Fundamentals

The experience often begins subtly. It might be a word that rests just on the tip of your tongue, a key you’ve momentarily misplaced, or a thread of conversation that seems to fray and drift away. These moments, initially dismissed as products of stress or a poor night’s sleep, can accumulate, creating a quiet undercurrent of concern.

You might notice a certain sharpness has dulled, that the fluid recall of facts and figures now requires more deliberate effort. This feeling, this lived experience of a change in your own cognitive landscape, is the starting point for a deeper inquiry into your own biology. It is a valid and important signal from your body that its internal environment is shifting. Understanding this shift is the first step toward reclaiming your full cognitive vitality.

The body operates as an integrated system, a complex network of communication where hormones act as the primary messengers. Among the most significant of these messengers in the male body is testosterone. Its role extends far beyond the commonly understood domains of muscle mass, libido, and energy.

Testosterone is a profoundly influential molecule within the central nervous system. The brain is rich with androgen receptors, docking stations specifically designed to receive testosterone’s signals. When this hormone binds to these receptors, it initiates a cascade of biochemical events that directly support the health and function of brain cells, or neurons. This interaction is fundamental to maintaining the very structure and operational integrity of the cognitive machinery.

The Brain’s Command and Control System

To appreciate how hormonal balance influences cognition, we must first look at the body’s master regulatory circuit ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This is an elegant, self-regulating feedback loop that governs the production of testosterone. The process begins in the hypothalamus, a small but powerful region in the brain, which releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH).

This signal travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, prompting it to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) into the bloodstream. LH then travels to the Leydig cells in the testes, instructing them to produce testosterone. As testosterone levels in the blood rise, they send a feedback signal back to both the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, telling them to slow down the release of GnRH and LH. This creates a stable, balanced hormonal environment.

