Fundamentals

Your body is a responsive, dynamic system, an intricate conversation between hormones, metabolism, and your environment. The impulse to understand this personal biology, to map its unique pathways and reclaim a sense of vitality, is a foundational step in a sophisticated health journey.

This same personal system, however, enters a complex legal and ethical space when it intersects with workplace wellness initiatives. These programs, often presented as pathways to better health, introduce a delicate tension between a corporation’s desire to foster a healthy workforce and your fundamental right to the privacy of your own biological information.

At the heart of this intersection are two critical pieces of federal legislation ∞ The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). These laws function as guardians of your physiological autonomy in the workplace.

The ADA protects individuals from discrimination based on disability, ensuring that participation in wellness programs that include medical examinations or inquiries is genuinely voluntary. GINA extends this protection to your genetic data, safeguarding the sensitive information revealed in your family medical history from being used in employment decisions. Together, they form a regulatory framework that acknowledges a profound truth ∞ your health data is uniquely yours, and its disclosure cannot be coerced, even by the most well-intentioned corporate wellness program.

The core issue revolves around whether financial incentives transform a voluntary wellness program into a coercive one, compelling the disclosure of protected health information.

The incentives offered by these programs, whether rewards like premium discounts or penalties like higher contributions, are the central point of contention. A significant financial incentive can create a powerful pressure to participate, blurring the line between a voluntary choice and an economic necessity.

This raises a critical question ∞ when does an incentive become so substantial that it effectively penalizes those who choose to keep their personal health information private? Understanding this dynamic is the first step in navigating the complex landscape of workplace wellness with both personal agency and legal awareness.

Intermediate

To appreciate the nuances of wellness program compliance, one must first understand the operational distinctions between different program types. The legal framework, particularly under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), differentiates wellness programs into two primary categories.

This classification is pivotal because it dictates the level of regulatory scrutiny applied, especially concerning the size and nature of permissible incentives. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which enforces the ADA and GINA, has its own set of rules that must harmonize with HIPAA’s structure, creating a complex, interlocking system of regulations.

Participatory versus Health Contingent Programs

The two main classifications of wellness programs create different compliance obligations for employers. Understanding their structure reveals why incentives are such a delicate issue.

- Participatory Programs These programs reward employees for mere participation, without requiring a specific health outcome. Examples include attending a health seminar, completing a health risk assessment, or joining a gym. Because they do not require individuals to meet a health-related standard, they are generally subject to less stringent regulation.

- Health-Contingent Programs These programs require individuals to satisfy a standard related to a health factor to obtain a reward. They are further divided into two subcategories:

- Activity-Only Programs These require an individual to perform or complete a health-related activity, such as walking a certain amount each day or adhering to an exercise regimen.

- Outcome-Based Programs These require an individual to attain or maintain a specific health outcome, such as achieving a target cholesterol level, blood pressure, or BMI. These are the most heavily regulated programs because they tie financial rewards directly to physiological states that may be difficult or medically inadvisable for some individuals to achieve.

How Do Incentives Complicate Compliance?

The primary legal conflict arises because health-contingent programs often require medical examinations or disability-related inquiries to verify outcomes. The ADA and GINA mandate that such inquiries must be part of a “voluntary” program. For years, regulatory bodies and the courts have debated what level of incentive renders a program involuntary.

A 30% premium discount might be viewed as an encouragement by some, but for a lower-wage worker, it could feel like a coercive penalty for non-participation, compelling them to disclose sensitive information about a disability or genetic predisposition.

Regulatory guidance has been inconsistent, with rules proposed, legally challenged, and withdrawn, leaving employers in a state of uncertainty.

The EEOC’s stance has evolved over time, reflecting this tension. In 2016, the agency issued rules allowing incentives up to 30% of the cost of self-only health coverage. However, a federal court vacated these rules in 2019, arguing the EEOC had not provided sufficient justification that such a high incentive level preserved the voluntary nature of participation.

