Fundamentals

You may recognize the feeling. A persistent state of being ‘on,’ a mind that races when it should be resting, coupled with a deep-seated physical exhaustion that sleep fails to resolve. This experience, often described as feeling ‘wired and tired,’ is a tangible, physiological state.

It originates within the intricate communication network of your endocrine system, specifically from the interplay between your adrenal glands and your body’s hormonal signals for growth and repair. Your body is designed for resilience, equipped with sophisticated systems to manage challenges. Understanding the language of these systems is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

At the center of your body’s response to any demand, whether physical, mental, or emotional, lies the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Think of this as your internal command center for managing stress. When your brain perceives a challenge, the hypothalamus sends a signal to the pituitary gland, which in turn signals the adrenal glands, situated atop your kidneys, to release cortisol.

Cortisol is your primary stress hormone, a powerful metabolic tool designed to mobilize energy for immediate use. It sharpens focus, increases blood sugar for fuel, and modulates inflammation, all essential actions for short-term survival.

The Role of Cortisol in a Stress Response

Cortisol’s function is fundamentally about resource allocation. In a moment of acute stress, it ensures your survival by prioritizing immediate needs. Energy is diverted to your muscles and brain. Systems that are non-essential for immediate flight or confrontation, such as digestion, immune surveillance, and long-term tissue repair, are temporarily suppressed.

This is an elegant and effective survival mechanism honed over millennia. The system is designed to activate, resolve the stressor, and then return to a state of balance, or homeostasis. The challenge in modern life arises when the ‘off’ switch is rarely flipped.

The sensation of being simultaneously exhausted and on high alert is a direct reflection of how the body’s stress and repair systems interact.

Growth Hormone the Architect of Renewal

Working in a delicate counterbalance to the catabolic (breakdown) nature of cortisol is Growth Hormone (GH). Produced by the pituitary gland, primarily during deep sleep, GH is the master hormone of repair, regeneration, and growth. Its role is profoundly anabolic, meaning it builds tissues up.

GH stimulates cellular repair, promotes muscle growth, supports bone density, and aids in the metabolism of fat for energy. It is the architect of your body’s nightly restoration project, rebuilding what the day’s activities have worn down. The peak release of GH occurs in the first few hours of deep, restorative sleep, a time when the body is in a state of profound rest and recovery.

