Fundamentals

You have followed the rules, meticulously. You track your calories, schedule high-intensity workouts, and prioritize sleep. Yet, the scale remains stubborn, brain fog clouds your afternoons, and a persistent layer of fat clings to your midsection. The vitality you were promised feels further away than ever.

This experience, a frustrating paradox of modern wellness, is a biological reality for many. The very pressure to achieve a state of perfect health can become a potent physiological stressor, initiating a cascade of events within your body that actively works against your goals. The issue is rooted in the body’s ancient survival wiring, a system that cannot distinguish between the threat of a predator and the perceived threat of a punishing diet or a relentless workout schedule.

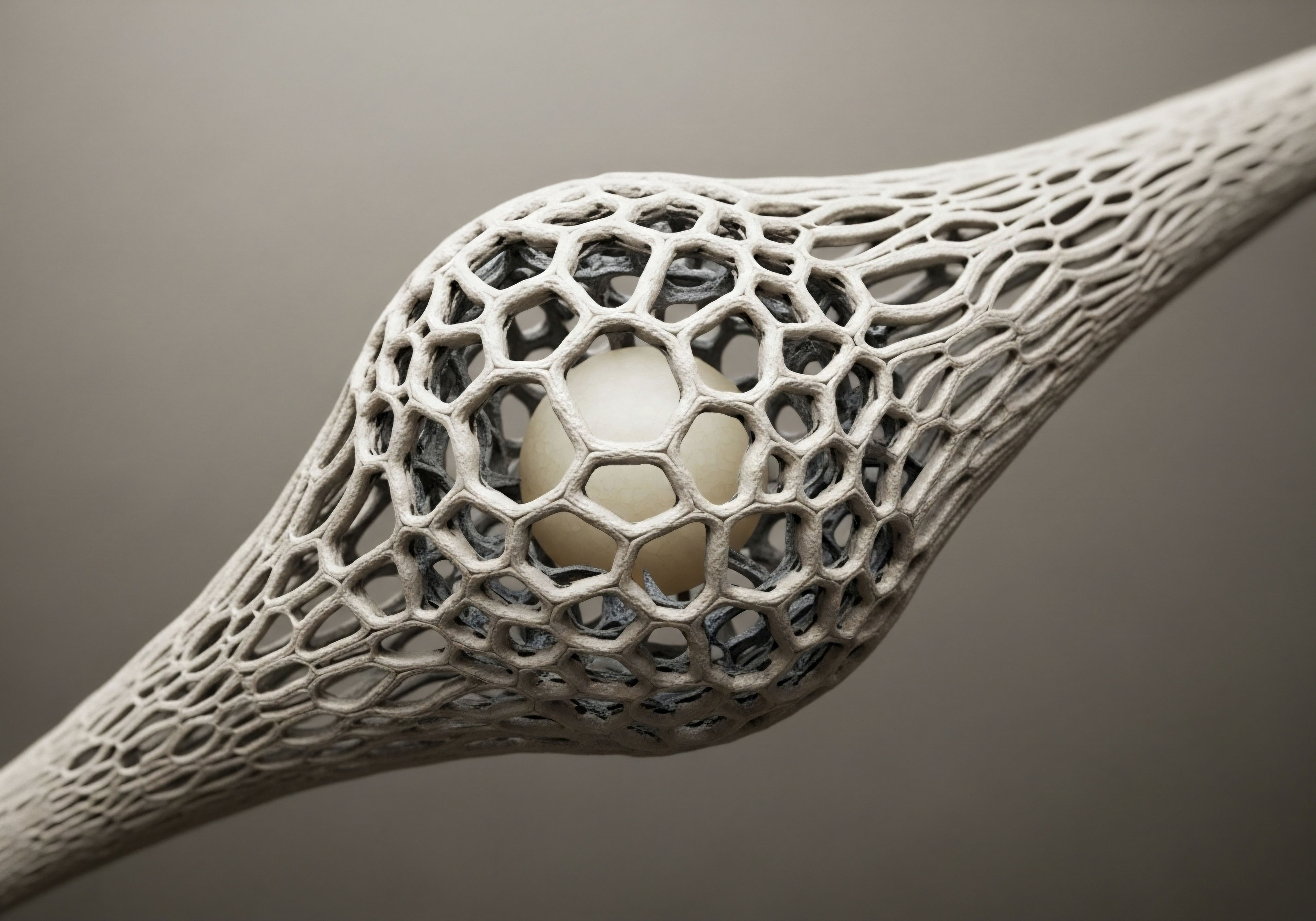

At the center of this response is a sophisticated command and control system known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Think of it as your body’s internal emergency broadcast system.

