Fundamentals

You may be reading this because you feel a distinct shift in your own body. Perhaps it’s a subtle loss of energy, a change in mood, or a diminished sense of vitality that you can’t quite name. These feelings are valid, and they often point toward underlying changes in your body’s intricate internal communication network, the endocrine system.

At the heart of this system for men is testosterone. When its levels decline, the effects are felt system-wide. The conversation around restoring these levels through Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) often, and understandably, turns to a significant question ∞ what about the prostate?

The concern stems from a logical, yet ultimately incomplete, understanding of how testosterone interacts with prostate tissue. For decades, the medical field operated on a simplified model where testosterone was seen as direct fuel for prostate cancer growth. This idea originated from landmark studies in the 1940s involving men with advanced, metastatic prostate cancer.

In these specific cases, drastically lowering testosterone did indeed slow the cancer’s progression. This led to the inference that raising testosterone would have the opposite effect, accelerating or even causing prostate cancer. This perspective, while born from crucial initial observations, has been substantially refined by decades of subsequent clinical research.

A more current and evidence-based view shows that the relationship between testosterone and prostate health is one of saturation, where prostate tissue can only respond to a certain amount of testosterone before becoming unresponsive to further increases.

To understand this better, let’s use an analogy. Imagine your prostate cells are like a small engine. When the engine has no fuel (very low testosterone), it doesn’t run. If you add a small amount of fuel, the engine starts and its speed increases.

But once the fuel line is full, adding more gasoline to the tank won’t make the engine run any faster. It has reached its maximum capacity. Prostate tissue behaves in a similar way. In a state of severe testosterone deficiency (hypogonadism), the cells are “starved.” Introducing testosterone via TRT brings levels back to a normal, healthy range, effectively “refueling” the engine.

For most men, their prostate tissue is already fully saturated with testosterone at a level far below the normal physiological range. Therefore, bringing testosterone from a low level up to a normal or even high-normal level does not provide additional “fuel” for cancer growth because the tissue’s capacity to respond is already maxed out. This is the core of what is known as the Prostate Saturation Model.

This refined understanding helps explain why numerous large-scale studies and meta-analyses ∞ which pool the data from many individual clinical trials ∞ have consistently failed to show a direct causal link between TRT and the development of prostate cancer.

The evidence points toward a conclusion that for men with clinically diagnosed hypogonadism, restoring testosterone to a normal physiological state does not inherently increase the risk of initiating prostate cancer. The conversation in modern endocrinology and urology has moved toward a more sophisticated view of risk management, monitoring, and patient selection, grounded in this saturation principle.

Intermediate

As we move beyond the foundational concepts, it becomes essential to examine the clinical protocols that govern the responsible application of hormonal optimization therapies. Understanding how a qualified practitioner approaches Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) illuminates the built-in safeguards and monitoring strategies that directly address prostate health. The goal of a well-designed protocol is to restore physiological balance, and this process inherently involves a meticulous approach to risk mitigation through both preliminary screening and ongoing surveillance.

Pre-Therapy Risk Stratification

Before a single prescription is written, a thorough evaluation of prostate health is a mandatory step. This is a critical aspect of personalized wellness protocols. The process begins with a baseline assessment, which serves two primary functions ∞ it establishes a patient’s existing prostate health status and identifies any underlying conditions that might require further investigation before hormonal therapy can be considered. This initial workup is a cornerstone of safe and effective treatment.

The key components of this baseline assessment typically include:

- Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test ∞ A blood test that measures the level of PSA, a protein produced by the prostate gland. While elevated PSA can be an indicator of prostate cancer, it is also raised by benign conditions like Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) or prostatitis. A baseline level is crucial for tracking changes over time.

- Digital Rectal Exam (DRE) ∞ A physical examination that allows the clinician to assess the size, shape, and texture of the prostate gland, checking for any nodules, hardness, or irregularities that could warrant further evaluation.

An elevated PSA or an abnormal DRE finding at this stage triggers a referral to a urologist. Hormonal therapy is typically deferred until a complete urological workup is finished, which may include advanced imaging or a prostate biopsy, to rule out an existing cancer. This ensures that TRT does not commence in an individual with an undiagnosed, pre-existing prostate malignancy.