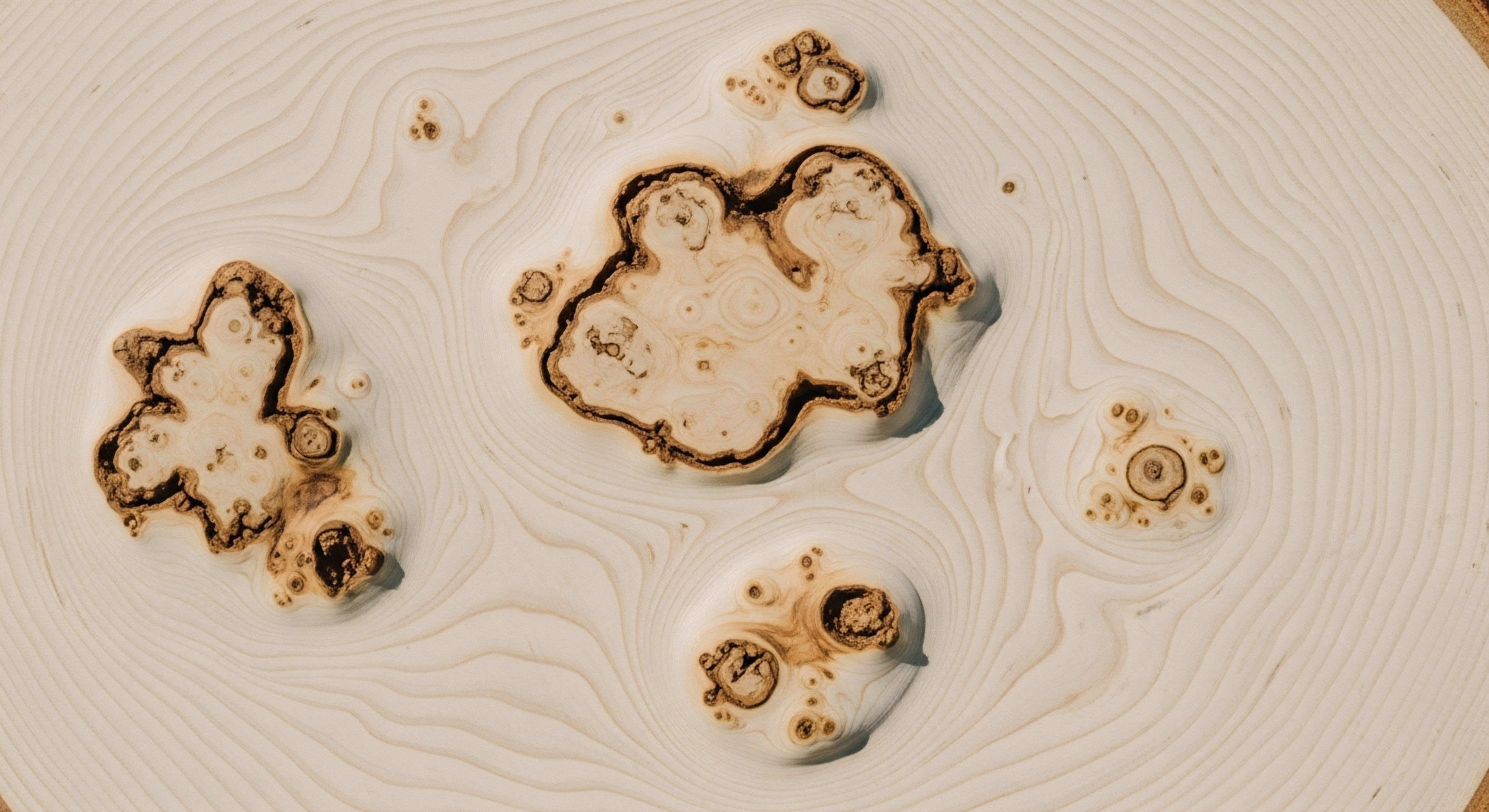

The relationship between cortisol and GH is one of physiological opposition. Cortisol is the hormone of daytime action and energy mobilization. GH is the hormone of nighttime repair and energy storage. Their secretion is meant to follow a natural circadian rhythm, with cortisol peaking in the morning to promote wakefulness and gradually declining throughout the day, reaching its lowest point at night.

This dip in cortisol is the permissive signal for the robust release of GH. This rhythmic dance is foundational to your health, governing your energy levels, your resilience, and your capacity for recovery.

Intermediate

The elegant, rhythmic opposition between cortisol and Growth Hormone is central to metabolic health. When the HPA axis is functioning optimally, this hormonal relationship supports daily energy and nightly repair. Chronic stress introduces a significant disruption to this system.

A persistent state of high alert, driven by work pressures, emotional challenges, or poor sleep hygiene, leads to a dysregulation of the HPA axis. This transforms the acute, helpful release of cortisol into a chronic, elevated pattern that directly interferes with GH secretion and function.

How Does Stress Alter Cortisol Rhythms

A healthy cortisol rhythm is characterized by a significant peak within 30-60 minutes of waking, known as the Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR), followed by a steady decline throughout the day. Chronic stress flattens this curve. Cortisol levels may be sluggish in the morning, contributing to feelings of grogginess and an inability to feel awake.

Concurrently, levels may fail to decrease in the evening, remaining elevated when they should be at their lowest. This elevated nighttime cortisol is particularly damaging to the GH axis. The pituitary gland is exquisitely sensitive to circulating cortisol. High levels of cortisol at night send a powerful inhibitory signal to the pituitary, effectively blunting the primary, deep-sleep-associated pulse of GH.

Chronic stress reshapes the body’s natural 24-hour cortisol cycle, directly suppressing the nighttime release of Growth Hormone.

This suppression occurs through several mechanisms. Elevated cortisol enhances the brain’s release of somatostatin, a hormone whose primary function is to inhibit the release of other hormones, including GH. At the same time, high cortisol levels can decrease the pituitary’s sensitivity to Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH), the signal from the hypothalamus that should trigger GH production.

The result is a dual blockade ∞ the ‘go’ signal for GH is weakened, and the ‘stop’ signal is amplified. Your body’s capacity for overnight repair is compromised, night after night.

