Fundamentals

The question of how testosterone replacement therapy influences prostate health over many years is a deeply personal one. It touches upon fundamental aspects of male identity, vitality, and the anxieties that can accompany the aging process.

You may be experiencing a decline in energy, a loss of mental sharpness, or a diminished sense of well-being, and you are seeking a way to reclaim the man you know yourself to be. The conversation around hormonal optimization is often framed by this desire for restoration. Understanding the intricate relationship between testosterone and the prostate is a critical step in this journey, moving the discussion from a place of uncertainty to one of empowered knowledge.

For decades, the prevailing medical narrative was built on a seemingly simple equation ∞ testosterone feeds prostate cancer. This idea originated from landmark research in the 1940s showing that castration, which dramatically lowers testosterone, caused prostate tumors to regress. Conversely, administering testosterone to a man with metastatic prostate cancer appeared to accelerate the disease.

This created a powerful and enduring belief that elevating testosterone through therapy was akin to pouring fuel on a fire, a risk that for many years overshadowed any potential benefits for men with low testosterone levels. This historical context is important because it shaped the cautious, and sometimes fearful, perspective that many clinicians and patients still carry today.

The Prostate Gland a Brief Introduction

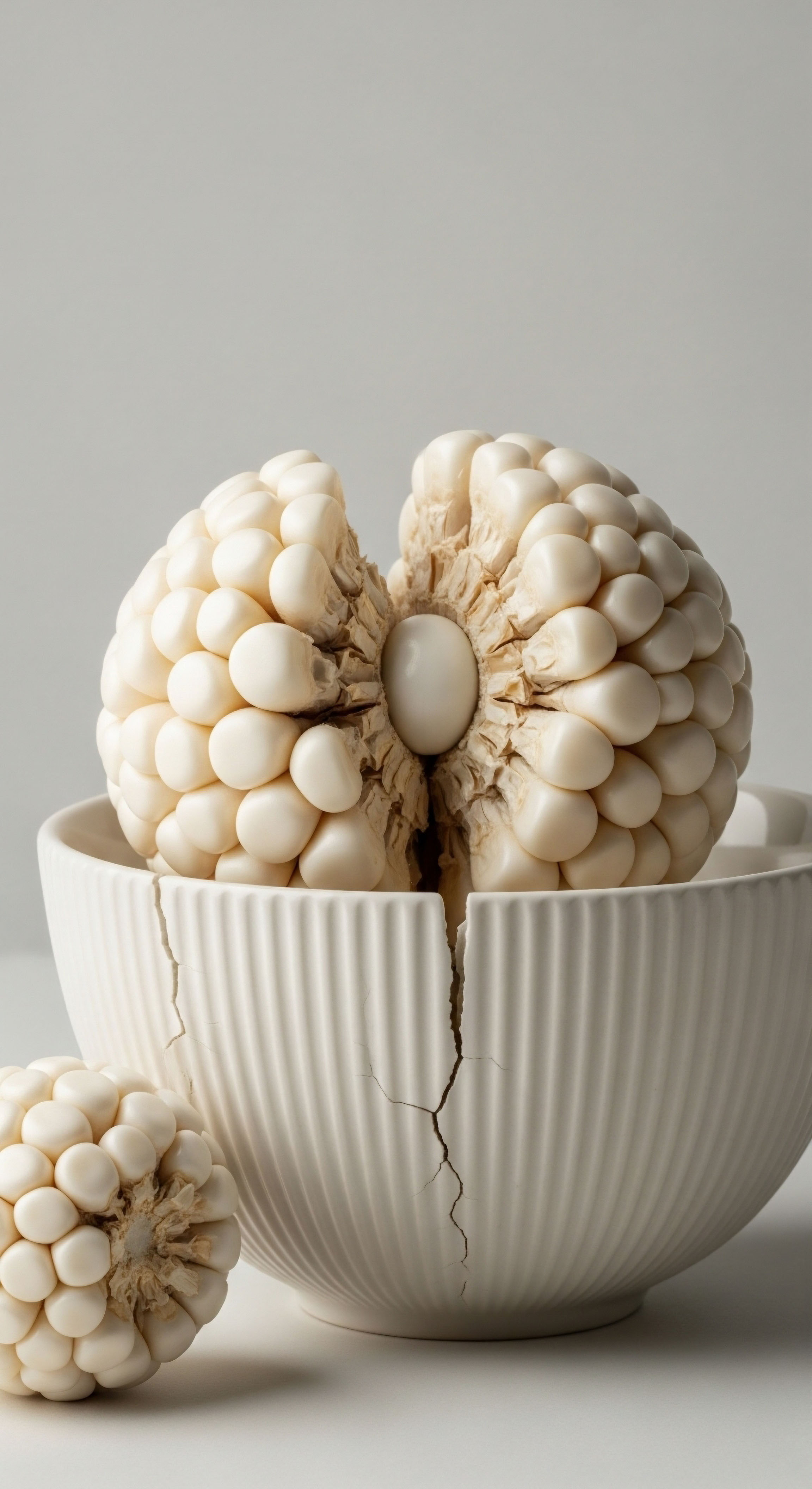

To appreciate the nuances of this topic, we must first understand the prostate itself. The prostate is a small gland, about the size of a walnut, located just below the bladder and in front of the rectum. Its primary biological function is to produce seminal fluid, the liquid that nourishes and transports sperm.

The prostate is an androgen-dependent organ, meaning its growth and function are regulated by male hormones, principally testosterone and its more potent derivative, dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Testosterone is converted to DHT within the prostate by an enzyme called 5-alpha reductase. DHT is a key driver of normal prostate development during puberty and maintains its function throughout adult life.

The prostate’s lifelong sensitivity to androgens is central to the discussion of TRT. As men age, two common prostate-related conditions emerge ∞ benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer. BPH is a non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate that can cause urinary symptoms, such as a frequent urge to urinate, a weak stream, and incomplete bladder emptying.

Prostate cancer is a malignant growth of cells within the prostate gland. Because both conditions involve prostate tissue growth, and because that growth is known to be influenced by androgens, the concern that TRT could worsen these conditions is biologically plausible.

Revisiting the Old Dogma

Recent decades of clinical research have compelled a significant re-evaluation of the traditional view. A growing body of evidence from numerous studies, including randomized controlled trials, has challenged the direct and linear relationship between testosterone levels and prostate cancer risk.