Monitoring Protocols during Therapy

Once therapy begins, monitoring becomes the central pillar of long-term safety. The endocrine system is dynamic, and the body’s response to hormonal recalibration must be tracked. Regular follow-up appointments with specific lab work are standard practice. This systematic approach allows for the early detection of any changes in prostate health, facilitating prompt intervention if needed.

Systematic monitoring of PSA levels and regular clinical evaluations are integral to modern TRT protocols, ensuring prostate health is actively tracked throughout the treatment process.

The table below outlines a typical monitoring schedule, though individual frequency may be adjusted based on a patient’s specific risk profile and clinical history.

| Time Point | Key Assessments | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Pre-TRT) | Total & Free Testosterone, Estradiol, PSA, DRE | Establish initial hormonal and prostate health status. |

| 3-6 Months Post-Initiation | PSA, Hematocrit, Hormonal Panel | Assess initial response and check for early changes in PSA. |

| 12 Months Post-Initiation | PSA, DRE, Hormonal Panel | Evaluate one-year prostate status and overall response. |

| Annually Thereafter | PSA, DRE, Hematocrit, Hormonal Panel | Conduct ongoing, long-term surveillance of prostate health. |

Interpreting Changes in PSA on TRT

It is understood that initiating TRT can cause a modest, one-time increase in PSA levels in some men. This is generally considered a physiological effect of restoring testosterone in previously hypogonadal tissue and is not, in itself, an indicator of malignancy. The critical factor is the pattern of change.

A small, initial rise that then stabilizes is typically of low concern. In contrast, a continuous, significant rise in PSA velocity (the rate of increase over time) would trigger a prompt urological evaluation. This nuanced interpretation of PSA dynamics is a key skill in managing patients on hormonal optimization protocols.

One study found that while TRT was associated with a higher detection of favorable-risk prostate cancer, it was also linked to a lower risk of aggressive prostate cancer, particularly after more than a year of use.

This suggests that increased medical surveillance in men on TRT may lead to earlier detection of low-grade cancers that might have otherwise gone unnoticed, while potentially having a protective effect against more dangerous forms of the disease. The evidence from multiple meta-analyses supports the conclusion that TRT, when administered and monitored correctly, does not increase the overall incidence of prostate cancer.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the interplay between testosterone administration and prostate cancer requires moving beyond population-level statistics and into the realm of cellular biology and endocrine physiology. The historical apprehension surrounding Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) was built upon a foundational, yet incomplete, androgen hypothesis.

A deeper, more mechanistic investigation reveals a complex, non-linear relationship governed by principles of receptor saturation and cellular differentiation. This section explores the molecular underpinnings of the testosterone-prostate relationship and examines the clinical data through a systems-biology lens.

