Fundamentals

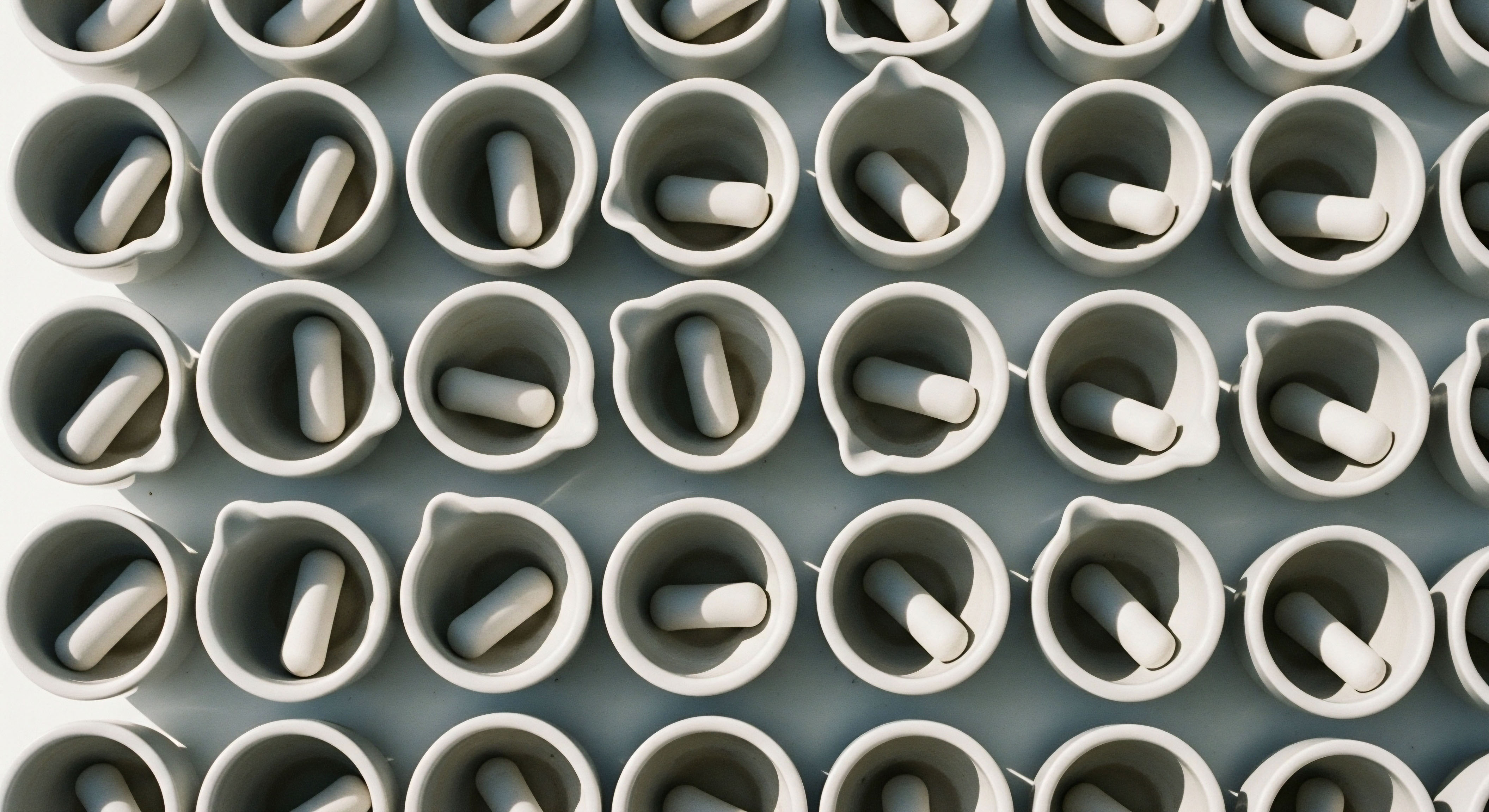

You may have arrived here because a standard medication was not the right fit. Perhaps it contained an excipient you are allergic to, or the required dose for your specific physiology simply is not manufactured. This experience, of needing a medicine tailored specifically to your body’s unique requirements, places you at the heart of one of the most foundational practices in pharmacy ∞ compounding.

