Fundamentals

You may have a persistent feeling that the landscape of health has changed, particularly for children. Conditions that once seemed uncommon are now part of our regular conversation. This experience is valid, and the reasons for it are woven into the very fabric of our modern environment.

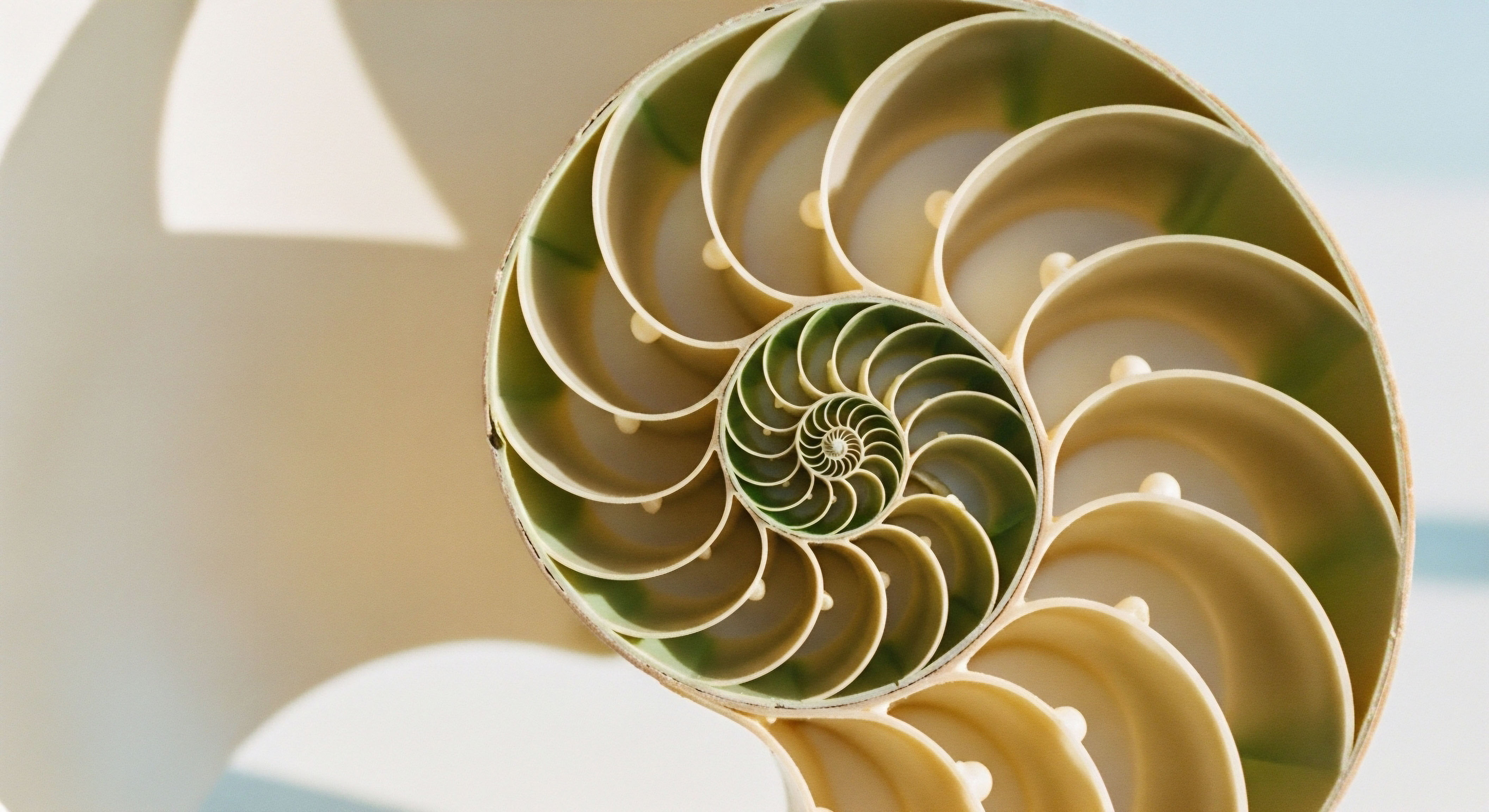

The answers begin not with a single diagnosis, but with an understanding of the body’s most essential communication system ∞ the endocrine network. This intricate web of glands and hormones directs growth, metabolism, mood, and reproductive function from the first moments of life.

