Fundamentals

The feeling of being metabolically adrift, where energy seems to leak away and the body’s internal logic feels scrambled, has a distinct biological signature. Your experience of this subtle, persistent dissonance is a valid and important signal. It speaks a language of cellular communication, a dialect written in glucose, lipids, and inflammatory messengers.

Understanding this language is the first step toward recalibrating your system. Hormones are the primary architects of this internal dialogue. They are the molecules that carry instructions from one part of the body to another, ensuring that the complex machinery of your metabolism operates in a coordinated and efficient manner. When these signals become faint, crossed, or imbalanced, the entire system can lose its rhythm, resulting in the symptoms that disrupt your daily life.

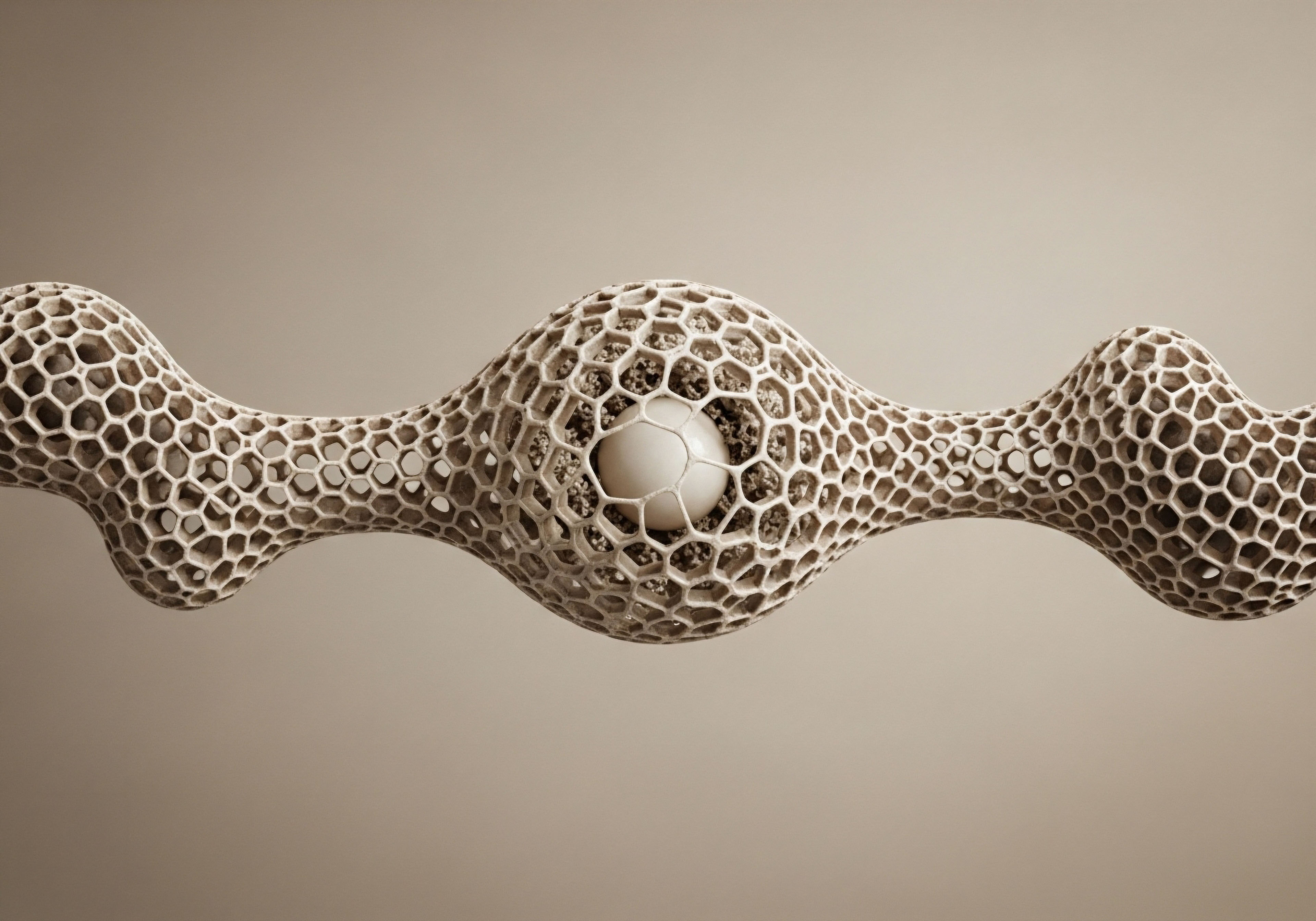

The journey into hormonal wellness begins with appreciating the profound influence of these chemical messengers on your body’s energy economy. Consider your metabolic health as a vast, interconnected power grid. Hormones act as the master controllers, directing where energy is stored, how it is consumed, and the efficiency of its transfer.

Bioidentical hormones, which are molecularly identical to those your body produces, are designed to supplement or restore these critical signals. Their purpose is to re-establish the clear, precise communication your cells require to function optimally. By addressing deficiencies at their source, these protocols aim to restore the foundational stability of your metabolic processes, which can have a cascading effect on everything from body composition to cognitive clarity.

The Core Metabolic Regulators

Three primary hormones form the bedrock of metabolic control, each with a unique and indispensable role. Their balance is a delicate dance, and understanding their individual contributions is essential.

Estradiol the Cellular Sensitizer

Estradiol, the most potent of the three main estrogens, is a powerful modulator of insulin sensitivity. It helps your cells remain responsive to insulin’s signal to take up glucose from the bloodstream. When estradiol levels are optimal, this process is efficient, keeping blood sugar stable and preventing the excess glucose that can be converted into fat.

A decline in estradiol can lead to insulin resistance, a condition where cells become “deaf” to insulin’s message. This forces the pancreas to produce more insulin, creating a cycle that promotes fat storage, particularly in the abdominal region, and increases the risk of metabolic syndrome. Restoring estradiol to a physiologic range can help resensitize cells to insulin, improving glucose management and supporting a healthier body composition.

