Fundamentals

You track your steps, your sleep, your calories. You input data into an application on your phone, believing it is a private conversation between you and the technology. The information feels personal, a digital extension of your own body. A common understanding is that this data, when shared, is stripped of your name and address, rendered anonymous.

This process is called de-identification. The core idea is to remove direct identifiers ∞ like your name, social security number, or street address ∞ to protect your privacy. What is often misunderstood is that this de-identification is not a guarantee of anonymity. The digital breadcrumbs left behind, even after identifiers are removed, can paint a surprisingly detailed picture of who you are.

The information gathered by wellness applications often exists in a regulatory gray area. Many of these applications are not bound by the strict privacy rules of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the law that protects your medical records at a doctor’s office.

This means the data they collect can be legally bundled and sold. Third parties, from data brokers to advertising firms, can purchase these datasets. Their goal is to connect the dots. They might not know your name at first, but they can see a pattern ∞ a user in a specific zip code, of a certain age, with a particular sleep schedule and heart rate variability. By cross-referencing this with other available data, a process of re-identification can begin.

The Illusion of Anonymity

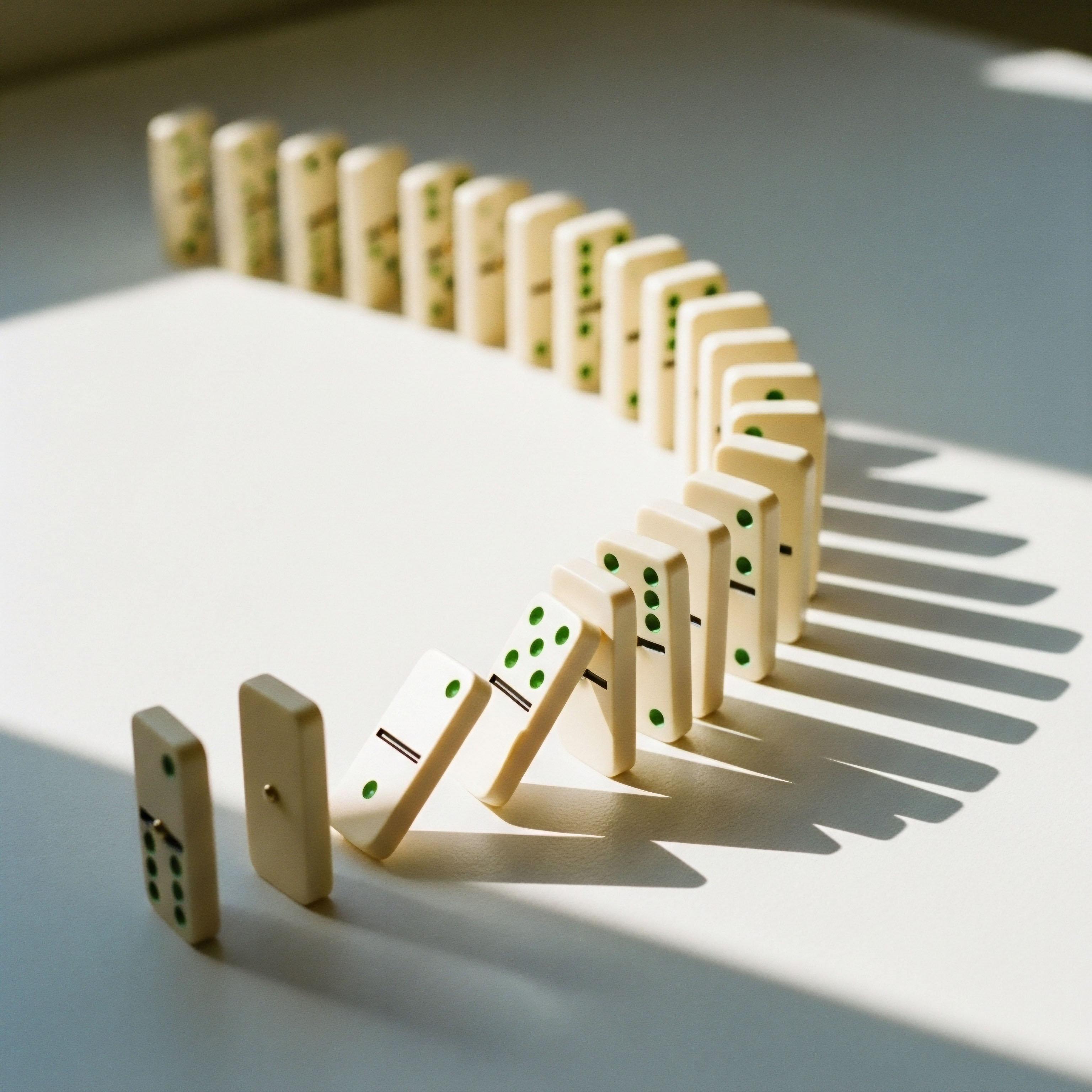

Imagine your de-identified data as a silhouette. Your name and face are gone, but the outline of your habits, your location data, and your health metrics remains. A single silhouette might be hard to identify in a crowd. When it is combined with other silhouettes, other datasets, the unique combination of your attributes can make you stand out.

For instance, your unique combination of zip code, birth date, and gender can be enough to re-identify a significant portion of the population. This is the central vulnerability. Your de-identified data is not just a single data point; it is a constellation of them. And in the world of big data, constellations are easy to spot.

Your de-identified wellness data can be reassembled by third parties to create a detailed, and identifiable, profile of your health and lifestyle.

This reality can feel like a betrayal of trust. You use these applications to better understand your own biology, to take control of your health. The discovery that this very personal information is being used for purposes you never intended, by entities you have never heard of, can be unsettling.

It underscores a fundamental disconnect between our perception of digital privacy and the mechanics of the data economy. The information you generate has value, and where there is value, there is a market.

