Fundamentals

You hold the results of a wellness test in your hands, or perhaps you are contemplating the purchase. The allure is undeniable a glimpse into the very code that dictates your body’s unique responses to food, exercise, and the passage of time.

You feel a pull towards understanding the deepest parts of your own biology, a desire to reclaim a sense of control over your health narrative. This feeling is valid and important. It is the beginning of a profound journey into personal science.

The information contained within your genes is the foundational blueprint of your metabolic and endocrine function. It offers clues to your body’s predispositions, its strengths, and the areas that may require focused support. This is the architectural schematic of your vitality.

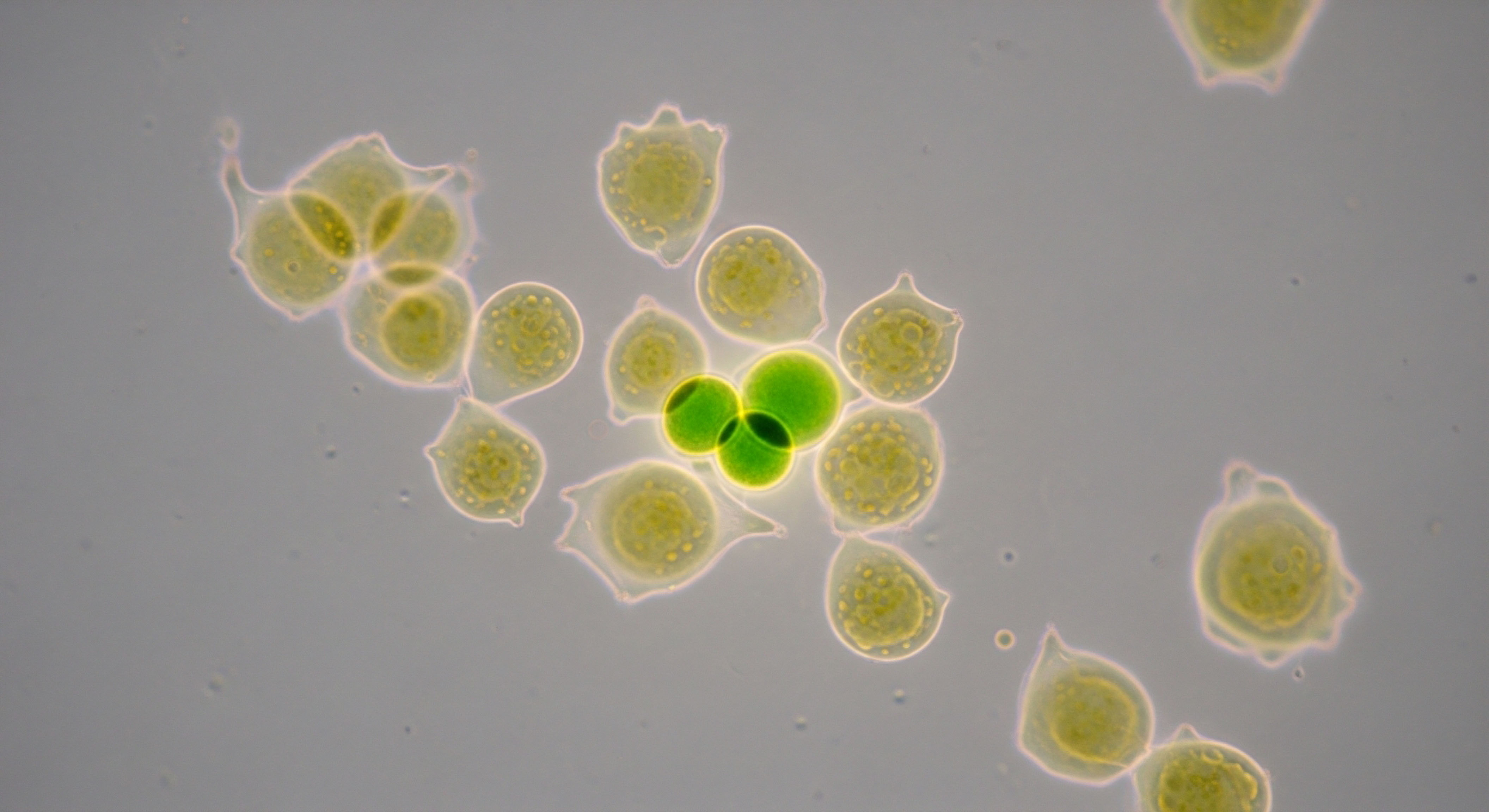

When you submit a saliva sample, you are providing access to this intimate schematic. The data extracted is a vast sequence of genetic markers, primarily single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which are variations at single positions in a DNA sequence. These variations are what make you unique.

