Fundamentals

The feeling of being at odds with your own body can be a deeply unsettling experience. When vitality wanes and personal goals like starting a family feel distant, the search for answers often begins. You may have undergone countless tests, yet the underlying cause of infertility remains elusive.

The investigation into male reproductive health frequently centers on testosterone levels and sperm analysis, while a central metabolic regulator, the thyroid gland, is sometimes left in the shadows. Its influence, however, extends into every cell, governing the pace of life itself. Understanding its role is a primary step in recalibrating your internal biological systems.

Your body operates as a fully integrated system, where each gland and hormone communicates in a constant, flowing dialogue. The thyroid gland, located at the base of your neck, functions as the master controller of your metabolism. It produces two primary hormones, thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which dictate the rate at which your cells convert fuel into energy.

This process is fundamental to everything from your heart rate and body temperature to your cognitive function and, critically, the intricate biological manufacturing required for healthy sperm production. The production of these hormones is itself regulated by Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) from the pituitary gland, creating a feedback loop known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis.

A properly functioning thyroid gland provides the essential metabolic energy required for every biological process, including fertility.

The Thyroid and Testicular Function Connection

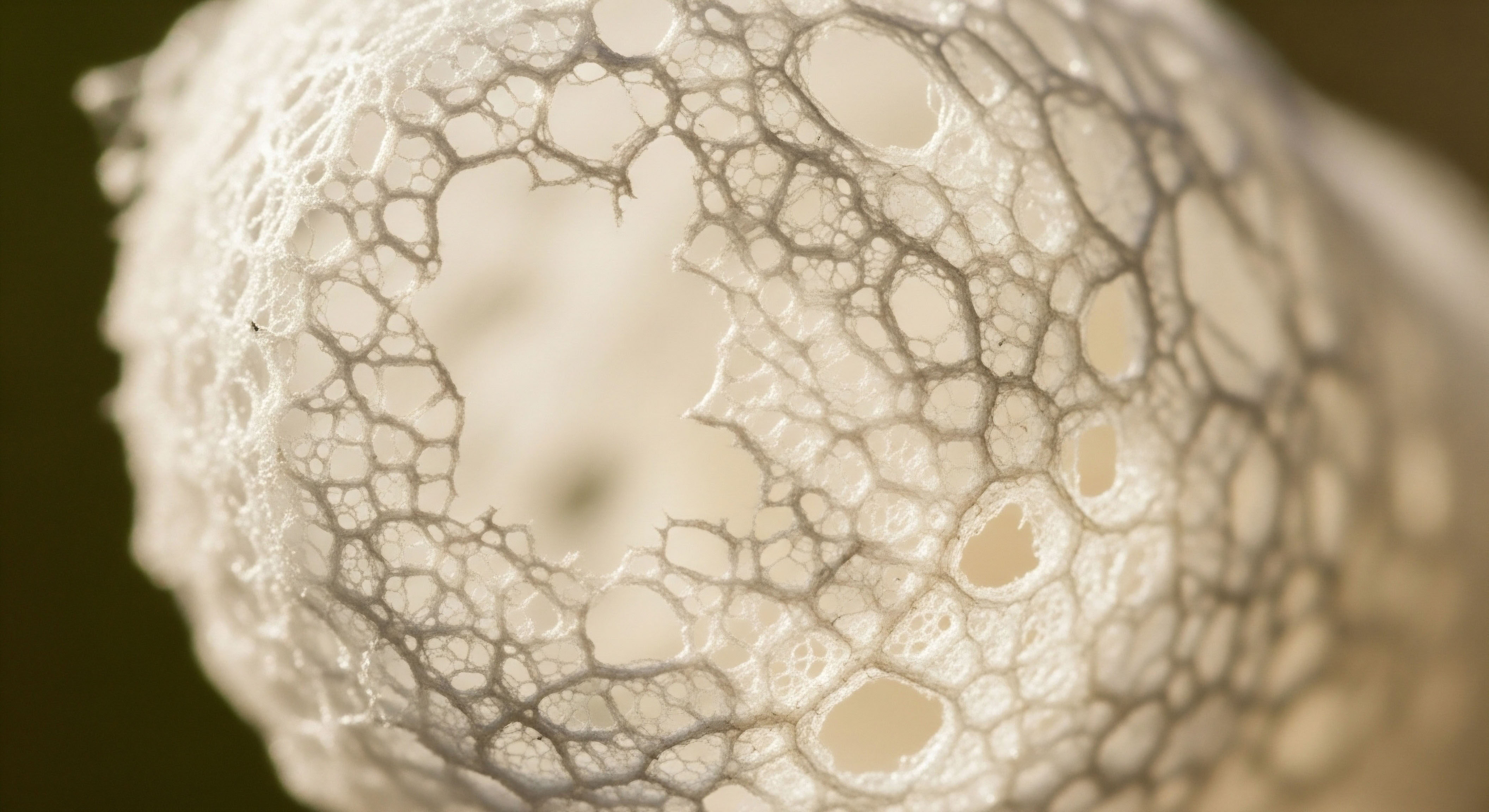

The testes are a site of immense metabolic activity. The creation of sperm, or spermatogenesis, is one of the most complex and energy-demanding processes in the male body. It requires a constant and reliable supply of energy to fuel cell division, maturation, and motility. Thyroid hormones directly influence this environment.

