Fundamentals

The feeling often begins as a subtle shift, an undercurrent of change in the way your body and mind operate. It might be a persistent fatigue that sleep does not seem to remedy, a noticeable decline in your sense of vitality, or changes in your mood and cognitive clarity that feel disconnected from your daily life.

When you seek answers for these experiences, the conversation frequently turns to hormones, a topic that can feel both deeply personal and clinically complex. The possibility of using hormonal therapies, such as testosterone, can introduce a new layer of questions, particularly concerning long-term health and safety. The concern about breast cancer risk is valid and deserves a clear, thorough exploration grounded in the body’s own biological logic.

Your body is a cohesive system of communication. At the heart of this network is the endocrine system, which uses hormones as chemical messengers to coordinate countless functions, from your metabolic rate to your sleep-wake cycles. These messengers travel through the bloodstream, delivering instructions to specific cells that are equipped with the correct receptors to hear them.

Understanding this system is the first step toward understanding your own health. The conversation about testosterone in women must begin here, within the context of this intricate biological dialogue, to appreciate its role and influence.

The Symphony of Female Hormones

In the premenopausal years, a woman’s hormonal environment is characterized by a dynamic, cyclical interplay primarily orchestrated by the ovaries, pituitary gland, and hypothalamus ∞ an arrangement known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. While estrogen and progesterone are correctly identified as the principal conductors of the menstrual cycle and reproductive health, they are not solo performers.

Testosterone, an androgen, is a vital third member of this hormonal trio, produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands. Its presence in the female body is essential for maintaining a range of physiological functions.

Testosterone contributes significantly to:

- Musculoskeletal Health ∞ It aids in building and maintaining lean muscle mass and bone density.

- Cognitive Function ∞ The hormone supports mental clarity, focus, and mood stability.

- Libido and Sexual Response ∞ It is a key driver of sexual desire and satisfaction.

- Energy and Vitality ∞ Healthy testosterone levels are linked to a robust sense of energy and overall well-being.

A deficiency in this critical hormone can manifest as the very symptoms that prompt many women to seek medical guidance ∞ unexplained weight gain, persistent low energy, a decline in motivation, and a muted libido. These are not isolated issues; they are signals from the body indicating a disruption in its internal communication system.

