Fundamentals

Your body is an intricate, responsive system, a conversation between billions of cells moderated by chemical messengers. You feel this conversation as your daily reality ∞ your energy, your mood, your resilience. During perimenopause, the vocabulary of this internal dialogue begins to shift. The established rhythms of your reproductive hormones, primarily estrogen and progesterone, become unpredictable.

This is a recognized biological transition, a recalibration of your endocrine architecture. It is a period of profound change, and into this delicate state, we introduce an external force ∞ the modern wellness industry. Specifically, we must consider the impact of programs that operate through coercion, rigidity, and shame.

You may have encountered them. They promise a singular path to health, a set of inflexible rules governing food, exercise, and even thought. They imply that any deviation is a personal failure, that your body is a problem to be solved through discipline.

The lived experience of this pressure, this constant low-grade threat of ‘not doing enough,’ is a potent biological stressor. This is not a perceived weakness; it is a physiological fact. The question then becomes a deeply personal and clinical one ∞ can this specific type of stress, the kind born from a coercive wellness Meaning ∞ Coercive wellness signifies the imposition of health behaviors through pressure, not voluntary choice. program, actively worsen the symptoms you are already navigating during perimenopause?

The answer is rooted in the body’s two primary operating systems for managing life ∞ the reproductive axis and the stress-response axis. Think of them as two distinct, yet interconnected, governmental departments. The first is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, the system responsible for reproductive function.

It is the source of the hormonal ebb and flow that defines the menstrual cycle. The hypothalamus, a small region in your brain, acts as the command center, sending signals to the pituitary gland, which in turn directs the ovaries to produce estrogen and progesterone.

During perimenopause, the signals from the command center may remain strong, but the response from the ovaries becomes less consistent. This creates the characteristic fluctuations that lead to symptoms like hot flashes, sleep disruption, and mood changes. It is a system in flux, seeking a new equilibrium.

The second system is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. This is your body’s emergency broadcast system, its mechanism for responding to threats. When your brain perceives a stressor ∞ whether it is a genuine physical danger or the psychological pressure of a restrictive diet and demanding exercise regimen ∞ the hypothalamus releases a signal.

This prompts the pituitary to alert the adrenal glands, situated atop your kidneys, to release cortisol. Cortisol is the body’s primary stress hormone. Its job is to prepare you for immediate action by mobilizing energy. It raises blood sugar, increases alertness, and diverts resources away from what it deems non-essential functions.

In the short term, this is a brilliant survival mechanism. The core of our investigation lies in what happens when this emergency system is chronically activated by the persistent, psychological stress of a coercive wellness program, at the exact time the HPG axis Meaning ∞ The HPG Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine pathway regulating human reproductive and sexual functions. is undergoing its own sensitive transformation. The two systems do not operate in isolation; they are in constant communication, and their collision can amplify the very symptoms you are trying to alleviate.

