Fundamentals

The sensation you feel after an injection, that familiar ache or warmth spreading from the site, is a profound biological story unfolding within your tissues. It is your body’s articulate response to a planned, therapeutic intervention. Understanding this process from a cellular perspective transforms the experience from a passive side effect into an active dialogue between you and your physiology.

This conversation begins the moment the needle pierces the skin and enters the muscle, a tissue rich with blood vessels and nerve endings. The physical pressure of the needle and the introduction of a fluid, whether it is an oil-based hormone preparation like testosterone cypionate or a water-based peptide solution, creates a localized disruption.

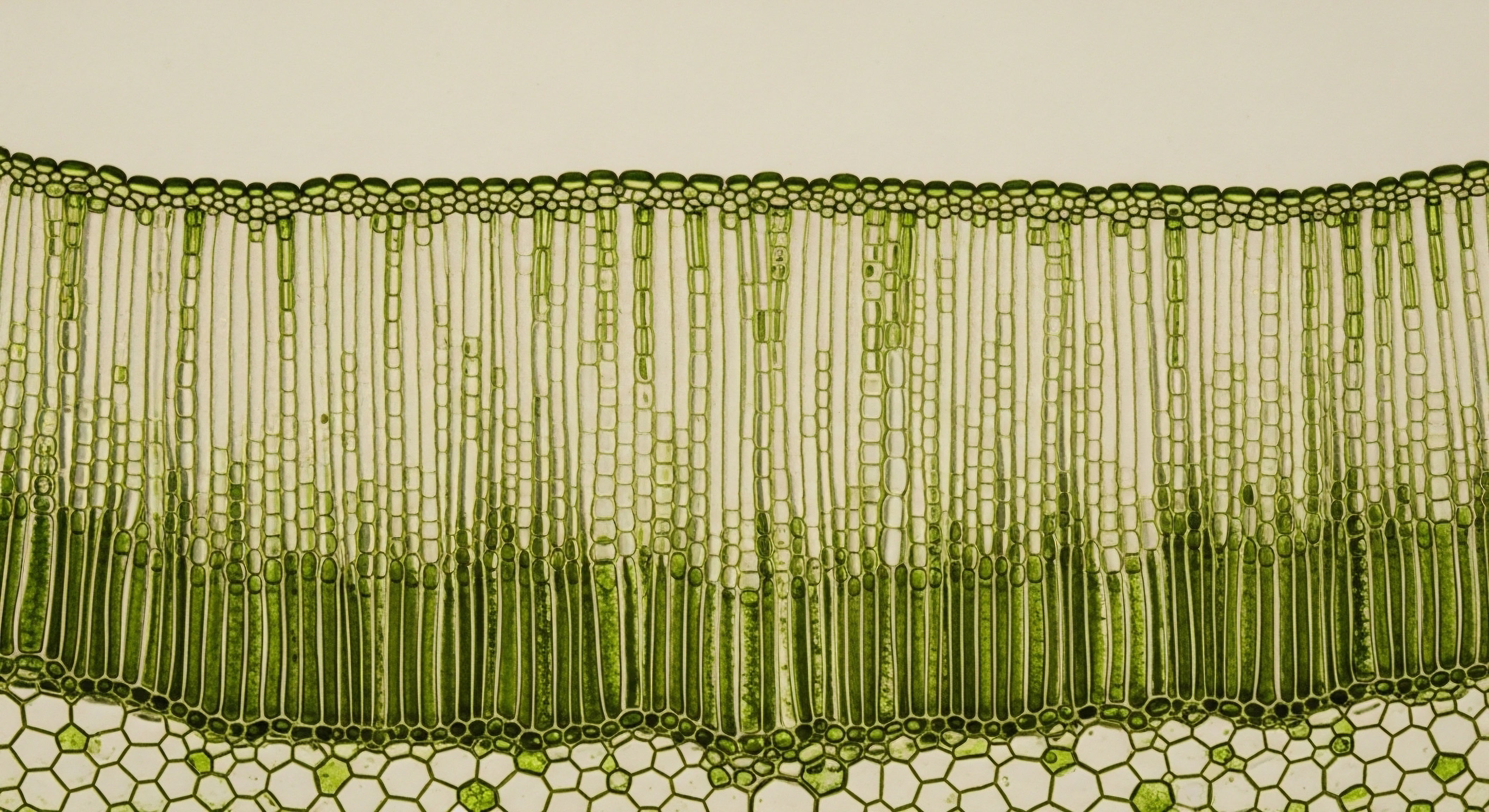

Muscle fibers are gently parted, and microscopic blood vessels may be disturbed. Your body, in its incredible wisdom, perceives this as a localized injury that requires immediate attention.

This perception triggers an immediate and highly organized cellular response. The first cells to arrive at the scene are the neutrophils, a type of white blood cell that acts as the immune system’s frontline infantry. They are summoned by chemical signals released from the disturbed muscle and endothelial cells lining the blood vessels.

Their job is to contain the area and begin the cleanup process. Within hours, a second wave of immune cells, the macrophages, arrives. These are larger, more specialized cells that function as the field commanders and sanitation crew. Macrophages engulf any cellular debris and play a central role in orchestrating the next phase of the healing process.

This initial influx of cells and fluid into the area is what you perceive as swelling and tenderness. It is a sign that your body’s internal surveillance system is functioning exactly as it should, meticulously managing the site of administration.

The initial ache from an injection is the sound of your immune system’s first responders arriving to manage the controlled disruption.

