Fundamentals

You may be considering hormonal therapy and find yourself asking about its influence on cardiovascular health. This is a perceptive and critical question. Your body is an intricate network of systems, and understanding how they interact is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

The experience of hormonal change is deeply personal, and the symptoms you feel are valuable data points, signaling a shift in your internal environment. Let’s translate those signals by examining the foundational relationship between testosterone and blood pressure.

The Body’s Internal Messenger

Testosterone is a primary steroid hormone, a powerful chemical messenger that communicates with cells throughout your body. While it is produced in much larger quantities in men, it is also essential for women, contributing to bone density, muscle mass, and metabolic function in both sexes. Its role extends far beyond reproduction.

Think of it as a master regulator, influencing everything from energy levels to the health of your circulatory system. The circulatory system itself, a vast network of blood vessels with the heart at its center, is what maintains blood pressure. Blood pressure is the physical force exerted by circulating blood upon the walls of your arteries.

A Tale of Two Signals

When testosterone levels are altered through therapeutic protocols, the hormone can send two distinct and opposing signals to the cardiovascular system. The net effect on an individual’s blood pressure depends on which of these signals resonates more strongly within their unique physiology.

The first signal involves the production of red blood cells, a process called erythropoiesis. Testosterone can stimulate the bone marrow to create more of these cells. A higher concentration of red blood cells in the blood, measured as hematocrit, increases the blood’s viscosity, or thickness. A thicker fluid requires more force from the heart to pump it through the vascular network, which can lead to an increase in blood pressure. This is a direct, mechanical relationship.

The body’s response to testosterone involves a delicate interplay between mechanisms that can either increase or decrease vascular pressure.

The second signal is one of relaxation. Testosterone can influence the inner lining of blood vessels, the endothelium, to produce more nitric oxide. Nitric oxide is a potent vasodilator, meaning it causes the smooth muscles of the arteries to relax and widen.

This widening of the vessels creates more space for blood to flow, thereby reducing the pressure against the artery walls. This action is a key component of cardiovascular health and demonstrates testosterone’s protective potential. The final impact on your blood pressure is a result of the balance between these two powerful, competing biological actions.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the basic mechanics, the clinical reality of hormonal optimization reveals significant differences in how male and female bodies process and respond to testosterone. These differences are rooted in baseline physiology, the specific goals of therapy, and the synergistic effects of other hormones. The protocols for men and women are designed with these distinctions in mind, and so is the approach to monitoring cardiovascular wellness.

The Male Protocol and Cardiovascular Monitoring

For men undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), the objective is typically to restore circulating testosterone to the optimal range of a healthy young adult. A common protocol involves weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate, often paired with ancillary medications like Gonadorelin to maintain testicular function and Anastrozole to manage estrogen conversion.

Monitoring blood pressure is a standard and necessary part of this process. The therapeutic dose that restores energy and cognitive function also activates the physiological mechanisms we’ve discussed. An increase in hematocrit is a common and expected outcome of successful TRT. Therefore, clinicians watch this value closely alongside blood pressure readings to ensure the benefits of therapy are achieved without introducing undue cardiovascular strain.

| Cardiovascular Marker | State of Low Testosterone (Hypogonadism) | State of Optimized Testosterone (TRT) |