The Architecture of Hormonal Communication

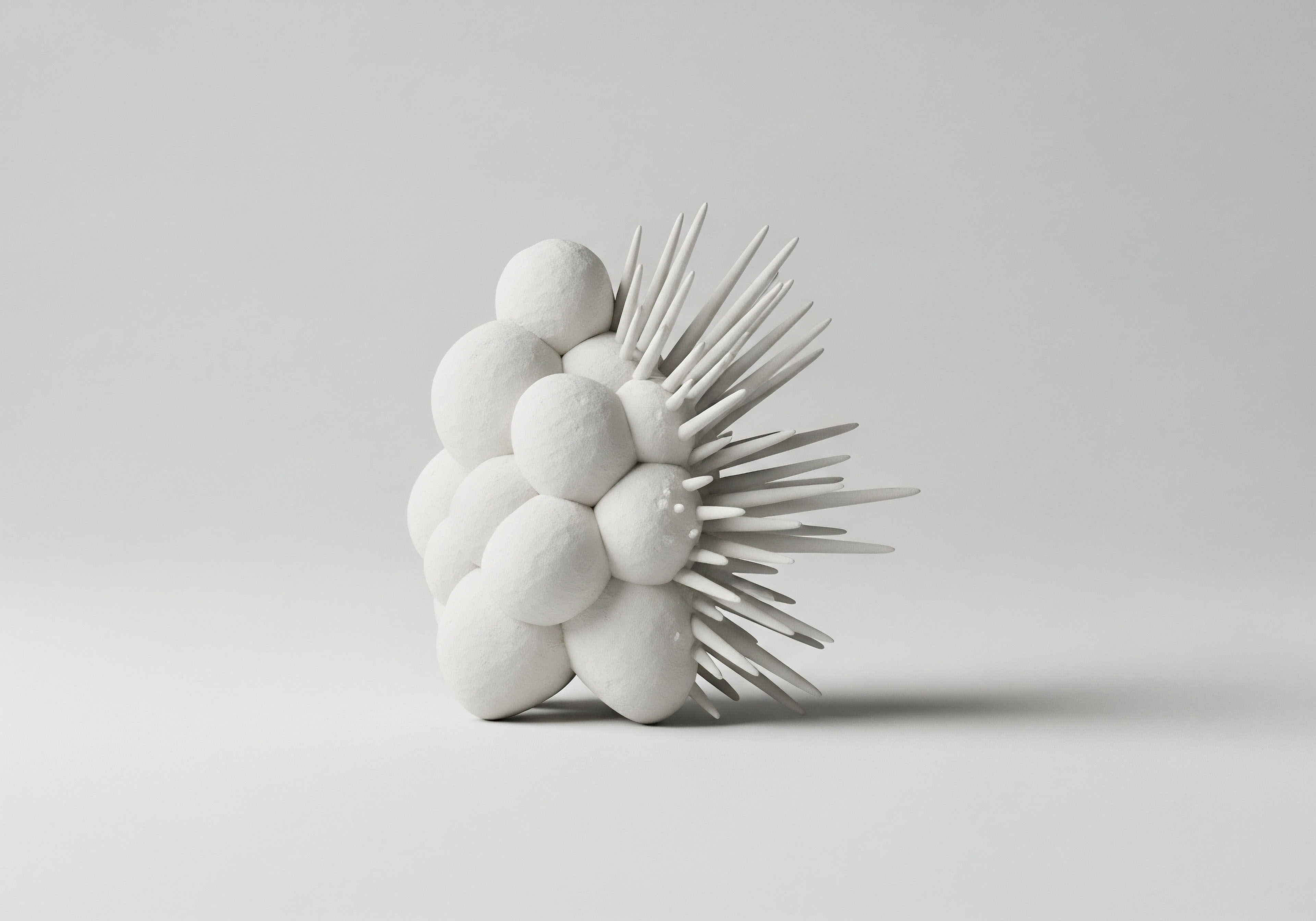

To truly grasp the implications of this collision, we must visualize the body’s hormonal network. It is a system of exquisite sensitivity, built on feedback loops. Imagine the HPG axis as a sophisticated thermostat system for your reproductive health.

The hypothalamus sets the desired temperature, the pituitary acts as the control panel, and the ovaries are the furnace, producing the ‘heat’ in the form of hormones. These hormones then signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary, informing them that the target has been met, which in turn quiets the initial signal.

It is a self-regulating, elegant loop. Perimenopause introduces static into this system. The furnace becomes less reliable, sometimes running too hot, sometimes too cold, and the feedback signals become erratic. The entire system is working harder to maintain balance.

Now, introduce the HPA axis, which acts as an overriding emergency protocol. When cortisol is released, it is a system-wide alert. Its primary directive is survival. This means it has the authority to interrupt or modify the functions of other systems, including the HPG axis.

Cortisol can directly suppress the signaling from the hypothalamus and pituitary to the ovaries. From a biological standpoint, this makes sense; in a time of perceived famine or danger (which is how a highly restrictive program can be interpreted by the body), reproduction is a low priority.

The body’s resources are shunted towards immediate survival, a state of high alert. The chronic activation of this stress pathway means the ’emergency’ signal never truly turns off. The HPG axis, already struggling to find its new rhythm, is now constantly being interrupted and suppressed by the persistent chemical shout of cortisol. This interference is a central mechanism by which a stressful wellness program Meaning ∞ A Wellness Program represents a structured, proactive intervention designed to support individuals in achieving and maintaining optimal physiological and psychological health states. can directly exacerbate the symptomatic experience of perimenopause.

