Fundamentals

You may feel caught in a physiological crossfire. You begin a protocol to address the challenging symptoms of menopause ∞ the hot flashes, the mood swings, the disruption in sleep ∞ only to find that your thyroid, an entirely different system, seems to have been thrown off balance.

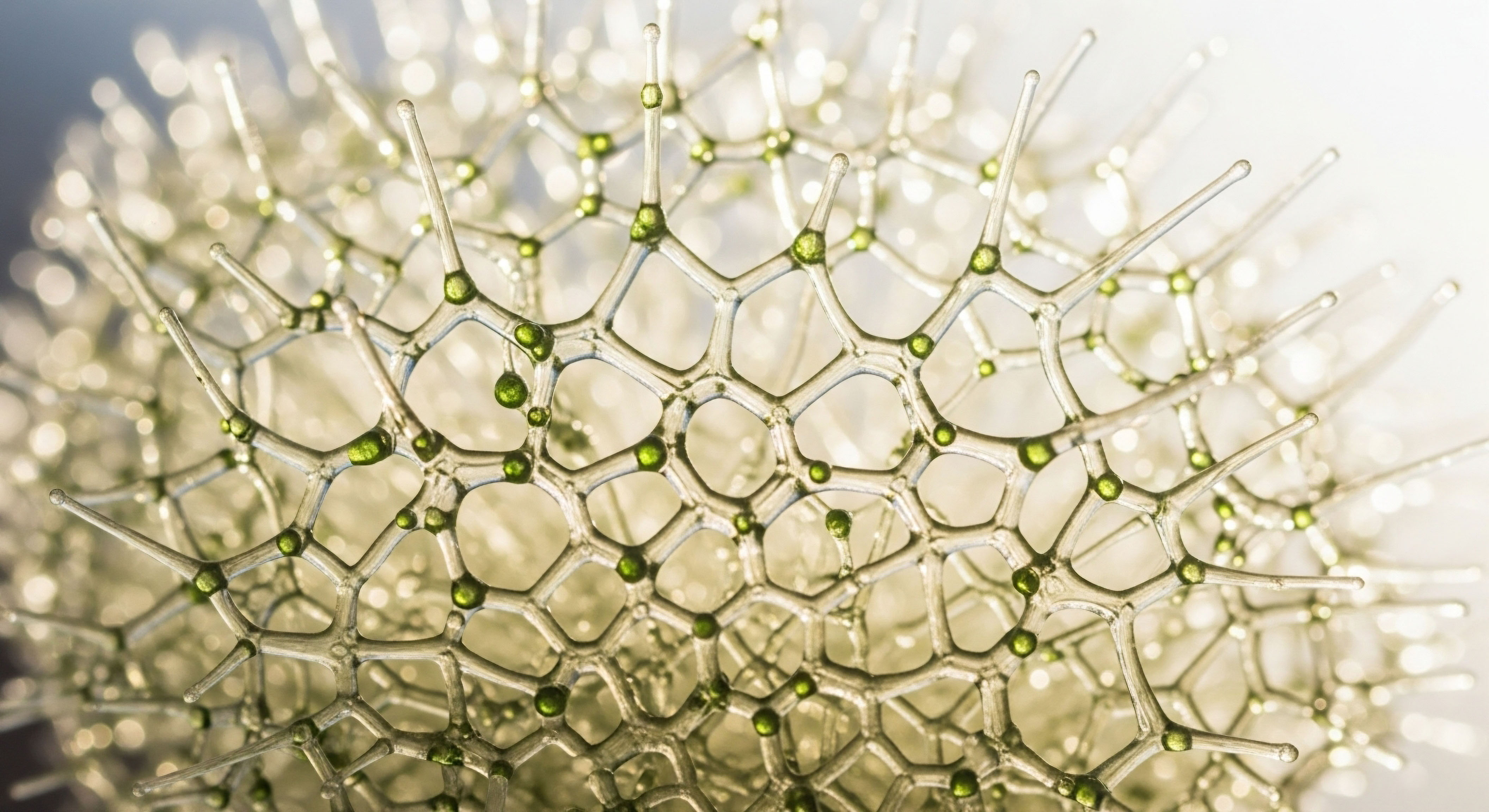

This experience of solving one problem while seemingly creating another is a common and deeply frustrating aspect of managing hormonal health. It speaks to a fundamental truth of our biology ∞ the body is an interconnected system, a seamless web of communication where a single change can send ripples throughout the entire network.