|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Function |

Often impaired, leading to reduced vasodilation. |

Generally improved due to increased nitric oxide availability. |

| Blood Viscosity (Hematocrit) |

Within the lower end of the normal range. |

Increases, potentially elevating blood pressure if not monitored. |

| Inflammation |

Systemic inflammation markers are often elevated. |

Can be reduced, contributing to better vascular health. |

| Sodium Retention |

Generally stable. |

May slightly increase, requiring attention to hydration and diet. |

The Female Protocol and Hormonal Synergy

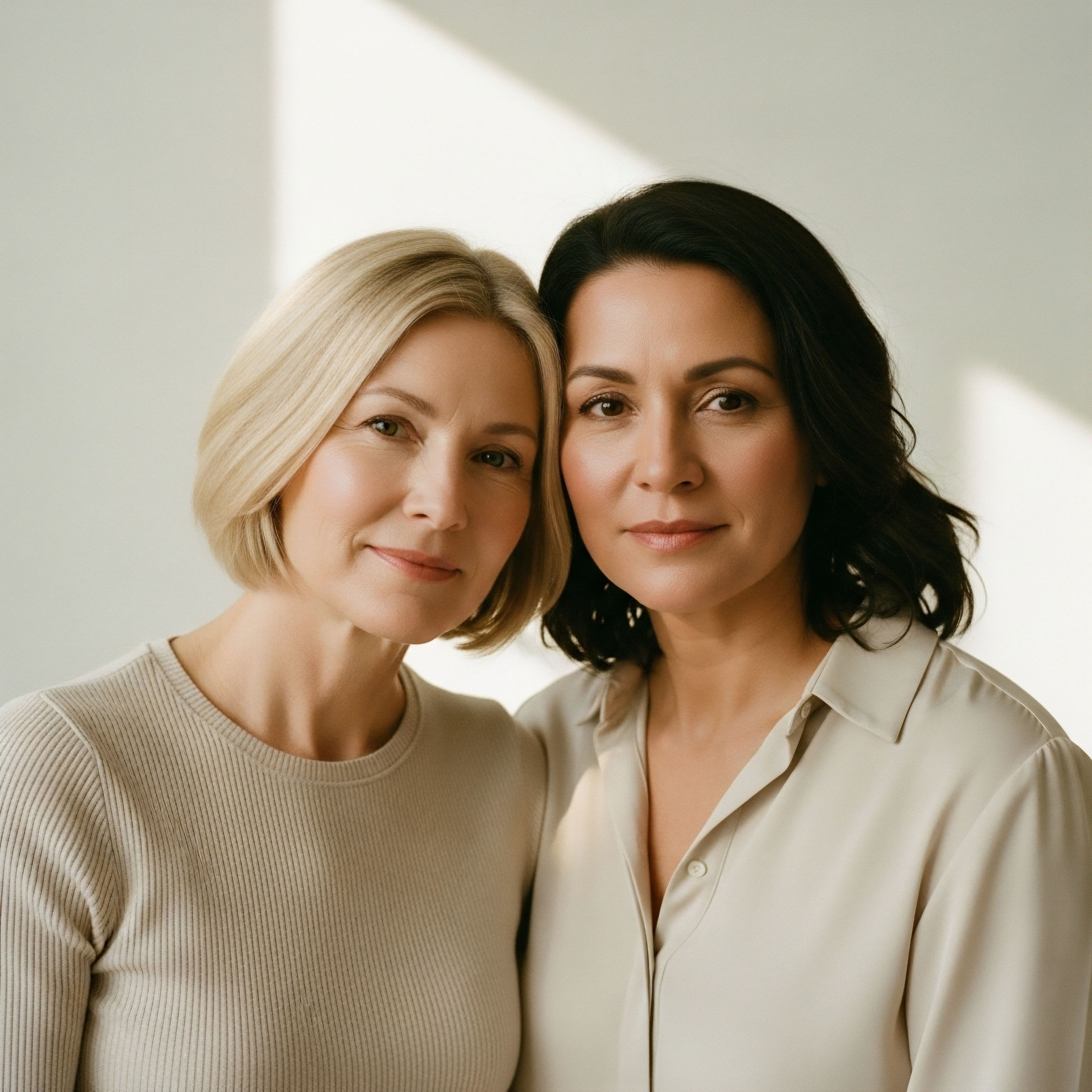

For women, hormonal therapy is a different paradigm. The goal is re-establishing balance within a complex hormonal symphony, especially during the perimenopausal and postmenopausal transitions. Testosterone is used in much smaller doses, often subcutaneously, and is almost always considered in relation to estrogen and progesterone levels.

The critical factor for women is the androgen-to-estrogen ratio. Before menopause, abundant estrogen provides significant cardiovascular protection, promoting vasodilation and maintaining vascular health. After menopause, estrogen levels plummet. This creates a new internal environment where the biological effects of androgens, including testosterone, become more pronounced. Even a low, therapeutic dose of testosterone can have a different impact in a low-estrogen state.

In women, the cardiovascular effect of testosterone therapy is inseparable from the concurrent status of estrogen and progesterone.

The physiological response to testosterone in women is shaped by several unique factors:

- Baseline Hormonal Status ∞ A postmenopausal woman with very low estrogen will have a different vascular response to testosterone than a perimenopausal woman who still has fluctuating estrogen levels.

- Progesterone’s Role ∞ The inclusion of progesterone in a woman’s protocol is significant. Progesterone has its own effects on the vascular system, which can be calming and may help balance the effects of testosterone.

- Dosage Sensitivity ∞ Female physiology is calibrated to respond to much lower levels of testosterone. Therefore, precision in dosing is paramount to avoid shifting the delicate hormonal balance in an unfavorable direction.

- Aromatization ∞ The conversion of testosterone to estradiol (a form of estrogen) occurs in women as well as men. In some postmenopausal women, this conversion can be beneficial, providing a small amount of needed estrogen. This process underscores the interconnectedness of these hormones.

What Is the Clinical Approach to Managing These Differences?

A personalized clinical protocol anticipates these sex-specific responses. For a man on TRT, the focus might be on managing hematocrit through blood donation or dose adjustment. For a woman, the strategy involves carefully balancing testosterone with estrogen and progesterone to recreate a healthy physiological state, with blood pressure as a key indicator of that balance. This validates the necessity of individualized medicine over one-size-fits-all approaches.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of testosterone’s effect on blood pressure requires moving beyond systemic effects and into the cellular and molecular signaling pathways. The divergent outcomes observed between men and women are not arbitrary; they are the result of sex-specific differences in receptor sensitivity, enzymatic activity, and the background hormonal milieu that modulates androgenic action. The ultimate effect on vascular tone is a complex summation of genomic and non-genomic actions interacting with other regulatory systems.