What Defines a Coercive Wellness Program?

It is important to differentiate between supportive, health-promoting practices and coercive ones. A coercive program often exhibits specific characteristics that are themselves sources of psychological and physiological stress. Understanding these traits allows you to identify the source of the pressure you may be feeling.

These programs often present a one-size-fits-all ideology, promoting a single ‘correct’ way to eat or exercise, ignoring individual biochemistry, genetics, and life circumstances. This rigidity creates a pass/fail dynamic where any deviation leads to feelings of guilt and failure, which are potent psychological stressors.

Furthermore, these programs frequently rely on shame and comparison as motivational tools. Public weigh-ins, leaderboards, or the implicit pressure of social media feeds curated to show only ‘success’ can activate the HPA axis. The fear of judgment or of falling behind becomes a chronic threat.

This transforms the act of self-care into a performance, a form of labor that adds to your allostatic load Meaning ∞ Allostatic load represents the cumulative physiological burden incurred by the body and brain due to chronic or repeated exposure to stress. ∞ the cumulative wear and tear on the body from chronic stress. They also tend to promote extreme protocols, such as severe caloric restriction or excessive high-intensity exercise.

While presented as paths to rapid results, these are interpreted by the body as significant physiological stressors. A severely restricted diet mimics a famine state, and excessive exercise signals a need to flee danger, both of which are powerful triggers for cortisol production. This creates a situation where the very actions taken to improve well-being become the primary drivers of hormonal disruption.

The Perimenopausal Body under Chronic Stress

When the body is in the midst of the perimenopausal transition, its resilience to stress is already being tested. The natural decline in estrogen and progesterone Meaning ∞ Estrogen and progesterone are vital steroid hormones, primarily synthesized by the ovaries in females, with contributions from adrenal glands, fat tissue, and the placenta. has wide-ranging effects. Estrogen, for example, helps to modulate cortisol levels and supports the function of neurotransmitters like serotonin, which regulates mood.

As estrogen levels fluctuate and decline, the body’s natural buffer against stress is diminished. Symptoms like anxiety, irritability, and poor sleep are common results of these hormonal shifts. They are the direct consequence of changes within the HPG axis and its influence on the central nervous system.

A coercive wellness program, by inducing a state of chronic stress, pours fuel on this existing fire.

The elevated cortisol resulting from the program’s demands can directly worsen the very symptoms that define the perimenopausal experience. For instance, both perimenopausal hormonal shifts Meaning ∞ Perimenopause is the transitional phase preceding menopause, marked by irregular menstrual cycles and fluctuating ovarian hormone production. and high cortisol can lead to insomnia. The combination makes restful sleep exceptionally difficult to achieve.

Cortisol is meant to be highest in the morning to promote wakefulness and lowest at night to allow for sleep. Chronic stress Meaning ∞ Chronic stress describes a state of prolonged physiological and psychological arousal when an individual experiences persistent demands or threats without adequate recovery. disrupts this rhythm, keeping cortisol levels Meaning ∞ Cortisol levels refer to the quantifiable concentration of cortisol, a primary glucocorticoid hormone, circulating within the bloodstream. elevated in the evening, preventing the body from winding down.

This lack of sleep, in turn, is another major stressor, further increasing cortisol levels the next day and creating a vicious cycle of fatigue and hyper-arousal. This is not a matter of willpower; it is a biochemical loop that is difficult to exit without addressing the root cause of the stress.

Similarly, consider the metabolic changes. Perimenopause is often associated with a shift in body composition, including an increase in visceral fat Meaning ∞ Visceral fat refers to adipose tissue stored deep within the abdominal cavity, surrounding vital internal organs such as the liver, pancreas, and intestines. around the abdomen. This is partly due to the changing ratio of estrogen to androgens. Cortisol also promotes the storage of visceral fat.

A coercive program that causes chronic stress can therefore accelerate this specific type of weight gain, even if you are adhering to a restrictive diet and exercise Meaning ∞ Diet and exercise collectively refer to the habitual patterns of nutrient consumption and structured physical activity undertaken to maintain or improve physiological function and overall health status. plan. The frustration of seeing your body change in a way that feels opposite to your efforts can then become another source of stress, further tightening the cycle. The program, sold as a solution, becomes an integral part of the problem. Recognizing this dynamic is the first step toward reclaiming your biological autonomy.