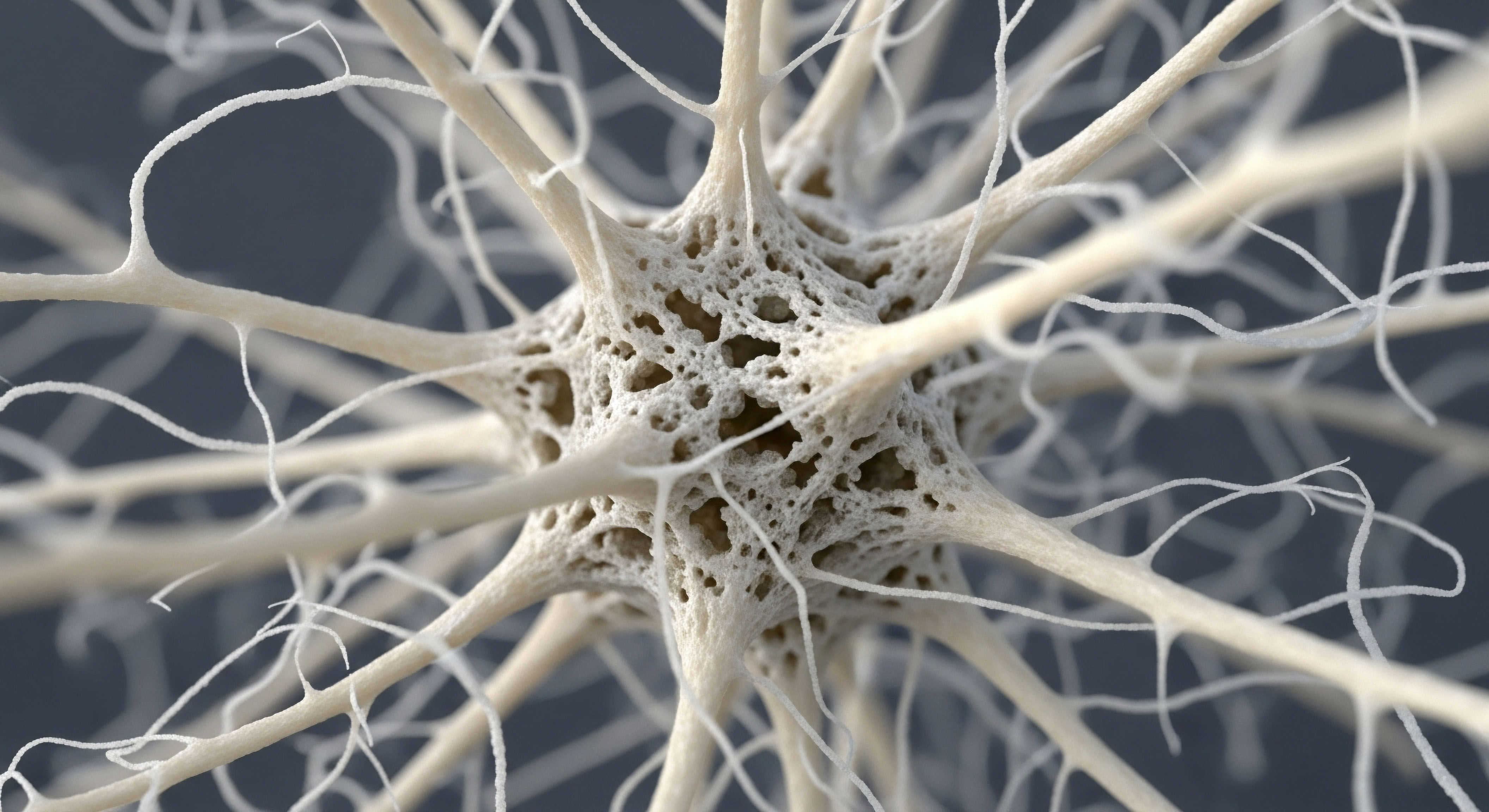

The communication that governs this entire process relies on a sophisticated class of protein messengers called cytokines. When the local cells are disturbed, they release pro-inflammatory cytokines, with names like Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). These molecules are the alarm bells of the immune system.

They travel short distances, binding to receptors on nearby cells, including the specialized nerve endings responsible for sensing pain, called nociceptors. This binding action makes the nerves more sensitive, lowering their threshold for firing. The result is the sensation of pain, a crucial signal that encourages you to protect the area while the body manages the injection.

The same cytokines also cause local blood vessels to dilate, increasing blood flow to bring in more immune cells and resources. This increased circulation is what generates the feeling of warmth at the site. Each of these sensations ∞ pain, swelling, warmth ∞ is a direct, tangible manifestation of this intricate cellular ballet, a confirmation that your body is actively integrating the therapeutic substance you have introduced.

This foundational understanding is deeply relevant to anyone on a personalized wellness protocol, such as hormone optimization or peptide therapy. The substance being injected is a key part of the conversation. The carrier fluid, known as the vehicle, the pH of the solution, and the volume administered all contribute to the intensity and duration of the initial cellular response.

An oil-based vehicle, common for testosterone, is absorbed differently and may create a more prolonged local reaction than a simple saline-based peptide solution. Recognizing this allows you to interpret your body’s feedback with greater clarity. The post-injection experience becomes a source of information, reflecting the dynamic interaction between a specific therapeutic agent and your unique biological terrain. It is the very first step in a cascade that ultimately leads to systemic hormonal balance and enhanced well-being.

Intermediate

Building upon the foundational knowledge of the initial immune response, a deeper clinical perspective reveals how specific characteristics of the injection itself modulate the intensity of post-injection pain. The experience is a direct consequence of the dialogue between the injected substance and the local tissue environment.

This dialogue is governed by a precise set of biochemical and biophysical principles. By understanding these factors, an individual can refine their protocol and injection technique to work in concert with their body’s physiology, minimizing discomfort and optimizing the therapeutic process. The key lies in appreciating the intricate dance between the formulation of the medication and the cellular mechanisms of inflammation.