Genomic versus Non-Genomic Actions on the Vasculature

Testosterone exerts its influence through two primary modes of action. The classical, or genomic, pathway involves the hormone binding to intracellular androgen receptors, which then travel to the cell nucleus to alter gene expression. This is a relatively slow process, taking hours to days, and it is the pathway responsible for stimulating the production of red blood cells in the bone marrow.

The non-genomic pathway is rapid, occurring within seconds to minutes. It involves testosterone interacting with receptors on the cell membrane, triggering immediate changes in intracellular signaling cascades. A key non-genomic effect is the activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the enzyme that produces the vasodilator nitric oxide. The capacity for this rapid vasodilation is a crucial protective mechanism, and its efficiency can vary between sexes and with age.

Interaction with the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System

The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) is a cornerstone of blood pressure regulation. It is a hormonal cascade that ultimately leads to vasoconstriction and the retention of sodium and water by the kidneys, both of which increase blood pressure. Androgens are known to stimulate components of the RAAS.

They can increase the production of angiotensinogen from the liver, the precursor molecule for the entire cascade. This pressor effect of the RAAS stands in direct opposition to the vasodilatory effect of the non-genomic nitric oxide pathway.

The ultimate blood pressure outcome in any individual receiving testosterone therapy can be conceptualized as the equilibrium point between RAAS activation and eNOS-mediated vasodilation. In men with healthy endothelial function, the vasodilatory effect often counteracts the RAAS stimulation. In individuals with pre-existing endothelial dysfunction or in the low-estrogen state of post-menopause, the balance may tip in favor of the RAAS, resulting in a net increase in blood pressure.

The final determinant of testosterone’s vascular impact is the balance between its stimulation of the RAAS and its capacity for nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation.

Why Do Sex-Specific Differences in Blood Pressure Response Persist?

The differential response is multifactorial, grounded in the distinct endocrine environments of men and women. In men, higher baseline testosterone levels and vascular conditioning mean that restoring the hormone to an optimal range often enhances an already present vasodilatory capacity. For postmenopausal women, the equation is profoundly altered by the loss of estrogen.

Estrogen is a powerful modulator of both the RAAS and eNOS activity, generally promoting vasodilation and suppressing the RAAS. When estrogen is absent, the vascular system loses this protective influence. Introducing testosterone, even at low doses, into this environment means its effects on the RAAS are less effectively opposed.

| Mechanism | Predominant Effect in Men (Optimized Levels) | Predominant Effect in Postmenopausal Women |

|---|---|---|

| Nitric Oxide (eNOS) Activation |

Strong and rapid vasodilatory effect, a primary protective pathway. |

Present, but potentially blunted due to the loss of estrogen’s synergistic effects. |

| RAAS Stimulation |

Effect is present but often balanced by strong vasodilation. |

Effect may become more prominent due to the absence of estrogen’s opposing influence. |

| Erythropoiesis (Hematocrit) |

Significant increase, a primary mechanism for potential blood pressure elevation that requires clinical monitoring. |

Minimal to mild increase due to much lower therapeutic doses. |

| Aromatization to Estradiol |

An important pathway that contributes to vascular health; managed with inhibitors like Anastrozole if excessive. |

Can provide a small, potentially beneficial amount of estradiol in a low-estrogen environment. |

This evidence clarifies that testosterone therapy does not have a single, universal effect on blood pressure. The outcome is context-dependent, shaped by sex, baseline hormonal status, and the health of the underlying vascular and renal systems. This understanding forms the basis of safe and effective personalized hormone optimization.

References

- Traish, A. M. “Testosterone and cardiovascular disease ∞ an old idea with modern clinical implications.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 102, no. 11, 2017, pp. 3995-3997.

- Jones, T. H. et al. “Testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men with type 2 diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome (the TIMES2 study).” Diabetes Care, vol. 34, no. 4, 2011, pp. 828-837.

- Wang, J. et al. “The potential role of testosterone in hypertension and target organ damage in hypertensive postmenopausal women.” Journal of Clinical Hypertension, vol. 20, no. 10, 2018, pp. 1438-1445.

- Borst, S. E. & Shupe, E. U. “The role of testosterone in the management of obesity.” Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, vol. 22, no. 3, 2015, pp. 196-202.

- Guyton, A.C. & Hall, J.E. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th ed. Elsevier, 2016.

- Vlachopoulos, C. et al. “Effect of testosterone on endothelial function in men with coronary artery disease.” Vascular Medicine, vol. 14, no. 2, 2009, pp. 111-117.

- Moreau, K. L. et al. “Testosterone treatment in older men is associated with increased circulating endothelial progenitor cells.” American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, vol. 301, no. 5, 2011, pp. H2048-H2055.

Reflection

You began this inquiry with a specific question about testosterone and blood pressure. The answer, you now see, is not a simple yes or no. It is a dynamic process rooted in your individual biology. The information presented here is designed to be a bridge, connecting the symptoms you experience to the complex systems operating within you.

This knowledge transforms you from a passive recipient of care into an active, informed partner in your own health protocol. Your body communicates constantly. The true goal is to learn its language, to understand its signals, and to work with a clinical guide who can help you interpret the message and recalibrate the system for optimal function and vitality. What is your body telling you right now?