They can influence everything from your likelihood of having a particular hair color to how efficiently your body processes certain nutrients or metabolizes hormones. Companies that offer these tests are commercial entities. They provide a service, and in return, they receive your genetic data. Understanding this transaction is the first step in protecting your biological information.

Your genetic data is the operational manual for your body’s most intricate systems, and its protection is integral to your long-term health autonomy.

What Is Genetic Data in This Context?

The information derived from a wellness test is a digital representation of your unique genetic makeup. This is composed of your genotype, the specific set of genes you possess. While the full human genome is massive, consumer tests typically analyze a curated set of SNPs known to be associated with particular traits or health risks.

The results you receive are an interpretation of what these specific markers might mean for you. This data can be stored, copied, and analyzed indefinitely. Its permanence is one of its most defining characteristics. Unlike a password, you cannot change your genetic code if it is compromised.

The Regulatory Landscape a Protective Framework with Gaps

Navigating the world of genetic data requires an awareness of the legal structures in place to protect you. Two key pieces of federal legislation in the United States govern the use of genetic information, though their application has significant limitations in the consumer wellness space.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is a law that protects the privacy of your medical information. It establishes a federal standard for the security of protected health information (PHI) as handled by covered entities, which include healthcare providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses.

Most direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing companies are not considered covered entities under HIPAA. This means the genetic data you provide to them does not have the same legal protections as the records held by your doctor.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) offers a different layer of security. GINA prohibits health insurers from using your genetic information to make decisions about your eligibility or premiums. It also prevents employers from using your genetic data in hiring, firing, or promotion decisions. These are valuable protections.

GINA’s scope is specifically defined. It does not extend to other forms of insurance like life, disability, or long-term care insurance. These entities may still be able to request or use your genetic information to assess risk, which has direct implications for your financial and future planning.

Intermediate

Understanding the fundamental nature of your genetic data and the existing regulatory environment is the first critical step. The next involves taking proactive measures to build a fortress around your biological blueprint. This requires a conscious and deliberate approach to how you interact with genetic testing services, from the moment you consider a purchase to long after you have received your results.

Protecting your data is an active process of managing consent, controlling your digital footprint, and understanding the true meaning of “anonymity” in the digital age.

Your genetic information has implications that extend beyond your own health. It reveals information about your biological relatives, who share portions of your DNA. The decision to test, therefore, has a familial dimension. A responsible approach acknowledges that your data is part of a larger, interconnected family story. The strategies you employ to protect your information contribute to the security of your relatives as well.

Before You Test a Pre-Emptive Strategy

The most powerful time to protect your data is before you have even shared it. This is when you have the greatest leverage and control. A thorough evaluation of the company and its policies is essential.

- Scrutinize the Privacy Policy ∞ This document is a contract that details how your data will be used, shared, and stored. Look for clear language about third-party sharing. Does the company share data with research partners, pharmaceutical companies, or other commercial entities? What level of consent is required for this sharing? Avoid companies with vague or overly broad policies.

- Understand the Consent Agreement ∞ Often, you will be presented with separate consent options. One is for the core service of providing your results. Another, typically optional, is for your data to be used in research. Understand that consenting to research may mean your “de-identified” data is shared with a wide array of academic and commercial partners. You have the right to decline this secondary consent.

- Create a Digital Shield ∞ Consider using a pseudonym for your account. Use a unique, secure email address created specifically for this purpose. This creates a buffer between your public identity and your genetic profile. Avoid linking your social media accounts or other personal identifiers to the testing service.

What Are the Risks of Unprotected Genetic Data?