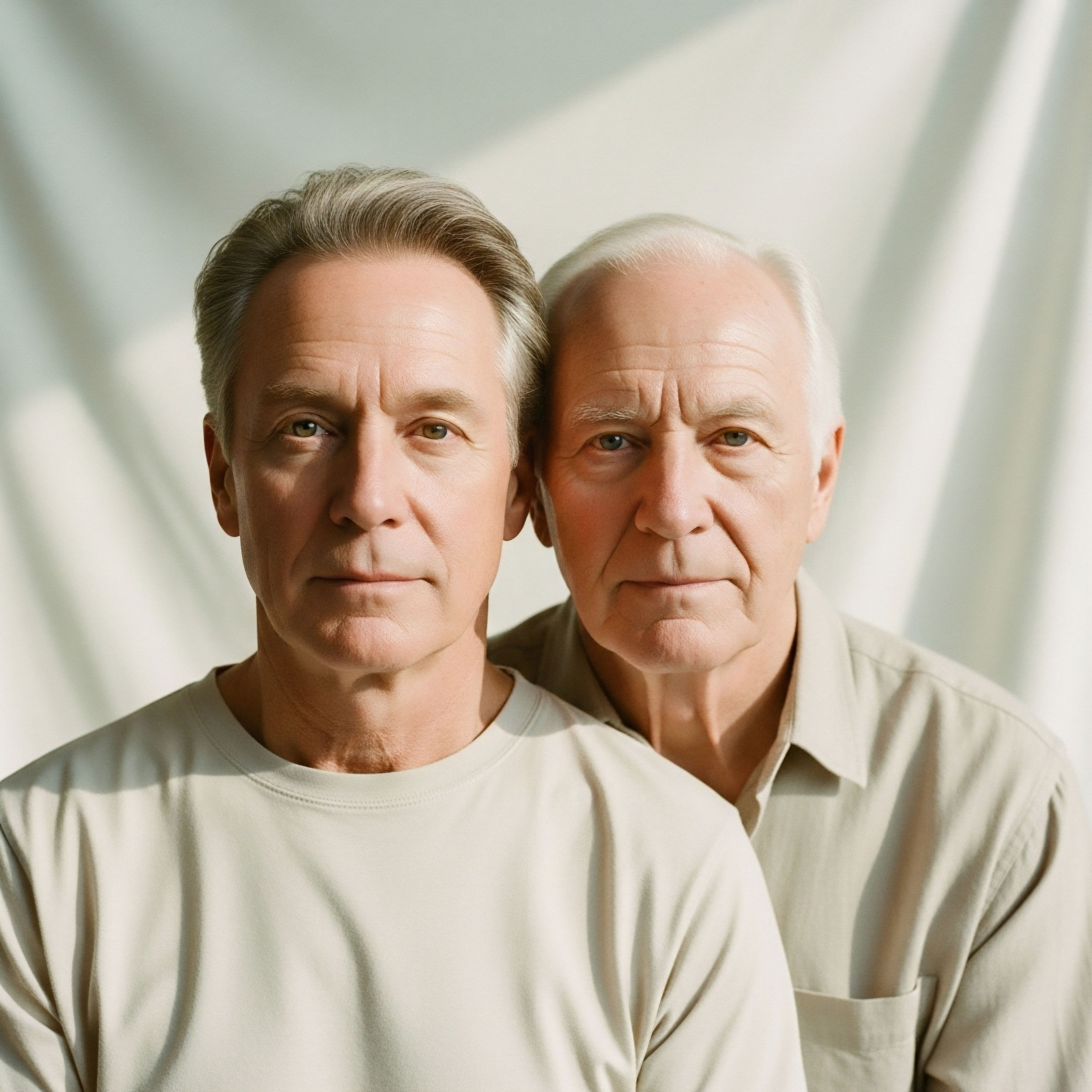

With age, the efficiency of this axis can decline. The signals may become weaker, or the testes may become less responsive. The result is a gradual reduction in circulating testosterone, a condition known as age-related hypogonadism. This decline disrupts the delicate biochemical equilibrium that the brain has relied upon for decades.

The consequences of this disruption are systemic, affecting mood, energy, and metabolic health, but its impact on cognitive function is particularly significant because the brain is so densely populated with the machinery to interact with this specific hormone. The feeling of mental fog or slowed processing is a direct reflection of this altered internal state.

The gradual decline in testosterone disrupts the brain’s established chemical environment, impacting the efficiency of neural communication.