It operates with precision, sending chemical messages that act as a biological blueprint for development. When this communication is clear, the body builds itself according to its genetic instructions, leading to robust health. The challenge of our time is that this system is now constantly exposed to external signals that can interfere with its carefully orchestrated processes.

The Body’s Internal Messaging System

Your endocrine system is the silent conductor of your body’s orchestra. It comprises glands like the thyroid, adrenals, pituitary, and gonads, which produce hormones. These hormones are potent chemical messengers that travel through the bloodstream to target cells, where they lock onto specific receptors to deliver instructions.

This process governs everything from your energy levels and how you store fat to your stress response and reproductive cycles. Think of it as a highly secure, specific postal service. A hormone is a letter, the bloodstream is the mail carrier, and the cellular receptor is the specific mailbox it is designed to fit. When this system functions correctly, the right messages are delivered to the right places at the right times, ensuring seamless biological function and development.

What Are Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are substances in our environment that can interfere with this vital messaging service. They are found in a vast array of everyday products, including plastics, food packaging, personal care products, pesticides, and household dust.

Because of their chemical structure, they can mimic the body’s natural hormones, block their action, or alter how they are made, transported, and broken down. This interference can be compared to receiving counterfeit mail, having your mailbox blocked, or the post office losing your letters. The result is a miscommunication within the body’s control systems. The developing body of a child, which relies on precise hormonal signals for its construction, is especially sensitive to this kind of signal disruption.

A Blueprint for Life the Developmental Origins of Health

A foundational concept in understanding the long-term effects of early environmental exposures is the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis. This framework explains that the environment experienced during critical periods of development, such as in the womb and in early childhood, establishes a blueprint for health throughout an individual’s entire life.

During these windows, the body’s systems are highly plastic, adapting to the signals they receive from the outside world. Exposure to EDCs during these formative stages can alter the developmental trajectory of organs and systems, creating a predisposition for certain health outcomes that may only become apparent years or even decades later.

The environment in which a child develops can program their biological systems, influencing their health and disease risk for the rest of their life.

This means that conditions like metabolic disorders, reproductive issues, and certain cancers in adulthood may have their roots in exposures that occurred before birth or during infancy. The DOHaD model moves our perspective from simply treating adult diseases to understanding and mitigating the early-life factors that contribute to them.

It underscores the profound importance of protecting the integrity of the endocrine system during its most formative stages. The signals a developing fetus and child receive help calibrate their metabolic and hormonal systems for life. When disruptive chemicals are part of that signaling environment, the calibration can be set incorrectly.

Why Are Children Uniquely Vulnerable?

A child’s body is a site of continuous, rapid development, making it uniquely susceptible to the effects of endocrine disruptors. Their vulnerability is a matter of biology and behavior, creating a situation of heightened risk compared to adults. Several factors contribute to this increased sensitivity.

- Developmental State ∞ Children are not little adults. Their organ systems, including the brain, reproductive organs, and metabolic machinery, are still under construction. The hormonal signals guiding this development are exquisitely timed and dosed, and even minor interference can have permanent consequences.

- Higher Relative Exposure ∞ On a pound-for-pound basis, children breathe more air, drink more water, and eat more food than adults. This means they experience a higher relative dose of any contaminants present in their environment.

- Unique Behaviors ∞ Young children explore the world with their hands and mouths. This normal developmental behavior increases their ingestion of chemicals found in dust, soil, and on the surfaces of toys and other household objects.

- Immature Detoxification Systems ∞ The liver and kidneys, which are responsible for breaking down and eliminating foreign chemicals from the body, are not fully mature in infants and young children. This means that EDCs may stay in their bodies for longer periods and at higher concentrations.

These combined factors create a window of susceptibility where even low-dose exposures to EDCs can have significant and lasting health implications. The consequences may manifest as observable changes in pubertal timing, neurodevelopmental challenges, or a heightened risk for metabolic conditions like obesity and diabetes later in life. Understanding this unique vulnerability is the first step toward creating a safer environment for development.