The Cytokine Orchestra and Nerve Sensitization

The sensation of pain is orchestrated by a specific cast of pro-inflammatory cytokines that do more than just signal for help. Molecules like IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, released by activated macrophages and other immune cells at the injection site, directly interact with the peripheral nerves responsible for pain transmission.

These cytokines bind to receptors on the surface of nociceptors, initiating a cascade of events inside the nerve cell. This process, known as peripheral sensitization, effectively turns up the volume on the pain signal. It lowers the activation threshold of the nerve, meaning that stimuli that might normally go unnoticed, like the simple pressure of clothing, can be perceived as painful.

This is why the injection site can remain tender and sensitive for a day or two following administration. It is a state of heightened local awareness, biochemically induced to protect the area during the initial phase of absorption and tissue repair.

How Do Formulation and Technique Influence the Response?

Every aspect of the injected substance and the method of its delivery has a direct impact on the magnitude of the local inflammatory response. The body is exquisitely sensitive to these variables. For individuals self-administering therapies like testosterone or peptides, mastering these details is a cornerstone of a successful and comfortable long-term protocol.

The Injected Solution a Biochemical Perspective

The composition of the liquid itself is a primary determinant of the cellular reaction. Several key factors are at play:

- Vehicle Composition The carrier fluid for the active medication profoundly influences the local response. Testosterone cypionate, for example, is suspended in a sterile oil (like cottonseed or sesame oil). This oil depot is broken down and absorbed by the body more slowly than a water-based solution. The prolonged presence of this foreign substance can lead to a more sustained, yet typically low-grade, inflammatory presence as macrophages work to process the oil droplets. Peptides, conversely, are often lyophilized (freeze-dried) and reconstituted with bacteriostatic water. This simple aqueous solution is more readily dispersed and absorbed, generally leading to a more transient cellular response.

- Solution pH and Osmolality The body’s internal environment is maintained within a very narrow pH and salt concentration range. An injectable solution that deviates significantly from the body’s natural pH of around 7.4 can act as a chemical irritant, directly stimulating nociceptors and triggering a more robust inflammatory cascade independent of the medication itself. Similarly, a solution with a much higher or lower salt concentration (osmolality) than body fluids can cause localized cellular stress, leading to fluid shifts and increased swelling.

- Volume and Viscosity The physical properties of the fluid matter immensely. Injecting a larger volume of fluid creates more mechanical pressure, stretching the muscle fibers and surrounding connective tissue. This physical distension is itself a signal for inflammation. Likewise, a highly viscous (thick) fluid requires more pressure to inject and disperses more slowly, potentially leading to more significant tissue disruption and a more pronounced sensation of pain. This is a practical consideration when comparing a small-volume subcutaneous peptide injection to a larger-volume intramuscular testosterone injection.

The Injection Process a Biophysical Perspective

The physical act of injection is a clinical skill, and proper technique is paramount for minimizing tissue trauma and the subsequent pain response.

| Technique Factor | Biophysical Impact and Cellular Consequence |

|---|---|

| Needle Gauge and Length |

A larger diameter (lower gauge) needle creates a wider path of tissue disruption, while a needle that is too short for an intramuscular injection may deposit the drug in the subcutaneous fat layer. This can lead to irritation and altered absorption kinetics, as fat tissue is less vascular than muscle. Selecting the appropriate length and a fine gauge (e.g. 25g to 27g) minimizes the initial physical trauma. |

| Injection Speed |

Injecting the fluid too rapidly forces the tissue to expand quickly, causing unnecessary mechanical stress and micro-tearing. A slow, steady injection rate (e.g. 1 mL over 10-20 seconds) allows the muscle fibers to accommodate the fluid more gently, reducing the inflammatory trigger. |

| Injection Site Rotation |

Repeatedly injecting into the exact same spot creates a cycle of chronic localized inflammation and can lead to the formation of fibrous scar tissue. This scar tissue is poorly vascularized, which can impair drug absorption and increase pain. Rotating between different sites (e.g. left and right gluteal muscles, deltoids) allows each area to fully heal and resolve before the next administration. |

| Muscle State |

Injecting into a tense, contracted muscle is more traumatic than injecting into a relaxed one. A contracted muscle resists the needle and the fluid, increasing pain. Ensuring the muscle is relaxed during the injection is a simple yet effective way to reduce the initial trauma. |