Intermediate

To comprehend how a coercive wellness program A legally coercive wellness program is one that imposes a biological cost, dysregulating your hormones and undermining health. can biologically antagonize the perimenopausal body, we must move beyond a generalized concept of stress and examine the specific biochemical pathways at play. The interaction is a story of molecular competition, signaling interference, and resource depletion, occurring at the precise moment when the body’s endocrine system is least equipped to handle the assault.

The core of this conflict is the functional crosstalk between the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, our stress response system, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, our reproductive system. These are not two separate entities; they are deeply integrated, sharing common neural origins and regulatory mechanisms. Chronic activation of one has direct, predictable consequences for the other.

A coercive wellness program, with its rigid dietary rules, excessive exercise demands, and psychological pressure, is a potent, multi-faceted activator of the HPA axis. The brain interprets this sustained state of high alert and deprivation as a threat to homeostasis. This triggers a cascade beginning in the hypothalamus with the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH).

CRH signals the pituitary to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol. Simultaneously, CRH has another, more direct effect ∞ it inhibits the release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus.

GnRH is the master regulator of the HPG axis; it is the primary signal that initiates the entire sequence of events leading to ovulation and the production of estrogen and progesterone. By suppressing GnRH, chronic stress directly throttles the reproductive axis at its source.

During perimenopause, when GnRH signals are already attempting to overcome the ovaries’ diminishing response, this added layer of suppression can significantly amplify hormonal chaos, leading to more erratic cycles, heightened vasomotor symptoms Meaning ∞ Vasomotor symptoms, commonly known as hot flashes and night sweats, are transient sensations of intense heat affecting the face, neck, and chest, often with profuse perspiration. (hot flashes), and intensified mood fluctuations.

The Pregnenolone Steal Hypothesis Revisited

A frequently discussed mechanism in integrative medicine is the concept of “pregnenolone steal.” While the term itself can be an oversimplification, the underlying principle is biochemically sound and highly relevant here. Pregnenolone is a precursor hormone, synthesized from cholesterol. It sits at a crucial metabolic crossroads, capable of being converted down one of two major pathways.

One path leads to the production of progesterone, a key reproductive hormone. The other path leads to the production of cortisol. Under conditions of chronic stress, the body’s demand for cortisol becomes relentless. The enzymes that facilitate the conversion of pregnenolone into the precursors for cortisol are upregulated. Consequently, a greater proportion of the available pregnenolone pool is shunted down the cortisol production line. This leaves less substrate available for the production of progesterone.

In the context of perimenopause, this is a critical issue. Progesterone levels are already declining and becoming more erratic. Progesterone has a calming, balancing effect on the nervous system; it promotes sleep and stabilizes mood, in part by acting on GABA receptors in the brain.

The further depletion of progesterone due to the chronic cortisol demand from a coercive wellness program can therefore directly worsen symptoms of anxiety, irritability, and insomnia. The body, in its effort to manage the perceived threat of the wellness program, sacrifices the very hormone that would provide a sense of calm and stability. This is a clear example of how a psychological stressor creates a tangible, symptom-worsening biochemical deficit.

How Does Stress Derail Metabolic Health in Perimenopause?

One of the most distressing symptoms for many women in perimenopause is a change in metabolic health, often manifesting as weight gain, particularly around the midsection, and a feeling that the body is resistant to previous diet and exercise efforts. A coercive wellness program can paradoxically accelerate these unwanted changes through the actions of cortisol on insulin sensitivity.

Cortisol’s primary metabolic role during stress is to ensure a ready supply of glucose for the brain and muscles. It does this by promoting gluconeogenesis in the liver (the creation of new glucose) and by making peripheral tissues, like muscle cells, more resistant to the effects of insulin.

This insulin resistance Meaning ∞ Insulin resistance describes a physiological state where target cells, primarily in muscle, fat, and liver, respond poorly to insulin. prevents muscle cells from taking up too much glucose, saving it for the brain. In an acute stress situation, this is adaptive. When stress is chronic, it leads to persistently high blood glucose levels and sustained insulin resistance.

