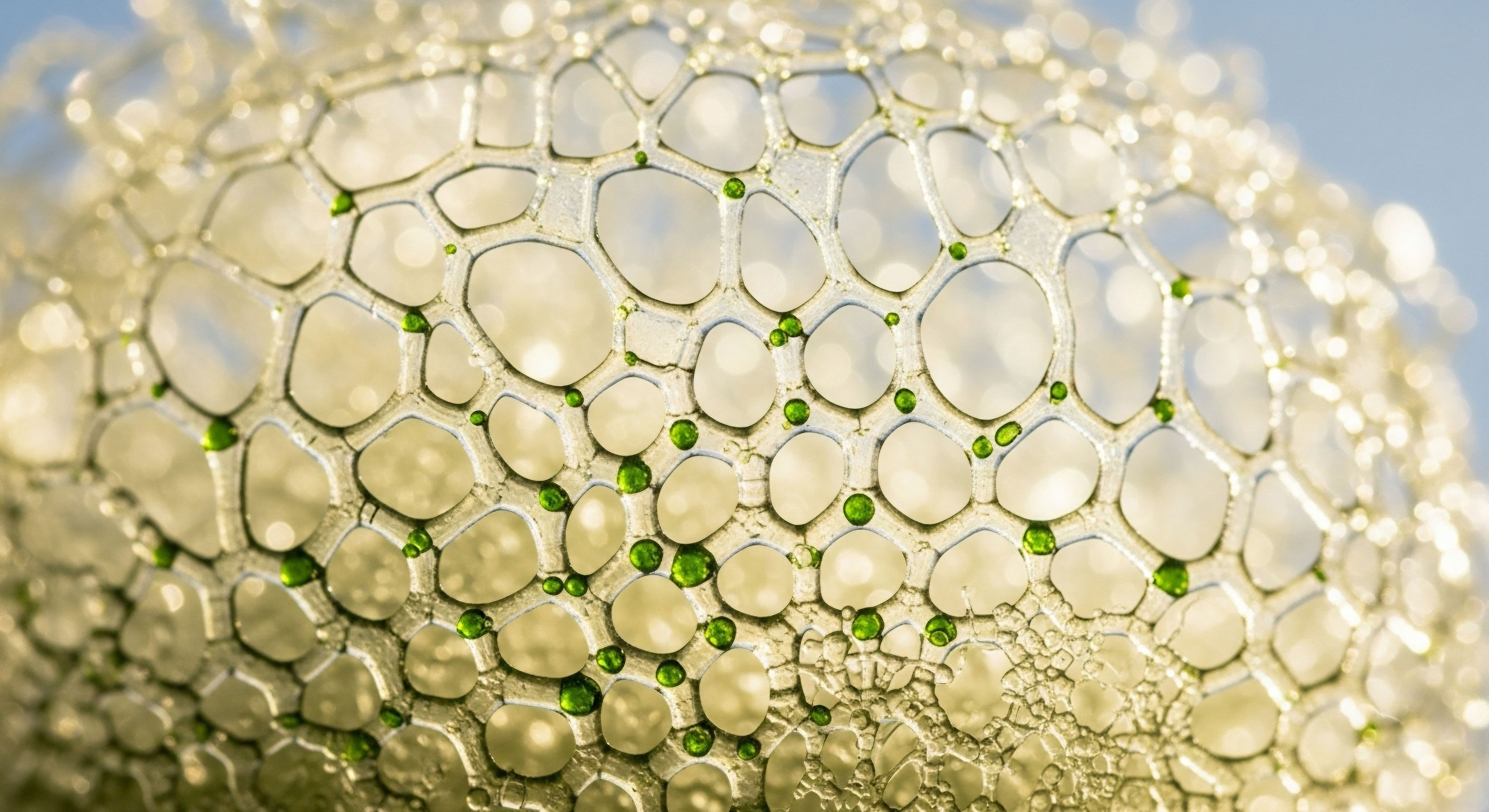

Semaglutide functions by mimicking a natural hormone called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Your body typically releases GLP-1 after a meal, where it performs two primary jobs. It signals to your brain’s control center, the hypothalamus, that you are full, reducing the drive to continue eating.