The TRAVERSE trial, a large-scale study, found that testosterone therapy over an average of 33 months did not significantly increase the incidence of prostate cancer in men with low testosterone. This does not mean the old observations were wrong; it means they were incomplete. The men in the original studies already had advanced, metastatic prostate cancer, a very different biological state from a healthy prostate or even early, localized cancer.

The modern understanding of testosterone’s effect on the prostate is more nuanced, suggesting a saturation point beyond which higher testosterone levels do not further stimulate prostate tissue.

This has led to the development of the Prostate Saturation Model. This model proposes that androgen receptors in the prostate become fully saturated at relatively low testosterone levels. Once these receptors are saturated, providing additional testosterone does not produce a proportional increase in prostate tissue stimulation.

Think of it like a sponge that is already full of water; pouring more water on it will not make it any wetter. This concept helps explain why men with low testosterone who start TRT may see an initial, small rise in their Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) levels, but this rise typically plateaus. It also helps explain why there isn’t a direct correlation between high-normal testosterone levels and an increased risk of developing prostate cancer.

This evolving understanding shifts the focus from a simple fear of testosterone to a more sophisticated approach centered on careful patient selection, individualized treatment protocols, and diligent monitoring. The goal is to restore testosterone to a healthy physiological range, not to create unnaturally high levels.

For the man seeking to understand his own body and make informed decisions, this represents a critical shift. It moves the conversation from a simple “Is it safe?” to a more empowering “How can it be done safely for me?”.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational concepts, a deeper clinical perspective is necessary to understand how testosterone replacement therapy is managed to support long-term prostate health. This involves a detailed look at the specific protocols, monitoring strategies, and the biological mechanisms that underpin them.

For the individual on a hormonal optimization journey, this knowledge is empowering, transforming them from a passive recipient of care into an active, informed partner in their own wellness. The conversation now shifts to the practical application of scientific principles to ensure that the benefits of therapy are realized while potential risks are meticulously managed.

The clinical management of TRT is a proactive process. It begins with a thorough baseline assessment to establish a clear picture of the patient’s prostate health before therapy is initiated. This initial evaluation is not merely a screening tool; it is the first data point in a long-term surveillance strategy.

The ongoing monitoring during therapy is designed to detect any subtle changes that might warrant further investigation or a modification of the treatment plan. This systematic approach is the cornerstone of responsible and effective hormonal optimization.

Core Monitoring Protocols for Prostate Health

A well-structured TRT program incorporates several key monitoring tools to track prostate health over time. These tools provide objective data that, when interpreted in the context of the individual’s overall health, allow for a highly personalized approach to care.

- Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Testing ∞ PSA is a protein produced by both normal and cancerous prostate cells. While an elevated PSA can be an indicator of prostate cancer, it can also be caused by other conditions like BPH or prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate). On TRT, it is common to see a small initial increase in PSA, which then typically stabilizes. The absolute PSA value is important, but clinicians also pay close attention to the PSA velocity (the rate of change over time) and PSA density (the PSA level relative to the size of the prostate). A rapid or sustained increase in PSA would prompt further evaluation.

- Digital Rectal Exam (DRE) ∞ The DRE is a physical examination that allows the clinician to feel the surface of the prostate for any abnormalities, such as nodules, hardness, or asymmetry. While its use as a standalone screening tool has been debated, in the context of TRT, it provides a valuable physical assessment that complements the biochemical data from the PSA test. It is typically performed at baseline and then annually or more frequently if indicated.

- International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) ∞ This is a standardized questionnaire that assesses the severity of urinary symptoms associated with BPH. By tracking the IPSS score over time, clinicians can objectively measure whether TRT is affecting a patient’s urinary function. Interestingly, some studies have shown that TRT can actually improve lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in some men, possibly by improving bladder muscle tone and reducing inflammation.

The Role of Estrogen and DHT in the Prostate Equation

Testosterone does not act in isolation. Its effects on the prostate are mediated through its conversion into two other key hormones ∞ dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and estradiol (an estrogen). Understanding the role of these metabolites is crucial for a comprehensive view of prostate health during TRT.

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is a significantly more potent androgen than testosterone. As mentioned, it is synthesized within the prostate by the enzyme 5-alpha reductase. DHT is the primary driver of prostate growth, both benign and malignant. While TRT will increase testosterone levels, the subsequent increase in DHT can be managed.

In some protocols, particularly for men with a history of BPH or hair loss, a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor like finasteride or dutasteride may be considered to mitigate the conversion of testosterone to DHT. However, this is a nuanced decision, as DHT also has positive systemic effects, and reducing it can have its own side effects.

Estradiol is produced from testosterone through a process called aromatization, which occurs in various tissues, including fat cells. The balance between testosterone and estradiol is critically important for overall health, and this balance extends to the prostate. Both high and low levels of estradiol have been implicated in prostate issues.

Elevated estradiol, often seen in men with higher body fat, can contribute to BPH symptoms and may play a role in prostate cancer development. For this reason, many TRT protocols for men include an aromatase inhibitor like anastrozole. This medication blocks the conversion of testosterone to estradiol, helping to maintain a healthy androgen-to-estrogen ratio. Careful management of estradiol levels is a key component of a sophisticated TRT regimen.

Comparing TRT Protocols and Their Potential Prostate Impact

The method of testosterone administration can influence hormonal fluctuations and, potentially, the impact on the prostate. Different protocols have different pharmacokinetic profiles, meaning they are absorbed, distributed, and eliminated by the body in different ways.

| Modality | Hormonal Profile | Prostate-Related Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Intramuscular Injections (e.g. Testosterone Cypionate) | Creates peaks and troughs in testosterone levels. More frequent injections (e.g. twice weekly) can mitigate this. | The peaks can lead to higher transient levels of testosterone and its metabolites. Estradiol management with an aromatase inhibitor is often necessary. |

| Transdermal Gels | Provides relatively stable, daily testosterone levels. | Can lead to higher conversion to DHT in the skin. There is also a risk of transference to others. The TRAVERSE study primarily used transdermal testosterone. |

| Subcutaneous Pellets | Delivers a steady, long-term release of testosterone over 3-6 months. | Provides very stable levels, which may be beneficial for prostate health. However, dose adjustments are less flexible than with other methods. |

The choice of protocol is a clinical decision made in partnership with the patient, taking into account their lifestyle, preferences, and specific physiological needs. Regardless of the modality chosen, the principles of diligent monitoring remain the same. The goal is always to maintain physiological hormone levels and a healthy balance among testosterone, DHT, and estradiol, thereby supporting overall well-being while safeguarding prostate health.

Academic

An academic exploration of the long-term relationship between testosterone replacement therapy and prostate health requires a departure from broad clinical guidelines into the granular details of molecular biology, epidemiology, and advanced clinical trial analysis. This perspective is grounded in a mechanistic understanding of androgen signaling pathways and a critical appraisal of the evidence that has shaped our current clinical paradigms.