Testosterone’s Role in Neural Architecture

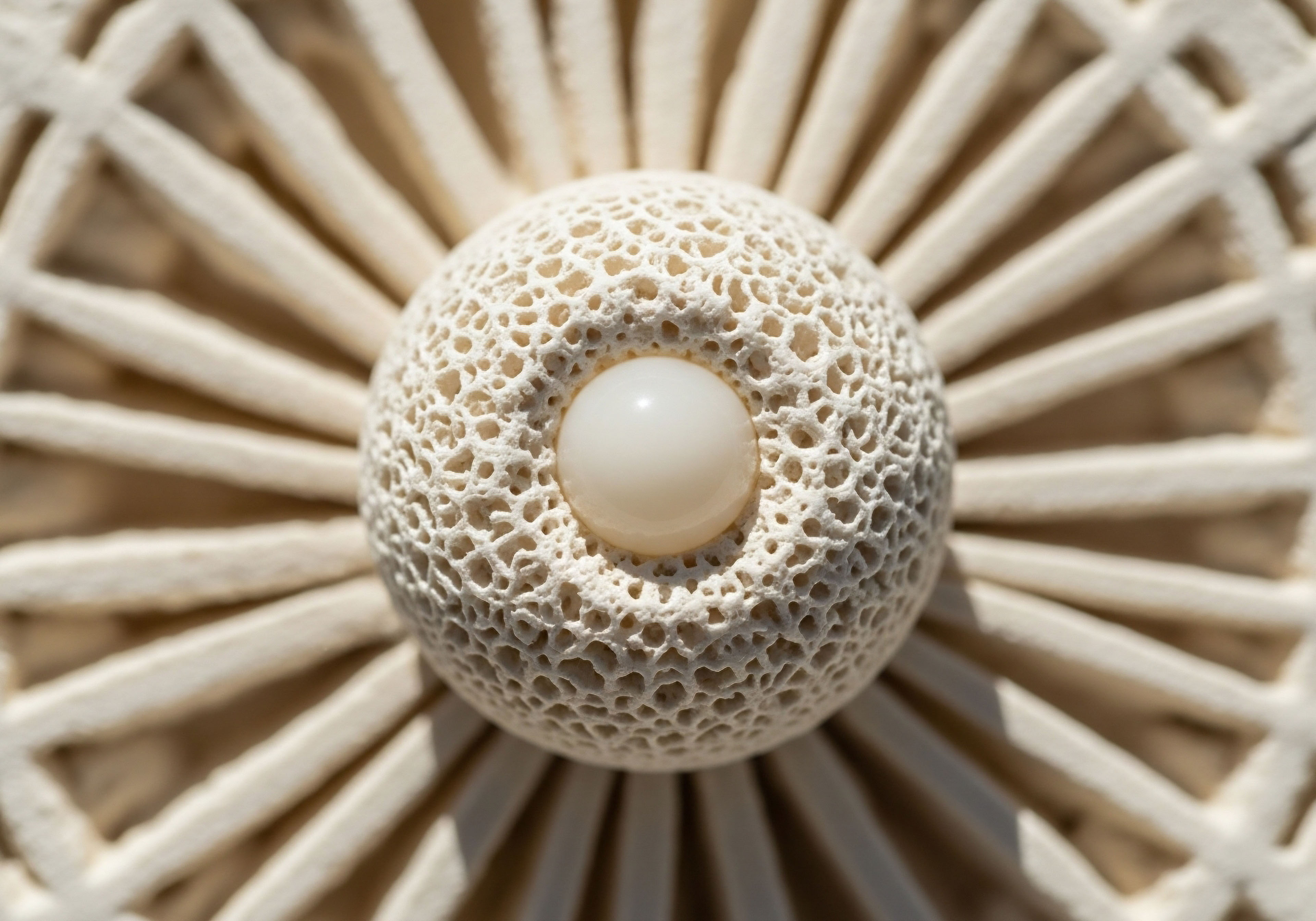

Cognition, at its most basic level, is the product of connections. The ability to learn, remember, and reason depends on the health and plasticity of synapses, the junctions where neurons communicate with one another. Testosterone plays a direct role in maintaining this synaptic architecture.

It promotes the growth of dendrites, the branch-like extensions of neurons that receive signals, and supports the density of dendritic spines, the tiny protrusions where synaptic connections are made. A brain with robust synaptic density is a brain that can form and retrieve memories efficiently, process information quickly, and adapt to new challenges.

Furthermore, testosterone has a profound neuroprotective effect. It helps shield neurons from various forms of cellular stress, including oxidative damage and inflammation, both of which are known contributors to age-related cognitive decline. It appears to modulate the production of key proteins, such as Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), which acts like a fertilizer for brain cells, encouraging their growth, survival, and differentiation.

When testosterone levels decline, this protective shield weakens, and the growth-promoting signals diminish. Neurons may become more vulnerable to damage, and the brain’s ability to repair itself and form new connections, a process called neuroplasticity, is compromised. This biological reality underlies the subjective experience of cognitive aging. It is a structural and functional change, one that can be understood and, potentially, addressed through a systems-based approach to health.

What Is the True Definition of Cognitive Decline?

Cognitive decline is a term that encompasses a spectrum of experiences. It is a gradual reduction in cognitive abilities, such as memory, attention, processing speed, and executive function, which includes planning and problem-solving. It is a normal part of the aging process for many, yet the rate and severity of this decline vary immensely among individuals.

The biological underpinnings involve a combination of factors ∞ a reduction in the number of neurons, a decrease in the integrity of the connections between them, and an increase in systemic inflammation that affects the brain.

From a functional perspective, it manifests as difficulty with tasks that were once effortless. It might be the challenge of multitasking, the struggle to follow a complex plot in a movie, or the increased reliance on notes and reminders to manage daily responsibilities.

These are not failures of character or intellect; they are symptoms of a changing neurobiological landscape. Recognizing them as such is empowering, as it shifts the focus from a sense of personal failing to a question of biological support.