Understanding this interconnectedness is the first step toward reclaiming control. Your endocrine system functions as the body’s internal messaging service. Hormones are the letters, carrying vital instructions from one part of the body to another. Estrogen, produced primarily by the ovaries, and thyroid hormones, produced by the thyroid gland, are two of the most powerful messengers in this network.

They regulate everything from your metabolic rate and body temperature to your mood and cognitive function. For these messages to be delivered and read correctly, the system requires precision and balance.

The method of introducing a hormone into your body directly influences its journey and its ultimate biological effect.

The Journey of a Hormone

When a hormone travels through your bloodstream, it exists in two states ∞ bound and free. Think of Thyroid-Binding Globulin (TBG) as a fleet of transport vehicles for your thyroid hormone (thyroxine, or T4). When T4 is attached to a TBG vehicle, it is “bound” and held in reserve, unable to act on your cells.

When it detaches and travels alone, it is “free” and biologically active, capable of delivering its metabolic instructions. Your body maintains a careful equilibrium between bound and free hormones. The number of available transport vehicles is a critical part of this balance.

This is where the route of administration becomes so important. Any substance you ingest orally, including estrogen pills, must first pass through the liver before it can enter general circulation. This is known as the “first-pass effect.” The liver is a master metabolic organ, and when it processes oral estrogen, it responds by increasing its production of many proteins, including TBG. It essentially builds more transport vehicles.

How Transdermal Delivery Changes the Message

This increase in TBG vehicles means more of your thyroid hormone gets bound up, reducing the amount of free, active T4 available to your cells. Your pituitary gland, the master regulator, senses this drop in active hormone and may signal for an adjustment, which can disrupt your thyroid stability, especially if you are already on thyroid replacement therapy.

Transdermal estrogen, delivered via a patch or gel, follows a different path. It is absorbed directly through the skin into the bloodstream, completely bypassing the first-pass effect in the liver. By avoiding this initial processing, transdermal estrogen does not trigger the liver to produce excess TBG.

The number of transport vehicles remains stable, and the balance of free to bound thyroid hormone is left undisturbed. This route of delivery allows for the targeted benefits of estrogen therapy without creating unintended interference with the thyroid system, offering a more precise and predictable approach to hormonal recalibration.

Intermediate

To truly appreciate the distinction between hormonal delivery systems, we must examine their specific metabolic pathways. The route of administration dictates the biochemical consequences, particularly concerning the liver’s role as a central processing hub for proteins.

When a woman ingests oral estrogen, whether as conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) or micronized estradiol, the hormone is absorbed from the gut and travels directly to the liver through the portal vein. This initial, concentrated exposure stimulates hepatocytes ∞ the primary cells of the liver ∞ to ramp up the synthesis of a wide range of proteins. This includes a significant increase in Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG).

The Clinical Consequences of Hepatic Stimulation

For a woman with a healthy thyroid, the pituitary gland can often compensate for the oral-estrogen-induced drop in free T4 by increasing Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) output, prompting the thyroid to produce more hormone. For a woman on a stable dose of levothyroxine for hypothyroidism, her thyroid gland cannot respond to this increased demand.

The rise in TBG effectively sequesters a larger portion of her medication, leading to a decrease in active hormone levels. This can result in a return of hypothyroid symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, and weight gain. Clinical studies have shown that some women on oral estrogen therapy required an increase in their levothyroxine dosage to maintain a therapeutic balance. This makes the oral route a complicating factor in managing thyroid health.