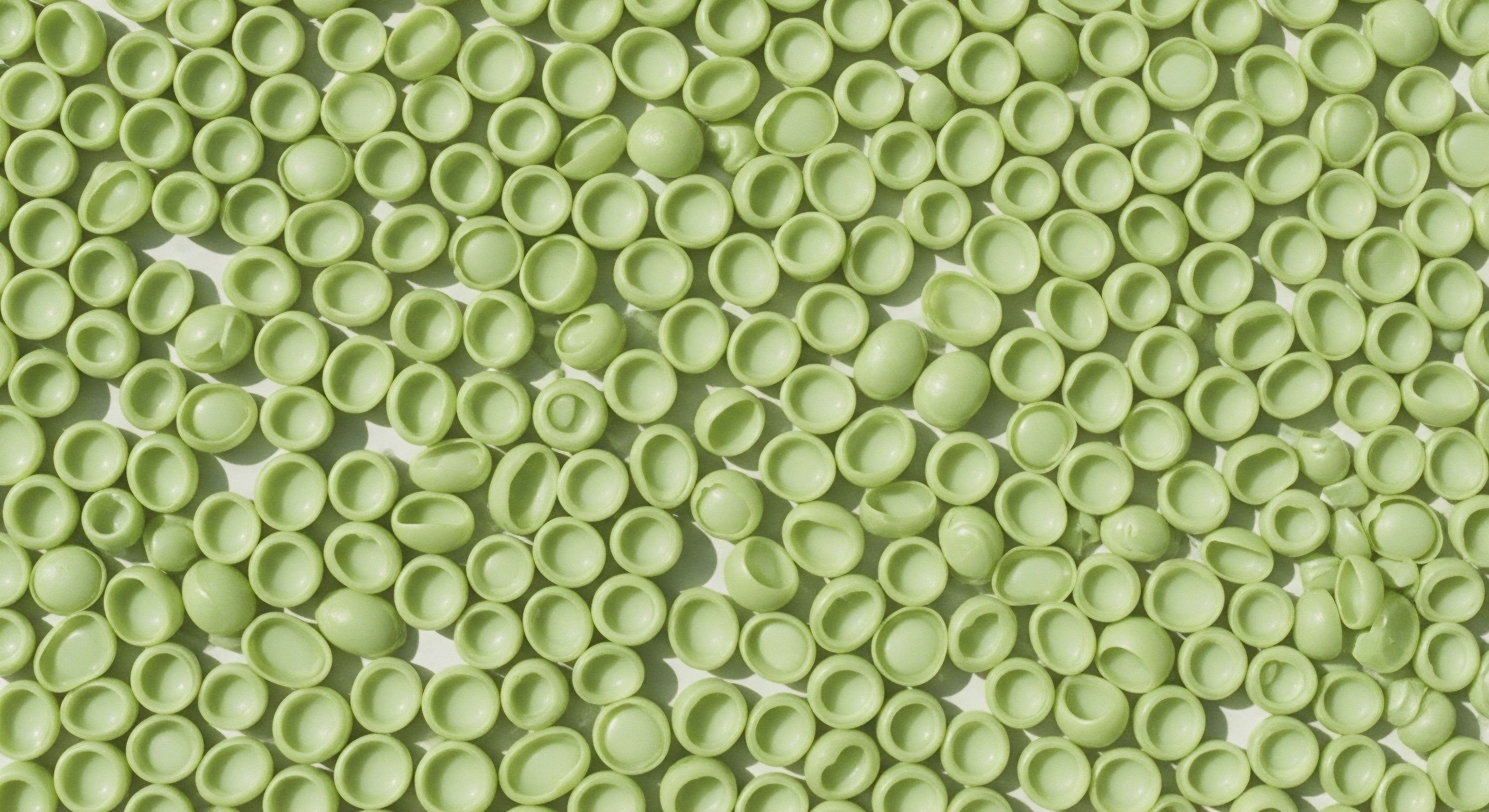

Hormones are the body’s chemical messengers, and their balance is fundamental to overall health and function.

How Hormones Interact with Breast Tissue

Breast tissue is highly responsive to hormonal signals. Cells within the breast are equipped with receptors for estrogen (ER), progesterone (PR), and androgens (AR). When a hormone binds to its corresponding receptor, it initiates a cascade of events inside the cell, instructing it to grow, divide, or perform a specific function.

The development of breast cancer is intimately linked to these signaling pathways. For decades, the primary focus has been on the role of estrogen, as its binding to the ER can stimulate cell proliferation, a necessary step for tumor growth in ER-positive cancers.

This understanding has logically led to questions about any hormonal intervention. If estrogen can promote the growth of certain cancers, what is the effect of administering testosterone? The answer requires a more detailed look at how testosterone itself functions within this complex environment. Testosterone does not act in isolation.

Its influence is determined by its direct actions on the androgen receptor and by its potential to be converted into other hormones, a process central to assessing its impact on breast health.

What Does It Mean to Be Premenopausal?

The term ‘premenopausal’ defines the span of a woman’s reproductive life from her first menstrual cycle until her final one. During this time, the HPG axis manages a rhythmic, monthly fluctuation of hormones to govern ovulation and menstruation. This period is one of hormonal vibrancy, but it is also a time when imbalances can occur.

Factors like chronic stress, poor nutrition, and environmental exposures can disrupt the delicate hormonal symphony, leading to symptoms long before the natural transition into perimenopause and menopause begins. When considering testosterone therapy, the premenopausal context is critical because the body’s baseline hormonal production and receptivity are different from those in postmenopausal women.

The exploration into testosterone therapy’s safety is therefore an exploration into balance. It examines what happens when a key messenger is supplemented to restore a more optimal physiological state. The central question becomes whether this restoration enhances the body’s protective mechanisms or introduces new risks. Answering this involves moving past simplistic assumptions and looking directly at the clinical evidence and the biological mechanisms at play.

Intermediate

For a premenopausal woman experiencing symptoms of hormonal imbalance, the decision to consider testosterone therapy is grounded in a desire to restore function and reclaim a sense of self. The protocol is not a matter of simply adding more of a single hormone; it is a precise clinical intervention designed to recalibrate a complex system.

