Fundamentals

The experience of shifting moods during perimenopause is a deeply personal and often disorienting one. You may feel as though your internal emotional landscape is changing without your consent, leading to a sense of disconnect from the person you’ve always known yourself to be.

This is a valid and widely shared experience, rooted in the profound biological recalibration occurring within your body. The fluctuating hormonal symphony that has governed your cycles for decades begins to play a new, sometimes erratic, tune. Understanding this process is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of control and well-being.

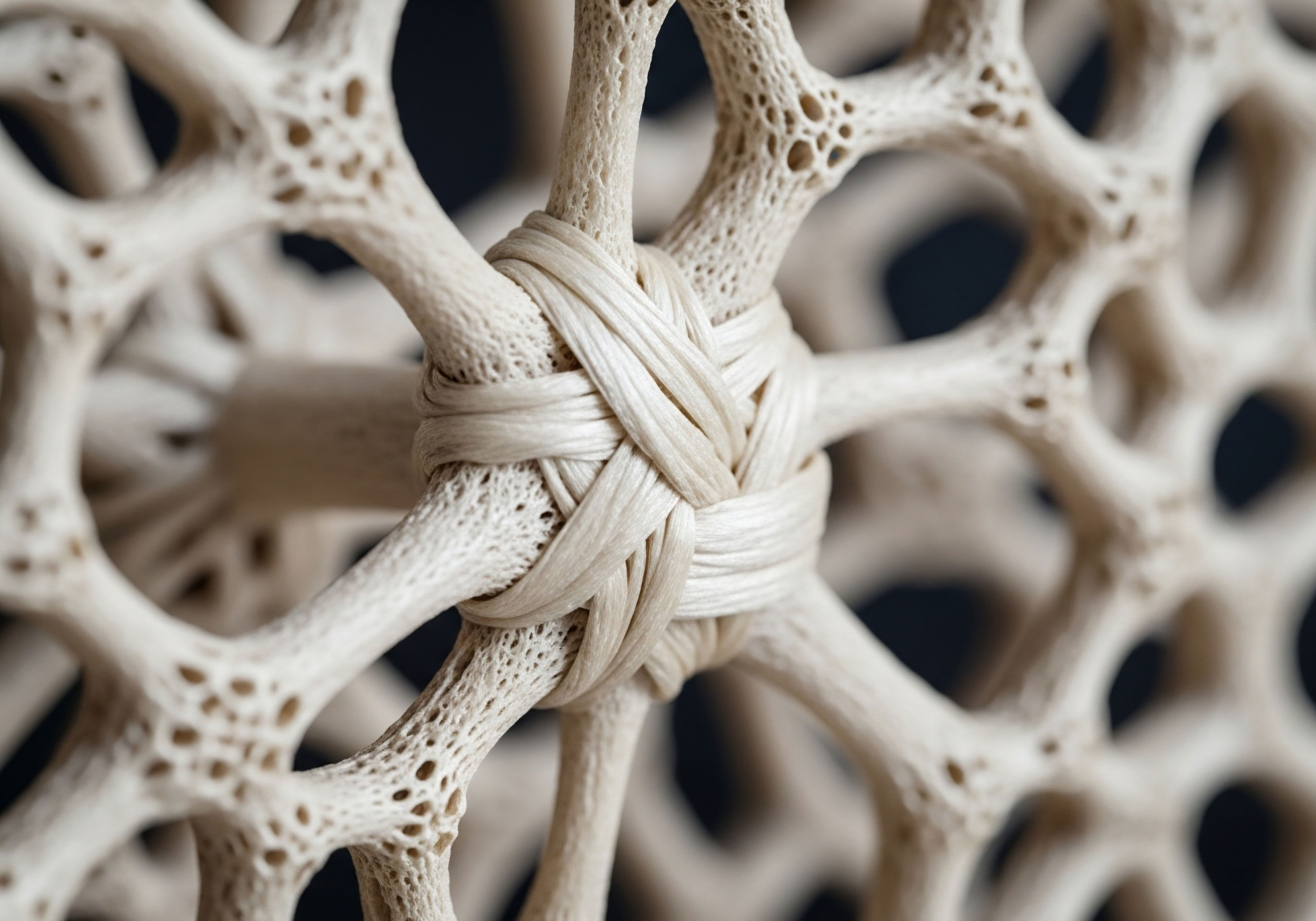

The primary architects of this change are the sex hormones estrogen and progesterone. These molecules are far more than reproductive messengers; they are potent regulators of brain chemistry. Estrogen, for instance, directly influences the production and activity of serotonin and dopamine, neurotransmitters that are fundamental to mood stability, focus, and feelings of pleasure.

When estrogen levels fluctuate unpredictably during perimenopause, dropping and surging, the steadying influence on these neurochemicals is disrupted. This can manifest as increased irritability, sudden sadness, or a pervasive sense of anxiety that seems to arise from nowhere.