By understanding these intermediate concepts, the experience of post-injection pain is reframed. It becomes a readable signal, offering direct feedback on both the product’s formulation and the precision of one’s own technique. This knowledge empowers the individual to move from simply enduring a side effect to actively managing and optimizing their therapeutic protocol for maximum comfort and efficacy.

Academic

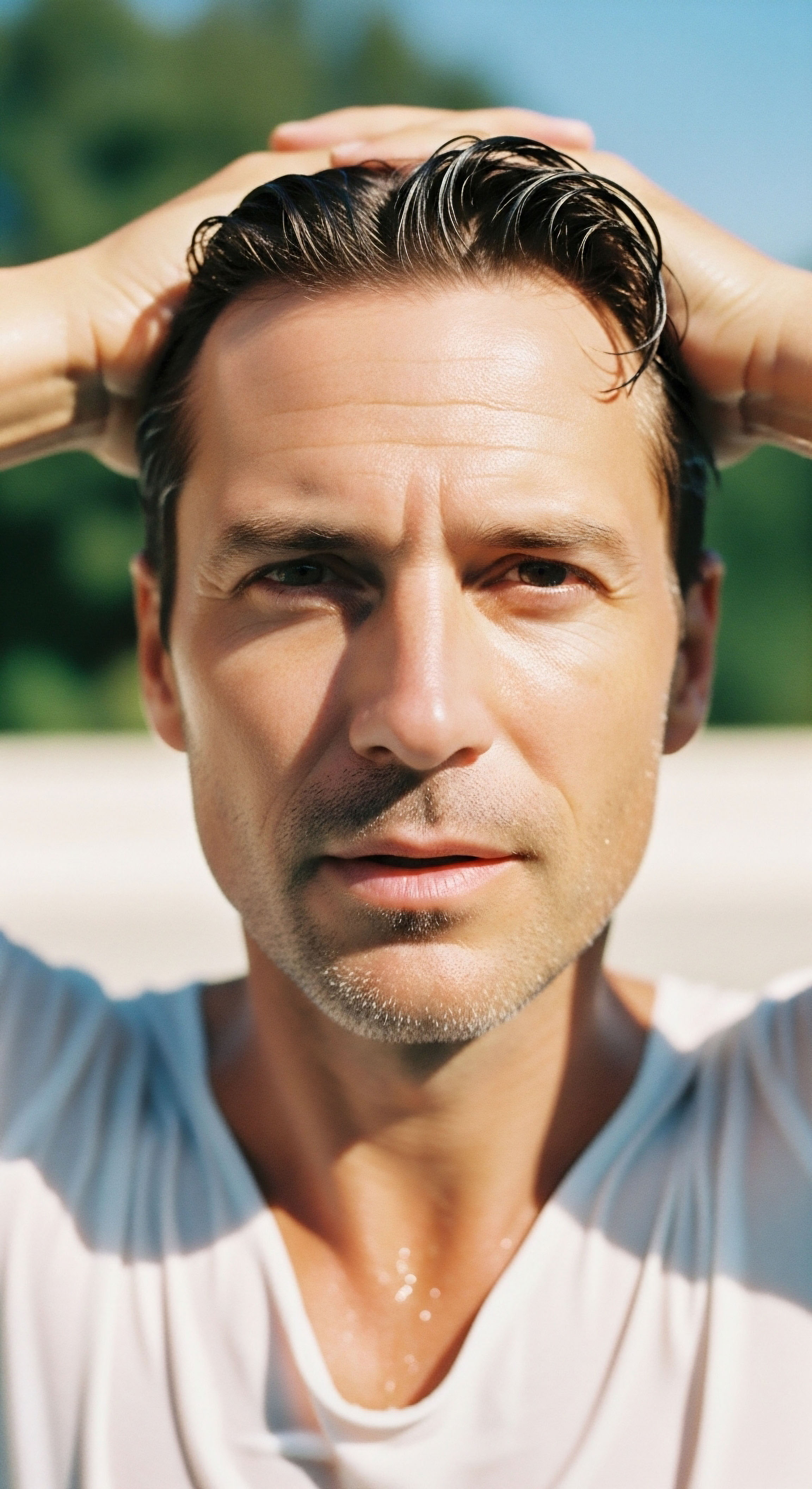

An academic exploration of post-injection pain necessitates a shift in perspective from the localized inflammatory event to a systemic, systems-biology viewpoint. The sensation of pain is the final output of a deeply interconnected network where the immune, nervous, and endocrine systems are in constant, bidirectional communication.

The individual’s baseline hormonal milieu and metabolic health do not merely exist in the background; they actively shape the character, intensity, and duration of the local cellular response to the injection. This integrated understanding is crucial for truly personalized medicine, as it explains why two individuals on identical protocols can have vastly different experiences of post-injection sequelae.

The Neuro-Immune-Endocrine Axis a Unified System

The classical separation of the body’s systems is a conceptual convenience. In reality, they function as a single, integrated metasystem. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis are the central regulators of this network, translating systemic states like stress and hormonal status into biochemical signals that directly modulate immune cell function.

For instance, cortisol, the primary glucocorticoid released via the HPA axis, has potent immunosuppressive effects. Conversely, sex hormones like testosterone and estradiol, governed by the HPG axis, are powerful immunomodulators. Testosterone, for example, generally exerts anti-inflammatory effects, influencing cytokine production by T-cells and macrophages.

This has profound implications for post-injection pain, particularly in the context of hormone replacement therapy. An individual with low testosterone (hypogonadism) may exist in a subtly pro-inflammatory state. Their immune cells may be primed for a more exuberant response to a stimulus.