Intermediate

To truly grasp how environmental chemicals influence childhood development, we must move from the general concept of interference to the specific biological mechanisms at play. EDCs operate with a subtlety that belies their impact, leveraging the body’s own communication pathways to deliver disruptive messages.

Their effects are a direct consequence of their ability to interact with the cellular machinery that regulates hormonal balance. By examining these mechanisms, we can understand how exposure translates into the observable health outcomes seen in clinical and population studies. The story of endocrine disruption is one of mistaken identity, blocked signals, and altered conversations at the most fundamental level of our biology.

Mechanisms of Disruption How Signals Get Crossed

Endocrine disruptors do not typically cause direct, acute toxicity in the way a classic poison might. Their power lies in their ability to manipulate the endocrine system’s intricate feedback loops. They can act in several primary ways, each with distinct consequences for hormonal health. These mechanisms explain how a chemical in a plastic bottle or a pesticide residue on food can ultimately alter the course of pubertal development or metabolic function.

Agonists and Antagonists Unwanted Messages

One of the most direct ways EDCs interfere with the endocrine system is by binding to hormone receptors. Receptors are protein structures on or inside cells, shaped to receive a specific hormone, much like a lock and key. When an EDC mimics a natural hormone and activates its receptor, it is called an agonist.

The cell is tricked into responding as if it received a signal from the body’s own hormone. For example, some chemicals act as estrogen agonists, promoting estrogenic activity. Conversely, when an EDC binds to a receptor but fails to activate it, instead physically blocking the natural hormone from binding, it is called an antagonist.

This prevents the intended message from being received. For instance, chemicals with anti-androgenic effects can block testosterone from delivering its signals, which is particularly consequential during male fetal development.

Altering Hormone Pathways Changing the Conversation

Beyond direct receptor interaction, EDCs can disrupt the entire lifecycle of a hormone. This includes its synthesis, transportation, metabolism, and excretion. They can inhibit or ramp up the production of enzymes responsible for creating or breaking down hormones. For example, some chemicals can interfere with thyroid peroxidase, an enzyme essential for producing thyroid hormone.

This leads to a lower level of available thyroid hormone, which is critical for brain development and metabolism. Others can affect the proteins that carry hormones through the bloodstream, altering the amount of hormone that is available to the body’s tissues. This systemic interference changes the entire hormonal conversation, creating an imbalance that the body’s feedback loops may struggle to correct.

| Chemical Class | Common Sources | Primary Mechanism of Action | Associated Health Outcomes in Children |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Lining of food and beverage cans, thermal paper receipts, some plastics | Estrogen receptor agonist, androgen receptor antagonist, thyroid pathway disruption | Altered pubertal timing, increased risk of obesity, behavioral issues. |

| Phthalates | Soft plastics, vinyl flooring, personal care products (fragrances), medical tubing | Primarily anti-androgenic; interferes with testosterone synthesis | Testicular dysgenesis syndrome, reduced anogenital distance in boys, altered pubertal timing. |

| Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) | Flame retardants in furniture, electronics, and textiles | Thyroid hormone disruption, altered steroid hormone levels | Lower birth weight, impaired neurodevelopment and IQ. |

| Pesticides (e.g. Organophosphates, Atrazine) | Agriculture, residential lawn care, insect control | Varies; can inhibit key enzymes, alter steroid hormone production | Neurodevelopmental deficits, potential effects on reproductive health. |

The Impact on Key Developmental Pathways

During childhood, several biological systems are undergoing intense and precisely scheduled development. These are the windows of greatest sensitivity, where endocrine disruption can leave a lasting mark. The effects are not random; they correlate directly with the role of the hormonal system being disrupted.

The specific health effect of an endocrine disruptor often reflects the function of the hormonal pathway it targets.

Thyroid Function the Body’s Metabolic Thermostat

Thyroid hormones are master regulators of metabolism and are absolutely essential for normal brain development, particularly in utero and during the first few years of life. EDCs like PCBs and PBDEs are structurally similar to thyroid hormones and can interfere with their production, transport, and action.

This disruption can lead to sub-optimal thyroid function, which has been linked in studies to lower IQ scores, attention deficits, and other neurodevelopmental challenges. Because the thyroid also sets the body’s metabolic rate, its disruption during development can also contribute to problems with weight regulation later in life.