They act on the primary cells within the testes, the Sertoli cells and Leydig cells, to ensure this production line runs efficiently. Sertoli cells are responsible for nurturing developing sperm, while Leydig cells produce testosterone, the principal male sex hormone. An imbalance in thyroid hormones disrupts the function of both cell types, compromising the entire system.

When the thyroid is underactive (hypothyroidism), the body’s metabolic rate slows down. This systemic deceleration affects the testes profoundly, leading to reduced testosterone production and impaired sperm development. Conversely, an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) sends the body into a state of metabolic overdrive.

This acceleration can create a toxic internal environment characterized by oxidative stress, which damages developing sperm cells and impairs their function. Both conditions create a suboptimal environment for fertility, demonstrating that healthy reproductive capacity depends on a precise metabolic balance.

What Are the Initial Signs of Thyroid Imbalance?

Recognizing the symptoms of thyroid dysfunction is the first move toward addressing its impact on fertility. Because thyroid hormones regulate metabolism throughout the body, the signs can be widespread and are often attributed to other causes like stress or aging. A comprehensive view of your symptoms provides valuable information for a clinical evaluation.

- Symptoms of Hypothyroidism (Underactive Thyroid) ∞ This condition reflects a systemic slowing of biological processes. Individuals may experience persistent fatigue, weight gain despite no change in diet, cold intolerance, constipation, dry skin, hair loss, and a depressed mood. In the context of fertility, this can manifest as low libido and erectile dysfunction.

- Symptoms of Hyperthyroidism (Overactive Thyroid) ∞ This condition represents an acceleration of metabolic functions. Common signs include unexplained weight loss, a rapid or irregular heartbeat, anxiety, irritability, tremors, increased sensitivity to heat, and frequent bowel movements. The impact on fertility can be just as significant, though the mechanisms are different.

Acknowledging these symptoms is a validation of your experience. They are tangible signals that your body’s internal communication system requires attention. Addressing the thyroid imbalance with appropriate treatment can, in many cases, alleviate these systemic issues and, in doing so, restore the foundational conditions necessary for male fertility. The path to restoration begins with understanding the root of the disruption.

Intermediate

To appreciate why thyroid treatment is a powerful lever in restoring male fertility, we must examine the intricate communication network that governs male reproductive health. This network involves two primary signaling pathways ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

These are not separate systems; they are deeply interconnected, with the thyroid acting as a key modulator of gonadal function. The HPG axis is the command-and-control pathway for reproduction. It begins with the hypothalamus releasing Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary to secrete Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

LH acts on the Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone, while FSH acts on Sertoli cells to support spermatogenesis. Thyroid hormones influence every step of this cascade.

How Does the Thyroid Influence the HPG Axis?

Thyroid hormones exert their influence through several mechanisms, both direct and indirect. They can modulate the pulsatile release of GnRH from the hypothalamus, which sets the entire rhythm for the HPG axis. An imbalance can alter the frequency and amplitude of these pulses, leading to dysregulated LH and FSH secretion.

This disruption has direct consequences for testicular function, affecting both testosterone synthesis and the sperm maturation process. The result is a hormonal environment that is out of sync, hindering the complex, timed sequence of events required for fertility.

Furthermore, thyroid hormones have a direct impact at the testicular level. Both Sertoli cells and Leydig cells possess receptors for thyroid hormones, allowing T3 to act directly on them. In Leydig cells, thyroid hormones are involved in the process of steroidogenesis, the metabolic pathway that synthesizes testosterone.

In Sertoli cells, they are critical for creating the proper structural and nutritional environment for developing sperm. A deficiency or excess of thyroid hormone directly impairs the function of these foundational cells, leading to problems with sperm count, motility, and morphology.

The crosstalk between the thyroid and gonadal axes means that a disruption in one system inevitably affects the other.