Progesterone the Calming Counterpart

Progesterone provides a crucial counterbalance to the effects of estrogen and cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. From a metabolic standpoint, it has a calming influence, helping to mitigate the negative effects of chronic stress. Elevated cortisol is known to promote insulin resistance and central fat storage.

Progesterone can help buffer this response. It also possesses a mild diuretic effect, which can help reduce the fluid retention that is sometimes associated with hormonal fluctuations. Its role in promoting restful sleep is also metabolically significant, as poor sleep is a known driver of insulin resistance and weight gain. A healthy progesterone level contributes to a more stable internal environment, protecting metabolic function from the disruptive influence of stress.

Testosterone the Anabolic Architect

Testosterone is a primary driver of lean muscle mass in both men and women. Muscle tissue is highly metabolically active; it is the single largest site of glucose disposal in the body. By promoting the growth and maintenance of muscle, testosterone directly enhances your body’s ability to manage blood sugar.

More muscle means more “parking spots” for glucose, reducing the likelihood of it being stored as fat. Testosterone also directly influences fat metabolism, promoting the breakdown of stored fats for energy. A decline in testosterone contributes to sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass, which in turn slows the metabolic rate and predisposes an individual to fat gain and insulin resistance. Optimizing testosterone levels is a foundational strategy for building and maintaining a robust metabolic engine.

The body’s metabolic function is a direct reflection of its internal hormonal communication.

Understanding Your Metabolic Markers

Your blood work provides a direct window into the effectiveness of your metabolic health. These are not just numbers on a page; they are data points that tell the story of your cellular function. When you begin a bioidentical hormone optimization protocol, tracking these markers over time provides objective feedback on how your body is responding.

The goal is to see these markers shift from patterns indicating stress and inefficiency to patterns reflecting balance and optimal function. This data, combined with your subjective experience of well-being, creates a comprehensive picture of your health journey.

Here are some of the key metabolic markers that are influenced by hormonal balance:

- Fasting Glucose ∞ This measures the amount of sugar in your blood after an overnight fast. It is a primary indicator of how well your body is managing glucose. Hormonal balance, particularly with estradiol and testosterone, helps keep this number in a healthy range.

- Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ∞ This marker provides a three-month average of your blood sugar levels. It gives a longer-term view of glucose control. Improvements in insulin sensitivity driven by hormone optimization will be reflected in a lower HbA1c.

- Lipid Panel (HDL, LDL, Triglycerides) ∞ Hormones have a profound effect on blood lipids. Estradiol tends to raise “good” HDL cholesterol and lower “bad” LDL cholesterol. Testosterone helps lower triglycerides. An imbalanced hormonal state can lead to dyslipidemia, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP) ∞ This is a key marker of systemic inflammation. Hormonal imbalances, particularly low estrogen and testosterone, can contribute to a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation, which is a root cause of many metabolic diseases. Hormone optimization can help lower CRP levels.

By monitoring these markers, you and your clinician can make precise adjustments to your protocol, ensuring that your therapy is tailored to your unique physiology. This data-driven approach moves beyond symptom management and engages with the underlying mechanics of your health, empowering you to make informed decisions about your wellness.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational concepts, a deeper analysis of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy involves understanding the clinical protocols themselves and the specific mechanisms through which they influence metabolic markers. The choice of hormones, their dosages, and, most importantly, their route of administration are all critical variables that determine the ultimate physiological effect.

A well-designed protocol is a highly personalized intervention, crafted to replicate the body’s natural endocrine rhythms and restore the precise signaling that governs metabolic homeostasis. This requires a sophisticated approach that considers the unique needs of both male and female physiology, as well as the pharmacokinetic properties of the therapies being used.

How Do Delivery Systems Alter Metabolic Impact?

The method by which a hormone enters the bloodstream is a determining factor in its metabolic influence. This is because of a physiological process known as first-pass metabolism. When a hormone is taken orally, it is absorbed through the digestive tract and travels directly to the liver before entering systemic circulation.

The liver metabolizes a significant portion of the hormone, altering its structure and producing a cascade of metabolic byproducts. This hepatic first pass can have unintended consequences, particularly for inflammatory and clotting factors. In contrast, transdermal (gels, creams, patches) and injectable routes of administration bypass the liver, delivering the hormone directly into the bloodstream in its unaltered state. This distinction is central to understanding the differing metabolic profiles of various hormone therapy protocols.

Oral estrogens, for example, have been shown to increase the production of C-reactive protein (CRP) and certain clotting factors in the liver. While the estrogen itself is beneficial for insulin sensitivity, this inflammatory and prothrombotic signaling from the liver can offset some of the cardiovascular benefits.

Transdermal estradiol, because it avoids this first-pass effect, does not typically increase CRP and has a more neutral or even favorable effect on clotting factors. This makes the delivery system a key strategic choice in designing a protocol that optimizes metabolic health while minimizing potential risks. The same principle applies to testosterone and progesterone, where the route of administration can significantly alter the balance of benefits.

A Comparison of Delivery Routes

| Delivery Route | Metabolic Pathway | Key Metabolic Implications | Common Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Absorbed via GI tract, undergoes significant first-pass metabolism in the liver. | Can increase inflammatory markers (CRP) and clotting factors. May alter lipid profiles differently than other routes. Oral micronized progesterone has a sedative effect due to its metabolites. | Micronized Progesterone, some older estrogen formulations. |

| Transdermal (Cream/Gel) | Absorbed through the skin directly into systemic circulation, bypassing the liver. | Avoids first-pass effect, leading to a more neutral impact on inflammatory and hemostatic markers. Provides steady, sustained hormone levels. | Estradiol gels, Testosterone creams, compounded multi-hormone creams. |

| Injectable (IM/SubQ) | Injected into muscle or subcutaneous fat, creating a depot for slow release. Bypasses the liver. | Avoids first-pass effect. Allows for less frequent dosing. Can create peaks and troughs in hormone levels depending on the ester and frequency. | Testosterone Cypionate, Testosterone Enanthate. |

| Pellet Implant | Surgically implanted under the skin, providing very long-lasting, steady hormone release. Bypasses the liver. | Avoids first-pass effect. Delivers consistent hormone levels for several months, avoiding compliance issues. Dose cannot be adjusted once implanted. | Testosterone pellets, sometimes Estradiol pellets. |