Subsequent proposals have suggested limiting incentives to a “de minimis” value, such as a water bottle or a modest gift card, for programs that collect medical data, though these rules were also withdrawn. This regulatory flux highlights the deep-seated difficulty in balancing health promotion with the stringent anti-discrimination protections at the core of the ADA and GINA.

| Program Type | Requirement for Reward | Primary Governing Regulation | Incentive Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participatory | Participation (e.g. attend a seminar) | HIPAA (less stringent) | Generally permissible as long as no medical information is collected. |

| Activity-Only Health-Contingent | Action (e.g. complete a walking program) | HIPAA, ADA, GINA | Must offer a reasonable alternative standard for those unable to participate due to a medical condition. |

| Outcome-Based Health-Contingent | Result (e.g. achieve target BMI) | HIPAA, ADA, GINA (most stringent) | Incentive limits are highly contested and subject to changing EEOC guidance. Must offer a reasonable alternative. |

Academic

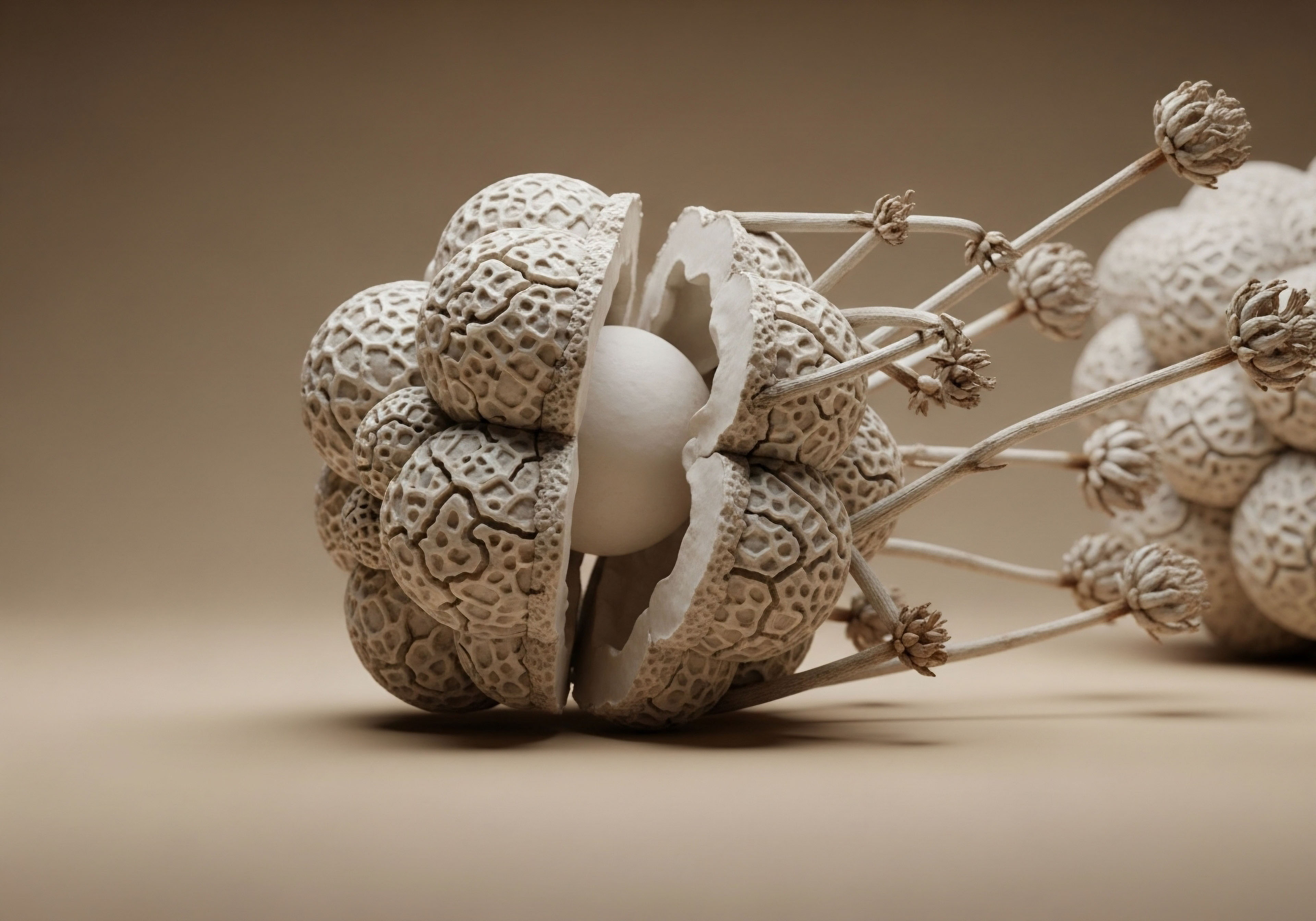

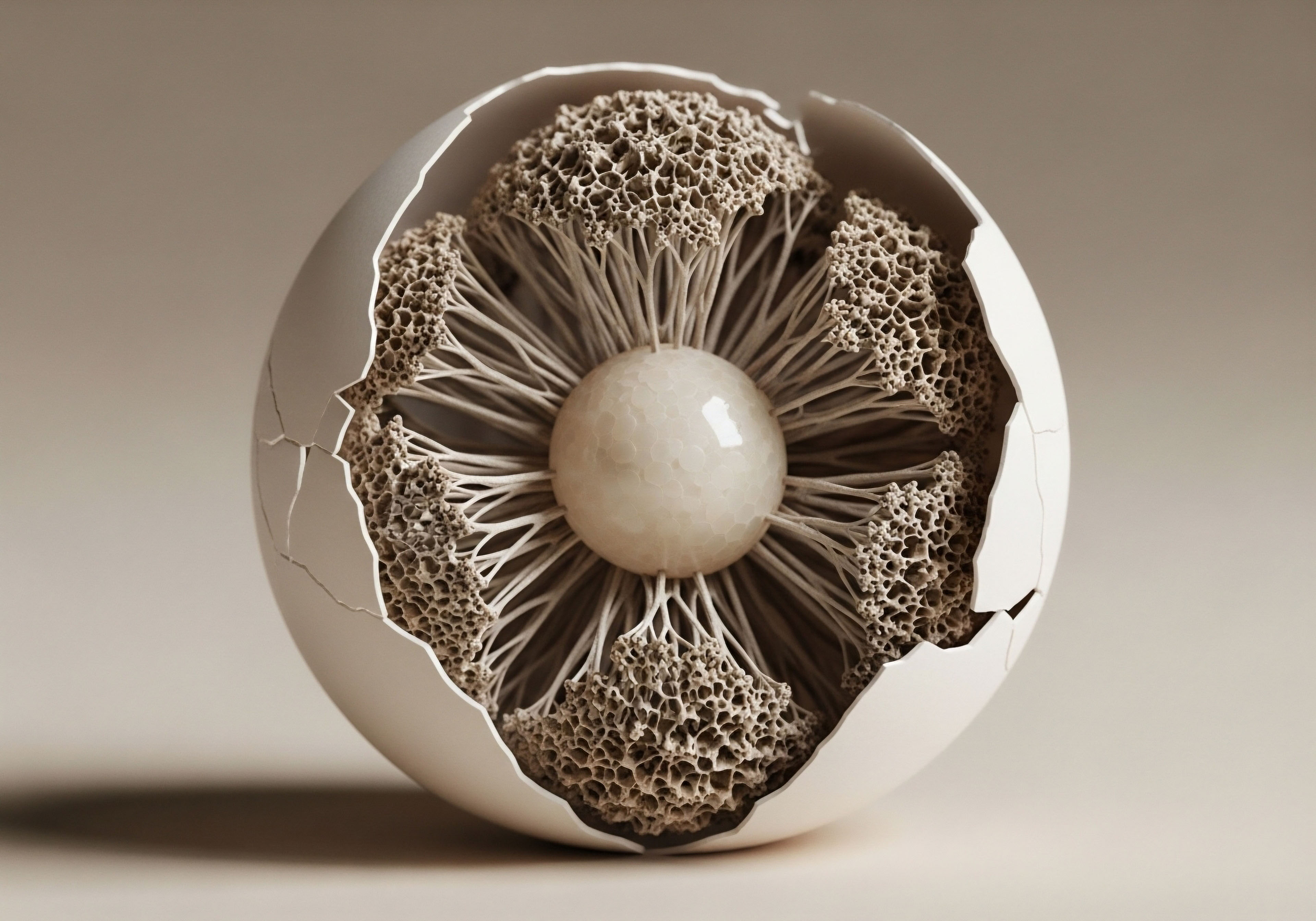

A deeper analysis of wellness program regulation reveals a fundamental conflict between public health utilitarianism and individual rights jurisprudence. From a systems-biology perspective, the human organism is a complex, adaptive system, not a linear equation where a given input reliably produces a desired output.

Health-contingent wellness programs, particularly outcome-based models, often operate on a reductive premise that specific biomarkers can be universally managed through standardized interventions. This approach fails to account for the profound influence of genetics, epigenetic modifications, and the intricate feedback loops of the endocrine system on an individual’s health trajectory.