Comparing Adrenal and Growth Hormone Responses

The impact of stress on your hormonal systems can be understood by comparing the body’s acute and chronic response patterns. The initial reaction is adaptive, while the long-term state becomes maladaptive and damaging.

| System Response | Acute Stress (Adaptive) | Chronic Stress (Maladaptive) |

|---|---|---|

| HPA Axis Activity | Rapid, robust activation with a swift return to baseline. | Sustained activation, leading to elevated or dysrhythmic cortisol levels. |

| Cortisol Pattern | Sharp, temporary increase to mobilize energy. | Chronically high levels, or a flattened curve with elevated nighttime cortisol. |

| GH Secretion | Minor, transient suppression. | Significant, sustained suppression, especially the main nocturnal pulse. |

| Metabolic Effect | Temporary increase in blood glucose for immediate energy. | Contributes to insulin resistance, fat storage, and muscle protein breakdown. |

| Subjective Feeling | Alert, focused, energized. | ‘Wired and tired,’ fatigued, poor sleep, difficulty recovering. |

Supporting the Growth Hormone Axis

Understanding this dynamic opens the door to targeted interventions. While managing the source of stress is the foundational strategy, specific protocols can help support the GH axis directly. Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy utilizes peptides like Sermorelin, CJC-1295, and Ipamorelin. These are not GH itself, but secretagogues, molecules that signal the pituitary gland to produce and release its own GH.

By stimulating the pituitary in a manner that mimics the body’s natural pulsatile release, these therapies can help restore a more youthful and robust GH output, even in the face of some HPA axis dysregulation. For instance, Ipamorelin provides a strong, clean pulse of GH release with minimal impact on cortisol, making it a sophisticated tool for recalibrating this delicate hormonal balance.

Academic

The antagonistic relationship between glucocorticoids and the somatotropic axis is a complex interplay of central and peripheral mechanisms. While chronic hypercortisolism is unequivocally associated with the suppression of Growth Hormone (GH) secretion, the precise molecular actions are multifaceted.

The effects are dose-dependent and duration-dependent, exhibiting a biphasic nature where both excessive and deficient cortisol levels can impair the functional reserve of GH-producing somatotroph cells in the anterior pituitary. A deep examination of these pathways reveals a sophisticated regulatory network that is highly vulnerable to disruption by chronic stress.

Central Inhibition at the Hypothalamic-Pituitary Level

Elevated glucocorticoids exert powerful centrally-mediated inhibitory effects on the GH axis. One primary mechanism is the potentiation of somatostatin (SST) release from the periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. SST acts on pituitary somatotrophs via its specific receptors (SSTRs), primarily SSTR2 and SSTR5, to inhibit GH synthesis and secretion.

Cortisol increases both SST synthesis and the sensitivity of hypothalamic neurons to signals that trigger SST release. This creates a powerful inhibitory tone that directly opposes the stimulatory input of Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH).

Simultaneously, glucocorticoids can directly attenuate the action of GHRH at the pituitary level. Research suggests this is not due to a simple downregulation of GHRH receptors but rather a post-receptor mechanism. High cortisol levels interfere with the intracellular signaling cascade that follows GHRH binding.

Specifically, they can impair the generation of cyclic AMP (cAMP), a critical second messenger in the GHRH signaling pathway. This interference happens at a point distal to the G protein-adenylyl cyclase complex, suggesting an effect on the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway or downstream phosphorylation events that are necessary for GH gene transcription and vesicle exocytosis.

Glucocorticoid excess systematically dismantles the Growth Hormone axis by amplifying inhibitory signals and disrupting the intracellular machinery for its production.

Molecular Mechanisms of Somatotroph Suppression

The direct action of cortisol on the pituitary somatotroph is a key area of investigation. Glucocorticoids can modulate ion channel activity, which is critical for the secretory process. Studies have shown that cortisol can inhibit voltage-gated calcium channels.

The influx of calcium into the cell is a final, critical trigger for the fusion of GH-containing secretory granules with the cell membrane and their subsequent release. By dampening this calcium signal, cortisol effectively applies a brake on the exocytotic process, even when stimulatory signals are present.

- Somatostatin Potentiation ∞ Cortisol upregulates the expression and release of hypothalamic somatostatin, the primary inhibitor of GH secretion.

- GHRH Signal Attenuation ∞ The intracellular signaling cascade following GHRH receptor activation is blunted, particularly affecting the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway.