The Androgen Receptor Saturation Model

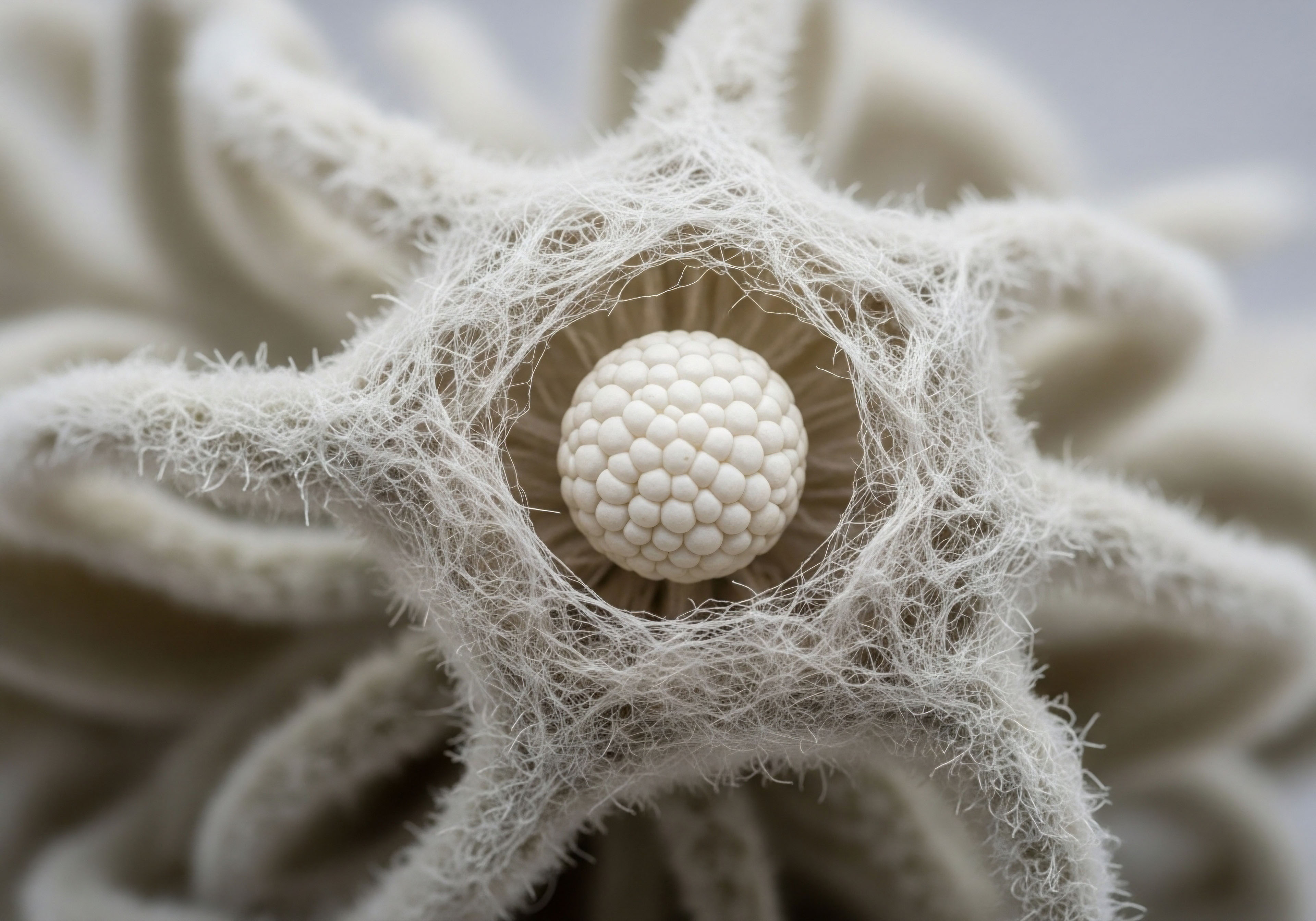

The central tenet that reframes our understanding is the Androgen Receptor (AR) Saturation Model. Prostate cells, both benign and malignant, express a finite number of androgen receptors. These receptors are the molecular docking stations for testosterone and its more potent metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT). The biological activity stimulated by androgens, such as gene transcription leading to cell growth and PSA production, is dependent on the binding of these hormones to their receptors.

Research has demonstrated that these androgen receptors become fully saturated at relatively low serum testosterone concentrations. Studies suggest that maximal androgen-receptor binding within the prostate occurs at testosterone levels of approximately 200-250 ng/dL. In men with hypogonadism, serum testosterone is, by definition, significantly below this threshold.

Initiating TRT elevates serum testosterone from a deficient state into the normal physiological range (typically 300-1000 ng/dL). This increase restores maximal binding to the androgen receptors. However, once this saturation point is reached, further increases in serum testosterone do not yield a proportional increase in androgenic activity within the prostate tissue.

The system’s capacity for response is already maximized. This explains why raising testosterone from 150 ng/dL to 500 ng/dL produces a biological effect, but raising it from 500 ng/dL to 900 ng/dL does not further stimulate prostate tissue that is already saturated.

What Is the Connection between Low Testosterone and Aggressive Cancer?

Paradoxically, a growing body of evidence suggests that a state of chronic low testosterone may be associated with a more aggressive prostate cancer phenotype. This seemingly counterintuitive finding has several proposed biological explanations. One hypothesis centers on the concept of cellular differentiation. Androgens like testosterone are crucial for the maturation and differentiation of normal prostate epithelial cells.