Reproductive Development and Pubertal Timing

The development of the reproductive system is a process exquisitely sensitive to sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen. Exposure to EDCs with anti-androgenic or estrogenic properties during fetal development can alter the formation of reproductive organs. One manifestation of this is the “testicular dysgenesis syndrome” (TDS) hypothesis, which connects early EDC exposure to a spectrum of male reproductive issues.

- Exposure ∞ A male fetus is exposed to anti-androgenic chemicals (like certain phthalates) during a critical window of gonadal development.

- Interference ∞ These chemicals disrupt testosterone synthesis or action within the developing testes.

- Outcome at Birth ∞ This can lead to observable conditions like hypospadias (an abnormal placement of the urethral opening) or cryptorchidism (undescended testes).

- Later Life Consequences ∞ The underlying testicular dysfunction may persist, leading to reduced sperm quality and an increased risk for testicular cancer in adulthood.

In both boys and girls, EDCs can also alter the timing of puberty. Chemicals that mimic estrogen can contribute to precocious (early) puberty in girls, while others that disrupt hormonal axes can lead to delayed puberty. These changes are a visible sign that the body’s internal clock has been recalibrated by external chemical signals.

Metabolic Health and Obesity the Emerging Picture

The global increase in childhood obesity and type 2 diabetes has prompted researchers to investigate environmental contributors. A class of EDCs known as “obesogens” are chemicals that promote obesity by altering metabolic programming. They can do this by increasing the number and size of fat cells, changing the body’s regulation of appetite and satiety, and altering the basal metabolic rate.

Exposures to obesogens like BPA and certain phthalates during early development can program the body to be more efficient at storing energy as fat, predisposing an individual to weight gain and metabolic syndrome throughout their life.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of how environmental disruptors shape long-term health requires moving beyond direct mechanistic effects to the level of cellular programming. The most profound and lasting impacts of EDCs are often mediated through epigenetics. Epigenetic modifications are chemical tags that attach to our DNA, acting as a set of instructions that tell our genes when to turn on and off.

These modifications do not change the DNA sequence itself, but they govern how the genetic code is expressed. Early-life exposure to EDCs can alter these epigenetic patterns, particularly within the sensitive control systems that govern hormonal balance, such as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This reprogramming can establish a new, and potentially dysfunctional, hormonal baseline that persists for a lifetime.