The first few injections of testosterone cypionate are therefore introduced into an environment that is biochemically predisposed to overreact. The resulting pronounced local inflammation and pain are a direct reflection of the pre-existing systemic condition. As the therapy progresses and systemic testosterone levels normalize, the baseline inflammatory state is recalibrated, and subsequent injections are often met with a much milder local response. The pain, in this context, is a transient marker of a system in the process of correction.

The pain felt at the injection site is a local dialect speaking about the body’s systemic hormonal language.

From Inflammation to Resolution the Role of Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators

The traditional model of inflammation viewed its conclusion as a passive process ∞ the inflammatory signals simply dissipate. Advanced research has overturned this view, revealing that resolution is an active, highly programmed biological process. It is orchestrated by a superfamily of endogenous lipid mediators derived from omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, known as Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators (SPMs). This class includes resolvins, protectins, and maresins.

The inflammatory process initiated by an injection triggers the production of both pro-inflammatory cytokines and, with a slight delay, these pro-resolving mediators. The balance between these two classes of signals determines the fate of the local tissue environment. A successful response is characterized by a rapid, robust inflammatory phase to manage the injection, followed by an equally robust resolution phase to actively shut down the inflammation, clear out the remaining cellular debris, and promote tissue regeneration.

| Process Phase | Key Cellular Players | Primary Mediators | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation (Pro-Inflammatory) |

Neutrophils, Pro-inflammatory Macrophages (M1) |

Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 |

Pathogen/debris clearance, recruitment of immune cells, peripheral nerve sensitization (pain). |

| Resolution (Pro-Resolving) |

Pro-resolving Macrophages (M2), Lymphocytes |

Resolvins (RvD, RvE series), Protectins (PD1), Maresins (MaR1), Lipoxins (LXA4) |

Inhibition of neutrophil influx, stimulation of macrophage-mediated cleanup, counter-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, active analgesia. |

A failure in this resolution pathway is a key mechanism in the transition from acute to chronic pain. If the body cannot efficiently produce or respond to SPMs, the pro-inflammatory signals from the injection can linger, leading to persistent pain, tenderness, and potentially the formation of sterile abscesses or fibrous nodules.