Simultaneously, progesterone levels are also declining. Progesterone supports the activity of GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), the brain’s primary calming neurotransmitter. It acts as a natural brake on the nervous system, promoting relaxation and restful sleep. As progesterone wanes, this calming influence diminishes, leaving the nervous system more susceptible to stress and agitation.

The result is a brain that is biochemically predisposed to heightened emotional reactivity. The symptoms you feel are a direct reflection of these neurological shifts. They are not a failure of will or character; they are a physiological response to a changing internal environment.

The emotional volatility experienced during perimenopause is a direct neurological consequence of fluctuating hormones that regulate key mood-stabilizing neurotransmitters.

This transition impacts more than just mood. The same hormonal fluctuations are responsible for a cascade of other symptoms that are often interconnected. Hot flashes and night sweats, for example, originate in the hypothalamus, the brain’s thermostat, which is highly sensitive to estrogen levels.

When this region is dysregulated, it can trigger sudden feelings of intense heat, disrupting comfort and, most critically, sleep. Chronic sleep deprivation, in turn, severely impairs the brain’s ability to manage stress and regulate emotion, creating a feedback loop where physical symptoms exacerbate emotional distress. Recognizing this interconnectedness is key. The mood swings are not happening in isolation; they are part of a systemic shift that affects sleep, temperature regulation, and cognitive function.