Clinical Protocols for Male Metabolic Optimization

For men, hormonal optimization typically centers on restoring testosterone to a healthy youthful range. The goal is to reverse the metabolic consequences of andropause, including sarcopenia, insulin resistance, and visceral fat accumulation. A standard, effective protocol involves more than just testosterone; it is a systemic approach designed to manage the downstream effects of hormonal modulation.

A representative protocol often includes:

- Testosterone Cypionate ∞ This is a long-acting ester of testosterone, typically administered via intramuscular or subcutaneous injection. Weekly injections help maintain stable blood levels, avoiding the wide fluctuations that can cause side effects. By restoring testosterone, the protocol directly targets the primary drivers of male metabolic health ∞ lean muscle mass and insulin sensitivity.

- Anastrozole ∞ Testosterone can be converted into estradiol by an enzyme called aromatase. While some estradiol is necessary for male health (including bone density and libido), excess levels can lead to side effects like water retention and gynecomastia. Anastrozole is an aromatase inhibitor that modulates this conversion, keeping estradiol in its optimal range. This is a critical component for metabolic health, as it prevents the potential negative effects of estrogen dominance.

- Gonadorelin or HCG ∞ When the body receives exogenous testosterone, its own natural production via the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis shuts down. Gonadorelin, a GnRH analogue, is used to stimulate the pituitary gland, preserving testicular function and maintaining some endogenous testosterone production. This creates a more balanced and sustainable hormonal environment.

A data-driven protocol adjusts therapy based on the objective feedback of metabolic markers over time.

Clinical Protocols for Female Metabolic Health

For women, particularly those in the perimenopausal and postmenopausal transitions, hormonal therapy is about restoring a complex interplay of several hormones. The aim is to address the metabolic disruption caused by the decline of estradiol, progesterone, and sometimes testosterone.

Protocols for women are highly individualized but often contain these elements:

- Estradiol ∞ This is the primary hormone for addressing menopausal symptoms and their metabolic underpinnings. It is most often prescribed in a transdermal form (gel, patch, or cream) to maximize benefits for insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles while minimizing the risks associated with oral administration.

- Micronized Progesterone ∞ For women with a uterus, progesterone is essential to protect the uterine lining from the growth-promoting effects of estrogen. It is typically taken orally at night, where its metabolite allopregnanolone can promote restful sleep ∞ a significant metabolic benefit. Its calming effects also help buffer the stress hormone cortisol.

- Testosterone ∞ A low dose of testosterone is often a key component of female protocols. Administered transdermally, it helps to build and maintain metabolically active muscle mass, improve energy levels, enhance mood, and restore libido. Its contribution to lean body mass is a direct and powerful way to improve insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic rate.

In both male and female protocols, the long-term management strategy involves regular monitoring of both hormone levels and key metabolic markers. Blood tests for fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, triglycerides, HDL, and hs-CRP provide objective data to guide therapy. Adjustments in dosage or delivery method can then be made to ensure that the protocol is achieving the desired outcome ∞ a restoration of metabolic efficiency and a reduction in the long-term risks associated with hormonal decline.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of the relationship between compounded bioidentical hormones and metabolic markers necessitates a shift in perspective from organ-level effects to the intricate world of cellular and molecular biology. The long-term metabolic influence of any hormonal therapy is ultimately written in the language of gene transcription, enzyme kinetics, and inflammatory signaling cascades.

The most significant variable in this equation, from a biochemical standpoint, is the route of administration. The distinction between oral and transdermal delivery is not merely a matter of convenience; it represents a fundamental divergence in the pharmacodynamic and metabolic pathways that are activated. This section will explore the molecular mechanisms that differentiate these pathways, focusing specifically on how transdermal bioidentical hormone therapy (BHT) modulates hemostatic, inflammatory, and immune factors, thereby shaping long-term metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes.