The collision of perimenopausal hormonal shifts with stress-induced metabolic changes creates a perfect storm for abdominal weight gain.

The perimenopausal decline in estrogen already contributes to a natural decrease in insulin sensitivity. When you layer the insulin-desensitizing effects of chronic cortisol on top of this, the body’s ability to manage blood sugar is significantly impaired. The pancreas responds by producing even more insulin to try to overcome the resistance, a condition known as hyperinsulinemia.

High levels of insulin are a powerful signal for the body to store fat, especially in the abdominal region. The very program designed to achieve fat loss thus creates the precise hormonal environment that promotes it. This biochemical reality explains why a woman following a restrictive diet and intense exercise regimen under duress may see her body composition worsen, a deeply frustrating experience that further fuels the stress cycle.

The following table illustrates the compounding effect of perimenopausal changes and chronic stress on common symptoms:

| Perimenopausal Symptom | Underlying Hormonal Shift (HPG Axis) | Compounding Effect of Chronic Stress (HPA Axis Activation) | Resulting Lived Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insomnia & Poor Sleep |

Declining progesterone, which has sedative properties, disrupts sleep architecture. |

Elevated evening cortisol disrupts the natural circadian rhythm, promoting a state of hyper-arousal at night. |

Difficulty falling asleep, frequent waking, and non-restorative sleep, leading to profound daytime fatigue. |

| Mood Swings & Anxiety |

Fluctuating estrogen impacts serotonin and dopamine levels. Declining progesterone reduces GABAergic (calming) activity. |

Chronic CRH and cortisol deplete neurotransmitter precursors and can directly induce feelings of anxiety and hypervigilance. |

Heightened feelings of irritability, inexplicable sadness, and a persistent, low-level sense of dread or panic. |

| Abdominal Weight Gain |

Shift in estrogen-to-androgen ratio and decreased insulin sensitivity promote visceral fat storage. |

Cortisol directly promotes visceral adiposity and significantly worsens insulin resistance, leading to hyperinsulinemia. |

Increased fat accumulation around the midsection, despite adherence to diet and exercise, fueling frustration. |

| Brain Fog & Poor Memory |

Estrogen plays a key role in neuronal health and connectivity in the hippocampus, a key memory center. |

Chronic high levels of glucocorticoids are known to be toxic to hippocampal neurons, impairing memory formation and recall. |

Difficulty with word retrieval, short-term memory lapses, and a general feeling of cognitive slowness. |

The Disruption of Thyroid and DHEA Balance

The endocrine system is a web, and pulling on one thread inevitably tugs on all the others. The chronic HPA axis Meaning ∞ The HPA Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine system orchestrating the body’s adaptive responses to stressors. activation caused by a coercive wellness program extends its disruptive influence to other critical hormonal systems, notably the thyroid and the production of DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone).

Your thyroid gland is the master regulator of your metabolic rate. For your body to use thyroid hormone effectively, the inactive form (T4) must be converted to the active form (T3). High levels of cortisol inhibit this conversion. Instead, the body favors the conversion of T4 into reverse T3 (rT3), an inactive metabolite that essentially blocks thyroid receptors.

This can induce a state of functional hypothyroidism, where blood tests for TSH and T4 may appear normal, but the body is not getting the active thyroid hormone it needs. The symptoms are classic ∞ fatigue, weight gain, hair loss, and feeling cold ∞ symptoms that overlap significantly with and worsen the perimenopausal experience.

Simultaneously, the adrenal glands produce another crucial hormone ∞ DHEA. DHEA is often referred to as an “anti-stress” hormone, as it buffers many of the negative effects of cortisol. It supports insulin sensitivity, promotes a healthy immune response, and is a precursor to sex hormones like testosterone, which is vital for libido, bone density, and muscle mass in women.

During chronic stress, while cortisol production is prioritized, DHEA production can decline. The ratio of cortisol to DHEA becomes skewed, a key biomarker of long-term HPA axis dysfunction. A high cortisol-to-DHEA ratio is a physiological signature of allostatic load.