Intermediate

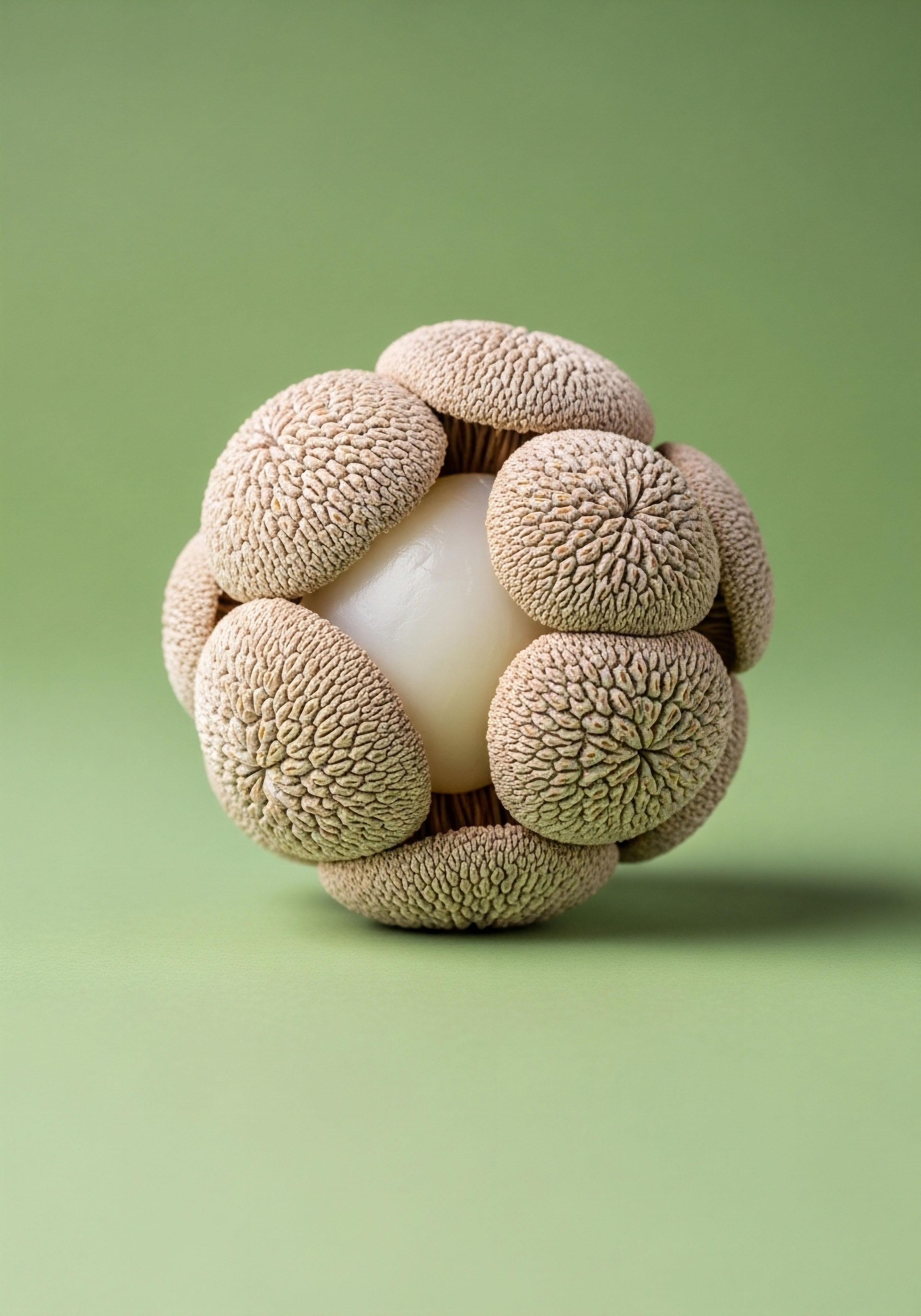

To effectively address perimenopausal mood symptoms, it is beneficial to move beyond simple symptom management and engage with the underlying neuro-hormonal mechanisms. Lifestyle interventions, when applied with precision and consistency, can act as powerful modulators of this internal environment.

They function not as mere distractions, but as targeted inputs that help stabilize the very systems that hormonal fluctuations disrupt. These interventions can be understood as a form of biological communication, providing the body with the resources it needs to find a new equilibrium.

Can Strategic Nutrition Rebalance Brain Chemistry?

The food you consume provides the raw materials for neurotransmitter synthesis and hormonal balance. A diet rich in phytoestrogens ∞ plant-based compounds that can weakly bind to estrogen receptors ∞ may help buffer the effects of fluctuating estrogen levels. Sources like flaxseeds, chickpeas, and lentils can provide a gentle, stabilizing influence.

Moreover, the amino acid tryptophan, found in foods like turkey, nuts, and seeds, is a direct precursor to serotonin. Ensuring an adequate intake of tryptophan, alongside B vitamins which act as essential cofactors in its conversion, can support the brain’s capacity to produce this crucial mood-regulating neurotransmitter. Omega-3 fatty acids, abundant in fatty fish, are integral to brain cell membrane health, facilitating better communication between neurons and exhibiting anti-inflammatory properties that can protect neurological function.

Exercise as a Neurotransmitter Modulator

Physical activity is a potent intervention for recalibrating brain chemistry. Aerobic exercise has been shown to increase levels of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, effectively acting as a natural antidepressant. It also boosts the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports the survival of existing neurons and encourages the growth of new ones.

This process, known as neurogenesis, is vital for cognitive resilience and emotional regulation. Resistance training, in turn, improves insulin sensitivity. This is particularly important during perimenopause, as hormonal shifts can lead to insulin resistance, a condition that is itself linked to mood disturbances and cognitive fog. By improving how the body handles glucose, strength training helps to prevent the energy crashes and inflammation that can negatively impact mood.

