Reclaiming Hormonal Equilibrium through Movement

Many individuals experience a subtle yet pervasive decline in vitality, a creeping lassitude that often correlates with modern, desk-bound existences. You might notice a persistent fatigue, shifts in mood, or a recalcitrant accumulation of adipose tissue, even when dietary patterns appear stable.

These sensations are not mere inconveniences; they represent the body’s articulate signals, indicators of a profound dialogue occurring within your biological systems, particularly your endocrine architecture. Your body possesses an inherent intelligence, a remarkable capacity for adaptation, and understanding this principle serves as the first step toward restoring its optimal function.

A sedentary lifestyle casts a long shadow over endocrine functionality. When physical activity diminishes, the body’s intricate hormonal messaging service begins to falter. This system, responsible for orchestrating everything from energy regulation to reproductive health and stress response, thrives on dynamic inputs.

Without the regular demands of movement, its finely tuned feedback loops can become desensitized or dysregulated, leading to a cascade of downstream effects. The body’s innate drive for homeostasis, its stable internal state, is constantly seeking equilibrium, and movement serves as a potent re-calibrating force.

A sedentary lifestyle disrupts the body’s hormonal messaging, diminishing its natural equilibrium.

Understanding the Endocrine Symphony

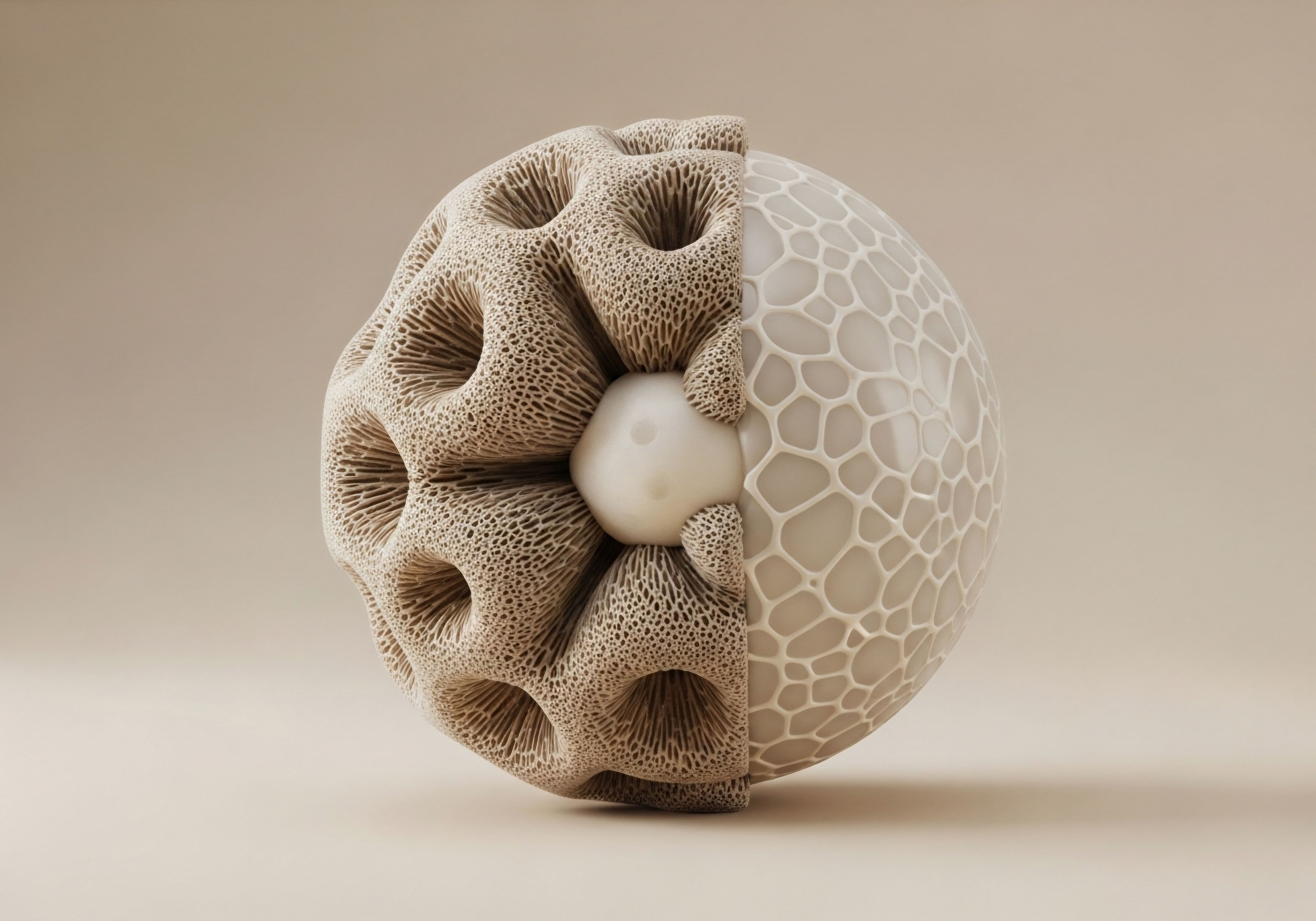

Consider the endocrine system as a grand orchestra, where each hormone represents a specific instrument, playing its part in a harmonious composition. The hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and other endocrine organs function as the conductors, ensuring each section performs its role precisely.

When daily life lacks physical exertion, the instruments can drift out of tune, and the conductors may lose their precise timing. This leads to a suboptimal physiological state, where the body’s internal communications become less efficient. The body yearns for rhythm and stimulation to maintain its intricate internal symphony.

The human organism is designed for motion. Our evolutionary trajectory shaped biological systems that anticipate and benefit from regular physical challenges. When these anticipated stimuli are absent, physiological processes adapt to this new, less demanding environment. This adaptation often manifests as a reduction in metabolic flexibility, a blunted hormonal response, and an overall decrease in the body’s capacity to respond effectively to stressors. Reintroducing structured movement provides the necessary signals to reawaken these dormant capacities.

Initial Steps toward Hormonal Re-Engagement

- Consistent Movement ∞ Begin with daily, sustained low-intensity activity, such as brisk walking, to re-establish fundamental metabolic rhythms.

- Mindful Engagement ∞ Pay attention to how your body responds to movement, observing shifts in energy levels, sleep quality, and mood.

- Gradual Progression ∞ Increase duration and intensity incrementally, allowing your systems to adapt without undue stress.

Clinical Recalibration through Exercise Modalities