This imbalance further robs the perimenopausal woman of the very hormonal support she needs to navigate this transition, diminishing her resilience and amplifying symptoms of fatigue and low libido. A wellness program that induces this state is actively undermining the body’s innate capacity for balance and vitality.

- GnRH Suppression ∞ The brain’s primary stress hormone, CRH, directly inhibits the release of GnRH, the master controller of the reproductive system. This dampens the entire HPG axis, making hormonal fluctuations more severe.

- Progesterone Depletion ∞ The body’s raw materials, like pregnenolone, are preferentially diverted to produce cortisol to manage chronic stress, leaving less available for the production of calming progesterone.

- Insulin Resistance ∞ Chronically elevated cortisol makes the body’s cells less responsive to insulin, promoting high blood sugar and signaling the body to store fat, particularly in the abdominal area.

- Thyroid Inhibition ∞ Stress hormones block the conversion of inactive thyroid hormone (T4) to its active form (T3), slowing metabolism and causing fatigue and weight gain.

- DHEA Depletion ∞ The adrenal glands’ capacity to produce the beneficial, cortisol-buffering hormone DHEA is diminished under chronic stress, reducing resilience and impacting libido and energy.

Academic

The deleterious synergy between the psychosocial stress of a coercive wellness program and the neurobiological flux of perimenopause can be understood through the lens of allostatic overload. Allostasis, the process of achieving stability through physiological change, is adaptive.

Allostatic overload, however, describes the pathogenic state that emerges when the cost of this adaptation becomes too high, leading to cumulative “wear and tear” on the body’s systems. Perimenopause itself can be conceptualized as a period of heightened allostasis, as the neuroendocrine system attempts to adapt to the progressive decline of ovarian follicular competence.

The imposition of a chronic, non-negotiable stressor, such as a wellness regimen predicated on restriction and shame, pushes this already taxed system into a state of allostatic overload, with measurable consequences for neuroendocrine function, metabolic health, and inflammatory status.

The central mechanism mediating this interaction is the bidirectional communication between the HPA and HPG axes. This crosstalk is not merely inhibitory; it is a complex modulation that occurs at multiple levels, from the hypothalamus down to the peripheral glands. The primary inhibitory pressure of stress on reproduction is exerted by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH).

CRH neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus project to and inhibit the function of GnRH neurons in the preoptic area. This effect is compounded by the action of glucocorticoids, which decrease the sensitivity of pituitary gonadotrophs to GnRH stimulation, thereby reducing the secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

During perimenopause, the pituitary is already increasing its output of FSH in an attempt to stimulate a less responsive ovary. The suppressive effect of glucocorticoids on pituitary sensitivity represents a direct countermeasure to this compensatory mechanism, effectively thwarting the body’s attempt to maintain hormonal equilibrium.

Glucocorticoid Receptor Sensitivity and Neuroinflammation

A critical factor in this dynamic is the change in glucocorticoid receptor Meaning ∞ The Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) is a nuclear receptor protein that binds glucocorticoid hormones, such as cortisol, mediating their wide-ranging biological effects. (GR) sensitivity during the perimenopausal transition. Estrogen is known to modulate the expression and function of GRs within key brain regions, including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. As estrogen levels become erratic and decline, the regulation of these receptors can be disrupted.

This can lead to a state of central glucocorticoid resistance, where the brain’s negative feedback control over the HPA axis becomes impaired. The hippocampus, which is dense with GRs, normally functions to inhibit HPA axis activity once cortisol levels rise.

Chronic stress itself can downregulate GRs in the hippocampus, but this effect may be amplified by the loss of estrogen’s protective and regulatory influence. The result is a feed-forward loop ∞ stress becomes less effective at shutting itself off, leading to prolonged periods of hypercortisolemia.

This sustained hypercortisolemia has profound implications for brain health, particularly in the context of neuroinflammation. Glucocorticoids, while acutely anti-inflammatory, can have pro-inflammatory effects in the brain when chronically elevated. They can prime microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, to respond more aggressively to subsequent stimuli.