The Hepatic First Pass Effect a Molecular Perspective

When an oral estrogen preparation is ingested, it is absorbed into the portal venous system, which flows directly to the liver. The hepatocytes of the liver are rich in cytochrome P450 enzymes, which are responsible for xenobiotic metabolism. Oral estradiol is extensively metabolized into estrone and various sulfated and glucuronidated conjugates.

This process has profound consequences. The high concentration of estrogen passing through the liver upregulates the hepatic synthesis of a variety of proteins. These include sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), angiotensinogen, and, critically for metabolic health, a suite of pro-inflammatory and prothrombotic factors.

Specifically, oral estrogen has been demonstrated to increase hepatic production of C-reactive protein (CRP), a sensitive marker of systemic inflammation. It also boosts the synthesis of several key components of the coagulation cascade, including Factor VII, Factor VIII, and fibrinogen, while potentially decreasing levels of antithrombin III, a natural anticoagulant.

This creates a net prothrombotic state. While the estrogen simultaneously improves lipid profiles (lowering LDL, raising HDL), this enhancement of the inflammatory and coagulation systems represents a countervailing risk. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which used oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE), highlighted these risks, showing an increased incidence of venous thromboembolism and stroke. This outcome is a direct consequence of the hepatic first-pass metabolism of oral estrogens.

Transdermal Administration Bypassing the Liver to Alter the Message

Transdermal administration of bioidentical 17β-estradiol fundamentally alters this entire sequence of events. When delivered via a cream, gel, or patch, the hormone is absorbed through the dermis and enters the systemic circulation directly. It reaches the heart, lungs, and peripheral tissues before it ever passes through the liver. This avoidance of the first-pass effect has several critical molecular advantages:

- Physiological Estradiol-to-Estrone Ratio ∞ Transdermal delivery maintains a physiological ratio of estradiol (E2) to estrone (E1), similar to that produced by the premenopausal ovary. Oral administration skews this ratio heavily in favor of estrone, which has a different and weaker binding affinity for estrogen receptors.

- Neutral Effect on Inflammatory Markers ∞ Because the liver is not exposed to a supraphysiological bolus of estrogen, there is no upregulation of hepatic CRP synthesis. Studies consistently show that transdermal estradiol does not increase, and may even decrease, levels of CRP and other inflammatory cytokines like Interleukin-6 (IL-6).

- Favorable Hemostatic Profile ∞ Similarly, transdermal estradiol does not stimulate the hepatic production of prothrombotic factors. Its effect on the coagulation system is largely neutral. This translates to a significantly lower risk of venous thromboembolism compared to oral estrogen, a finding supported by numerous observational studies.

The route of hormonal administration directly dictates the molecular signaling cascades that govern long-term metabolic risk.

Impact on Adipose Tissue and Insulin Signaling

The influence of bioidentical hormones extends deep into the biology of the adipocyte (fat cell) and its role as an endocrine organ. Adipose tissue is not simply a passive storage depot; it actively secretes a range of signaling molecules called adipokines, which regulate insulin sensitivity and inflammation. Testosterone and estradiol play key roles in modulating adipocyte function.

Testosterone, acting through androgen receptors on adipocytes, promotes lipolysis (the breakdown of stored fat) and inhibits lipid uptake. It also appears to direct the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells toward a myogenic (muscle) lineage and away from an adipogenic (fat) lineage. This results in a partitioning of energy substrates away from fat storage and toward lean tissue synthesis.

A decline in testosterone removes this braking effect, contributing to increased adiposity and the secretion of pro-inflammatory adipokines like TNF-alpha and IL-6, which are known to induce insulin resistance.

Estradiol’s role is also complex. It influences the distribution of body fat, favoring a healthier pear-shaped (gynoid) pattern over the more metabolically dangerous apple-shaped (android) pattern of visceral fat accumulation. Visceral adipose tissue is particularly pernicious, secreting high levels of inflammatory cytokines directly into the portal circulation, fueling hepatic insulin resistance.