The core question then becomes ∞ what can be done to restore the environment in which these brain cells operate, to provide them with the resources they need to function optimally? This is the foundational query that leads us to explore the potential of hormonal recalibration as a strategy for preserving cognitive resilience throughout the lifespan.

Intermediate

The decision to consider testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) marks a transition from understanding the “what” of hormonal decline to exploring the “how” of clinical intervention. For the man experiencing the tangible effects of low testosterone on his cognitive function, the question is deeply personal.

It centers on whether a carefully managed protocol can help restore the mental clarity and sharpness he feels he has lost. The clinical evidence presents a complex picture; some studies show measurable benefits, particularly in men who already exhibit mild cognitive impairment, while others report more modest or domain-specific results. This variability underscores a critical point ∞ TRT is a precise medical intervention, and its success depends entirely on a protocol tailored to the individual’s unique physiology.

A properly constructed hormonal optimization protocol seeks to re-establish a physiological state of balance. It involves more than simply administering testosterone. A comprehensive approach addresses the entire Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis to ensure the entire system is supported.

This is why standard protocols for men often include not just Testosterone Cypionate, but also ancillary medications like Gonadorelin and Anastrozole. Each component has a specific role designed to mimic the body’s natural hormonal symphony, optimizing benefits while mitigating potential side effects. Understanding the function of each element is key to appreciating how these therapies work to support systemic health, which in turn creates a more favorable environment for cognitive function.

A successful therapeutic outcome hinges on a comprehensive protocol that supports the entire endocrine axis, not just the target hormone level.

Dissecting a Modern TRT Protocol

A typical, well-managed protocol for male hormone optimization is a multi-faceted strategy. Its goal is to restore testosterone to a healthy physiological range while maintaining the function of related systems. Here is a breakdown of the core components and their clinical rationale:

- Testosterone Cypionate ∞ This is a bioidentical, long-acting ester of testosterone that forms the foundation of the therapy. Administered typically as a weekly intramuscular or subcutaneous injection, it provides a steady, stable level of testosterone in the bloodstream, avoiding the peaks and troughs that can come with other delivery methods. This stability is important for consistent signaling to the androgen receptors in the brain and body.

- Gonadorelin ∞ When the body receives testosterone from an external source, the HPG axis feedback loop can cause the pituitary gland to reduce its output of Luteinizing Hormone (LH). This can lead to a shutdown of the testes’ own natural testosterone production and a reduction in testicular size. Gonadorelin, a synthetic form of GnRH, is used to prevent this. By providing a periodic pulse of this signaling hormone, it stimulates the pituitary to continue releasing LH, thereby keeping the testes functional. This is important for maintaining fertility and a more complete hormonal profile.

- Anastrozole ∞ Testosterone can be converted into estrogen in the body through a process called aromatization. While some estrogen is necessary for male health, excessive levels can lead to side effects like water retention, gynecomastia, and mood changes. Anastrozole is an aromatase inhibitor, a medication that blocks this conversion process. It is used judiciously, typically in small oral doses, to keep estrogen levels within an optimal range, ensuring that the benefits of testosterone are maximized without creating a new hormonal imbalance.

- Enclomiphene ∞ In some protocols, Enclomiphene may be included. This compound works by selectively blocking estrogen receptors at the pituitary gland. By preventing estrogen from signaling the pituitary to slow down, it can help maintain or even increase the natural production of LH and FSH, further supporting testicular function and endogenous testosterone production.

This comprehensive approach ensures that the therapy is working with the body’s natural systems, aiming for a holistic recalibration rather than just a simple replacement of a single hormone. This systemic balance is what provides the foundation for potential cognitive benefits.

Mechanisms of Cognitive Enhancement

How does restoring testosterone translate into better brain function? The mechanisms are both direct and indirect, influencing the brain’s structure, chemistry, and overall health. The evidence from clinical trials has been mixed, with some meta-analyses finding no significant overall improvement, while others suggest benefits in specific cognitive domains like verbal memory or for specific populations, such as those with pre-existing cognitive deficits. This suggests the effects are nuanced and depend on the individual’s baseline condition.

The direct effects occur at the cellular level within the brain. Testosterone interacts with androgen receptors to promote synaptic plasticity, the brain’s ability to form and reorganize synaptic connections. This process is the physical basis of learning and memory.