Perimenopause is independently associated with a more pro-inflammatory state, sometimes termed “inflammaging.” The combination of declining estrogen, which has anti-inflammatory properties in the brain, and rising cortisol creates a potent pro-inflammatory milieu. This neuroinflammatory state is increasingly implicated in the etiology of perimenopausal mood disorders, cognitive complaints (“brain fog”), and even the genesis of vasomotor symptoms.

A coercive wellness program, by sustaining hypercortisolemia, is therefore not just adding “stress”; it is contributing to a quantifiable increase in the inflammatory load on the central nervous system, directly fueling the neurological symptoms of perimenopause.

What Is the Impact on Metabolic Flexibility?

Metabolic flexibility refers to the ability of an organism to efficiently switch between fuel sources, primarily glucose and fatty acids, in response to metabolic demands. This capacity is fundamental to metabolic health. Both perimenopause and chronic stress are potent disruptors of metabolic flexibility.

The decline in estrogen during perimenopause is associated with a shift toward glucose utilization and impaired fatty acid oxidation, contributing to the accumulation of intramyocellular lipids and insulin resistance. Chronic hypercortolemia, as induced by a coercive wellness program, aggressively compounds this issue.

Cortisol promotes a state of “metabolic rigidity.” It ensures high glucose availability through hepatic gluconeogenesis while simultaneously blocking glucose uptake in peripheral tissues and impairing mitochondrial function required for fat burning. The body becomes locked in a state of perceived energy crisis, reliant on glucose but inefficient at using it.

The convergence of perimenopausal hormonal shifts and chronic stress-induced cortisol elevation systematically dismantles metabolic flexibility, fostering a state of energy crisis and fat storage.

This metabolic rigidity explains the clinical observation of perimenopausal women who, despite severe caloric restriction and vigorous exercise, experience an increase in adiposity. The body, under dual hormonal pressure, is unable to access its fat stores for energy.

The restrictive diet is perceived as famine, and the exercise as a threat, causing cortisol to surge and command the body to conserve energy and store any available calories as visceral fat, the most metabolically active and inflammatory type of adipose tissue. The following table provides a conceptual model of biomarker changes one might observe in this state of allostatic overload.

| Biomarker System | Biomarker | Expected Change in Perimenopause | Expected Change Under Coercive Stress | Synergistic Pathological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPA Axis |

Fasting AM Cortisol |

Variable, may increase |

Chronically elevated |

Sustained hypercortisolemia, blunted CAR, hippocampal atrophy |

|

Cortisol/DHEA-S Ratio |

Increases due to age-related DHEA decline |

Sharply increases as cortisol rises and DHEA is suppressed |

Accelerated cellular aging, loss of anabolic buffering |

|

| HPG Axis |

FSH |

Elevated |

No direct effect, but pituitary sensitivity to GnRH is reduced |

Ineffective pituitary compensation for ovarian decline |

|

Progesterone (Luteal) |

Decreased and erratic |

Further decreased due to pregnenolone diversion |

Severe exacerbation of anxiety, insomnia, and mood lability |

|

| Metabolic Markers |

Fasting Insulin / HOMA-IR |

Increases |

Significantly increases |

Rapid onset of severe insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome |

|

Triglycerides |

Tend to increase |

Increase due to insulin resistance |

Dyslipidemia and increased cardiovascular risk |

|

| Inflammatory Markers |

hs-CRP / IL-6 |

Tend to increase |

Increase due to chronic stress and visceral adiposity |

Systemic, low-grade inflammation fueling multi-system dysfunction |

The Autonomic Nervous System and Vasomotor Symptoms

Finally, the role of the autonomic nervous system Optimize your nervous system; it’s the real high-performance lab for unparalleled vitality and longevity. (ANS) must be considered. Hot flashes, or vasomotor symptoms, are not merely a consequence of estrogen withdrawal. They are complex neurovascular events orchestrated by the hypothalamus, involving a sudden, inappropriate activation of the sympathetic nervous system (the “fight or flight” branch of the ANS).

This leads to peripheral vasodilation, a surge in heart rate, and the subjective sensation of intense heat. The precise trigger is thought to be a narrowing of the thermoneutral zone in the hypothalamus, making the body exquisitely sensitive to small fluctuations in core body temperature.