An individual’s capacity to generate SPMs is linked to their systemic health, particularly their nutritional status (availability of precursor fatty acids like EPA and DHA) and their overall metabolic condition. Therefore, chronic or excessive post-injection pain can be a clinical sign of impaired resolution capacity, pointing toward a systemic issue that extends far beyond the injection site itself.

What Is the Impact on Central Nervous System Processing?

The conversation does not stop at the peripheral nerve. Persistent inflammatory signals from a poorly resolved injection site are relayed to the spinal cord and brain. If this signaling is chronic or excessively intense, it can induce a state of central sensitization. In this state, the neurons in the central nervous system become hyperexcitable.

They amplify pain signals, and the brain’s perception of pain becomes disconnected from the actual degree of peripheral stimulus. An individual with central sensitization may experience significant pain from even a perfectly administered injection because their entire neurological system is already on high alert. This phenomenon highlights the ultimate integration of the local event (the injection) into the holistic function of the entire organism, where hormonal status, immune programming, and neurological processing converge to create the subjective experience of pain.

References

- Aalbers, M. et al. “Kinetics of the inflammatory response following intramuscular injection of aluminum adjuvant.” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 170, no. 1, 2013, pp. 1-9.

- Cui, Jian-Guo, et al. “Cytokines, Inflammation and Pain.” International Anesthesiology Clinics, vol. 45, no. 2, 2007, pp. 27-37.

- Usach, I. et al. “Understanding and Minimising Injection-Site Pain Following Subcutaneous Administration of Biologics ∞ A Narrative Review.” Drug Delivery and Translational Research, vol. 11, no. 2, 2021, pp. 389-401.

- Ji, Ru-Rong, et al. “Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators as Resolution Pharmacology for the Control of Pain and Itch.” Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, vol. 63, 2023, pp. 273-293.

- Besedovsky, H. O. and A. del Rey. “Neuroendocrine-Immunological Interactions in Health and Disease.” Frontiers in Bioscience, vol. E3, 2011, pp. 132-140.

- Tracey, Kevin J. “The inflammatory reflex.” Nature, vol. 420, no. 6917, 2002, pp. 853-859.

- Serhan, Charles N. “Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology.” Nature, vol. 510, no. 7503, 2014, pp. 92-101.

- Ziemssen, Tjalf, and Martin S. Kern. “Psychoneuroimmunology ∞ Cross-talk between the immune and nervous systems.” Journal of Neurology, vol. 254, no. S2, 2007, pp. II8-II11.

- Ogawa, Sumiyo, et al. “Intramuscular injection technique ∞ an integrative review.” International Journal of Nursing Studies, vol. 41, no. 2, 2004, pp. 129-140.

- Scholz, Joachim, and Clifford J. Woolf. “The neuropathic pain triad ∞ neurons, immune cells and glia.” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 10, no. 11, 2007, pp. 1361-1368.

Reflection

The knowledge that post-injection pain is a detailed biological narrative offers a new lens through which to view your health journey. Each sensation is a data point, a message from your body’s intricate internal network. What is this feedback telling you about your unique physiology?

Does your body’s response feel sharp and brief, suggesting an efficient and well-regulated system? Or does it linger, perhaps hinting at an underlying inflammatory tone or a need to refine your protocol? This awareness shifts the dynamic from one of passive reception to active partnership.

The goal is a therapeutic process that feels seamless, a quiet integration of external support into your body’s own powerful systems of balance and healing. Consider this new understanding not as a final answer, but as the beginning of a more profound and informed conversation with your own biology, a path toward reclaiming vitality with precision and self-awareness.