Epigenetic Reprogramming of the HPG Axis

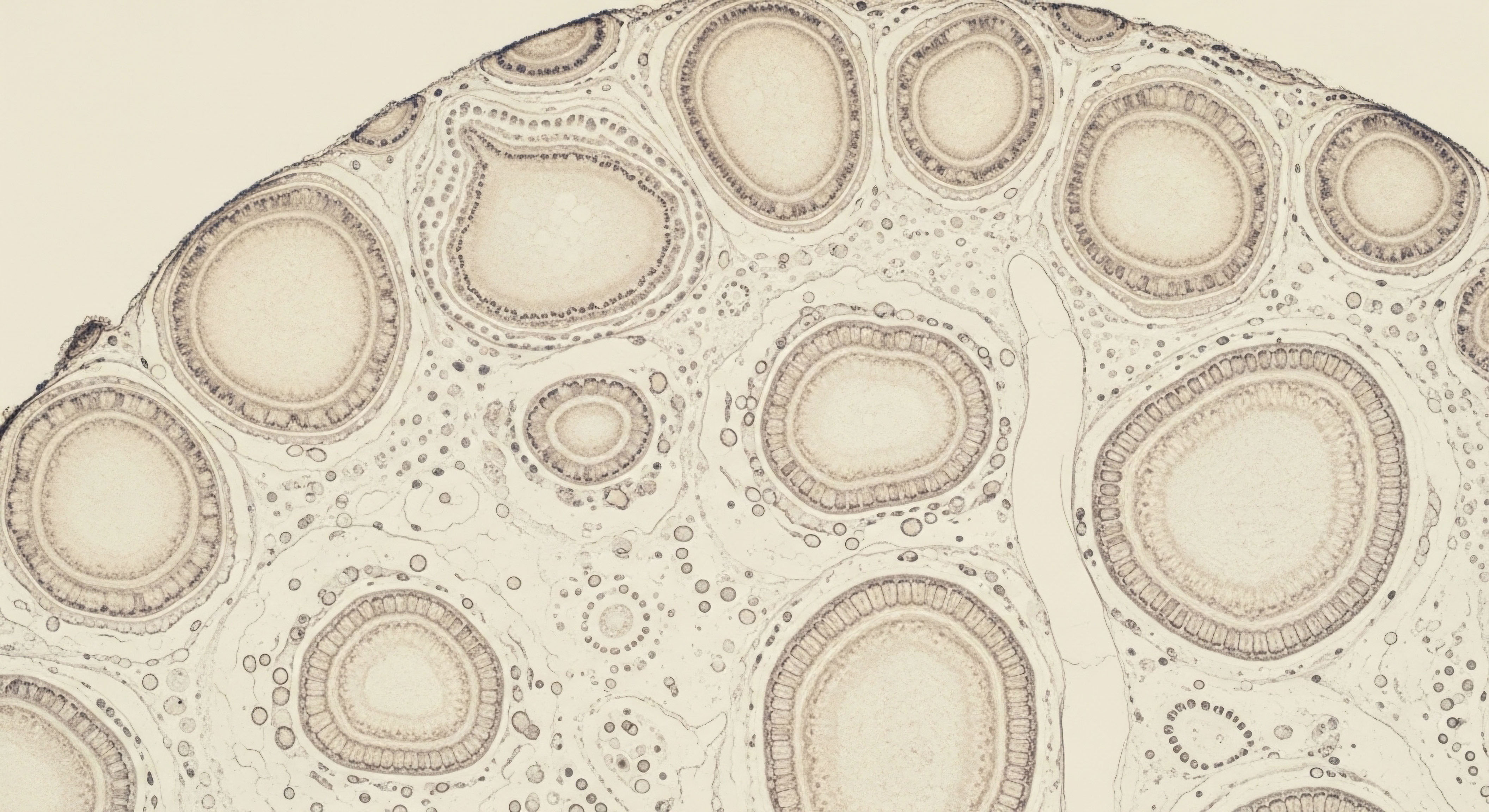

The HPG axis is a cornerstone of reproductive health and endocrine function. It is a complex feedback loop involving the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the gonads (testes or ovaries). The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

These hormones, in turn, signal the gonads to produce sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen. This axis is finely tuned by feedback from the sex hormones themselves. Epigenetic marks established during fetal and neonatal development play a crucial role in calibrating the sensitivity and responsiveness of this axis.

How Do EDCs Alter Genetic Expression?

EDCs can induce epigenetic changes through several key mechanisms, including DNA methylation and histone modification. DNA methylation involves adding a methyl group to a specific site on the DNA, which typically acts to silence gene expression. Histone modification involves altering the proteins that DNA is wrapped around, making genes more or less accessible for transcription.

During critical developmental windows, when these epigenetic patterns are being established, the presence of EDCs can cause aberrant methylation or histone modifications in the genes that control the HPG axis. For example, an EDC could cause the gene for the estrogen receptor to be inappropriately silenced or over-expressed, permanently altering that tissue’s sensitivity to estrogen. These changes, once set, can be remarkably stable and are a primary mechanism through which early exposures exert lifelong effects.

Epigenetic modifications induced by early-life EDC exposure can permanently alter the operational set-points of the body’s hormonal control systems.

This provides a biological explanation for how a transient exposure during pregnancy can lead to a persistent condition like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or low testosterone in an adult male decades later. The chemical is long gone, but the epigenetic instructions it left behind continue to direct the body’s function.

Case Study Bisphenol a and Its Generational Impact

Bisphenol A (BPA) is one of the most studied EDCs, and research provides a clear example of how these principles operate. BPA is a weak estrogen agonist but has been shown to have potent effects on developmental programming, particularly through epigenetic mechanisms. Animal studies have demonstrated that perinatal exposure to BPA can alter the DNA methylation patterns of genes critical to HPG axis function, leading to a range of reproductive disorders in offspring that persist into adulthood.

| Study Focus | Key Findings | Implication for Human Health |

|---|---|---|

| Female Reproductive Cycling | Perinatal BPA exposure in animal models is linked to altered methylation of GnRH neurons, leading to irregular estrous cycles and anovulation in adult females. | Provides a potential mechanism for the observed association between BPA exposure and conditions like PCOS in women. |

| Male Reproductive Function | Developmental BPA exposure has been shown to decrease the expression of key steroidogenic enzymes in the testes through epigenetic silencing. | Correlates with findings of reduced sperm quality and lower testosterone levels in human populations with high BPA exposure. |

| Pubertal Onset | BPA exposure can advance the age of vaginal opening (a marker of puberty) in female rodents, associated with changes in hypothalamic gene expression. | Supports epidemiological data suggesting a link between BPA and early puberty in girls. |

What Are the Long Term Consequences for Adult Hormonal Health?