Animal studies have shown that testosterone can increase the density of dendritic spines in the hippocampus, a brain region critical for memory formation. It also stimulates the production of vital neurotrophic factors like BDNF, which supports the survival and growth of neurons.

The indirect effects are just as important and relate to testosterone’s role in overall metabolic and vascular health. Low testosterone is frequently associated with insulin resistance, obesity, and systemic inflammation, all of which are independent risk factors for cognitive decline. By improving insulin sensitivity, promoting lean muscle mass, and reducing inflammatory markers, TRT can improve the brain’s metabolic environment.

A brain that is well-supplied with glucose and free from the damaging effects of chronic inflammation is a brain that can function more efficiently. Some research indicates that combining TRT with lifestyle interventions, such as exercise and diet, yields the most significant cognitive improvements, highlighting the importance of this systemic approach.

How Are Different Cognitive Domains Affected?

Cognitive function is not a single entity. It is a collection of distinct abilities, and testosterone appears to influence some of these domains more than others. The inconsistency in clinical trial results may be partly due to the wide variety of tests used to assess cognition. However, some patterns have emerged from the research.

The table below outlines several key cognitive domains and summarizes the general findings from research on testosterone therapy. It is important to view this as a general guide, as individual responses can vary significantly.

| Cognitive Domain | Description | Observed Effects of Testosterone Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Verbal Memory | The ability to recall words, lists, and stories. | Some studies report improvements, suggesting testosterone may enhance the encoding and retrieval of verbal information. |

| Visuospatial Ability | The capacity to understand and remember spatial relationships among objects. | This is one of the more consistently reported areas of improvement, potentially linked to testosterone’s role in hippocampal function. |

| Executive Function | A set of higher-order processes including planning, problem-solving, and attention switching. | Results are highly variable. Some trials show no effect, while others note improvements in specific tasks. |

| Processing Speed | The speed at which the brain can process information and react. | Evidence for improvement in this area is generally weak. |

| Working Memory | The ability to hold and manipulate information for short periods. | The impact of TRT on working memory is not well-established, with most studies showing no significant change. |

The data suggests that TRT is not a panacea for all aspects of age-related cognitive change. Its effects appear to be targeted toward specific neural circuits, particularly those involved in memory systems where androgen receptors are highly concentrated.

The most promising results are often seen in men who start with both unequivocally low testosterone levels and some measurable cognitive impairment, indicating that the therapy is most effective when it is correcting a clear deficiency that is contributing to the problem.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of the relationship between testosterone and cognitive aging requires moving beyond a simple correlation and into the realm of molecular mechanisms. The central question evolves from “if” testosterone can prevent decline to “how” it modulates the cellular environment of the brain to confer resilience against neurodegenerative processes.

The academic inquiry focuses on two interconnected pathways ∞ the regulation of neuroinflammation and the preservation of synaptic plasticity. These processes are at the heart of neuronal health, and testosterone appears to be a key modulator of both. The inconsistent outcomes observed in human clinical trials likely reflect the complexity of these systems and the influence of individual genetic and metabolic factors.

A deep dive into the preclinical and molecular evidence, however, reveals a compelling biological rationale for testosterone’s role in maintaining cognitive capital.

The brain does not exist in isolation. It is exquisitely sensitive to the body’s inflammatory state. Chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation, often a feature of aging and metabolic dysfunction, is a powerful catalyst for cognitive decline.

Microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, can become chronically activated, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines that disrupt synaptic function and can even trigger neuronal apoptosis, or programmed cell death. Testosterone exerts a powerful anti-inflammatory effect, both systemically and within the central nervous system.

It appears to temper microglial activation and shift the cytokine profile away from a pro-inflammatory state. This action helps to quiet the background “noise” of inflammation, creating a more stable and supportive environment for neuronal communication and survival. This is a critical, permissive effect that underpins its more direct actions on neurons themselves.