Clinical Manifestations of Thyroid Dysfunction on Male Fertility

The clinical impact of an imbalanced thyroid on male fertility is observable through standard semen analysis and hormonal lab panels. Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism create distinct, yet equally problematic, alterations in reproductive parameters. Correcting the underlying thyroid condition is often the key to normalizing these markers.

| Parameter | Hypothyroidism (Underactive) | Hyperthyroidism (Overactive) |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm Count (Concentration) | Often reduced due to impaired Sertoli cell function and decreased spermatogenesis. | Can be reduced, as the accelerated metabolic state may impair sperm production. |

| Sperm Motility | Significantly decreased progressive motility, linked to reduced energy production within sperm. | Decreased motility, often due to oxidative stress damaging the sperm’s mitochondria and structure. |

| Sperm Morphology | Increased percentage of abnormally shaped sperm, reflecting disruptions in development. | Increased percentage of abnormal forms, potentially due to damage during maturation. |

| Testosterone Levels | May be low or in the low-normal range due to impaired Leydig cell function. | Total testosterone may be elevated, but Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) is also high, reducing free, bioavailable testosterone. |

| Libido and Sexual Function | Commonly associated with low libido, erectile dysfunction, and ejaculatory issues. | Can be associated with erectile dysfunction, though the mechanism is different and may involve altered neurotransmitter function. |

The Path to Restoration through Treatment

When a thyroid imbalance is identified as a contributing factor to infertility, the treatment protocol is aimed at restoring a euthyroid state, meaning a state of normal thyroid function. For hypothyroidism, the standard protocol involves thyroid hormone replacement therapy, typically with levothyroxine (a synthetic form of T4).

The dosage is carefully calibrated based on TSH and T4 levels to bring the HPT axis back into balance. For hyperthyroidism, treatments may include antithyroid medications that reduce hormone production, or in some cases, radioactive iodine therapy. The goal is to stabilize the metabolic rate, which in turn allows the HPG axis to normalize.

In many men, restoring euthyroidism is sufficient to see a significant improvement in semen parameters and overall fertility within several months, as the testicular environment is restored and new, healthy cycles of spermatogenesis complete.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the thyroid’s role in male fertility requires moving beyond systemic hormonal balance to the molecular level of gene expression and cellular bioenergetics within the testicular microenvironment. The answer to whether thyroid treatment alone can restore fertility lies in the reversibility of the cellular changes induced by dysthyroidism.

Thyroid hormones exert their influence by binding to specific nuclear receptors, primarily Thyroid Hormone Receptor alpha (TRα) and Thyroid Hormone Receptor beta (TRβ), which are products of the c-erbA proto-oncogenes. These receptors function as ligand-dependent transcription factors, directly altering the expression of genes critical for testicular function. The presence and differential expression of these receptors in Leydig, Sertoli, and even germ cells provide a direct mechanism for thyroidal regulation of male reproduction.

Genomic and Non Genomic Actions in the Testis

The primary action of T3 is genomic. After entering the cell, T4 is converted to the more active T3, which then translocates to the nucleus and binds to its receptor. The T3-TR complex then binds to Thyroid Hormone Response Elements (TREs) on the promoter regions of target genes, thereby upregulating or downregulating their transcription.

Research has demonstrated that genes responsible for Sertoli cell structural integrity, such as those coding for cytoskeletal proteins like vimentin, are regulated by thyroid hormones. In hypothyroid states, altered phosphorylation of vimentin can compromise the Sertoli cell cytoskeleton, disrupting the physical support essential for developing spermatids and leading to poor morphology.

Furthermore, there is evidence of crosstalk at the genomic level with the androgen axis. The promoter region of the Androgen Receptor (AR) gene itself may be influenced by thyroid hormones, meaning thyroid status can affect the testis’s sensitivity to testosterone.

This creates a multi-layered regulatory system where thyroid hormones not only influence the production of testosterone but also modulate the machinery needed to respond to it. Restoring euthyroidism can normalize the expression of these critical genes, repairing the cellular architecture and function over time.

Thyroid hormones act as powerful genetic switches within testicular cells, directly controlling the machinery of sperm production.

Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Oxidative Stress

Sperm motility is fundamentally a function of energy availability, with the sperm’s midpiece packed with mitochondria to produce the vast amounts of ATP required for flagellar movement. Thyroid hormones are master regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis and function. They stimulate cellular oxygen consumption and the activity of key enzymes in the electron transport chain.

In a hypothyroid state, mitochondrial function is downregulated, leading to insufficient ATP production. This bioenergetic deficit is a direct cause of asthenozoospermia (poor motility), a common finding in infertile men with low thyroid function. Treatment with levothyroxine can restore mitochondrial efficiency and, consequently, sperm motility.

In hyperthyroidism, the situation is different. The metabolic rate is pathologically accelerated, leading to a massive increase in oxygen consumption and electron transport chain activity. A byproduct of this hyperactivity is the excessive production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). When ROS production overwhelms the testis’s endogenous antioxidant defenses, a state of oxidative stress ensues.