Transdermal estrogen delivery circumvents the liver’s protein synthesis response, preserving the delicate balance of thyroid hormones.

Transdermal estradiol, delivered through a patch or gel, fundamentally alters this dynamic. By entering the systemic circulation directly through the skin, it bypasses the portal vein and the hepatic first-pass effect. The liver is exposed to a more steady, physiological concentration of estrogen, which does not provoke the same surge in protein production.

As a result, transdermal estrogen administration has been shown to have a minimal effect on TBG levels. This lack of interference means that for a woman on thyroid hormone replacement, her existing dose of levothyroxine remains effective, her free T4 levels stay consistent, and her TSH remains stable. This predictability makes transdermal delivery a superior clinical choice for women requiring both estrogen and thyroid hormone support.

Comparing Delivery Routes a Clinical Overview

The differences between oral and transdermal estrogen are not subtle. They are quantifiable and have direct implications for patient management. The following table illustrates the distinct effects of each route on key endocrine biomarkers.

| Biomarker | Oral Estrogen Effect | Transdermal Estrogen Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG) | Significant Increase (~40%) | Minimal to No Change (~0.4%) |

| Total Thyroxine (T4) | Significant Increase (~28%) | Minimal to No Change (~-0.7%) |

| Free Thyroxine (T4) | Slight Decrease (~-10%) | Minimal to No Change (~0.2%) |

| Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) | Potential for increase, may require dose adjustment in hypothyroid patients | Generally stable, no dose adjustment needed |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) | Marked Increase (~132%) | Slight Increase (~12%) |

This data clarifies why the choice of delivery system is a critical component of a personalized wellness protocol. For women with underlying thyroid conditions, selecting a transdermal route is a strategic decision to ensure the stability of one endocrine system while treating another.

- Baseline Assessment ∞ Before initiating any hormone therapy, a comprehensive thyroid panel, including TSH, free T4, and free T3, is essential to establish a stable baseline.

- Route Selection ∞ For women with known hypothyroidism, especially those on levothyroxine, transdermal estrogen is the clinically preferred first-line option to avoid destabilizing thyroid function.

- Consistent Monitoring ∞ If oral estrogen is chosen for specific clinical reasons, thyroid function should be re-evaluated approximately 6-8 weeks after initiation to determine if a dosage adjustment of thyroid medication is necessary.

- Patient Education ∞ It is vital that the patient understands the interaction. She should be aware that changes in her estrogen protocol, including starting, stopping, or changing the delivery route, may require a corresponding adjustment to her thyroid medication.

Academic

A systems-biology perspective reveals the administration of exogenous hormones as an intervention that reverberates across multiple interconnected endocrine axes. The interaction between estrogen therapy and thyroid function is a classic example of this principle, with the hepatocyte acting as a central node of integration.

The differential impact of oral versus transdermal estrogen is rooted in the pharmacodynamic stimulation of estrogen receptors (ERs), primarily ER-alpha, within the liver. Oral administration delivers a supraphysiological bolus of estrogen to the liver, triggering a pronounced transcriptional response in hepatocytes. This results in the upregulated synthesis and secretion of a host of binding globulins, including Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG), Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), and Corticosteroid-Binding Globulin (CBG).

Hepatic Protein Synthesis as a Central Node in Endocrine Crosstalk

This hepatic response is a dose-dependent and route-dependent phenomenon. Transdermal delivery, by achieving direct systemic absorption, maintains serum estradiol levels within a more physiological range and avoids the high-concentration first-pass exposure to the liver. Consequently, its effect on hepatic protein synthesis is minimal.

A 2007 crossover study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology provided clear quantitative evidence of this divergence. Oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) led to a 39.9% increase in TBG and a 132.1% increase in SHBG. In stark contrast, transdermal estradiol resulted in a negligible 0.4% increase in TBG and a modest 12.0% increase in SHBG. This demonstrates that the route of delivery is a primary determinant of the systemic hormonal milieu.

The selection of a hormonal delivery system is a strategic intervention with predictable, system-wide endocrine consequences.