Synaptic Plasticity and the Molecular Machinery of Memory

At the core of learning and memory is the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over time, a phenomenon known as long-term potentiation (LTP). This process is driven by a complex orchestra of intracellular signaling molecules. Research, particularly in animal models, has illuminated how testosterone influences this machinery. The binding of testosterone to androgen receptors (AR) in hippocampal neurons initiates a signaling cascade that upregulates the expression of key proteins essential for synaptic health.

One of the most critical of these is Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). BDNF is essential for neuronal survival, growth, and the maturation of synapses. Studies have shown that castration in male rodents leads to a significant decrease in hippocampal BDNF expression, an effect that is reversed by testosterone administration.

BDNF, in turn, activates another crucial player ∞ the transcription factor CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein). When phosphorylated (p-CREB), CREB travels to the cell nucleus and initiates the transcription of genes required for building and maintaining strong synapses.

Another vital structural component is Postsynaptic Density Protein-95 (PSD-95), an essential scaffolding protein that anchors neurotransmitter receptors in place at the postsynaptic terminal. Testosterone has been shown to increase the expression of both p-CREB and PSD-95, providing the direct molecular building blocks for enhanced synaptic connectivity and function. This pathway provides a clear, mechanistic link between the presence of testosterone and the brain’s capacity for robust synaptic plasticity.

Testosterone directly influences the genetic transcription of proteins essential for building and maintaining the synaptic structures that form the basis of memory.

The Androgen Receptor Independent Pathways

While the classical pathway involving direct binding to androgen receptors is well-documented, emerging evidence suggests that testosterone can also exert neuroprotective effects through AR-independent mechanisms. Some studies have utilized testicular feminization mutation (Tfm) mice, which have non-functional androgen receptors.

In these models, testosterone administration can still rescue some synaptic deficits, indicating that other signaling pathways are at play. One proposed mechanism is the local conversion of testosterone to estradiol by the enzyme aromatase within the brain. Estradiol can then act on estrogen receptors, which also play a role in neuroprotection and synaptic plasticity.

Another possibility involves testosterone’s ability to modulate cell membrane properties and influence kinase signaling cascades, such as the Erk1/2 pathway, which can then converge on downstream targets like CREB. This highlights the versatility of testosterone as a signaling molecule and suggests that its cognitive benefits may arise from a combination of genomic and non-genomic actions.

How Do Metabolic Factors Intersect with Hormonal Effects?

The discussion of testosterone’s cognitive effects is incomplete without considering its profound relationship with metabolic health. Hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome, particularly insulin resistance, are frequently co-occurring conditions. Insulin resistance in the body is often mirrored by insulin resistance in the brain, a state sometimes referred to as Type 3 diabetes.

This impairs the ability of neurons to take up and utilize glucose, their primary fuel source, leading to an energy crisis that compromises all cellular functions, including synaptic transmission and maintenance. Furthermore, the high levels of circulating insulin and glucose associated with metabolic syndrome are themselves pro-inflammatory, exacerbating the neuroinflammatory processes described earlier.

The table below details the intersection of these pathways, demonstrating how restoring hormonal balance can have cascading benefits for the brain’s metabolic environment.

| Molecular Pathway | Role in Cognitive Function | Influence of Testosterone | Intersection with Metabolic Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF/CREB Signaling | Promotes neuronal growth, survival, and synaptic plasticity. Essential for long-term memory formation. | Testosterone upregulates the expression of both BDNF and its downstream effector, p-CREB. | Insulin resistance and chronic inflammation suppress BDNF expression, creating a point of negative synergy. |

| Microglial Activation | The brain’s immune response. Chronic activation leads to neuroinflammation and neuronal damage. | Testosterone has anti-inflammatory properties and can temper the activation of microglia. | High glucose and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) are potent activators of microglia. |

| Synaptic Scaffolding (e.g. PSD-95) | Provides structural integrity to the synapse, anchoring receptors in place for efficient signaling. | Testosterone administration increases the expression of key scaffolding proteins like PSD-95. | Cellular energy deficits caused by insulin resistance impair the synthesis and transport of these vital proteins. |

| Amyloid-Beta Clearance | The removal of amyloid-beta peptides, the accumulation of which is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. | Some evidence suggests testosterone may modulate enzymes involved in amyloid processing and clearance. | Insulin-degrading enzyme also degrades amyloid-beta. In a state of hyperinsulinemia, this enzyme is preoccupied, impairing amyloid clearance. |

This systems-biology perspective reveals that testosterone therapy, when clinically indicated, functions as more than a simple hormone replacement. It is an intervention that can help correct fundamental metabolic and inflammatory dysfunctions that are key drivers of age-related cognitive decline.