Concurrently, it instructs your stomach to slow down its process of emptying. This dual action is central to the therapeutic effect. The food you consume remains in your stomach for a longer duration, which contributes mechanically to the sensation of satiety and helps stabilize the release of glucose into your bloodstream. This deliberate slowing of your digestive pace is the key to its efficacy and also the source of most common side effects.

The primary function of semaglutide involves slowing gastric emptying, which directly impacts how your body processes the foods you eat.

This medication-induced delay in digestion means that certain foods become challenging for your system to manage. Foods high in fat, such as fried items, heavy creams, or rich cuts of meat, are already complex and slow for the body to break down.

When you add the braking effect of semaglutide, these foods can linger in the stomach for an extended period, fermenting and causing significant discomfort, bloating, acid reflux, and nausea. Similarly, large, dense meals can overwhelm a digestive system that is operating at a more deliberate pace. Your body is communicating a new set of rules for operation; learning to work with them is essential.

Foundational Dietary Adjustments

Adapting to semaglutide begins with modifying the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of eating. The initial goal is to minimize gastrointestinal stress and allow your body to acclimate to the medication’s presence. This involves a conscious shift toward smaller, more frequent meals.

Eating five or six small meals throughout the day, rather than three large ones, prevents the stomach from becoming overfilled and reduces the likelihood of discomfort. Eating slowly and chewing thoroughly pre-digests food and lessens the burden on your stomach. Hydration is also a key component. Sipping clear, unsweetened fluids like water, broth, or herbal tea throughout the day helps maintain hydration without adding volume to the stomach.

Foods to Prioritize and Foods to Approach with Caution

During the initial phase of treatment, your diet should center on foods that are gentle on the digestive system. These choices help provide necessary nutrition without exacerbating side effects.

- Lean Proteins ∞ Skinless chicken or turkey, white fish, tofu, and legumes are excellent sources of protein that are typically easier to digest than fatty meats.

- Well-Cooked Vegetables ∞ Steamed or roasted non-starchy vegetables like carrots, green beans, and spinach provide essential nutrients without adding excessive bulk.

- Simple Carbohydrates ∞ Small portions of rice, toast, or crackers can be calming for the stomach and help alleviate feelings of nausea.

- Water-Rich Foods ∞ Broth-based soups and foods like cucumbers and melons contribute to hydration and are generally well-tolerated.

Conversely, certain foods are known to trigger or worsen side effects. It is wise to limit or avoid these items, especially as your body adjusts.

- High-Fat and Greasy Foods ∞ French fries, pizza, fatty cuts of red meat, and creamy sauces are notoriously difficult to digest and are common culprits for nausea and bloating.

- Sugary Foods and Beverages ∞ Sodas, candies, and pastries can cause rapid fluctuations in blood sugar and may contribute to nausea.

- Spicy Foods ∞ Highly spiced dishes can irritate the stomach lining, leading to heartburn and discomfort.

- Alcohol ∞ Alcoholic beverages can irritate the gastrointestinal tract and interfere with blood sugar regulation, complicating the adjustment period.

Intermediate

Once your body has acclimated to the initial presence of semaglutide and the most acute side effects have subsided, the dietary focus can evolve. The objective shifts from simply managing discomfort to strategically optimizing the medication’s profound metabolic benefits.

This is where you begin to use nutrition as a sophisticated instrument to enhance insulin sensitivity, preserve metabolically active tissue, and direct your body composition towards a healthier state. Your plate becomes a control panel for fine-tuning your physiology. Each macronutrient ∞ protein, fat, and carbohydrate ∞ plays a distinct role in this process, and understanding how to deploy them creates a powerful synergy with your therapeutic protocol.

What Is the Role of Protein in a Semaglutide Protocol?