The clinical ramifications extend across the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axes. The oral-estrogen-induced surge in TBG lowers the free thyroxine (T4) fraction, which can elevate TSH levels and necessitate an increase in levothyroxine dosage for hypothyroid individuals to maintain euthyroidism.

Simultaneously, the dramatic rise in SHBG significantly reduces the bioavailability of androgens by decreasing the free testosterone fraction by over 30%. Transdermal therapy leaves both free T4 and free testosterone levels largely unchanged. This makes transdermal administration a tool of biochemical precision, allowing clinicians to supplement estrogen while preserving the functional status of other hormonal axes.

How Does Delivery Route Influence Clinical Trial Design?

The profound differences between oral and transdermal estrogen delivery have significant implications for the design and interpretation of clinical research in endocrinology. When studying the effects of hormone therapy on outcomes like cardiovascular health, bone density, or cognitive function, the use of oral estrogen introduces a major confounding variable ∞ its potent, independent effects on hepatic protein synthesis.

For instance, the increase in clotting factors and inflammatory markers seen with oral estrogen is a direct result of the first-pass effect. Therefore, a clinical trial aiming to isolate the specific effects of estradiol on vascular tissue would preferentially use a transdermal route to minimize these confounding hepatic signals. This ensures that the observed outcomes are more likely attributable to the direct action of the hormone on the target tissues rather than a secondary effect of altered liver metabolism.

Comparative Impact on Endocrine Transport Proteins

The following table provides a granular view of the percentage changes from baseline for key binding globulins and their associated hormones, highlighting the divergent paths of oral and transdermal therapies based on clinical trial data.

| Hormone or Protein | Mean % Change with Oral CEE | Mean % Change with Transdermal E2 |

|---|---|---|

| Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG) | +39.9% | +0.4% |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) | +132.1% | +12.0% |

| Cortisol-Binding Globulin (CBG) | +18.0% | -2.2% |

| Free Testosterone | -32.7% | +1.0% |

| Free Thyroxine (T4) | -10.4% | +0.2% |

This evidence underscores a critical principle for both clinical practice and academic research. The choice of a delivery system is not a matter of convenience; it is a fundamental variable that determines the physiological impact of the therapy. For women on thyroid hormone replacement, the use of transdermal estrogen is not merely a preference but a clinical necessity for maintaining homeostatic control and avoiding iatrogenic disruption of the HPT axis.

References

- Mazer, Norman A. “Interaction of estrogen therapy and thyroid hormone replacement in postmenopausal women.” Thyroid, vol. 14, suppl. 1, 2004, pp. S27-34.

- Speroff, Leon, et al. “A randomized, open-label, crossover study comparing the effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen therapy on serum androgens, thyroid hormones, and adrenal hormones in naturally menopausal women.” Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 110, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1-8.

- Camacho, Pauline M. et al. “American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis – 2020 Update.” Endocrine Practice, vol. 26, suppl. 1, 2020, pp. 1-46.

- Barbesino, Giuseppe. “Effects of oral versus transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone on thyroid hormones, hepatic proteins, lipids, and quality of life in menopausal women with hypothyroidism ∞ a clinical trial.” Menopause, vol. 28, no. 9, 2021, pp. 1044-1052.

- Garber, Jeffrey R. et al. “Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults ∞ cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association.” Endocrine Practice, vol. 18, no. 6, 2012, pp. 988-1028.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map of the intricate biological pathways that govern your well-being. It details the precise mechanisms that explain why one therapeutic choice can maintain systemic harmony while another can create disruption. This knowledge is more than academic; it is a tool for advocacy in your own health journey.

Understanding the ‘why’ behind a clinical recommendation transforms you from a passive recipient of care into an active participant. Your body is a unique and complex system, and its symptoms are signals containing valuable information. As you move forward, consider how this deeper insight into your own physiology can inform the conversations you have and the choices you make.

The goal is a partnership with your biology, a calibrated approach that seeks to restore function and vitality with precision and intelligence.