It is a process where a pharmacist, in direct response to a physician’s prescription, prepares a medication from its fundamental ingredients for a single individual. This practice stands on the bedrock of the practitioner-patient-pharmacist triad, a collaborative relationship designed to meet a specific therapeutic need that mass-produced pharmaceuticals cannot address.

The entire system of pharmaceutical regulation is built upon a central tension. On one side, there is the immense value of creating bespoke medications that align perfectly with an individual’s biological landscape. On the other, there is the absolute requirement for safety, efficacy, and quality, which is more straightforwardly managed in the highly controlled environment of industrial drug manufacturing.

Every jurisdiction globally must find its own point of equilibrium between these two realities. The rules and legal structures that emerge from this balancing act are what define the international landscape of compounding pharmacy regulations. These frameworks are the blueprints that dictate how, when, and under what conditions a pharmacist can step outside the world of pre-packaged medicines to create a truly personalized therapeutic solution.

A compounding pharmacy creates personalized medications based on a specific prescription, addressing needs that commercially manufactured drugs cannot meet.

The Foundation of Oversight

At its core, the regulation of compounded medicines begins with a fundamental question ∞ is this activity the practice of pharmacy or the manufacturing of drugs? The answer determines which body of rules applies. The practice of pharmacy, including traditional compounding, has historically been overseen at a local level ∞ by state, provincial, or national pharmacy boards.

These organizations set the standards for pharmacists’ training, licensure, and the day-to-day operations of a pharmacy. This localized oversight is rooted in the understanding that compounding serves the needs of an individual patient pursuant to a specific prescription.

Conversely, drug manufacturing is the large-scale production of standardized medicines and is governed by stringent national and international standards, often referred to as Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). These regulations are designed to ensure that every single tablet or vial in a batch of millions is identical and safe.

International bodies like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) work to harmonize these manufacturing standards globally, promoting a shared language of quality and safety. The challenge for regulators worldwide is to draw a clear line, ensuring that pharmacies providing essential, personalized care are not burdened with industrial-level regulations, while also preventing large-scale drug production from occurring under the less stringent oversight intended for traditional compounding.

Intermediate

As we move beyond the foundational concepts, the practical differences in how major global powers regulate compounding become sharply defined. The United States and the European Union offer two distinct models, each shaped by its own history, legal structure, and public health priorities. Understanding these systems reveals the different ways authorities approach the same fundamental goal of providing safe access to customized medications. Their structures provide a clear illustration of the divergence in regulatory philosophy and operational oversight.

The United States Model a System of Tiers

The American regulatory environment for compounding is largely a product of a specific crisis ∞ the 2012 fungal meningitis outbreak traced back to the New England Compounding Center (NECC). This event, which resulted in numerous infections and deaths, exposed critical gaps in oversight and prompted significant legislative action. The resulting Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA) established a two-tiered system that fundamentally reshaped how compounding is regulated.

This system creates two distinct categories of compounding pharmacies:

- 503A Facilities These represent the traditional compounding pharmacy. They are licensed by state boards of pharmacy and are permitted to compound medications only upon receipt of a valid prescription for an individual patient. Their activities are primarily governed by state regulations, although they must also adhere to standards set by the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), specifically chapters like <795> for non-sterile preparations and <797> for sterile ones.

- 503B Facilities This category, known as “outsourcing facilities,” was created by the DQSA. These facilities can compound large batches of sterile drugs, with or without prescriptions, and sell them to healthcare providers. Because they operate more like manufacturers, they are held to a higher standard. They must register voluntarily with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), comply with federal Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) requirements, and are subject to FDA inspections. This dual structure is a direct attempt to apply manufacturing-level controls to large-scale compounders while preserving the traditional, state-regulated model for patient-specific preparations.

The European Union Model a Harmonized Framework

The European Union’s approach is built on a different legal structure. It operates through directives that set binding goals for all member countries, but each nation is responsible for translating those directives into its own national laws. This creates a system that is harmonized in principle yet can vary in its specific application from one country to another.