When your brain perceives a stressor ∞ be it a looming work deadline, an argument, or a severely restrictive diet ∞ the hypothalamus sends a signal to the pituitary gland, which in turn signals the adrenal glands to release a flood of hormones. The most prominent of these is cortisol.

Cortisol is a powerful and necessary hormone. In short bursts, it sharpens your focus, mobilizes energy by increasing blood sugar, and primes your body for action. This is the “fight or flight” response, a brilliant evolutionary adaptation. The system is designed to resolve the threat and then return to a state of calm, or homeostasis.

The wellness programs that promise optimization can, through their rigidity and pressure, create a state of chronic, low-grade stress. This transforms the life-saving, short-term release of cortisol into a sustained, damaging flood. The emergency broadcast system never shuts off. This prolonged activation of the HPA axis is where the journey toward metabolic dysfunction begins.

The body, perceiving a continuous state of emergency, starts making executive decisions to ensure survival. These decisions, while logical from a primitive standpoint, are directly at odds with the goals of fat loss, muscle gain, and overall vitality. The body begins to prioritize immediate energy availability and conservation, setting the stage for weight gain and metabolic issues.

The relentless pursuit of wellness can itself become a chronic stressor, activating the body’s survival mechanisms and paradoxically undermining metabolic health.

The Cortisol Cascade

When cortisol levels are persistently elevated, the hormone’s beneficial effects begin to invert. Its primary role in mobilizing energy becomes a liability. Cortisol stimulates a process called gluconeogenesis in the liver, which is the creation of glucose from sources like amino acids. This action continuously elevates blood sugar levels.

To manage this influx of sugar, the pancreas secretes insulin, the hormone responsible for shuttling glucose into cells for energy. Over time, with both cortisol and glucose chronically high, cells can become less responsive to insulin’s signals. This phenomenon is known as insulin resistance. It is a critical turning point in metabolic health.

When cells are insulin resistant, the body requires more and more insulin to do the same job, leading to high circulating levels of both glucose and insulin, a condition that promotes fat storage, particularly in the abdominal region.

This process creates a vicious cycle. The high insulin levels block fat from being released from fat cells to be burned for energy. Simultaneously, the elevated cortisol directly encourages the body to store fat, especially visceral fat, the metabolically active and dangerous fat that surrounds the internal organs.

This is a survival mechanism; in times of perceived famine (which a restrictive diet mimics), the body hoards energy. The brain, also running on glucose, feels the impact of these fluctuations, leading to cravings for high-sugar, high-fat foods to quickly replenish its perceived energy deficit. This entire cascade is a physiological response to a perceived threat, a threat manufactured by the very wellness program intended to bring health.

Beyond the Scale

The metabolic consequences extend far beyond simple weight gain. The constant demand on the HPA axis can lead to a state of dysregulation, where the natural daily rhythm of cortisol is disrupted. Normally, cortisol is highest in the morning to promote wakefulness and gradually tapers throughout the day.

Chronic stress can flatten this curve, leading to feelings of being “tired but wired,” difficulty falling asleep, and profound morning fatigue. This sleep disruption further exacerbates insulin resistance and hormonal imbalance. The body’s intricate network of systems is interconnected.

A disruption in one, like the HPA axis, inevitably ripples through the others, affecting everything from immune function to cognitive clarity and reproductive health. The pressure of a wellness program, therefore, is not just a mental burden; it is a physical one with measurable metabolic consequences.

Intermediate

To fully grasp how a well-intentioned wellness protocol can instigate metabolic decline, we must move beyond the general concept of stress and examine the specific biochemical conflicts that arise. The body operates on a principle of resource allocation, managed by the endocrine system.

When faced with a perceived chronic threat ∞ such as the combined pressure of caloric restriction, intense exercise, and the psychological demand for perfection ∞ the body enters a state of triage. It prioritizes the production of stress hormones over other vital hormonal pathways. This biological prioritization is a direct contributor to weight gain, fatigue, and the very symptoms individuals are trying to resolve.