Chronic stress, by its very nature, creates a state of sympathetic dominance. Elevated levels of catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine), alongside cortisol, keep the ANS in a state of high alert. For a perimenopausal woman, this means her baseline nervous system Meaning ∞ The Nervous System represents the body’s primary communication and control network, composed of the brain, spinal cord, and an extensive array of peripheral nerves. tone is already shifted toward the sympathetic end of the spectrum.

Her narrowed thermoneutral zone is now operating within an environment of heightened sympathetic drive. This makes the triggering of a vasomotor episode far more likely and potentially more severe. The psychological stress of failing to meet a program’s rigid standards can, in itself, be enough to trigger a sympathetic surge that pushes the body’s core temperature just outside the narrow zone of tolerance, initiating a hot flash.

In this way, the coercive wellness program becomes a direct, real-time trigger for one of the most disruptive symptoms of perimenopause, illustrating a clear and demonstrable link between external psychological pressure and internal physiological breakdown.

- Allostatic Overload ∞ The cumulative physiological burden of chronic stress, which, when layered upon the biological transition of perimenopause, accelerates cellular aging and disease risk.

- Glucocorticoid Resistance ∞ A state, often developing in the brain during chronic stress, where cells become less sensitive to cortisol’s signal, impairing the negative feedback loop that should shut down the stress response and leading to prolonged hypercortisolemia.

- Neuroinflammation ∞ An inflammatory state within the central nervous system, driven by both declining estrogen and elevated cortisol, which contributes to mood disorders and cognitive dysfunction.

- Metabolic Rigidity ∞ A pathological state where the body loses its ability to efficiently switch between burning carbohydrates and fats for fuel, leading to insulin resistance and fat storage.

- Sympathetic Dominance ∞ A chronic state of over-activation of the “fight or flight” branch of the autonomic nervous system, which increases the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms like hot flashes.

References

- Viau, V. “Functional cross-talk between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and -adrenal axes.” Journal of Neuroendocrinology, vol. 14, no. 6, 2002, pp. 506-513.

- Woods, N. F. et al. “Cortisol levels during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause ∞ observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study.” Menopause, vol. 16, no. 4, 2009, pp. 708-718.

- McEwen, B. S. “Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 840, 1998, pp. 33-44.

- Ranabir, S. and K. Reetu. “Stress and hormones.” Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 15, no. 1, 2011, pp. 18-22.

- Stark, E. “Coercive control ∞ How men entrap women in personal life.” Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Herman, J. L. “Trauma and recovery ∞ The aftermath of violence–from domestic abuse to political terror.” BasicBooks, 1992.

- Sapolsky, R. M. L. M. Romero, and A. U. Munck. “How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 21, no. 1, 2000, pp. 55-89.

- Gourley, S. L. and J. R. Taylor. “Going and coming ∞ crack-cocaine and the prefrontal cortex.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1167, 2009, pp. 51-64.

- Juster, R. P. B. S. McEwen, and S. J. Lupien. “Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition.” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 34, no. 1, 2010, pp. 2-16.

- Lovallo, W. R. “Cortisol and heart disease ∞ a new look at an old story.” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 73, no. 9, 2011, pp. 719-720.

Reflection

You have now traveled through the intricate biological landscape where your internal hormonal transition meets the external pressures of modern life. The information presented here is a map, detailing the mechanisms and pathways that connect a feeling of pressure to a tangible physiological reality.

It validates the lived experience that a program intended for well-being can become a source of profound distress, particularly during the sensitive window of perimenopause. This knowledge is a form of power. It allows you to re-frame your experience, moving from self-blame to biological understanding. It provides a new lens through which to evaluate the messages you receive about health, wellness, and your own body.

The purpose of this deep exploration is to equip you with a more sophisticated understanding of your own internal architecture. Your body is not a machine to be disciplined into submission; it is a responsive, intelligent system striving for balance.

The symptoms you experience are signals, a form of communication from that system about its current state and its needs. Learning to listen to these signals, to understand their origin, is the foundational step in navigating this transition with agency and grace.

The path forward is one of personalization, of aligning your actions with your unique biology rather than conforming to an external, arbitrary set of rules. This journey is yours alone, and it begins with the recognition that your internal wisdom, informed by this clinical knowledge, is your most reliable guide.