Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A persistent fatigue that sleep does not touch, a shift in your mood that seems disconnected from your daily life, or a change in your body’s composition that diet and exercise no longer seem to influence.

These experiences are not isolated incidents; they are signals from a complex, internal communication network. Your body is sending messages through its endocrine system, and the sense of dysregulation you are experiencing is a sign that this communication has been disrupted. The question of whether nutritional choices can reverse these disruptions is a deeply personal one, tied to the desire to reclaim a sense of control over your own biological experience.

The answer begins with understanding the nature of hormones themselves. These molecules are the architects of your daily existence, regulating everything from your metabolism and sleep-wake cycles to your stress response and reproductive health. They are synthesized from the very building blocks you consume ∞ proteins, fats, and cholesterol.

A diet lacking in high-quality sources of these macronutrients effectively starves the production lines for these critical signaling molecules. Your body cannot construct testosterone, estrogen, or thyroid hormones from inadequate raw materials. This foundational link between what you eat and how you feel is the first principle of hormonal health.

The Symphony of Systems

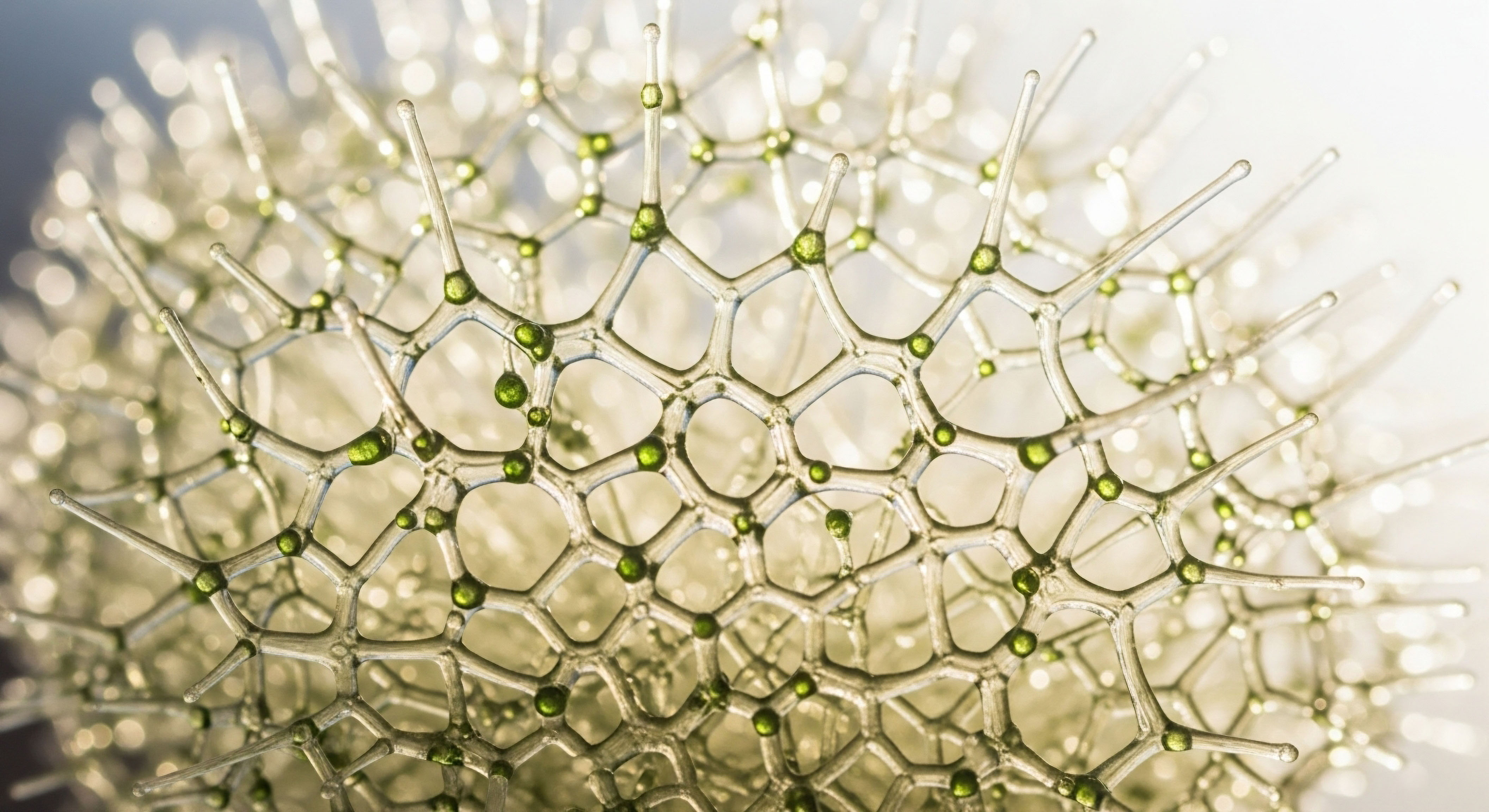

Your endocrine system does not operate in isolation. It is in constant dialogue with your nervous system, your immune system, and, most intimately, your digestive system. The health of your gut is profoundly linked to hormonal balance. A specialized collection of bacteria in your gut, known as the estrobolome, is responsible for metabolizing and helping to regulate the body’s circulating estrogen.