The Legal Evolution of Voluntariness

The legal interpretation of “voluntary” participation under the ADA and GINA has been a primary battleground. The 2016 EEOC regulations attempted to create a bright-line rule by linking the incentive limit to the 30% cap permitted under HIPAA for health-contingent plans. However, the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, in AARP v.

EEOC (2017), found this justification insufficient. The court reasoned that the EEOC failed to provide a reasoned basis for why a 30% incentive, which could amount to thousands of dollars, did not exert undue economic pressure on employees, thereby rendering participation involuntary and compelling the disclosure of protected health information. This judicial intervention underscores a critical principle ∞ compliance with one statute (HIPAA) does not automatically satisfy the requirements of another (the ADA or GINA).

The legal and ethical frameworks struggle to keep pace with the technological capacity to gather and analyze deeply personal health data.

The subsequent withdrawal of proposed rules in 2021 has created a significant regulatory vacuum, forcing employers to navigate compliance based on the statutes themselves without clear agency guidance. This legal ambiguity is particularly acute in the context of GINA. GINA’s statutory language contains fewer exceptions than the ADA.

For instance, it lacks the ADA’s “safe harbor” provision related to insurance, which has been a source of legal debate. Therefore, offering any incentive in exchange for an employee’s genetic information (including family medical history) is legally perilous, with many legal scholars arguing that only de minimis incentives are permissible under the statute’s strict anti-discrimination mandate.

What Is the Future of Workplace Wellness Regulation?

The future of wellness program regulation will likely be shaped by the increasing sophistication of data collection, including wearable technology and direct-to-consumer genetic testing. As wellness programs seek to integrate this granular data, the potential for discrimination based on predictive health analytics and genetic predispositions grows exponentially.

This elevates the importance of GINA’s protections. Any future regulatory framework must reconcile the potential health benefits of personalized data with the profound ethical and legal imperative to protect individuals from being penalized based on their unique, unchangeable biology. The conversation must shift from broad population-level incentives to a model that respects individual physiological diversity and prioritizes true, uncoerced engagement in health-promoting activities.

| Year | Event | Impact on Wellness Incentives |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Affordable Care Act (ACA) | Amended HIPAA to allow incentives up to 30% of health plan costs for health-contingent programs. |

| 2016 | EEOC Final Rules on ADA and GINA | Attempted to harmonize ADA/GINA with HIPAA by allowing up to a 30% incentive. |

| 2017 | AARP v. EEOC Court Decision | Found the 30% incentive level arbitrary and vacated the incentive portions of the 2016 rules. |

| 2019 | EEOC Rule Vacatur Takes Effect | The 30% safe harbor for incentives under ADA and GINA is officially removed. |

| 2021 | EEOC Proposes and Withdraws New Rules | Proposed limiting incentives to de minimis value, but the rules were withdrawn, creating ongoing uncertainty. |

References

- Brodie, Mollyann, et al. “Americans’ Views On Workplace Wellness Programs.” Health Affairs, vol. 38, no. 3, 2019, pp. 432-439.

- Fowler, E. F. & Barry, C. L. “The Role of Incentives in Workplace Wellness Programs.” Annual Review of Public Health, vol. 41, 2020, pp. 449-463.

- Madison, Kristin M. “The Law and Policy of Workplace Wellness Programs.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, vol. 41, no. 5, 2016, pp. 825-866.

- Schmidt, Harald, et al. “Voluntary or Coercive? The Ethics of Health-Contingent Wellness Incentives.” The Hastings Center Report, vol. 45, no. 3, 2015, pp. 24-34.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.” Federal Register, vol. 81, no. 95, 17 May 2016, pp. 31159-31177.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act.” Federal Register, vol. 81, no. 95, 17 May 2016, pp. 31125-31157.

- Song, H. & Baicker, K. “Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes ∞ A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA, vol. 321, no. 15, 2019, pp. 1491-1501.

Reflection

Your physiological story is written in a language of hormones, genes, and metabolic responses. Learning to read that story is an act of profound self-awareness. The legal frameworks governing wellness programs are not distant abstractions; they are the external rules that determine how you can protect that story’s integrity.

As you continue on your path to understanding your own biological systems, consider how you value the privacy of that information. True wellness is a state of integrated function, and that integration includes the confident assertion of your right to navigate your health journey on your own terms, with your personal data held in your own trust.