Transitioning from a sedentary existence toward a more active one represents a deliberate strategy to recalibrate the endocrine system, a profound act of self-stewardship. This shift involves understanding how distinct exercise modalities interact with specific hormonal pathways, providing targeted stimuli for restoration. The body responds differentially to various forms of physical exertion, necessitating a considered approach to movement protocols.

For instance, resistance training, involving activities that challenge muscular strength, significantly influences growth hormone (GH) secretion and insulin sensitivity. This type of activity creates micro-traumas in muscle fibers, signaling the body to initiate repair and growth processes, which are inherently anabolic. The resulting release of GH supports tissue repair and fat metabolism, while improved insulin sensitivity means cells more effectively utilize glucose, mitigating the metabolic dysregulation often associated with inactivity. This is a direct pathway to enhanced metabolic resilience.

Specific exercise types offer targeted stimuli for endocrine system recalibration.

Exercise and Key Endocrine Axes

Aerobic exercise, characterized by sustained cardiovascular effort, plays a pivotal role in optimizing the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system. Chronic inactivity can lead to HPA axis dysregulation, manifesting as altered cortisol rhythms and diminished stress resilience. Regular aerobic activity helps normalize these rhythms, promoting a healthier diurnal cortisol curve and enhancing the body’s capacity to manage physiological stressors. It acts as a powerful regulator, bringing the stress response system into a more adaptive state.

Furthermore, the impact on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, governing reproductive and sexual health, is substantial. For men experiencing symptoms of low testosterone, a condition sometimes exacerbated by sedentary habits, consistent exercise, particularly resistance training, can stimulate endogenous testosterone production. In women, regular physical activity supports ovarian function and helps modulate estrogen and progesterone balance, addressing concerns such as irregular cycles or symptoms associated with peri-menopause. This systemic influence underscores the interconnectedness of all physiological processes.

| Exercise Type | Primary Hormonal Impact | Metabolic Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Resistance Training | Growth Hormone, Testosterone, Insulin Sensitivity | Muscle protein synthesis, improved glucose uptake |

| Aerobic Activity | Cortisol Rhythm, Endorphins, Catecholamines | Cardiovascular health, stress adaptation, fat oxidation |

| High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) | Growth Hormone, Catecholamines, Insulin Sensitivity | Enhanced fat burning, improved cardiorespiratory fitness |

Integrating Therapeutic Support

While exercise forms a cornerstone of hormonal recalibration, certain clinical protocols can complement and accelerate this process, particularly when significant dysregulation is present. For men with confirmed hypogonadism, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) involving weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate, often combined with Gonadorelin to preserve natural production and fertility, and Anastrozole to manage estrogen conversion, offers a direct path to restoring physiological testosterone levels.