Understanding the therapeutic rationale, the delivery methods, and the evidence surrounding its use is essential for a truly informed conversation about its potential effects on breast health.

The Clinical Rationale for Testosterone Therapy

Testosterone is prescribed for premenopausal women to address a constellation of symptoms linked to androgen insufficiency. While no single blood test can definitively diagnose a “deficiency” in the way it can for other conditions, a combination of symptomatic presentation and laboratory findings guides clinical judgment. A physician may recommend hormonal optimization protocols for women reporting:

- Persistent fatigue and lethargy

- Difficulty with concentration or “brain fog”

- Depressed mood or increased irritability

- A marked decrease in libido and sexual satisfaction

- Loss of muscle tone despite regular exercise

- Increased body fat, particularly around the abdomen

The therapeutic goal is to restore testosterone levels to a healthy physiological range, thereby alleviating these symptoms and improving quality of life. The approach is highly personalized, with dosages adjusted based on an individual’s response and ongoing lab monitoring.

Why Does the Delivery Method Matter?

The way a hormone is introduced into the body significantly affects its activity and safety profile. Oral forms of testosterone are generally avoided in women because they undergo a “first pass” through the liver, which can produce unfavorable metabolic byproducts and place strain on the organ. Instead, therapies are designed to mimic the body’s natural, steady release of hormones.

Common delivery methods include:

- Subcutaneous Injections ∞ Typically, small weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate (e.g. 0.1 ∞ 0.2ml) provide a stable level of the hormone in the bloodstream. This method avoids the liver’s first-pass metabolism and allows for precise, adjustable dosing.

- Subcutaneous Pellets ∞ These are small, rice-sized implants placed under the skin that release a consistent dose of testosterone over three to four months.

Pellet therapy is valued for its convenience and ability to maintain steady-state hormone levels, avoiding the peaks and troughs that can occur with other methods.

- Transdermal Creams ∞ Applied daily to the skin, these creams deliver testosterone directly into the circulation. Dosing can be less precise than with injections or pellets, and there is a risk of transference to others through skin contact.

The method of hormone delivery is a critical factor, as it directly influences how the body processes the hormone and its resulting biological effects.

Re-Examining the Link between Testosterone and Breast Cancer

The conventional thinking that all androgens increase breast cancer risk is being challenged by a growing body of clinical evidence. Several recent studies have investigated the incidence of breast cancer in women undergoing testosterone therapy, and their findings suggest a different relationship. The key appears to lie in the direct action of testosterone on the androgen receptor (AR) and its relationship with the estrogen receptor (ER).

A central process in this discussion is aromatization, the natural conversion of androgens (like testosterone) into estrogens by the enzyme aromatase. This pathway is a source of concern, as it could theoretically increase estrogen levels and stimulate ER-positive breast tissue. However, therapeutic protocols are often designed to manage this conversion. Sometimes, a medication like Anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, is co-administered to block this process, ensuring that the primary effects of the therapy are androgenic, not estrogenic.

The table below summarizes key findings from recent large-scale studies investigating the relationship between testosterone therapy and breast cancer incidence.

| Study and Year | Study Type | Key Findings on Breast Cancer Risk | Context and Patient Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donovitz & Cotten (2021) | 9-year retrospective study | A 35.5% reduction in invasive breast cancer incidence compared to expected rates.

The observed rate was 144 cases per 100,000 person-years, significantly lower than the general population. |

Included 2,377 pre- and post-menopausal women treated with subcutaneous testosterone pellets, some with concurrent estradiol. |

| Agrawal et al. (2024) | Large claims database analysis | Found a similar risk of malignant breast neoplasm in younger women (18-55) on TTh compared to controls (Relative Risk 0.62, but not statistically significant).

A significantly lower risk was found in women over 56. |

Compared thousands of women receiving testosterone therapy (TTh) to propensity-matched controls not on the therapy. |

These studies suggest that, far from increasing risk, testosterone therapy may have a neutral or even protective effect on breast tissue. The Donovitz & Cotten study, for instance, reported a substantial reduction in breast cancer incidence among women using testosterone pellets.