We will focus specifically on the Androgen Saturation Model as a central hypothesis and examine the data that supports, refines, or challenges this concept. This deep dive is essential for appreciating the sophisticated interplay between hormonal physiology and prostate cellular behavior.

The historical association of testosterone with prostate cancer progression is rooted in the work of Huggins and Hodges, which earned them a Nobel Prize. Their research demonstrated that androgen deprivation caused regression of metastatic prostate cancer. This led to the logical, yet ultimately oversimplified, conclusion that higher testosterone levels must promote prostate cancer development (the “androgen hypothesis”).

For over 60 years, this hypothesis dominated clinical thinking, leading to a strong contraindication for TRT in men with a history of prostate cancer and significant caution in all other men. However, subsequent research has failed to consistently demonstrate a positive correlation between endogenous serum testosterone levels and prostate cancer risk. In fact, some studies have suggested that low testosterone may be associated with more aggressive prostate cancer.

The Molecular Basis of the Saturation Model

The Saturation Model provides a compelling biological framework to reconcile these seemingly contradictory findings. Its central tenet is that the androgen receptor (AR), the protein within prostate cells that binds to testosterone and DHT, has a finite capacity for stimulation. At a molecular level, the process works as follows:

- Binding and Dimerization ∞ Testosterone or DHT enters the prostate cell and binds to an AR in the cytoplasm. This binding event causes a conformational change in the AR.

- Nuclear Translocation ∞ The hormone-receptor complex then translocates into the cell nucleus.

- DNA Binding and Gene Transcription ∞ Inside the nucleus, the complex binds to specific DNA sequences known as Androgen Response Elements (AREs) in the promoter regions of target genes. This binding initiates the transcription of genes that regulate cell growth, proliferation, and the production of proteins like PSA.

The saturation concept posits that at very low (hypogonadal) levels of testosterone, there are many unbound ARs. In this state, an increase in testosterone leads to a significant increase in AR binding and subsequent gene transcription, resulting in prostate cell growth and a rise in PSA.

However, once testosterone levels reach a certain threshold (estimated to be around 200-250 ng/dL), the vast majority of ARs become occupied or saturated. Beyond this point, further increases in serum testosterone do not lead to a proportional increase in AR-mediated gene transcription. The system is already operating at or near its maximum capacity.

This explains why administering TRT to a hypogonadal man can raise his PSA, but a man with a testosterone level of 600 ng/dL does not necessarily have a higher prostate cancer risk than a man with a level of 400 ng/dL.

Evidence from Clinical and Epidemiological Studies

A substantial body of evidence lends support to the Saturation Model. Multiple large-scale epidemiological studies have failed to find a link between higher endogenous testosterone levels and an increased risk of developing prostate cancer. A meta-analysis of 18 prospective studies found no association between serum concentrations of various androgens, including testosterone, and prostate cancer risk.

Furthermore, studies involving men on TRT have provided direct evidence. The TRAVERSE trial, a large, randomized, placebo-controlled study, is a landmark in this area. While its primary endpoint was cardiovascular safety, it included a thorough evaluation of prostate outcomes.

Over a median follow-up of 33 months, the incidence of prostate cancer was low and not significantly different between the testosterone and placebo groups (0.55% vs. 0.57%, respectively). Importantly, there was no difference in the incidence of high-grade prostate cancer. While PSA levels did rise slightly more in the testosterone group, the mean difference was small and not considered clinically significant for most patients.

The TRAVERSE trial provides robust, contemporary evidence that TRT, when used to restore physiological testosterone levels in aging men with hypogonadism, does not increase the risk of prostate cancer over a period of several years.

Another line of evidence comes from studies of men with a history of prostate cancer who have undergone TRT after successful treatment (e.g. radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy). While this was once considered an absolute contraindication, a growing number of studies have shown that in carefully selected patients with low-risk disease and no evidence of recurrence, TRT does not appear to increase the risk of cancer recurrence.

These studies are typically small and require very careful patient selection and monitoring, but they further challenge the old dogma and support the idea that the relationship between testosterone and prostate cancer is far more complex than a simple dose-response curve.

What Are the Unanswered Questions and Future Directions?

Despite the reassuring data from recent trials, important questions remain. The duration of most randomized controlled trials, including TRAVERSE, is limited to a few years. The influence of TRT on prostate health over decades is still an area that requires further long-term observational data.