In a low-androgen environment, prostate cells may become poorly differentiated. These less-differentiated cells are often more aggressive and have a higher metastatic potential when they do become cancerous. Therefore, a chronically hypogonadal state might foster an intraprostatic environment conducive to the development of higher-grade tumors.

Another layer of complexity involves the characteristics of the androgen receptor itself. Some research indicates that in a low-testosterone environment, prostate cancer cells may adapt by upregulating the expression of androgen receptors or developing mutations that make these receptors hypersensitive to even minuscule amounts of circulating androgens. This adaptive mechanism could contribute to the development of more aggressive, treatment-resistant cancers over time.

The biological evidence indicates that once androgen receptors in the prostate are saturated, supraphysiological increases in testosterone do not confer additional cancer risk, challenging the outdated linear risk model.

Clinical Evidence from Large Scale Analyses

This molecular understanding is strongly supported by large-scale clinical data. Multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which represent the highest level of clinical evidence, have consistently failed to demonstrate a causal link between TRT and an increased risk of developing prostate cancer.

A meta-analysis of 22 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found no statistically significant increase in prostate cancer incidence with either short-term or long-term TRT, regardless of the administration method (injection, transdermal, or oral). Another comprehensive review similarly concluded that TRT does not appear to alter prostate cancer risk.

The table below summarizes findings from key meta-analyses, highlighting the consistency of the data across different study populations and timeframes.

| Study Focus | Number of Included Studies | Key Finding Regarding Prostate Cancer Risk | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs | 22 RCTs | No statistically significant increase in prostate cancer risk with short-term or long-term TRT. | |

| Retrospective cohort study with long-term follow-up | 1 cohort (20 years) | No increased risk of prostate cancer was identified in men on long-term testosterone treatment. | |

| Population-based case-control study | N/A (Register Data) | TRT was associated with a decreased risk of aggressive prostate cancer. | |

| Meta-analysis including RCTs and observational studies | 15 studies | Low testosterone levels, not TRT, were associated with a slightly increased risk of prostate cancer. |

This convergence of molecular science and clinical epidemiology provides a robust framework for concluding that for appropriately selected and monitored hypogonadal men, testosterone replacement therapy does not increase the risk of prostate cancer. The focus of clinical concern has rightfully shifted toward the potential risks associated with untreated, chronic hypogonadism.

References

- Cui, Y. et al. “The effect of testosterone replacement therapy on prostate cancer ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases, vol. 17, no. 2, 2014, pp. 132-43.

- Lokeshwar, S. D. et al. “Testosterone Replacement Therapy and Prostate Cancer Incidence.” Urologic Clinics of North America, vol. 42, no. 3, 2015, pp. 351-8.

- Loeb, S. et al. “Testosterone Replacement Therapy and Risk of Favorable and Aggressive Prostate Cancer.” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 35, no. 13, 2017, pp. 1430-6.

- Marino, P. “Meta-Analysis ∞ Is There a Correlation Between Testosterone Therapy and Prostate Cancer?” Medium, 10 Sept. 2024.

- Zhao, J. et al. “An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of testosterone replacement therapy on erectile function and prostate.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 15, 2024.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a detailed map of the current scientific and clinical landscape. It traces the journey from an outdated, simplified fear to a sophisticated, evidence-based understanding of hormonal health. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It allows you to reframe the conversation you have with yourself, and with your healthcare provider, about your own vitality and well-being. The data and mechanisms explored are designed to build a foundation of clarity, replacing apprehension with informed confidence.

Your personal health narrative is unique. The symptoms you feel, the goals you have, and your individual biology create a context that no study or statistic can fully capture. The true value of this clinical knowledge is realized when it is applied to your specific situation.

Consider how these concepts intersect with your own experience. What questions have been answered? More importantly, what new questions have arisen for you about your own path forward? This exploration is the beginning of a proactive partnership with your own body, one where understanding its intricate systems becomes the key to optimizing its function for the long term.