This process is often referred to as “pregnenolone steal” or, more accurately, a functional shunting of resources. Pregnenolone is a foundational precursor hormone, a “mother hormone” from which many others, including cortisol and sex hormones like DHEA, testosterone, and progesterone, are synthesized. Under normal conditions, pregnenolone is converted down various pathways as needed to maintain hormonal balance.

When the HPA axis is in a state of sustained alarm, the demand for cortisol becomes relentless. The enzymatic machinery responsible for hormone synthesis is upregulated toward the cortisol production line. Resources that would have been allocated to producing DHEA, testosterone, and progesterone are diverted to meet the demand for cortisol. This creates a functional deficiency in sex hormones, even when the glands themselves are healthy.

Under chronic stress, the body’s hormonal production pathways are rerouted to prioritize cortisol, effectively ‘stealing’ the building blocks from vital sex hormones like testosterone and progesterone.

The Sex Hormone Sacrifice

The consequences of this hormonal shunting are significant and directly impact metabolic function and body composition. Both men and women suffer when their sex hormone balance is compromised by chronically elevated cortisol.

How Does Stress Affect Female Hormones?

In women, progesterone is particularly vulnerable to this resource diversion. Progesterone is crucial for regulating the menstrual cycle, supporting mood, and promoting restful sleep. When its production is downregulated in favor of cortisol, women may experience irregular cycles, increased PMS symptoms, anxiety, and insomnia.

Furthermore, cortisol can directly block progesterone receptors, meaning that even the progesterone that is available cannot effectively do its job. This creates a state of functional estrogen dominance, not because estrogen is necessarily high, but because its ratio to progesterone is skewed. This imbalance can contribute to weight gain, particularly in the hips and thighs, as well as water retention and mood lability.

How Does Stress Affect Male Hormones?

In men, the impact is equally profound. Chronically elevated cortisol sends a suppressive signal to the entire Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. It reduces the release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which in turn reduces the pituitary’s release of Luteinizing Hormone (LH).

LH is the direct signal for the testes to produce testosterone. The result is a centrally mediated suppression of testosterone production. Low testosterone contributes to fatigue, depression, reduced libido, and, critically for metabolic health, a loss of muscle mass and an increase in visceral fat. Since muscle is a primary site for glucose disposal, losing muscle mass further worsens insulin sensitivity, reinforcing the metabolic dysfunction initiated by cortisol.

The table below illustrates the contrasting effects of acute, healthy stress (like a single workout) versus the chronic stress induced by a high-pressure wellness program on key hormones.

| Hormone | Response to Acute Stressor | Response to Chronic Wellness Pressure |

|---|---|---|

| Cortisol |

Sharp, temporary increase; returns to baseline |

Chronically elevated; blunted daily rhythm |

| Testosterone |

Minor, transient fluctuation |

Sustained suppression via HPG axis |

| Progesterone |

Minimal immediate impact |

Decreased production due to pregnenolone shunting |

| Insulin |

Temporary increase to manage glucose mobilization |

Chronically elevated, leading to receptor resistance |

| Ghrelin (Hunger Hormone) |

Often suppressed during the event |

Elevated, driving cravings for energy-dense foods |

The Thyroid Connection

The thyroid gland, the master regulator of metabolism, is also highly sensitive to the chronic stress state. The body’s primary thyroid hormone is Thyroxine (T4), which is relatively inactive. For the body to use it, T4 must be converted into the active form, Triiodothyronine (T3).

This conversion process is inhibited by high levels of cortisol. Therefore, an individual can have perfectly normal lab results for TSH and T4, yet suffer from symptoms of hypothyroidism ∞ such as weight gain, fatigue, cold intolerance, and hair loss ∞ because their body cannot make the final, crucial conversion to the active T3 hormone.

This is another example of the body’s survival intelligence at work; in a state of perceived famine or danger, it slows down the metabolic rate to conserve energy. This adaptive response, when triggered by a wellness program, becomes a significant barrier to progress.

The following list details common symptoms that arise from this interconnected web of HPA axis and HPG axis dysregulation:

- Persistent Abdominal Fat ∞ A direct result of high cortisol and insulin resistance.