The risks associated with compromised genetic data are multifaceted. They range from the commercial to the deeply personal. A data breach at a testing company could expose your raw genetic data along with personal identifiers. This information could be sold or used for targeted advertising.

More subtly, your data, even when “anonymized,” can be used by data brokers to build a detailed profile of you, which can then be sold to other companies, including insurers not covered by GINA. This could lead to higher premiums for life or disability insurance based on a statistical risk you may or may not ever develop.

True data protection moves beyond reliance on company policies and involves creating personal firewalls to insulate your identity from your biological information.

The Illusion of Anonymity Re-Identification Risk

Many companies state that they only share “de-identified” or “anonymized” data for research. This means they remove direct identifiers like your name and address. This practice is insufficient to guarantee privacy. Researchers have repeatedly demonstrated that it is possible to re-identify individuals from anonymized genetic datasets by cross-referencing them with other publicly available information, such as genealogical databases, voter registration lists, or social media profiles.

Think of it like this ∞ your genome contains a unique combination of rare variants. These rare variants act like a fingerprint. If a small portion of your genetic data is available in one database (the “anonymized” research data) and another small portion is available in another database that has your name attached (perhaps a public genealogy site a distant cousin uses), algorithms can match the overlapping “fingerprints” and link your name to the supposedly anonymous research data. This process of re-identification is a genuine threat to individual privacy.

| Feature | Description | What to Look For |

|---|---|---|

| Data Deletion | The ability to request the complete deletion of your genetic data and destruction of your biological sample. | A clear, accessible process for data and sample deletion, with a specified timeframe for completion. |

| Granular Consent | Separate, specific consent options for different uses of your data (e.g. core service vs. third-party research). | An “opt-in” model for research, where you must actively agree, rather than an “opt-out” model. |

| Third-Party Sharing Policy | The company’s rules regarding sharing your data with partners, law enforcement, and other entities. | Explicit statements about when and why data is shared, and a commitment to require a warrant for law enforcement requests. |

| Security Practices | The technical measures, like encryption, used to protect data from breaches. | Commitment to strong encryption for data both in transit and at rest, and regular security audits. |

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of genetic data protection requires moving beyond user-end strategies and into a systemic analysis of the data economy, the technical mechanisms of privacy erosion, and the ethical architecture of consent. The value of genetic data is not merely in the service provided to the consumer; it is a highly prized commodity in a multi-billion dollar data brokerage market.

Your genetic blueprint, when aggregated with millions of others, becomes a powerful tool for pharmaceutical development, predictive modeling, and targeted marketing. Protecting your data, therefore, is an act of asserting sovereignty over your most fundamental biological asset in the face of this powerful economic engine.

The Economic Underpinnings of Genetic Data

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies often have business models that depend on the secondary use of customer data. While the sale of a testing kit generates initial revenue, the long-term value lies in the massive, proprietary databases of genetic and self-reported health information they accumulate.

Pharmaceutical companies are willing to pay substantial sums for access to this data to accelerate drug discovery and identify patient populations for clinical trials. This creates a powerful incentive for testing companies to encourage users to consent to research. The consent agreement you sign is a legal instrument that facilitates this transfer of value. The language within these agreements is meticulously crafted to provide broad permissions for data use, often in perpetuity.

How Can My Anonymized Data Be Re-Identified?

The concept of “anonymization” as applied to genetic data is a misnomer from a technical standpoint. A more accurate term is “pseudonymization,” where direct identifiers are replaced with a code. As research has conclusively shown, this is a fragile barrier. The study by Gymrek et al. (2013) was a landmark demonstration of this vulnerability.

Researchers were able to re-identify multiple participants in the 1000 Genomes Project by cross-referencing short tandem repeat (STR) markers on the Y chromosome with publicly accessible genealogical databases that contained surnames. This technique, known as surname inference, shows that even a small amount of genetic data can be used to breach anonymity.

More recent techniques have expanded these capabilities. Identity inference using long-range familial searches can identify an individual even through distant relatives. A 2018 study in Science estimated that a genetic database needs to cover only 2% of a target population to provide a third-cousin match to nearly any person, which is often enough to triangulate an identity.

As consumer databases grow, the probability of any given person being identifiable through a relative approaches certainty. This reality fundamentally challenges the traditional model of research consent, which is predicated on the promise of anonymity.