What Happens to Your Data?

Once your de-identified data is sold, it enters a complex ecosystem. Advertisers might use it to target you with ads for specific health products or services. Insurance companies could potentially use it to build risk profiles. Pharmaceutical companies might analyze it to understand market trends for certain medications.

The applications of this data are vast and growing. The critical point is that these uses occur without your direct, ongoing consent for each specific application. The initial agreement, often buried in a lengthy terms-of-service document, is typically the only consent given. This is the landscape in which our personal health journeys are being silently monetized.

Intermediate

To appreciate how your de-identified data can be used, it is important to understand the technical and legal distinctions that govern data privacy. The primary regulation in the United States for health information is HIPAA, but its reach is limited.

It applies to “covered entities” like healthcare providers and insurers, and their “business associates.” Most wellness app developers do not fall into these categories. As a result, the data you provide them is not considered Protected Health Information (PHI) and is not subject to HIPAA’s stringent de-identification standards.

HIPAA outlines two methods for de-identifying data. The first, known as the “Safe Harbor” method, is a prescriptive approach that requires the removal of 18 specific identifiers. The second, the “Expert Determination” method, is more flexible and involves a statistical expert certifying that the risk of re-identification is very small.

Most wellness apps do not adhere to either of these standards. Their de-identification processes are often less rigorous, leaving behind a trail of “quasi-identifiers” that can be used to piece your identity back together.

The Mechanics of Re-Identification

How can data that has been stripped of your name and address still be traced back to you? The process of re-identification relies on a few key techniques. These methods are not theoretical; they are actively used by data scientists and analysts.

- Insufficient De-identification This occurs when a dataset still contains indirect identifiers. For example, a dataset might remove your name but leave in your zip code, your date of birth, and the make and model of your wearable device. This combination of factors can be unique enough to identify you.

- Pseudonym Reversal Some systems replace direct identifiers with a pseudonym, or a random code. If the key that links the pseudonym back to the original identifier is ever compromised or discovered, the entire dataset can be re-identified.