- Calcium Channel Modulation ∞ Cortisol can directly inhibit voltage-dependent calcium channels on somatotrophs, reducing the calcium influx required for GH exocytosis.

- Peripheral GH Resistance ∞ Cortisol induces a state of resistance to GH’s effects in target tissues like the liver, impairing the production of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1).

Peripheral Resistance and the GH-IGF-1 Axis

The impact of hypercortisolism extends beyond central suppression of GH secretion. It also induces a state of peripheral GH resistance, primarily at the liver, which is the main site of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) production. IGF-1 mediates many of the anabolic and growth-promoting effects of GH.

Cortisol interferes with the ability of GH to stimulate IGF-1 synthesis and release from hepatocytes. This contributes to a clinical picture of low IGF-1 levels despite potentially normal or even elevated GH pulses in some compensatory states. The result is a functional GH deficiency, where the body’s tissues cannot properly respond to the GH that is present. This uncoupling of the GH-IGF-1 axis is a hallmark of chronic catabolic states, including prolonged stress.

| Molecular Target | Effect of Excess Cortisol | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamic SST Neurons | Increased synthesis and release of somatostatin. | Enhanced inhibition of pituitary GH release. |

| Pituitary Somatotrophs | Impaired cAMP/PKA signaling; inhibited Ca2+ influx. | Reduced GH synthesis and secretion. |

| Hepatic Cells (Liver) | Inhibition of GH receptor signaling (JAK-STAT pathway). | Decreased IGF-1 production; peripheral GH resistance. |

| Adipose Tissue | Stimulation of lipolysis. | Increased free fatty acids, which can also suppress GH release. |

References

- Krieger, D. T. “Glucocorticoids and the regulation of growth hormone secretion.” Medical Clinics of North America, vol. 69, no. 5, 1985, pp. 805-28.

- Giustina, A. and G. Mazziotti. “Glucocorticoids and the regulation of growth hormone secretion.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 13, no. 7, 2002, pp. 296-300.

- Sartorio, A. et al. “The effect of glucocorticoids on the gas-releasing hormone/insulin-like growth factor-I axis.” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 26, no. 7 Suppl, 2003, pp. 48-52.

- Dieguez, C. et al. “The role of glucocorticoids in the neuroregulation of growth hormone secretion.” Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 12, no. 3, 1999, pp. 255-60.

- Takahashi, Y. et al. “Acute effects of corticosteroids on growth hormone, TSH and prolactin secretion in normal men.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 43, no. 5, 1976, pp. 1104-11.

- Wehrenberg, W. B. et al. “The effect of adrenalectomy and glucocorticoid replacement on growth hormone secretion in the rat.” Endocrinology, vol. 112, no. 6, 1983, pp. 2046-51.

- Valentino, R. J. and A. E. Kalyvas. “Neurobiological mechanisms of stress-related psychiatric disorders.” Current Opinion in Pharmacology, vol. 12, no. 5, 2012, pp. 637-43.

- Lonsdale, D. “A review of the biochemistry, metabolism and clinical benefits of thiamin(e) and its derivatives.” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 3, no. 1, 2006, pp. 49-59.

- Dieguez, C. and C. V. Mobbs. “Glucocorticoids and the neuroregulation of growth hormone secretion.” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 92, no. 6, 1993, pp. 2575-9.

- Fraser, R. et al. “Cortisol ∞ clinical and therapeutic aspects.” The Lancet, vol. 2, no. 7996, 1976, pp. 1119-21.

Reflection

What Is Your Body’s Rhythm Telling You

The information presented here provides a biological blueprint for how your internal world responds to your external one. The science connects the subjective feeling of being ‘wired and tired’ to a concrete, measurable hormonal cascade. Consider your own daily patterns. When do you feel most energetic? When does fatigue set in?

How restorative is your sleep? Your body communicates its state of balance or imbalance through these signals. Viewing these feelings through the lens of the HPA axis and the GH system transforms them from passive symptoms into active data points. This knowledge is the foundational tool for beginning a more intentional conversation with your own physiology, a conversation aimed at restoring the profound, rhythmic collaboration between stress and renewal.

Glossary

pituitary gland

cortisol

growth hormone

circadian rhythm

chronic stress

hpa axis

cortisol levels

somatostatin

ghrh

peptide therapy

ipamorelin

glucocorticoids