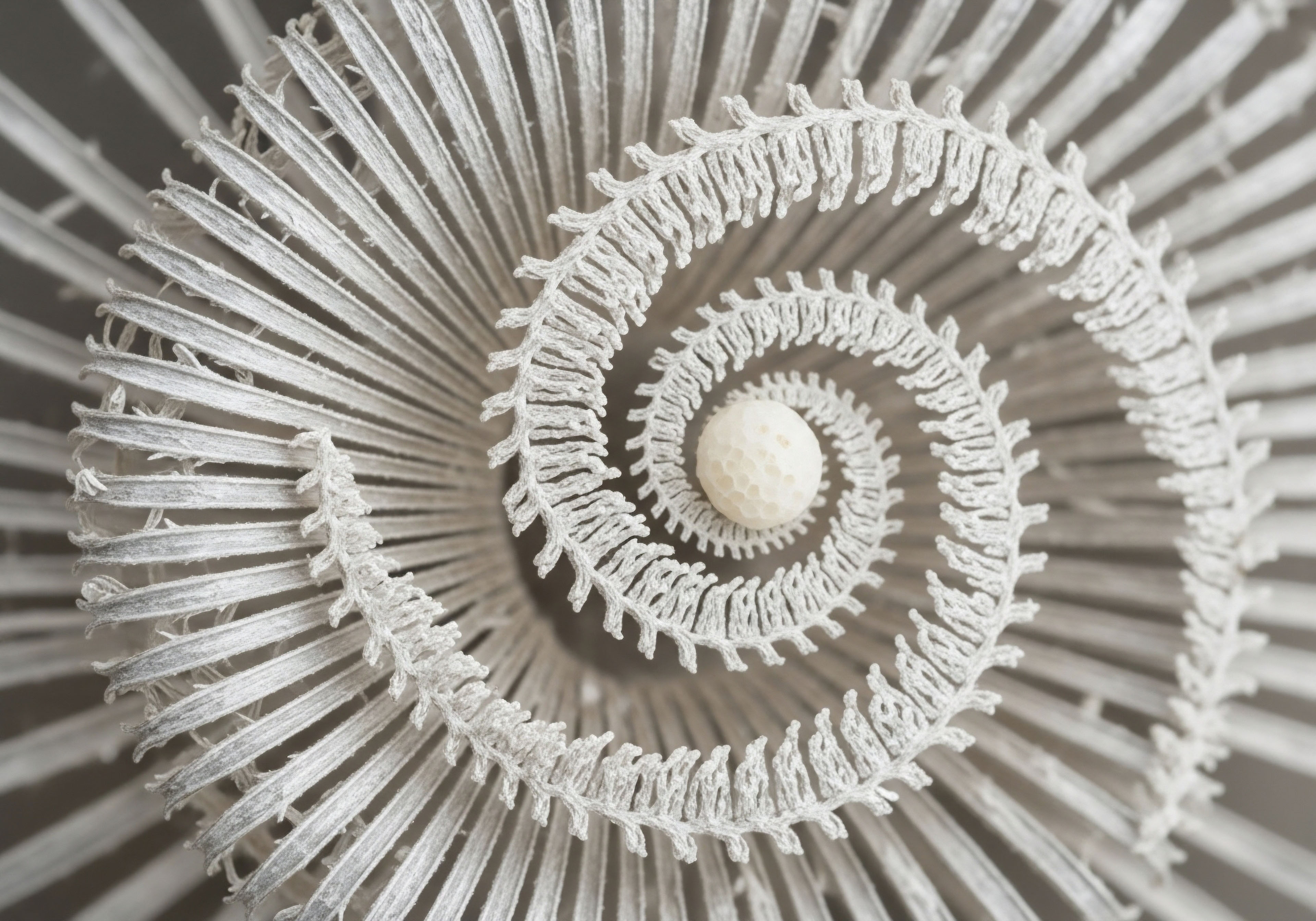

A significant consideration during weight loss spurred by GLP-1 agonists is the preservation of lean muscle mass. Rapid weight loss can often result in the loss of both fat and muscle tissue. Muscle is a metabolically expensive tissue; it burns calories at rest and is a primary site for glucose disposal, making it a vital ally in improving insulin sensitivity.

Losing muscle can lower your resting metabolic rate, making long-term weight maintenance more challenging. A recent study highlighted that certain individuals may be more susceptible to muscle loss while using semaglutide, and that a higher protein intake could be a protective countermeasure. Therefore, ensuring adequate protein consumption is a clinical necessity for anyone on this therapy.