Additionally, the majority of trial participants have been men with low-to-intermediate risk profiles. The safety of TRT in men at very high risk for prostate cancer, or in men with a history of high-grade disease, is less clear.

Future research will likely focus on several key areas:

- Long-Term Registry Data ∞ Establishing large, multi-center registries to follow men on TRT for 10, 15, or even 20 years will be critical for understanding the very long-term effects on the prostate.

- Genetic Factors ∞ Investigating how genetic variations in the androgen receptor or other hormone-related genes might influence an individual’s prostate response to TRT.

- The Role of Inflammation ∞ Exploring the interplay between hormonal optimization, chronic inflammation, and prostate health. TRT has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects in some contexts, which could be a confounding variable in its overall impact on the prostate.

The academic perspective on TRT and prostate health has evolved from a position of prohibition to one of cautious optimism and diligent scientific inquiry. The Saturation Model provides a robust framework for our current understanding, supported by a growing body of high-quality clinical evidence. The focus has shifted from avoiding testosterone to understanding how to use it intelligently and safely, grounded in a deep appreciation for the underlying molecular and physiological mechanisms.

| Study/Analysis | Type | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous Hormones and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group (2008) | Meta-analysis of 18 prospective studies | No association found between serum androgen levels and prostate cancer risk. |

| Calof et al. (2005) | Meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials | No statistically significant increase in prostate cancer diagnoses among men on TRT compared to placebo. |

| TRAVERSE Study (Bhasin et al. 2023) | Large randomized, placebo-controlled trial | No significant difference in the incidence of prostate cancer between the testosterone and placebo groups over a median of 33 months. |

| Loeb et al. (2017) | Large nested case-control study | TRT was not associated with an overall increased risk of prostate cancer, but was associated with a reduced risk of aggressive prostate cancer. |

References

- Yassin, A. A. & El-Sakka, A. I. (2019). The effects of testosterone replacement therapy on the prostate ∞ a clinical perspective. Translational Andrology and Urology, 8 (Suppl 2), S170 ∞ S179.

- Bhasin, S. et al. (2023). Prostate Safety Events During Testosterone Replacement Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism ∞ A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open, 6(12), e2348269.

- Morgentaler, A. (2016). The great testosterone myth. McGill Journal of Medicine, 18(1), 65-70.

- Khera, M. (2017). Adverse effects of testosterone replacement therapy ∞ an update on the evidence and controversy. Therapeutic Advances in Urology, 9(1), 21-30.

- Endogenous Hormones and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group. (2008). Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer ∞ a collaborative analysis of 18 prospective studies. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 100(3), 170-183.

- Calof, O. M. et al. (2005). Adverse events associated with testosterone replacement in middle-aged and older men ∞ a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. The Journals of Gerontology Series A ∞ Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 60(11), 1451-1457.

- Loeb, S. et al. (2017). Testosterone replacement therapy and risk of favorable and aggressive prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 35(13), 1430-1436.

- Shigehara, K. et al. (2011). Effect of testosterone replacement therapy on lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with late-onset hypogonadism. Aging Male, 14(1), 45-49.

- Tan, W. S. et al. (2013). A randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of testosterone undecanoate (Nebido®) in the treatment of testosterone deficiency in aging men. BJU International, 112(4), 553-561.

- Bhasin, S. et al. (2010). Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 95(6), 2536-2559.

Reflection

You have now journeyed through the historical context, clinical practices, and deep scientific reasoning surrounding testosterone therapy and its long-term influence on the prostate. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It allows you to move past the outdated, fear-based narratives and engage with your health from a position of clarity and confidence.

The information presented here is designed to be a map, showing you the terrain of your own biology and the pathways available for optimizing your function and vitality.

Consider the initial questions that brought you here. Were they rooted in a desire to feel better, to reclaim a sense of self that has felt distant? Or were they driven by concerns about the safety and long-term implications of a potential treatment path?

The science we have explored provides a robust framework for answering these questions, but it is not the final word. Your personal health story, your unique physiology, and your individual goals are the variables that complete the equation.

What Is the Next Step on Your Personal Health Journey?

This exploration is the beginning of a conversation. It is the foundation upon which a truly personalized wellness protocol is built. The path forward involves integrating this objective, scientific understanding with your own subjective experience. How do you feel? What are your goals for the next chapter of your life?

Answering these questions honestly is as important as any lab test or clinical study. The ultimate aim is to create a state of well-being that is not just defined by the absence of disease, but by the presence of strength, clarity, and resilience. Your biology is not your destiny; it is your starting point.