These interventions support the body’s return to an optimal state, allowing exercise to exert its benefits on a more robust foundation.

Women experiencing hormonal imbalances may benefit from tailored protocols. Low-dose Testosterone Cypionate via subcutaneous injection can address symptoms like low libido and energy. Progesterone may be prescribed based on menopausal status to support cyclical balance or mitigate symptoms. These targeted interventions work synergistically with an active lifestyle, providing comprehensive support for endocrine system restoration. The goal remains the same ∞ to re-establish the body’s inherent capacity for balance and vitality.

Clinical protocols can augment exercise, providing direct hormonal support when needed.

Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy, using agents like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin / CJC-1295, can also enhance the body’s restorative capacity. These peptides stimulate the pulsatile release of endogenous growth hormone, supporting muscle gain, fat loss, improved sleep architecture, and tissue repair, all of which are critical for reversing the systemic effects of prolonged inactivity. Such strategies underscore a holistic approach to wellness, where movement, nutrition, and targeted biochemical recalibration work in concert.

Epigenetic Recalibration and Neuroendocrine Plasticity

The notion of reversing hormonal damage transcends simple physiological adjustments; it delves into the profound plasticity of the human system, particularly at the epigenetic and neuroendocrine levels. Chronic sedentarism imposes a state of metabolic inertia, characterized by persistent low-grade inflammation, impaired insulin signaling, and dysregulation across the major neuroendocrine axes. Exercise, viewed through a sophisticated clinical lens, acts as a potent epigenetic modulator and a profound driver of neuroendocrine re-patterning, capable of resetting compromised biological set points.

The cellular machinery responds to mechanical and metabolic stressors induced by physical activity through intricate signaling cascades. Myokines, secreted by contracting muscles, serve as inter-organ communicators, influencing distant tissues like adipose tissue, the liver, and the brain.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6), for instance, is a prominent myokine that, in an acute exercise context, plays a role in glucose uptake and anti-inflammatory processes, a stark contrast to its chronic inflammatory role in sedentary states. This illustrates a profound shift in cellular dialogue, driven by movement.

Exercise profoundly influences epigenetic and neuroendocrine plasticity, resetting biological set points.

Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Metabolic Reprogramming

A central mechanism by which exercise combats metabolic and hormonal damage involves mitochondrial biogenesis. Sedentary lifestyles often lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, characterized by reduced density, impaired respiratory chain function, and increased oxidative stress. Regular physical activity, particularly endurance and high-intensity interval training, stimulates the activation of transcriptional coactivators such as PGC-1α (Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-alpha).

PGC-1α is a master regulator of mitochondrial content and function, orchestrating the expression of genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, fatty acid oxidation, and angiogenesis. The proliferation of healthy mitochondria enhances cellular energy production and improves metabolic flexibility, directly counteracting the energy deficits associated with hormonal dysregulation.

This metabolic reprogramming extends to glucose and lipid homeostasis. Exercise improves insulin sensitivity through multiple pathways, including increased expression and translocation of GLUT4 (Glucose Transporter Type 4) in muscle cells, enhanced insulin receptor signaling, and a reduction in circulating inflammatory cytokines that can induce insulin resistance. The chronic, low-grade inflammation often seen in sedentary individuals creates a systemic environment hostile to optimal hormone function; exercise actively dismantles this inflammatory milieu, fostering a more receptive state for endocrine signaling.

Neuroendocrine Axis Re-Patterning

The impact of exercise on the neuroendocrine axes is perhaps the most compelling evidence of its restorative power. The HPA axis, often hyperactive or blunted in sedentary individuals, undergoes significant re-patterning with consistent training. Chronic exercise enhances negative feedback sensitivity within the HPA axis, leading to a more regulated release of cortisol and improved stress adaptation. This involves alterations in receptor density and signaling pathways within the hypothalamus, pituitary, and adrenal glands, fostering a more resilient stress response system.