Consistent, targeted exercise protocols can directly modulate neurotransmitter levels and enhance neuroplasticity, counteracting the neurological disruption caused by hormonal shifts.

The following table outlines how specific lifestyle interventions can target other common perimenopausal symptoms, illustrating the interconnected nature of these physiological changes.

| Symptom | Lifestyle Intervention | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Hot Flashes / Night Sweats | Consistent Exercise | Improves thermoregulation by enhancing hypothalamic function and reducing core body temperature over time. |

| Sleep Disruption | Mindfulness & Meditation | Lowers cortisol levels and activates the parasympathetic nervous system, making it easier to fall asleep and stay asleep. |

| Cognitive Fog | Complex Carbohydrates & Omega-3s | Provides a steady supply of glucose for brain energy and essential fatty acids for optimal neuronal membrane function. |

| Vaginal Dryness | Hydration & Phytoestrogens | Supports mucosal tissue health system-wide, while phytoestrogens may provide mild estrogenic support to tissues. |

The Role of Stress and the HPA Axis

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system, becomes particularly sensitive during perimenopause. Chronic stress leads to elevated cortisol levels, which can further disrupt sleep, impair memory, and contribute to depressive symptoms. Practices like yoga, deep breathing, and meditation are not just for relaxation; they are powerful tools for down-regulating the HPA axis.

By consciously activating the parasympathetic “rest and digest” nervous system, these practices can lower cortisol, increase GABA activity, and build greater resilience to stress, preventing the adrenal system from amplifying the mood swings initiated by ovarian hormone decline.