- Muscle Loss (Sarcopenia) ∞ Caused by cortisol’s catabolic effects and suppressed testosterone.

- Fatigue and Sleep Disturbances ∞ Stemming from a disrupted cortisol rhythm and low progesterone.

- Increased Cravings ∞ Driven by hormonal signals for quick energy and disrupted appetite regulation.

- Mood Changes ∞ Including anxiety, irritability, and depressive symptoms linked to imbalances in progesterone, testosterone, and cortisol.

- Cognitive Fog ∞ A consequence of blood sugar instability and the neuroinflammatory effects of chronic stress.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the metabolic consequences of high-pressure wellness protocols requires an examination of the cellular and systemic adaptations that constitute allostasis and allostatic load. The concept of allostasis describes the body’s ability to achieve stability through change, a dynamic process of adaptation to stressors.

Allostatic load represents the cumulative cost of this adaptation, the physiological wear and tear that results from chronic overactivity or dysregulation of the allostatic systems. The pressure of a modern wellness program, with its confluence of psychological striving, dietary restriction, and physical exertion, acts as a potent trigger for allostatic overload, driving molecular changes that precipitate metabolic syndrome.

The primary mediator of this process is the glucocorticoid signaling pathway. Chronically elevated cortisol leads to a state of glucocorticoid receptor resistance (GRR) in key tissues, including the hypothalamus and pituitary. This is a protective downregulation of cortisol receptors to shield the cells from the toxic effects of excessive stimulation.

This resistance in the central nervous system impairs the negative feedback loop of the HPA axis. The brain no longer effectively senses the high levels of circulating cortisol, so it fails to send the “shut-off” signal. This creates a feed-forward loop where the perception of stress continues to drive cortisol production, even as peripheral tissues become less sensitive to its signals. This dynamic is a central pathology in metabolic syndrome.

The cumulative physiological burden of chronic stress, termed allostatic load, leads to glucocorticoid receptor resistance, disrupting the HPA axis’s negative feedback and perpetuating a cycle of metabolic dysregulation.

Molecular Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance

At the molecular level, glucocorticoids induce insulin resistance through multiple mechanisms, particularly in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. In skeletal muscle, glucocorticoids interfere with post-receptor insulin signaling. They decrease the transcription and phosphorylation of Insulin Receptor Substrate-1 (IRS-1), a key docking protein in the insulin signaling cascade.

This impairment cripples the cell’s ability to activate the PI3K-Akt pathway, which is essential for stimulating the translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell membrane. With fewer GLUT4 transporters at the surface, glucose uptake from the bloodstream is significantly reduced, contributing to hyperglycemia.

In the liver, cortisol amplifies hepatic glucose production by upregulating the expression of key gluconeogenic enzymes like Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase (PEPCK) and Glucose-6-Phosphatase. Simultaneously, it promotes lipolysis in adipose tissue, releasing free fatty acids (FFAs) into circulation. These FFAs are taken up by the liver and muscle, where they contribute to ectopic fat deposition (e.g.

hepatic steatosis) and further exacerbate insulin resistance through mechanisms of lipotoxicity. The constant exposure to high cortisol and FFAs creates a state of low-grade, sterile inflammation, with increased production of cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6, which are themselves potent antagonists of insulin signaling.

The following table outlines the specific molecular impacts of chronic cortisol elevation on tissues critical to metabolic health.

| Tissue | Molecular Impact of Excess Glucocorticoids | Resulting Pathophysiology |

|---|---|---|

| Skeletal Muscle |

Decreased IRS-1 transcription; impaired PI3K-Akt pathway activation; reduced GLUT4 translocation. |

Impaired glucose uptake; peripheral insulin resistance. |

| Liver |

Upregulation of PEPCK and G6Pase; increased gluconeogenesis; FFA uptake and ectopic fat storage. |

Hepatic insulin resistance; hyperglycemia; non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. |

| Adipose Tissue |

Increased lipolysis; release of FFAs; altered adipokine secretion (decreased adiponectin). |

Systemic lipotoxicity; inflammation; central obesity. |

| Pancreatic β-cells |

Impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion; potential for glucolipotoxicity-induced apoptosis. |

β-cell dysfunction; eventual failure to compensate for insulin resistance. |

The Neurobiology of Orthorexia

The drive for “clean” eating and perfect health, termed Orthorexia Nervosa when it becomes pathological, has a distinct neurobiological signature that perpetuates HPA axis activation. This behavior is often underpinned by activity in the brain’s reward and habit-formation circuits, particularly the dorsal striatum.