- Combining Datasets This is the most powerful re-identification technique. A de-identified dataset from a wellness app can be cross-referenced with other datasets, such as public voter registration files, social media data, or data from other breaches. By finding a common data point between two datasets ∞ like a zip code and a birthdate ∞ it is possible to link the de-identified health data to a specific person.

Who Are the Third Parties and What Do They Want?

The market for de-identified wellness data is diverse. Different third parties have different motivations for acquiring this information. Understanding these motivations clarifies why this data is so valuable.

| Third Party | Primary Use of Data | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Brokers | To aggregate and sell detailed consumer profiles. | Creating lists of individuals with specific health interests or conditions to sell to other companies. |

| Advertisers | To target individuals with specific ads. | Showing ads for sleep aids to users whose data indicates poor sleep patterns. |

| Pharmaceutical Companies | To conduct market research and post-market surveillance. | Analyzing data to understand the prevalence of certain symptoms or conditions in a population. |

| Insurance Companies | To assess risk and potentially inform pricing. | Using lifestyle data to build profiles that predict future health costs. |

| Research Institutions | To study health trends and disease patterns. | Analyzing large datasets to find correlations between lifestyle factors and health outcomes. |

The flow of data from your device to these third parties is often opaque. It happens through a series of transactions and data-sharing agreements that are not visible to the end user. This lack of transparency is a key feature of the current data economy.

The value of your de-identified data lies in its ability to predict your behavior and your health, making it a valuable commodity for a wide range of industries.

What Are the Implications for Your Health Journey?

The use of your de-identified data by third parties can have real-world consequences. Targeted advertising may seem benign, but it can also lead to what is known as “surveillance pricing,” where you are shown higher prices for goods or services based on your data profile.

The potential for this data to be used in decisions about insurance eligibility or premiums is a significant concern. While direct use of this data for such purposes may be regulated in some jurisdictions, the indirect influence of these data profiles is harder to track and control. Your personal quest for wellness can inadvertently become a data source for a commercial apparatus that may not have your best interests at heart.

Academic

The use of de-identified data from wellness applications by third parties operates in a complex and often ambiguous legal and ethical landscape. The central issue is the disconnect between the technical definition of “de-identified” and the practical reality of re-identification in a data-rich environment.

While regulatory frameworks like HIPAA provide a structured approach to de-identification, their limited applicability to consumer-facing wellness technologies creates a significant gap in oversight. This gap is exploited by a burgeoning data brokerage industry that thrives on the aggregation and analysis of consumer-generated data.

From a legal perspective, the primary recourse for consumers outside of HIPAA’s protection has been the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The FTC’s authority is generally limited to enforcing companies’ own privacy policies and taking action against deceptive practices.

If a company’s privacy policy states that it shares de-identified data with third parties, and it does so, there is often no legal violation, even if users were not fully aware of the implications. More recent legislation, such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), have introduced more robust definitions of personal data and de-identification, but their jurisdiction is not universal, and their effectiveness is still being evaluated.

The Fallacy of Anonymization in High-Dimensional Data

The concept of de-identification becomes increasingly tenuous as the dimensionality of the data increases. High-dimensional data, such as the continuous stream of information from a wearable device, is inherently more difficult to anonymize. A 2019 study in Nature Communications demonstrated that 99.98% of Americans could be correctly re-identified in any dataset using just 15 demographic attributes.

When you consider that wellness apps collect dozens of data points ∞ including geolocation, heart rate, sleep patterns, and even inferred emotional states ∞ the potential for re-identification becomes a near certainty.