The epigenetic reprogramming of the HPG axis during childhood development has direct and significant consequences for adult endocrinology. The altered hormonal milieu established in early life becomes the “new normal” for that individual, often leading to a state of sub-optimal function or overt disease that requires clinical intervention. This perspective is vital for understanding the root causes of many common adult endocrine disorders.

Implications for Female Reproductive Health

For women, early-life EDC exposure is increasingly implicated in the pathophysiology of several conditions. A reprogrammed HPG axis can lead to the hormonal imbalances characteristic of PCOS, including elevated androgens and insulin resistance. It may also contribute to endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and fertility challenges.

The developmental programming of the HPG axis can influence the entire reproductive lifespan, from the timing of menarche to the experience of perimenopause and the age of menopause. Understanding a patient’s potential developmental exposures can provide a deeper context for managing these conditions.

Implications for Male Endocrine Function

For men, the consequences of a developmentally disrupted HPG axis often manifest as primary or secondary hypogonadism later in life. The worldwide trend of declining testosterone levels and sperm quality over the past several decades is a subject of intense scientific investigation, with EDCs being a primary suspect.

An HPG axis that was epigenetically programmed for lower testosterone production during development will result in an adult male who experiences symptoms of low testosterone, such as fatigue, low libido, and loss of muscle mass, at an earlier age.

This provides a clear rationale for the clinical protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) combined with agents like Gonadorelin to support the HPG axis, which are designed to restore hormonal balance in adults whose systems may have been compromised decades earlier.

References

- Di Ciaula, Agostino, and Piero Portincasa. “Endocrine Disruptor Chemicals and Children’s Health.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 3, Jan. 2023, p. 2759.

- Kamboj, Stacie, and Tzel-Po Chen. “Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Children.” Pediatrics in Review, vol. 45, no. 2, Feb. 2024, pp. 71-80.

- Meeker, John D. “Exposure to Environmental Endocrine Disruptors and Child Development.” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, vol. 166, no. 10, Oct. 2012, pp. 952-58.

- Fucic, Aleksandra, et al. “Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals’ Effects in Children ∞ What We Know and What We Need to Learn?” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 15, Aug. 2022, p. 8559.

- Miller, M. D. et al. “Thyroid-disrupting chemicals ∞ interpreting upstream biomarkers of adverse outcomes.” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 117, no. 7, 2009, pp. 1033-41.

- Grandjean, Philippe, and Philip J. Landrigan. “Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals.” The Lancet, vol. 368, no. 9553, 2006, pp. 2167-78.

- Soto, Ana M. and Carlos Sonnenschein. “Environmental causes of cancer ∞ endocrine disruptors as carcinogens.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 6, no. 7, 2010, pp. 363-70.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Path

The information presented here provides a map, connecting the subtle environmental exposures of early life to the tangible health experiences of adulthood. This map is built from decades of scientific inquiry, offering a clear biological narrative for how development can be influenced. Yet, a map is only a guide.

It shows the terrain, but you are the one who must navigate it. Understanding that your body’s intricate hormonal systems were architected in an environment filled with disruptive signals is a profound realization. It shifts the focus from a place of passive reaction to one of proactive engagement with your own biology.

This knowledge is the starting point for a different kind of health conversation. It is a conversation based on understanding your unique physiology, interpreting the signals your body is sending you now, and using targeted strategies to support and recalibrate your endocrine function.

The goal is to move toward a state of optimized health, where your body’s internal communication is clear, and its systems are functioning in concert. Your personal health path is yours to chart, and it begins with the decision to understand the forces that have shaped your biology and the tools available to help you reclaim your vitality.