The initial positive feedback from achieving a dietary or exercise goal can become a rigid, compulsive behavior. The psychological stress associated with deviating from these self-imposed rules ∞ the fear of consuming “impure” foods or missing a workout ∞ is a powerful activator of the HPA axis. This creates a situation where the very act of maintaining the wellness program is the primary source of chronic stress.

This psychological rigidity is linked to alterations in prefrontal cortex function, the brain region responsible for executive function and cognitive flexibility. Chronic stress is known to impair prefrontal cortex activity, reinforcing rigid thinking and making it more difficult for an individual to adapt their behavior, even in the face of negative consequences like weight gain and fatigue.

The individual becomes trapped in a neurobiological loop where the solution (stricter adherence) becomes the problem itself. This is the ultimate paradox ∞ the cognitive pursuit of health directly creates the physiological conditions for disease.

- Allostatic Load ∞ This represents the cumulative physiological cost of adaptation to chronic stress, a key factor in the development of metabolic diseases.

- Glucocorticoid Receptor Resistance ∞ A state where cells downregulate cortisol receptors to protect against overstimulation, impairing the HPA axis negative feedback loop.

- IRS-1 Downregulation ∞ A specific molecular mechanism by which cortisol blocks insulin signaling within cells, leading to insulin resistance.

- Lipotoxicity ∞ The damaging effect of excess free fatty acid accumulation in non-adipose tissues like the liver and muscle, which further disrupts metabolic function.

References

- Kyrou, Ioannis, and Constantine Tsigos. “Stress hormones ∞ physiological stress and regulation of metabolism.” Current opinion in pharmacology 9.6 (2009) ∞ 787-793.

- Ranabir, Salam, and K. Reetu. “Stress and hormones.” Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism 15.1 (2011) ∞ 18.

- Hewagalamulage, S. D. et al. “Stress, cortisol, and obesity ∞ a role for cortisol responsiveness in identifying individuals prone to obesity.” Domestic animal endocrinology 56 (2016) ∞ S112-S120.

- McEwen, Bruce S. “Stress, adaptation, and disease ∞ Allostasis and allostatic load.” Annals of the New York academy of sciences 840.1 (1998) ∞ 33-44.

- Pasquali, Renato. “The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sex hormones in chronic stress and obesity ∞ a journey from animals to humans.” Stress 15.3 (2012) ∞ 233-247.

- Geiker, N. R. W. et al. “Does stress influence sleep patterns, food intake, weight gain, abdominal obesity and weight loss interventions and vice versa?.” Obesity reviews 19.1 (2018) ∞ 81-97.

- Tomiyama, A. Janet. “Stress and obesity.” Annual review of psychology 70 (2019) ∞ 703-718.

- Chrousos, George P. “Stress and disorders of the stress system.” Nature reviews endocrinology 5.7 (2009) ∞ 374-381.

- Kassi, E. et al. “HPA axis abnormalities and metabolic syndrome.” Endocrine Abstracts, vol. 41, 2016.

- Ferris, Heather A. and C. Ronald Kahn. “New mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance ∞ make no bones about it.” The Journal of clinical investigation 122.11 (2012) ∞ 3854-3857.

Reflection

The journey through the intricate landscape of your body’s hormonal and metabolic systems reveals a profound truth. Your physiology is not a machine to be conquered, but an ecosystem to be understood. The symptoms you experience are not failures of willpower; they are signals from a body intelligently attempting to survive under a perceived state of duress.

The fatigue, the weight gain, the mental fog ∞ these are the logical outcomes of a system pushed into a state of chronic defense by the very methods promising to optimize it.

What does it mean to listen to this biological feedback? It prompts a shift in perspective, moving from a mindset of rigid control to one of responsive attunement. True wellness may be found in the space between relentless striving and passive acceptance.

It involves questioning the external pressures and internal narratives that define health as a state of perfection to be achieved through punishment. Understanding the science of your own stress response is the first step. The next is to translate that knowledge into a personalized protocol that honors your unique physiology, creating a sustainable path toward vitality that is built on self-awareness, not self-criticism.