The foundational EU law, Directive 2001/83/EC, establishes the main rule that all medicinal products require a marketing authorization before they can be sold.

However, the directive provides specific exemptions for compounded products, which are generally understood through two classic definitions:

- Formula Magistralis A medication prepared in a pharmacy according to a medical prescription for an individual patient. This is analogous to the work of a US 503A pharmacy.

- Formula Officinalis A medication prepared in a pharmacy according to the monographs of a pharmacopoeia and intended to be supplied directly to patients served by that pharmacy. This allows for limited batch preparation of commonly used formulations.

A key philosophical principle within the EU framework is that compounding should be complementary to commercially available, authorized medicines. It is intended to fill a therapeutic gap ∞ for instance, when a patient has an allergy to an excipient in a licensed product or requires a liquid form of a drug only sold as a tablet.

The system is designed to discourage “replacement compounding,” where a pharmacy prepares a copy of an authorized drug purely for economic reasons. Furthermore, the EU system introduces the role of the “Qualified Person” (QP), an individual legally responsible for certifying that each batch of a medicinal product meets all quality standards before it is released to the market, a role with no direct equivalent in the US quality unit structure.

How Do US And EU Compounding Regulations Differ In Practice? The US uses a tiered system (503A/503B) with distinct state and federal oversight, while the EU relies on national laws guided by common directives that emphasize compounding as a complement to commercial drugs.

Comparative Regulatory Structures

The table below outlines the primary distinctions between the two regulatory systems, offering a clear comparison of their core components.

| Regulatory Feature | United States | European Union |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Legal Framework | Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA); State Pharmacy Acts | Directive 2001/83/EC; European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.); National Laws |

| Main Regulatory Bodies | FDA (for 503B facilities); State Boards of Pharmacy (for 503A) | National Competent Authorities (e.g. national medicine agencies) |

| Large-Scale Compounding | Permitted for 503B “Outsourcing Facilities” under FDA oversight and cGMP standards. | Generally restricted; emphasis is on individual patient needs. Varies by member state. |

| Key Quality Standards | United States Pharmacopeia (USP <795>, <797>); cGMP for 503B. | European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.); National pharmacopoeias. |

| Product Release Authority | Overseen by the pharmacy’s internal quality control unit. | Requires certification by a designated “Qualified Person” (QP). |

Academic

The operational distinctions in compounding regulations between jurisdictions like the US and EU are surface expressions of deeper, systemic tensions. These tensions revolve around the legal definition of compounding versus manufacturing, the economic pressures that can compromise patient safety, and the ongoing effort to achieve international harmonization in a field intrinsically linked to national healthcare autonomy. Analyzing these pressures reveals the sophisticated challenges that regulators face in a globalized world.

The Jurisdictional Fault Line Compounding versus Manufacturing

The most critical and contentious issue in pharmaceutical compounding regulation is establishing a durable, legally defensible boundary between traditional pharmacy practice and industrial manufacturing. Historically, this was a simpler distinction based on the presence of a patient-specific prescription. The practitioner-patient-pharmacist triad was the defining characteristic of legitimate compounding. However, the rise of large-scale compounding operations that prepare significant quantities of sterile products in anticipation of future prescriptions has blurred this line considerably.

The US approach, with its creation of the 503B outsourcing facility category, is a direct regulatory acknowledgment of this new reality. It essentially carves out a hybrid space ∞ an entity that is not a traditional pharmacy but also not a full-scale manufacturer seeking marketing authorization for a new drug.

These facilities are an attempt to legitimize and control a market reality that was previously operating in a regulatory gray area. In contrast, the European framework, with its doctrinal insistence that compounding remain complementary to authorized medicines, is more resistant to this model. European rules are designed to prevent the very practice that 503B facilities were created to regulate, viewing large-scale compounding without individual prescriptions as an encroachment on the established system of marketing authorizations that protects public health.

Economic Pressures and the Threat of Replacement Compounding

A significant driver of regulatory strain is the economic incentive to use compounded preparations in place of more expensive, commercially available, and authorized medicines. This practice, termed “replacement compounding,” is a primary concern for EU regulators.