By maintaining a healthy fat distribution and directly improving insulin signaling within muscle and liver cells, estradiol provides a powerful defense against metabolic decline. Transdermal BHT, by restoring physiological levels of both testosterone and estradiol, can therefore have a profound effect on the entire adipose tissue signaling network, reducing inflammation and improving insulin sensitivity at a systemic level.

Comparative Molecular Impact of Delivery Routes

| Biomarker | Oral Estrogen Administration | Transdermal Estrogen Administration | Molecular Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | Increased | Neutral or Decreased | Oral route causes high hepatic concentration, upregulating CRP gene transcription in hepatocytes. Transdermal route bypasses this. |

| Factor VII & Fibrinogen | Increased | Neutral | Hepatic synthesis of clotting factors is stimulated by the high portal vein concentration of oral estrogen. |

| SHBG | Significantly Increased | Slightly Increased or Neutral | Hepatic synthesis of SHBG is highly sensitive to estrogen exposure. Higher SHBG can reduce free testosterone levels. |

| Triglycerides | Increased | Neutral or Decreased | Oral estrogen can stimulate hepatic triglyceride synthesis. Transdermal testosterone and estradiol tend to lower triglycerides. |

| Insulin Sensitivity | Improved | Improved | Both routes improve insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, but the systemic inflammatory effects of the oral route can be a counteracting force. |

The academic conclusion is that the method of delivery is a primary determinant of the metabolic and cardiovascular safety and efficacy profile of hormone therapy. Compounded transdermal bioidentical hormones, by mimicking the body’s endogenous secretion patterns and avoiding hepatic first-pass metabolism, offer a more targeted and potentially safer approach to restoring hormonal balance.

This model allows for the beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and body composition to be realized without the concomitant increase in inflammatory and prothrombotic signaling associated with oral routes. The long-term influence on metabolic markers is therefore a direct result of this carefully considered biochemical strategy, which prioritizes physiological replication over pharmacological convenience.

References

- Ruiz, A. D. et al. “The effects of compounded bioidentical transdermal hormone therapy on hemostatic, inflammatory, immune factors; cardiovascular biomarkers; quality-of-life measures; and health outcomes in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.” International Journal of Pharmaceutical Compounding, vol. 15, no. 1, 2011, pp. 74-85.

- “The Safety and Effectiveness of Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Therapy.” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The National Academies Press, 2020.

- Holtorf, K. “Bioidentical hormone therapy ∞ a review.” Menopause, vol. 11, no. 3, 2004, pp. 356-67.

- Moskowitz, D. “Bioidentical hormones ∞ An evidence-based review for primary care providers.” Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, vol. 111, no. 3, 2011, pp. 153-64.

- Herrington, D. M. et al. “Effects of estrogen replacement on the progression of coronary-artery atherosclerosis.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 343, no. 8, 2000, pp. 522-9.

- Schierbeck, L. L. et al. “Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women ∞ randomised, placebo-controlled, and open-label extension of the Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study (DOPS).” BMJ, vol. 345, 2012, e6409.

- Colditz, G. A. et al. “The use of estrogens and progestins and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 332, no. 24, 1995, pp. 1589-93.

- Kuhl, H. “Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens ∞ influence of different routes of administration.” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 8, sup1, 2005, pp. 3-63.

Reflection

What Is Your Body’s Metabolic Story?

You have now journeyed through the intricate biological systems that connect your hormonal state to your metabolic vitality. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It provides a framework for understanding the signals your body is sending, translating the subjective feelings of fatigue, brain fog, or weight gain into a coherent conversation about cellular health.

The data points on a lab report and the science of endocrine function are the grammar of this conversation. They provide the objective language to articulate your personal experience.

This information is the beginning of a new chapter in your personal health narrative. The path forward is one of partnership ∞ between you, your body, and a clinician who can help you interpret this complex language. The aim is to move toward a state of function and vitality that feels authentic to you.

The ultimate potential lies not just in alleviating symptoms, but in proactively authoring a future of sustained wellness, built on a deep and respectful understanding of your own unique biology.