Even when estradiol was added to the regimen, the risk did not increase, challenging the idea that any estrogen exposure is inherently dangerous in this context. The Agrawal et al. database analysis corroborates this by finding no increased risk in premenopausal-aged women.

What Is the Biological Mechanism for This Protective Effect?

The emerging understanding is that testosterone’s primary action through the androgen receptor may directly counteract estrogen-driven proliferation in breast tissue. When testosterone binds to the AR on breast cells, it can trigger a cascade of anti-proliferative signals.

It may induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) in cancerous cells and downregulate the expression of the estrogen receptor, effectively making the tissue less sensitive to estrogen’s growth signals. This creates a biological system where the androgenic effects of testosterone provide a counterbalance to the proliferative effects of estrogen. The result is a more regulated environment where cellular growth is kept in check. The therapeutic use of testosterone, particularly when aromatization is managed, appears to leverage this natural, protective mechanism.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the relationship between testosterone and breast cancer risk in premenopausal women requires moving beyond population-level data into the realm of cellular biology and endocrinological signaling.

A central paradox complicates the clinical narrative ∞ while some prospective studies show that higher levels of endogenous (naturally produced) testosterone are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, several clinical studies on exogenous (therapeutically administered) testosterone report a neutral or reduced risk. Resolving this apparent contradiction lies in understanding the nuanced, context-dependent actions of androgens within the microenvironment of breast tissue.

The Androgen Receptor as a Tumor Suppressor

The androgen receptor (AR) is expressed in approximately 70-90% of invasive breast cancers, including a majority of estrogen receptor-positive (ER-positive) tumors. For many years, its role was overlooked, but contemporary research has positioned the AR as a significant modulator of breast cancer biology. In ER-positive breast cancer cells, the activation of the AR by androgens like testosterone can exert a powerful anti-proliferative effect. This occurs through several distinct molecular mechanisms:

- Direct Genomic Signaling ∞ When testosterone or its more potent metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), binds to the AR, the complex translocates to the nucleus. There, it binds to specific DNA sequences known as androgen response elements (AREs) located near genes that regulate cell growth. This binding can directly inhibit the transcription of genes that promote cell cycle progression, effectively putting a brake on cell division.

- Crosstalk with ER Signaling ∞ AR activation interferes directly with ER signaling pathways. The AR can compete with the ER for binding to shared transcriptional co-regulators, which are proteins necessary for the ER to initiate its pro-growth genetic program. By sequestering these essential co-regulators, the AR effectively dampens the cell’s response to estrogen.

- Downregulation of ER Expression ∞ Sustained androgen signaling has been shown to decrease the expression of the ER gene (ESR1) itself. This reduces the number of estrogen receptors on the cell surface, making the cell fundamentally less sensitive to the proliferative signals of estradiol.

This evidence provides a strong mechanistic rationale for the findings in the Donovitz & Cotten study. The continuous, steady-state delivery of testosterone via subcutaneous pellets likely maintains sufficient AR activation to exert these anti-proliferative, ER-antagonistic effects, leading to a net reduction in breast cancer incidence.

The activation of the androgen receptor in breast tissue can initiate a cascade of anti-proliferative signals that directly counteract estrogen-driven cellular growth.

Resolving the Endogenous Vs Exogenous Paradox

Why would high endogenous testosterone be linked to increased risk, while exogenous testosterone therapy appears protective? The answer likely involves the metabolic fate of testosterone and the overall hormonal milieu. In premenopausal women, endogenous testosterone exists in a complex equilibrium with a host of other hormones.

High testosterone in this context is often a marker of broader endocrine dysregulation, such as that seen in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), which is itself an independent risk factor for certain cancers. It may signal a state of elevated insulin, inflammation, and, crucially, higher rates of peripheral aromatization of androgens into potent estrogens without the counterbalancing effects of adequate progesterone.