In the digital ecosystem, genetic data is not truly anonymous; it is merely awaiting the right algorithm and a corresponding dataset to be re-associated with its owner.

| Vulnerability Type | Mechanism | Primary Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Breach | Unauthorized access to a company’s servers via hacking (e.g. credential stuffing, phishing). | Exposure of raw genetic data and linked personal information (name, address, etc.). |

| Third-Party Transfer | Legally sanctioned sharing of “de-identified” data with research or commercial partners per the consent agreement. | Re-identification by the third party, or a subsequent breach of that third party’s systems. |

| Algorithmic Re-identification | Cross-referencing supposedly anonymous genetic data with other public or private datasets to uncover an individual’s identity. | Complete loss of anonymity, linking sensitive genetic predispositions to a named individual. |

| Law Enforcement Access | Companies complying with subpoenas or warrants for user data to identify suspects or their relatives. | Use of personal and familial genetic data for purposes outside of personal health and wellness. |

The Evolving Legal and Ethical Framework

The inadequacy of existing federal laws like HIPAA and GINA to fully address the consumer genetics market has led to a patchwork of state-level legislation. California’s Genetic Information Privacy Act (GIPA), for example, imposes stricter requirements on DTC companies, mandating express consent for data sharing and providing consumers with the right to access and delete their data.

These state-level efforts represent an attempt to close the regulatory gaps. However, a comprehensive federal privacy law that specifically governs consumer genetic data is still absent.

This situation raises profound ethical questions. The traditional model of “informed consent” is strained when the full implications of data sharing are unknowable at the time of consent. Can a person truly consent to the use of their data by future algorithms that have not yet been invented?

This has led some ethicists to propose alternative frameworks, such as a “data solidarity” model, where data is treated as a public good with robust, democratically controlled governance structures. These are the conversations that will shape the future of personalized medicine and data privacy.

References

- Frye, Hannah, et al. “Policy Memo ∞ Genetic Privacy Consumer Protections.” Washington University ProSPER, 16 Nov. 2020.

- “HIPAA compliance in direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing.” Paubox, 2 May 2024.

- “Personal and Social Issues – Direct-To-Consumer Genetic Testing.” NCBI Bookshelf, National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- “Privacy Best Practices for Consumer Genetic Testing Services.” Future of Privacy Forum, 31 Jul. 2018.

- Nations, Elisabeth. “Direct-to Consumer Genetic Testing Companies ∞ Is Genetic Data Adequately Protected in the Absence of HIPPA?” Business Law Digest, Wake Forest University School of Law, 19 Jan. 2023.

- Gymrek, M. et al. “Identifying personal genomes by surname inference.” Science, vol. 339, no. 6117, 2013, pp. 321-324.

- Erlich, Yaniv, et al. “Identity inference of genomic data using long-range familial searches.” Science, vol. 362, no. 6415, 2018, pp. 690-694.

- Vigna, Keithan. “Navigating the fallout ∞ 23andMe’s data breach and the ethics of consumer genetic testing.” The MEDucator, 2024.

- Shabani, M. and P. Borry. “Ethical Issues Associated With Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing.” Journal of Clinical Research & Bioethics, vol. 14, no. 3, 2023.

- “Data re-identification ∞ societal safeguards.” Science, vol. 339, no. 6125, 2013, pp. 1263-1264.

Reflection

You began this exploration seeking to understand your own biology on a deeper level. The knowledge you have gained about protecting your genetic data is a critical component of that journey. It is the framework that ensures your exploration remains your own. This information is not meant to create fear, but to build competence. It transforms you from a passive consumer into an informed steward of your own biological information.

Consider the information within these sections as a set of tools. The path forward is one of personal responsibility and continued learning. The questions you ask of a testing company, the choices you make about consent, and the digital hygiene you practice are all expressions of your commitment to your own well-being. Your genetic code is the most personal story ever written. The power to decide who gets to read it, and how, rests with you.

Glossary

your genetic data

genetic information

genetic data

genetic testing companies

genetic information nondiscrimination act

your genetic information

genetic testing

data brokerage

direct-to-consumer genetic testing

anonymization

surname inference

using long-range familial searches