Academic

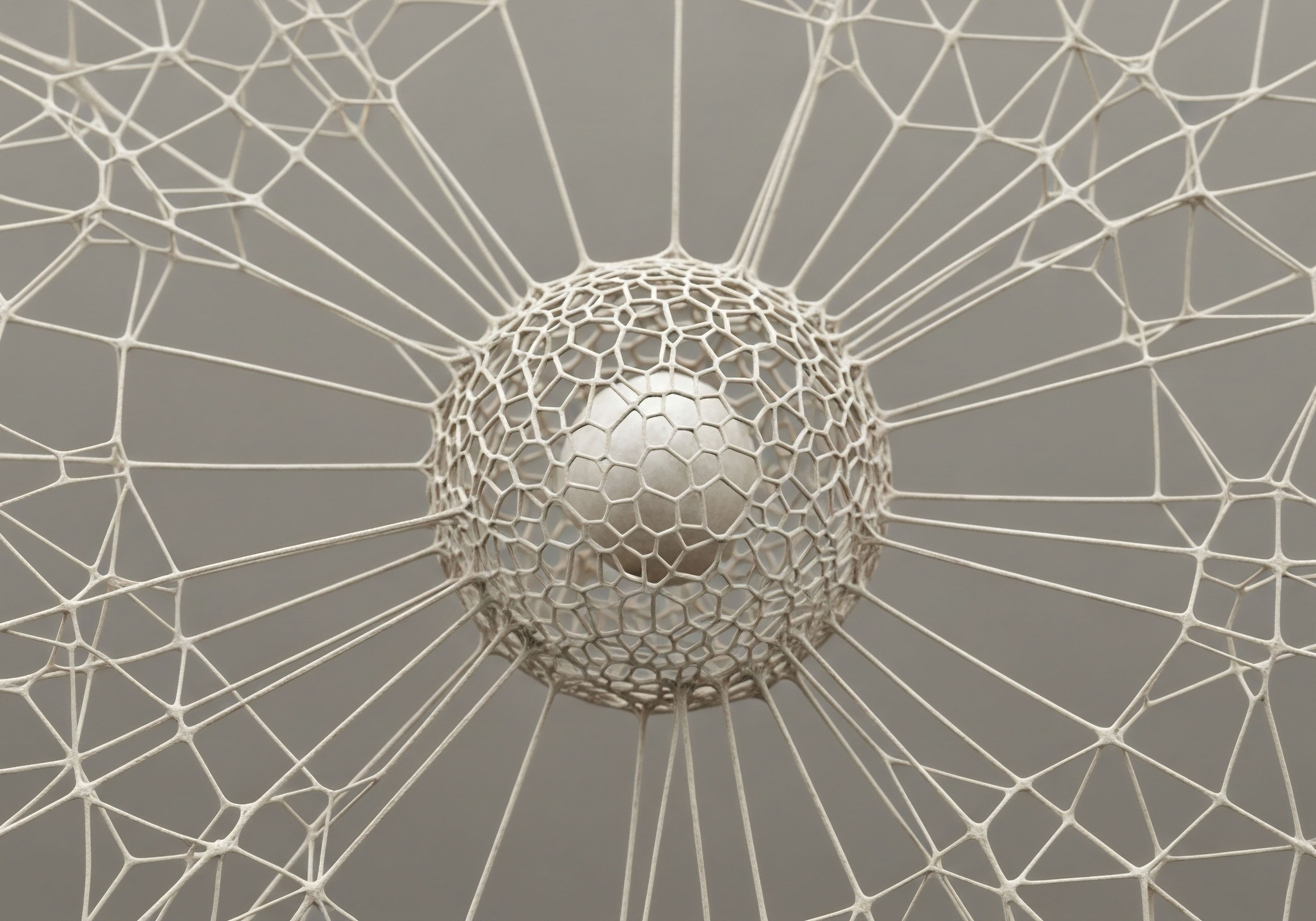

A deeper, more technical analysis reveals that the emotional lability of perimenopause is a complex interplay between the fluctuating Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis and its downstream effects on neurotransmitter systems and neurosteroid activity. The variability of estradiol, more so than its absolute decline, appears to be a key driver of symptoms.

This high variability disrupts the homeostatic function of neural circuits that have, for decades, been accustomed to predictable, cyclical hormonal inputs. Lifestyle interventions, from this academic perspective, can be viewed as allostatic modulators that enhance the resilience of these circuits to hormonal chaos.

Neurosteroids and GABAergic Tone

The conversation about perimenopausal mood must extend to neurosteroids, particularly allopregnanolone. A metabolite of progesterone, allopregnanolone is a potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor, the primary inhibitory receptor in the central nervous system. Its action is analogous to that of benzodiazepines, promoting a state of calm and reducing neuronal excitability.

During the luteal phase of a regular menstrual cycle, rising progesterone leads to elevated allopregnanolone levels, contributing to a sense of tranquility. The erratic progesterone production and anovulatory cycles common in perimenopause lead to a sharp and unpredictable decline in allopregnanolone. This “withdrawal” can result in a state of diminished GABAergic tone, manifesting as anxiety, irritability, and insomnia.

Lifestyle interventions can influence this pathway. For instance, vigorous exercise has been demonstrated to increase allopregnanolone levels, potentially compensating for some of the decline from ovarian sources. Furthermore, certain dietary components and practices that support gut health can influence neurosteroid metabolism, as the gut microbiome plays a role in steroid hormone conversion.

The withdrawal of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone during perimenopause significantly reduces GABAergic inhibition in the brain, leading to a state of heightened neuronal excitability that manifests as anxiety and irritability.