The table below outlines the key distinctions between the physiological state associated with high endogenous testosterone and the state created by properly managed exogenous therapy.

| Factor | High Endogenous Testosterone (as a risk marker) | Exogenous Testosterone Therapy (as a clinical intervention) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Often a marker of underlying metabolic dysfunction (e.g.

insulin resistance) and increased aromatization to estradiol. The risk is driven by the resulting high estrogen-to-androgen ratio. |

Direct activation of the AR pathway, which has anti-proliferative effects. Aromatization is often controlled, leading to a favorable androgen-to-estrogen ratio. |

| Hormonal Context | Frequently associated with elevated estrogens, insulin, and inflammatory cytokines, alongside potential progesterone deficiency. | Administered to achieve a specific physiological level.

Often combined with progesterone in premenopausal protocols and may include an aromatase inhibitor to limit estrogen conversion. |

| Receptor Effect | The net effect is often dominated by ER-driven proliferation due to high levels of aromatized estrogen. | The net effect is dominated by AR-driven growth inhibition and apoptosis, which counteracts baseline ER signaling. |

What Are the Unanswered Questions in Research?

While the current evidence is compelling, further research is needed to fully elucidate the role of testosterone in breast health. Most large-scale studies, like the one by Donovitz & Cotten, are retrospective and focus on specific delivery methods like pellets. Prospective, randomized controlled trials are the gold standard and are needed to confirm these findings definitively.

Furthermore, research must continue to explore the differential effects of androgens in various breast cancer subtypes. For example, the role of the AR in ER-negative and triple-negative breast cancer is an area of active investigation and appears to be more complex. The future of hormonal optimization will involve an even more personalized approach, potentially using genetic markers to predict an individual’s response to therapy and their inherent risk profile.

The current body of evidence, however, supports a significant re-evaluation of testosterone’s role in female health. The data suggests that, when administered correctly within a therapeutic framework, testosterone functions as a balancing hormone, leveraging the AR signaling pathway to confer a protective effect on breast tissue. This represents a critical shift in the clinical understanding, moving from a position of broad caution to one of nuanced, evidence-based application.

References

- Donovitz, G. & Cotten, M. (2021). Breast Cancer Incidence Reduction in Women Treated with Subcutaneous Testosterone ∞ Testosterone Therapy and Breast Cancer Incidence Study. European Journal of Breast Health, 17(2), 150 ∞ 156.

- LowTE Florida. (2024). Testosterone Therapy and Breast Cancer Incidence Study ∞ An Overview. Retrieved from LowTE Florida website.

- Agrawal, P. Singh, S. M. Hsueh, J. Grutman, A. An, C. Able, C. Choi, U. Kohn, J. Clifton, M. & Kohn, T. P. (2024). Testosterone therapy in females is not associated with increased cardiovascular or breast cancer risk ∞ a claims database analysis. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 21(3), 209-217.

- Kaaks, R. Tikk, K. Sookthai, D. Schock, H. Johnson, T. Grote, V. A. & Dossus, L. (2014). Premenopausal serum androgens and breast cancer risk ∞ a nested case-control study. Breast Cancer Research, 16(2), R31.

- Gounder, C. (2025, July 2). Study finds link between certain types of hormone therapy and higher rates of breast cancer. CBS Mornings.

- Glaser, R. L. & Dimitrakakis, C. (2013). Testosterone and breast cancer prevention. Maturitas, 76(4), 308-315.

- Hickey, T. E. Robinson, J. L. & Tilley, W. D. (2012). Androgen receptor in breast cancer ∞ a complex and controversial relationship. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, 19(3), 223-231.

- Somboonporn, W. & Davis, S. R. (2004). Testosterone and its role in the female. Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs, 5(10), 1046-1052.

Reflection

Your Personal Health Blueprint

The information presented here offers a detailed map of the current scientific and clinical landscape surrounding testosterone therapy and breast health. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It transforms abstract concerns into a structured understanding of your body’s intricate biology. It allows you to move from a place of uncertainty to one of informed inquiry.

Your personal health journey is unique, defined by your genetics, your history, and your specific experiences. The symptoms you feel are real data points, signals from a system seeking equilibrium.

Consider this exploration as the beginning of a new chapter in your relationship with your own body. The path to optimal function is one of partnership ∞ between you and a knowledgeable clinical guide who respects your lived experience and can translate the complexities of endocrinology into a personalized protocol.

The ultimate goal is to restore the body’s own intelligent design, allowing you to function with vitality and clarity. What you have learned here is the foundation upon which you can build those constructive, life-altering conversations.