The two methods of de-identification under HIPAA illustrate the challenge:

| De-identification Method | Description | Limitations in the Context of Wellness Apps |

|---|---|---|

| Safe Harbor | Removes 18 specific identifiers (name, address, etc.). | Does not account for the re-identification potential of high-dimensional, quasi-identifying data like location and biometric patterns. |

| Expert Determination | A statistical expert determines that the risk of re-identification is “very small.” | Relies on the expert’s assessment of the “anticipated recipient’s” ability to re-identify, which is difficult to predict in a world of data brokers and sophisticated AI. |

The very richness of the data that makes these apps useful for personal wellness also makes them a prime target for re-identification. The more data points collected, the more unique an individual’s “data signature” becomes, and the easier it is to single them out from a crowd.

Ethical Frameworks for Consumer-Generated Data

The ethical implications of this data trade are profound. The traditional model of informed consent, where a user agrees to a privacy policy once, is ill-suited for the continuous and evolving uses of their data. This has led to calls for new ethical frameworks for the use of consumer-generated data (CGD). These frameworks often emphasize principles like:

- Beneficence The use of data should be for the benefit of individuals and society.

- Non-maleficence The use of data should not cause harm, such as through discrimination or exploitation.

- Autonomy Individuals should have meaningful control over their data.

- Justice The benefits and risks of data use should be distributed fairly.

These principles challenge the current model, where the primary motivation for data use is often commercial profit. The concept of “dynamic consent,” where users are able to consent to or revoke permission for specific uses of their data on an ongoing basis, is one potential solution. However, implementing such a system at scale presents significant technical and logistical challenges.

The monetization of de-identified wellness data raises fundamental questions about data ownership, autonomy, and the potential for a new form of digital discrimination based on health-related behaviors.

What Is the Future of Health Data Privacy?

The ongoing proliferation of wellness technologies and the increasing sophistication of data analysis techniques suggest that the challenges to health data privacy will only grow. The legal and ethical frameworks are struggling to keep pace with the technology. This creates a situation where individuals are often unknowingly participating in a vast, unregulated market for their most personal information.

The path forward will likely require a combination of stronger legal protections, more transparent data practices from technology companies, and a greater awareness among individuals about the true value and vulnerability of their personal data. Without these changes, the personal journey toward wellness will continue to be a source of raw material for a data economy that operates largely in the shadows.

References

- Humer, C. & Stabauer, M. (2019). Re-identifiability of public data. Nature Communications, 10(1), 1-3.

- Majumder, M. A. & Guerrini, C. J. (2021). Privacy protections to encourage use of health-relevant digital data in a learning health system. NAM Perspectives.

- IS Partners, LLC. (2023). Data Privacy at Risk with Health and Wellness Apps.

- Georgetown Law Technology Review. (2017). Re-Identification of “Anonymized” Data.

- The HIPAA Journal. (2023). De-identification of Protected Health Information.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Ethical considerations and data protection principles.

- Granger, E. & Mbawuike, S. (2019). An Ethical Framework for the Use of Consumer-Generated Data in Health Care. MITRE.

- Price, W. N. & Cohen, I. G. (2019). Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 37-43.

- Shabani, M. & Marelli, L. (2019). The ethical debate about the privacy of health data ∞ a reality check in the age of big data. Annals of Internal Medicine, 170(7), 489-490.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism ∞ The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs.

Reflection

What Does Your Data Signature Reveal?

The information you have gathered here is not meant to induce fear, but to foster a deeper awareness. Your personal health data is more than just numbers on a screen; it is a digital echo of your life. It tells a story about your habits, your struggles, and your triumphs.

As you continue on your path to wellness, consider the nature of this story. Who gets to read it? For what purpose? The answers to these questions are not simple, and they are constantly evolving with technology and legislation. Your journey is your own, but the data it generates is part of a much larger ecosystem. Understanding your place in that ecosystem is a powerful step toward reclaiming not just your physical vitality, but your digital autonomy as well.

Glossary

hipaa

re-identification

third parties

your de-identified data

de-identified data

data privacy

wellness apps

health data

de-identified wellness data

surveillance pricing

targeted advertising

consumer-generated data

ethical frameworks