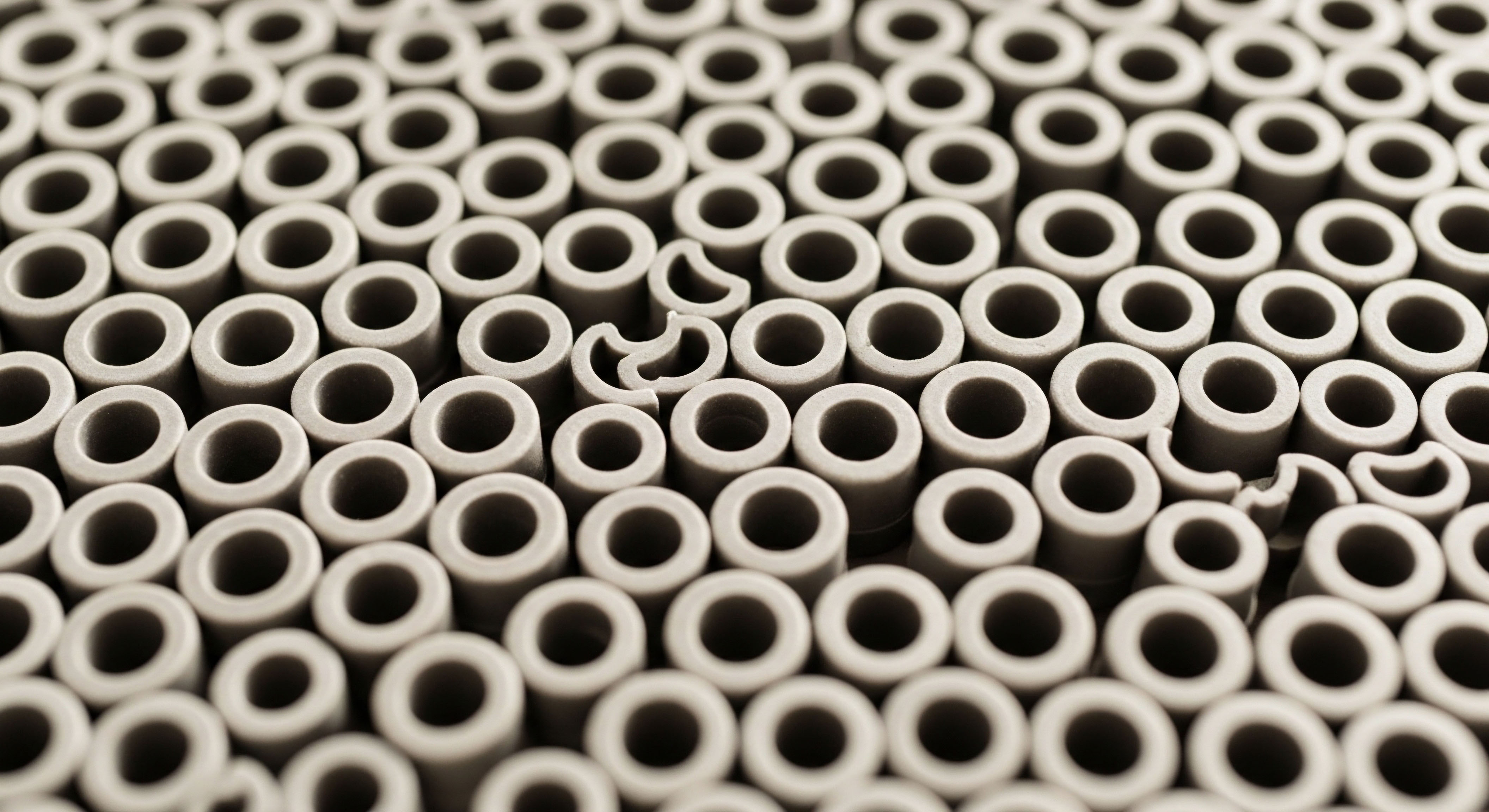

How Does Brain Bioenergetics Shift?

Recent neuroimaging research highlights another critical factor ∞ a shift in brain bioenergetics. Estradiol is a key regulator of cerebral glucose metabolism. As estrogen levels decline, the brain’s ability to utilize glucose as its primary fuel source becomes less efficient.

This can lead to a state of localized hypo-metabolism, particularly in brain regions critical for memory and executive function, contributing to the cognitive “fog” many women experience. This energy deficit can also impact mood-regulating circuits. Lifestyle interventions directly target this bioenergetic challenge.

- Ketogenic Diets ∞ By shifting the body’s primary fuel source from glucose to ketones, a ketogenic or ketone-supporting diet provides the brain with an alternative, highly efficient energy source. This may bypass the glucose utilization deficit and restore energetic balance to affected brain regions.