The therapeutic benefit is likely derived from the synergistic effect of reducing neuroinflammation, improving cerebral glucose metabolism, and directly stimulating the molecular machinery of synaptic plasticity. The variability in clinical outcomes is therefore expected, as the net benefit to an individual will depend on their baseline inflammatory and metabolic state, as well as the underlying integrity of their neural circuits.

For men with significant metabolic and hormonal deficiencies, a combined approach that includes TRT alongside aggressive lifestyle and metabolic interventions may offer the greatest potential for preserving long-term cognitive health.

References

- Bhasin, S. et al. “Testosterone Therapy in Men with Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715 ∞ 1744.

- Jung, H. J. and S. W. Shin. “Effect of Testosterone Replacement Therapy on Cognitive Performance and Depression in Men with Testosterone Deficiency Syndrome.” The World Journal of Men’s Health, vol. 34, no. 3, 2016, pp. 194-199.

- Lazarou, C. et al. “Effects of androgen replacement therapy on cognitive function in patients with hypogonadism ∞ A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Biomedical Reports, vol. 22, no. 5, 2025, p. 34.

- Tan, S. et al. “Testosterone reduces hippocampal synaptic damage in an androgen receptor-independent manner.” Journal of Molecular Endocrinology, vol. 72, no. 1, 2023, d230064.

- Gong, M. et al. “Effects of testosterone on synaptic plasticity mediated by androgen receptors in male SAMP8 mice.” Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, vol. 68, no. 1, 2019, pp. 135-142.

- Beadell, A. J. and M. A. Spritzer. “Testosterone and Adult Neurogenesis.” Brain Sciences, vol. 12, no. 11, 2022, p. 1561.

- Morales, A. et al. “Diagnosis and management of testosterone deficiency syndrome in men ∞ clinical practice guideline.” Canadian Medical Association Journal, vol. 187, no. 18, 2015, pp. 1369-1377.

- Martin, D. et al. “Cognitive response to testosterone replacement added to intensive lifestyle intervention in older men with obesity and hypogonadism ∞ prespecified secondary analyses of a randomized clinical trial.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 115, no. 3, 2022, pp. 746-755.

- L-G, H. et al. “Testosterone Supplementation and Cognitive Functioning in Men ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 104, no. 10, 2019, pp. 4693 ∞ 4704.

- Jeong, Y. et al. “Effect of Testosterone Supplementation on Cognition in Elderly Men ∞ A Systematic Meta-Analysis.” Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research, vol. 25, no. 4, 2021, pp. 248-257.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map of the complex biological territory where hormones and cognition meet. It provides a framework for understanding the intricate systems that support mental clarity and the ways in which they can be disrupted by the process of aging.

This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of passive acceptance to one of proactive engagement with your own health. The journey of translating this scientific understanding into a personal health strategy is unique to each individual. It begins with an honest assessment of your own experience, your symptoms, and your goals.

Consider the subtle shifts you may have noticed in your own cognitive function. Think about your overall sense of vitality, your metabolic health, and the other systemic factors that contribute to your well-being. The data suggests that the most effective path forward is one that addresses the entire system, a holistic recalibration of the body’s internal environment.

This exploration is the first and most important step. The path to sustained vitality is built upon a foundation of deep self-knowledge and a partnership with clinical expertise. The potential to preserve your cognitive future rests within the actions you take today, guided by a clear understanding of your own unique biology.

Glossary

androgen receptors

pituitary gland

hypogonadism

cognitive function

metabolic health

cognitive decline

executive function

testosterone replacement therapy

anastrozole

gonadorelin

hpg axis

verbal memory

synaptic plasticity

studies have shown that

insulin resistance

testosterone therapy

neuroinflammation