The goal is to supply your body with a steady stream of amino acids, the building blocks of muscle tissue. This helps signal to your body that muscle should be preserved while fat is mobilized for energy. Aiming for a consistent intake of high-quality protein throughout the day is an effective strategy. This involves including a protein source with every meal and snack. This approach supports muscle protein synthesis and also enhances satiety, complementing semaglutide’s appetite-suppressing effects.

Prioritizing protein intake is a critical strategy to help preserve lean muscle mass, which is essential for maintaining long-term metabolic health.

| Protein Category | Well-Tolerated Options | Notes for Semaglutide Users |

|---|---|---|

| Lean Poultry | Skinless chicken breast, turkey breast | Baking, grilling, or poaching is preferable to frying. Avoid heavy sauces or marinades. |

| Fish | Cod, tilapia, haddock, salmon, tuna | White fish are often easier to digest. Salmon provides beneficial omega-3 fats. |

| Plant-Based | Lentils, chickpeas, tofu, edamame | These offer fiber; introduce them gradually to assess digestive tolerance. |

| Dairy & Eggs | Greek yogurt (plain), cottage cheese, eggs | Full-fat dairy can be problematic for some. Eggs should be boiled or poached. |

Fine-Tuning Carbohydrate and Fat Intake

With protein established as the foundation, the next step is to strategically manage carbohydrates and fats. The quality of these macronutrients is paramount. For carbohydrates, the focus should be on low-glycemic, high-fiber sources. These are foods that release glucose into the bloodstream slowly and steadily, preventing the sharp spikes and crashes that can disrupt energy levels and hunger signals.

This aligns perfectly with semaglutide’s function of improving glycemic control. Good choices include whole grains like quinoa and oats, non-starchy vegetables, and legumes. These foods also provide prebiotic fibers that nourish a healthy gut microbiome, which is integral to overall metabolic function.

When it comes to dietary fats, the distinction between different types is important. While heavy, greasy, and fried foods rich in saturated and trans fats are known to worsen gastrointestinal side effects, healthy fats are essential for hormone production and overall health.

Sources of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, such as avocado, nuts, seeds, and olive oil, should be included in the diet in moderation. Consuming them in small quantities, spread throughout the day, is less likely to trigger the digestive distress associated with large, high-fat meals. For instance, a small handful of almonds or a quarter of an avocado can provide essential fatty acids without overwhelming the digestive system.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of semaglutide tolerance requires moving beyond simple dietary recommendations and examining the intricate interplay within the gut-brain-endocrine axis. Semaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA), acts as a powerful pharmacological modulator of this complex communication network. Dietary inputs are the chemical messengers that provide the context for these signals.

The food consumed dictates the local gut environment, influences the profile of circulating metabolites, and ultimately determines the body’s systemic response to the potent stimulus of the GLP-1RA. Therefore, dietary strategy is a form of applied systems biology, a method for controlling variables in a complex equation to steer the physiological outcome toward enhanced efficacy and tolerability.

How Does Diet Modulate Semaglutide’s Effect on Energy Homeostasis?

The interaction between semaglutide and diet is deeply rooted in cellular and metabolic physiology. Research, including preclinical models, has demonstrated that the effects of semaglutide are diet-dependent. A study using a mouse model found that semaglutide’s impact on glucose metabolism and growth was significantly different depending on the protein content of the diet.

In protein-malnourished subjects, semaglutide’s effects were altered. Liver transcriptomics from this study suggested that semaglutide might interfere with growth in a malnourished state by altering circadian rhythm and thermogenesis pathways. This highlights a critical concept ∞ the baseline nutritional state of an individual can fundamentally change the body’s response to the medication.

The presence of adequate nutritional substrates, particularly amino acids from protein, appears necessary for the body to correctly interpret and respond to GLP-1RA signaling for healthy metabolic regulation.

This concept extends to the clinical challenge of sarcopenic obesity. The significant weight loss induced by semaglutide, as documented in the STEP clinical trials, is a composite of both adipose tissue and lean body mass. While fat loss is the therapeutic goal, the concurrent loss of muscle tissue presents a clinical risk.