The principle of the European Pharmacopoeia is that compounding serves special patient needs, such as an intolerance to an excipient or the need for a non-standard dosage form. Using a compounded version of a drug simply because it is cheaper undermines the entire marketing authorization system, which requires manufacturers to invest heavily in clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy.

If this system can be bypassed for purely economic reasons, the incentive for pharmaceutical innovation and the assurance of quality that comes with it are both eroded.

Why Is The Distinction Between Compounding And Manufacturing So Important? The distinction determines the entire regulatory framework, from the level of oversight and quality standards (GMP) to whether a product can be made in bulk, directly impacting patient safety and the integrity of the drug approval system.

The US system has also grappled with this. While the FDA does not permit compounding of a drug that is essentially a copy of a commercially available product, enforcement can be complex. The debate highlights a philosophical divergence ∞ the US system has created a pathway for large-scale compounding to exist under stricter controls, while the EU system seeks to preserve compounding’s traditional, small-scale role by limiting its economic scope.

International Harmonization Efforts and National Sovereignty

Organizations like the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) and the Council of Europe have made efforts to establish harmonized international standards for pharmacy preparations. The Council of Europe’s Resolution from 2011, for example, aimed to align quality and safety requirements for medicines prepared in pharmacies across Europe, arguing that patient safety should not differ from one member state to another.

These efforts recognize that while compounded products may not enter international commerce in the same way as manufactured drugs, inconsistent quality standards create unequal levels of patient risk.

The table below details key international standards and their functions, illustrating the multi-layered nature of global oversight.

| Organization / Standard | Primary Function | Jurisdictional Application |

|---|---|---|

| US Pharmacopeia (USP) | Sets quality, purity, strength, and identity standards for medicines, food ingredients, and dietary supplements. Chapters <795> and <797> are key for compounding. | Legally recognized in the US; influential worldwide. |

| European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) | Provides common quality standards for medicines and their ingredients for all signatory member states of the European Convention. | Legally binding for 38 European member states, including all EU members. |

| PIC/S GMP Guides | Develops and promotes harmonized Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards and guidance documents for medicinal products. | A non-binding, informal co-operative arrangement between regulatory authorities; highly influential globally. |

| WHO Guidelines | Issues global standards and guidelines on quality assurance for pharmaceuticals, including guidance on compounding for developing countries. | Serve as a model and benchmark for national regulatory authorities worldwide. |

Despite these harmonization efforts, the ultimate authority for regulating pharmacy practice remains at the national level. This reflects a persistent tension between the desire for universal safety standards and the principle of national sovereignty in healthcare. The differences in regulation between the US and EU are therefore not merely technical; they are the outcome of distinct legal traditions, economic realities, and historical events that continue to shape the balance between personalized medicine and collective public health.

References

- Forni, F. et al. “Regulatory framework of pharmaceutical compounding and actual developments of legislation in Europe.” AIR Unimi, 2017.

- Meulenbelt, Maarten. “Replacement Compounding ∞ A Major Threat to the Marketing Authorization System.” Sidley, 2020.

- Pittman, Jill. “Congress Revises Rules for Drug Compounding and Supply-Chain Security.” Pharmaceutical Technology, vol. 37, no. 11, 2013.

- Cohen, Daniel E. and Klint Peebles. “Clinical and Legal Considerations in Pharmaceutical Compounding.” The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, vol. 12, no. 8, 2019, pp. 46-48.

- Howard, R. “The Regulation of Pharmaceutical Compounding and the Determination of Need ∞ A Public Health and First Amendment Analysis.” Harvard Law School, 2006.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Own Therapeutic Path

The journey through the world of compounding regulations reveals that your access to a personalized medication is governed by a complex, global architecture of rules and philosophies. Each framework, whether in North America, Europe, or elsewhere, represents a society’s attempt to balance innovation with safety. Understanding this landscape is the first step.

The next is recognizing that this knowledge empowers you to ask more precise questions ∞ of your physician, of your pharmacist, and of yourself. Your unique physiology and health goals are the true starting point. The regulatory systems are the channels through which a solution must travel, and navigating them successfully begins with a clear understanding of your own biological needs and a partnership with clinicians who can translate those needs into a safe and effective therapeutic reality.