Regarding the HPG axis, the evidence points toward exercise-induced modulation of pulsatile GnRH (Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone) secretion from the hypothalamus, which subsequently influences LH (Luteinizing Hormone) and FSH (Follicle-Stimulating Hormone) release from the pituitary. In men, this can translate to enhanced Leydig cell function and testosterone biosynthesis.

In women, appropriate exercise intensity supports ovarian follicular development and steroidogenesis, contributing to more regular ovulatory cycles and balanced gonadal hormone production. The nuanced interplay between exercise intensity, energy availability, and HPG axis function remains an area of active investigation, highlighting the importance of personalized exercise prescriptions.

Furthermore, the growth hormone (GH) axis, critical for tissue repair, body composition, and metabolic health, is highly responsive to exercise. Acute bouts of intense exercise significantly elevate GH secretion, driven by neural and humoral factors. Chronic training can enhance the overall pulsatility and responsiveness of the somatotropic axis, leading to sustained benefits in lean mass maintenance and lipolysis.

The integration of therapeutic peptides like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295 can augment this endogenous GH release, acting as potent stimuli for the pituitary gland, thereby accelerating the body’s intrinsic regenerative capacities. This targeted biochemical recalibration works in concert with the systemic signals generated by physical activity, offering a comprehensive strategy for restoring youthful physiological function.

- Epigenetic Modifications ∞ Exercise influences DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications, altering gene expression related to metabolism and inflammation.

- Mitochondrial Health ∞ Regular activity promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and improves their functional efficiency, enhancing cellular energy production.

- Neurotransmitter Balance ∞ Physical exertion modulates neurotransmitter synthesis and receptor sensitivity, impacting mood and cognitive function.

The comprehensive reversal of hormonal damage from chronic sedentarism through exercise is a testament to the body’s remarkable adaptive capacity. It involves a sophisticated interplay of epigenetic, cellular, and neuroendocrine adjustments, guided by the precise stimuli of physical activity. The restoration is not a simple undoing but a profound recalibration, re-establishing a healthier, more dynamic physiological state.

References

- Boron, Walter F. and Emile L. Boulpaep. Medical Physiology. Elsevier, 2017.

- Guyton, Arthur C. and John E. Hall. Textbook of Medical Physiology. Elsevier, 2020.

- Kraemer, William J. and Nicholas A. Ratamess. “Hormonal Responses and Adaptations to Resistance Exercise and Training.” Sports Medicine, vol. 35, no. 4, 2005, pp. 339-361.

- Handschin, Christoph, and Bruce M. Spiegelman. “PGC-1alpha Orchestrates Metabolic Remodelling and Mitochondrial Biogenesis.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 17, no. 10, 2006, pp. 403-410.

- Chrousos, George P. “Stress and Disorders of the Stress System.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 5, no. 7, 2009, pp. 374-381.

- Vella, Laura K. and Michael I. L. Johnson. “Exercise and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis in Males.” Sports Medicine, vol. 44, no. 7, 2014, pp. 881-893.

- Hackney, Anthony C. et al. “The Exercise-Induced Growth Hormone Response ∞ An Overview.” Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, vol. 10, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1-7.

- Pedersen, Bente K. and Mark A. Febbraio. “Muscles, Exercise and Obesity ∞ Skeletal Muscle as a Secretory Organ.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 8, no. 3, 2012, pp. 157-165.

- Phillips, Stuart M. “The Science of Muscle Hypertrophy ∞ Making More Muscle with Exercise and Nutrition.” Clinical Nutrition, vol. 39, no. 11, 2020, pp. 3350-3356.

- Kelly, Benjamin, and G. William Wong. “The Role of Leptin in Human Physiology ∞ A Review.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 10, 2019, pp. 282.

Reflection on Your Path to Vitality

The knowledge presented here offers a framework for understanding the profound interplay between your lifestyle and your intrinsic biological rhythms. Recognizing the body’s capacity for adaptation and restoration through purposeful movement marks a significant step. Your personal health journey is a dynamic process, a continuous dialogue between your actions and your physiology.

This understanding provides the foundation; the next steps involve listening to your body’s unique signals and, when appropriate, seeking guidance to tailor these insights into a personalized wellness protocol. Reclaiming your vitality and optimal function is a journey of self-discovery, grounded in scientific principles and empowered by informed choices.