This oxidative stress damages mitochondrial DNA, peroxidizes lipids in the sperm’s cell membrane, and fragments sperm DNA, all of which severely compromise sperm viability and function. Therefore, while the hormonal picture may appear different, both hypo- and hyperthyroidism converge on a final common pathway of cellular damage that impairs fertility.

| Cellular Target | Molecular Mechanism | Functional Consequence in Dysthyroidism |

|---|---|---|

| Sertoli Cells | Binds to TRα receptors; regulates transcription of cytoskeletal proteins (e.g. vimentin) and growth factors. | Loss of structural integrity, impaired blood-testis barrier, and inadequate support for spermatogenesis. |

| Leydig Cells | Binds to TRα receptors; modulates expression of steroidogenic enzymes (e.g. StAR protein). | Altered testosterone biosynthesis, leading to hormonal imbalance within the HPG axis. |

| Sperm Mitochondria | Regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and expression of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) enzymes. | Hypothyroidism ∞ Reduced ATP production, causing low motility. Hyperthyroidism ∞ Excessive ROS production, causing oxidative damage. |

| Hypothalamus | Modulates the pulsatility of GnRH secretion through central mechanisms. | Disrupted LH/FSH signaling cascade, affecting the entire HPG axis rhythm. |

When Is Thyroid Treatment Insufficient?

While restoring euthyroidism is a necessary and powerful intervention, it may not be sufficient in all cases. The potential for full recovery depends on the duration and severity of the thyroid dysfunction and the presence of other underlying pathologies.

If chronic thyroid disease has led to irreversible testicular damage, such as significant fibrosis or a permanent depletion of the germ cell population, then simply normalizing thyroid hormone levels will not restore function. Similarly, if the infertility is multifactorial, with coexisting issues like a varicocele, genetic abnormalities, or obstructive azoospermia, then thyroid treatment will only address one piece of the puzzle.

This is why a comprehensive diagnostic workup is so important. Thyroid treatment restores the permissive environment for fertility; it cannot rebuild structures that have been permanently lost or overcome independent barriers to conception. A successful outcome relies on the integrity of the underlying testicular architecture and the absence of other significant confounding factors.

- Permanent Structural Damage ∞ Long-term, severe hypothyroidism can potentially lead to lasting changes in testicular tissue that may not fully resolve with treatment.

- Coexisting Infertility Factors ∞ The presence of other conditions, such as anatomical blockages or primary testicular failure, will require separate interventions.

- Autoimmunity ∞ In cases where the thyroid disorder is autoimmune (e.g. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis), there may be a broader autoimmune state affecting reproductive tissues, which presents additional challenges.

References

- La Vignera, Sandro, et al. “Thyroid-andrology connection ∞ a narrative review.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 9.10 (2020) ∞ 3323.

- Meeker, John D. and Kelly K. Ferguson. “Thyroid hormone action in the male reproductive system.” Journal of endocrinology 222.2 (2014) ∞ R1-R15.

- Kalyani, R. S. K. Singh, and R. K. Sharma. “Thyroid and male reproduction.” Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism 18.1 (2014) ∞ 23.

- Wagner, M. S. D. S. Wajner, and A. L. Maia. “The role of thyroid hormone in testicular development and function.” Journal of endocrinology 199.3 (2008) ∞ 351-365.

- Bhasin, Shalender, et al. “Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 103.5 (2018) ∞ 1715-1744.

- Garolla, Andrea, et al. “Thyroid and male fertility.” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 18.1 (2020) ∞ 1-11.

- Trummer, H. and H. P. Breinl. “Thyroid hormones and male fertility.” Der Urologe. Ausg. A 41.3 (2002) ∞ 243-247.

- Aitken, R. John. “Oxidative stress and the etiology of male infertility.” The Journal of clinical endocrinology & metabolism 106.3 (2021) ∞ e1229-e1245.

Reflection

Integrating the Knowledge into Your Personal Health

The information presented here provides a detailed map of the biological connections between your thyroid and your reproductive health. This knowledge serves a distinct purpose ∞ to shift your perspective from one of passive concern to one of active, informed participation in your own wellness journey.

Your body is a coherent system, and the symptoms you experience are its language. Understanding the science behind this language is the first step toward deciphering its messages and taking targeted action. The question of fertility is rarely about a single, isolated variable. It is about the harmony of the entire system.

Consider where the imbalances in your own life ∞ be they metabolic, nutritional, or stress-related ∞ might be contributing to the larger picture. This journey of biological understanding is deeply personal, and the path forward involves seeing your health not as a series of disconnected problems, but as a single, integrated whole that you have the power to recalibrate.

Glossary

thyroid hormones

spermatogenesis

sertoli cells

leydig cells

hyperthyroidism

hypothyroidism

oxidative stress

male fertility

hpg axis

thyroid hormones exert their influence

testosterone synthesis

thyroid hormone

semen analysis

hpt axis

hormones exert their influence