- Intermittent Fasting ∞ Caloric restriction and fasting protocols have been shown to upregulate BDNF and promote mitochondrial biogenesis, the creation of new mitochondria. This enhances the overall energy-producing capacity of neurons, making them more resilient to the challenges of hormonal transition.

- High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) ∞ This form of exercise is particularly effective at improving mitochondrial efficiency and stimulating the production of lactate, which can also be used by the brain as an energy substrate.

The following table provides a comparative analysis of how different intervention categories impact key neurobiological systems affected during perimenopause.

| Intervention Category | Primary Target System | Key Biomolecular Effects | Associated Symptom Relief |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Ketosis | Brain Bioenergetics | Provides ketones as an alternative fuel; reduces neuroinflammation. | Cognitive Fog, Mood Instability |

| Targeted Exercise (HIIT/Resistance) | Neurogenesis & Metabolism | Increases BDNF, improves insulin sensitivity, boosts lactate production. | Depressive Symptoms, Brain Fog |

| Mind-Body Practices (Yoga/Meditation) | HPA Axis & GABA System | Lowers cortisol, increases parasympathetic tone, potentially modulates GABA receptor sensitivity. | Anxiety, Irritability, Insomnia |

| Phytoestrogen-Rich Diet | Estrogen Receptor Modulation | Provides weak estrogenic activity, potentially buffering receptor signaling from sharp declines. | Vasomotor Symptoms, Mood Swings |

These interventions, therefore, are not superficial fixes. They are sophisticated biological tools that can directly counteract the specific neuro-metabolic and neurochemical disruptions of the perimenopausal transition. By supporting brain energy, enhancing neuroplasticity, and re-establishing inhibitory tone, they help the brain adapt to its new hormonal milieu, thereby stabilizing mood and mitigating other associated neurological symptoms.

References

- Soares, C. N. “Depression and Menopause ∞ An Update on Current Knowledge and Clinical Management for this Critical Window.” The Medical clinics of North America, vol. 103, no. 4, 2019, pp. 651-667.

- Gogos, Andrea, et al. “The role of allopregnanolone in the human brain.” Neuroscience, vol. 30, 2012, pp. 125-141.

- Mosconi, L. et al. “Menopause impacts human brain structure, connectivity, energy metabolism, and amyloid-beta deposition.” Scientific reports, vol. 11, no. 1, 2021, p. 10867.

- Gordon, B. R. et al. “The effects of exercise on cognitive function and brain-derived neurotrophic factor.” Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, vol. 80, 2017, pp. 441-452.

- Hantsoo, L. & Epperson, C. N. “Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder ∞ Epidemiology and Treatment.” Current psychiatry reports, vol. 17, no. 11, 2015, p. 87.

- Freeman, E. W. et al. “Associations of depression with menstruation and menopause.” Journal of Women’s Health, vol. 23, no. 5, 2014, pp. 386-394.

- Grindler, N. M. & Santoro, N. “Menopause and exercise.” Menopause, vol. 22, no. 12, 2015, pp. 1351-1358.

- Maki, P. M. & Henderson, V. W. “Hormone therapy and cognitive function.” The Lancet. Neurology, vol. 11, no. 9, 2012, pp. 741-743.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

You have now seen the intricate connections between your hormones, your brain chemistry, and the way you feel day to day. This knowledge is more than just information; it is the foundational map for your personal health journey. The symptoms you experience are real, biologically driven signals from a body in transition.

The interventions discussed here are the tools you can use to respond to those signals with intention and precision. Your path forward is one of active participation, of listening to your body’s unique feedback and making informed adjustments. The goal is a recalibrated system, where vitality and function are restored not by fighting the change, but by intelligently navigating it.

Glossary

brain chemistry

estrogen levels

nervous system

mood swings

neuro-hormonal mechanisms

lifestyle interventions

phytoestrogens

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

cognitive fog

hpa axis

allopregnanolone

gabaergic tone