Muscle is a critical site for insulin-mediated glucose uptake. A reduction in muscle mass can, over time, slightly blunt the improvements in insulin sensitivity that are a primary benefit of the therapy. Dietary intervention, specifically ensuring a protein intake sufficient to stimulate muscle protein synthesis (typically recommended at higher levels during periods of caloric deficit), is the primary clinical tool to counteract this effect.

This nutritional strategy provides the necessary substrates to preserve lean mass while the body is in a catabolic state, thereby protecting long-term metabolic health.

Clinical trial data consistently shows that lifestyle interventions, including specific dietary protocols, are integral to achieving the weight loss outcomes seen with semaglutide.

| Trial | Participant Group | Mean Weight Loss (Semaglutide Arm) | Prescribed Lifestyle Intervention Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| STEP 1 | Adults with obesity | -14.9% | 500 kcal/day deficit diet + 150 min/week physical activity. |

| STEP 2 | Adults with type 2 diabetes and obesity | -9.6% | 500 kcal/day deficit diet + 150 min/week physical activity. |

| STEP 4 | Adults with obesity (after 20-week run-in) | -7.9% (from randomization) | 500 kcal/day deficit diet + 150 min/week physical activity. |

Gastrointestinal Mechanisms and Nutritional Science

The most common adverse effects of semaglutide are gastrointestinal in nature, a direct consequence of its mechanism of action. The slowing of gastric emptying, while beneficial for satiety, creates a challenging environment for the digestion of certain macronutrients. The digestion of fat is a complex process requiring emulsification by bile salts and enzymatic breakdown by lipase.

High-fat meals place a significant demand on this system. In the context of delayed gastric emptying, a large bolus of fat can remain in the stomach for an extended period, contributing to symptoms of nausea, bloating, and steatorrhea. This is a matter of physics and biochemistry.

By recommending a diet lower in saturated fats and fried foods, clinicians are applying principles of nutritional science to mitigate a predictable pharmacological effect. The choice of smaller, more frequent meals is a strategy to manage the volume and rate of nutrient entry into the duodenum, preventing the system from becoming overwhelmed. This dietary modulation is a non-pharmacological method of improving the therapeutic index of the medication, allowing patients to tolerate effective doses while minimizing adverse effects.

References

- Blichieri, M. et al. “Semaglutide interferes with postnatal growth in a diet-dependent manner.” 2024.

- Ghusn, W. et al. “The Impact Once-Weekly Semaglutide 2.4 mg Will Have on Clinical Practice ∞ A Focus on the STEP Trials.” Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, vol. 47, no. 10, 2022, pp. 1624-1635.

- Blundell, John, et al. “Effects of oral semaglutide on energy intake, food preference, appetite, control of eating and body weight in subjects with type 2 diabetes.” Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, vol. 23, no. 9, 2021, pp. 2143-2151.

- Haines, Melanie. “Eating More Protein Could Protect You From Common Semaglutide Side Effect.” ENDO 2025, The Endocrine Society, 2025.

- Wilding, John P.H. et al. “Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 384, no. 11, 2021, pp. 989-1002.

- Rubino, Domenica M. et al. “Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults With Overweight or Obesity ∞ The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA, vol. 325, no. 14, 2021, pp. 1414 ∞ 1425.

- Davies, Melanie, et al. “Semaglutide 2·4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2) ∞ a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial.” The Lancet, vol. 397, no. 10278, 2021, pp. 971-984.

Reflection

You have begun to understand the biological mechanisms through which semaglutide operates and the profound influence your nutritional choices have on this process. The information presented here is a map, showing the connections between a molecule, your physiology, and the food on your plate.

This knowledge shifts the dynamic from being a passive recipient of a therapy to an active participant in your own health outcome. The sensations you feel are no longer arbitrary side effects; they are data points, guiding you toward choices that create balance within your system.

Consider the food you eat not as a potential source of conflict with your medication, but as the primary tool for collaboration. How might you structure your meals tomorrow to support your body’s new metabolic reality? What small, consistent adjustment can you make that honors this process of recalibration?

The path to sustained well-being is built upon these informed, deliberate daily choices. This understanding is the foundational step. The next is to apply it, observe the results, and continue to refine the process in a way that is unique to your own body and your personal journey toward vitality.