When the gut microbiome is imbalanced ∞ a state known as dysbiosis ∞ this process can be impaired, leading to either a deficiency or an excess of active estrogen, contributing to symptoms like irregular cycles or mood swings.

Furthermore, chronic low-grade inflammation, often driven by a diet high in processed foods and refined sugars, can interfere with hormone receptor sensitivity. Imagine your hormones as keys and your cells’ receptors as locks. Inflammation can effectively “gum up” these locks, making it harder for the keys to fit.

Even if your body is producing adequate levels of a hormone, your cells cannot properly receive its message. This is a common scenario in conditions like insulin resistance, where cells become less responsive to the signal of insulin, leading to dysregulated blood sugar and a cascade of metabolic consequences.

Understanding that your symptoms are a logical, biological response to your internal environment is the first step toward recalibrating your system.

Building Blocks for Balance

Re-establishing hormonal equilibrium through nutrition involves a dual strategy ∞ providing the necessary components for hormone synthesis while simultaneously reducing the inflammatory and metabolic interference that disrupts their function. This process is not about a single “superfood” or a restrictive diet. It is a systematic approach to supporting the body’s innate regulatory mechanisms.

Key nutritional components play specific roles in this process:

- High-Quality Proteins ∞ These provide the essential amino acids required for the production of peptide hormones, which regulate appetite, metabolism, and stress.

- Healthy Fats ∞ Cholesterol and specific fatty acids are the direct precursors to all steroid hormones, including cortisol, DHEA, testosterone, and estrogens. Omega-3 fatty acids, in particular, are instrumental in building healthy cell membranes, which improves receptor function and helps to lower systemic inflammation.

- Fiber ∞ Soluble and insoluble fiber are critical for maintaining stable blood sugar levels and supporting gut health. A healthy gut microbiome, nourished by fiber, is essential for the proper elimination of metabolized hormones, preventing their recirculation and accumulation.

- Micronutrients ∞ Vitamins and minerals act as the spark plugs in the engine of hormone production. Zinc is essential for testosterone production and thyroid health, selenium is required for the conversion of inactive thyroid hormone to its active form, and B vitamins are critical for managing the body’s stress response.

By focusing on a nutrient-dense diet rich in these elements, you are not merely treating symptoms. You are providing your body with the fundamental tools it needs to repair its communication pathways and restore a state of functional balance. This is a journey from feeling like a passenger in your own body to becoming an informed and active participant in your health.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational principles, we can examine the specific ways that targeted nutritional protocols can address distinct patterns of hormonal dysregulation. This involves a more granular understanding of how different dietary strategies influence specific hormonal axes, such as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis that governs our stress response, or the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis that controls reproductive health. The goal is to match the nutritional intervention to the underlying biological mechanism of the imbalance.

Regulating Insulin and Androgens in PCOS

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder in women, characterized by insulin resistance, elevated androgen levels (like testosterone), and irregular menstrual cycles. Insulin resistance is a key driver of the condition; when cells become less responsive to insulin, the pancreas compensates by producing more of it. These high insulin levels then stimulate the ovaries to produce excess androgens, disrupting ovulation and contributing to many PCOS symptoms.

Nutritional interventions for PCOS center on improving insulin sensitivity. A diet with a low glycemic load, which minimizes sharp spikes in blood sugar, is a cornerstone of this approach. This involves prioritizing whole, unprocessed carbohydrates rich in fiber over refined grains and sugars. Specific micronutrients also play a significant role. Myo-inositol, a member of the B-vitamin complex, has been shown in numerous studies to improve insulin sensitivity and restore ovulatory function in women with PCOS.

Comparing Dietary Approaches for PCOS

While the principle of glycemic control is central, different dietary frameworks can be used to achieve it. The choice of approach can be tailored to an individual’s metabolic profile and preferences.

| Dietary Approach | Mechanism of Action | Key Foods | Primary Hormonal Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean Diet | Reduces inflammation, improves insulin sensitivity through high intake of monounsaturated fats and fiber. | Olive oil, fatty fish, nuts, seeds, legumes, vegetables, whole grains. | Insulin, Leptin |

| Low-Carbohydrate/Ketogenic Diet | Lowers insulin levels dramatically by minimizing carbohydrate intake, promoting a switch to fat metabolism. | Avocados, healthy oils, nuts, seeds, non-starchy vegetables, meat, fish. | Insulin, Androgens |

| DASH Diet | Originally for hypertension, its emphasis on fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins helps improve metabolic markers. | Fruits, vegetables, lean protein, low-fat dairy, whole grains. | Insulin, Cortisol |

Supporting Thyroid and Adrenal Function

The thyroid and adrenal glands are intricately linked. The thyroid, your body’s metabolic thermostat, produces hormones that regulate energy expenditure in every cell. The adrenal glands manage the stress response through hormones like cortisol. Chronic stress can suppress thyroid function, and an underactive thyroid can impair the body’s ability to cope with stress. Nutritional support for this axis must therefore address both systems.

Thyroid hormone production is dependent on a suite of specific micronutrients:

- Iodine and L-Tyrosine ∞ These are the direct building blocks of the thyroid hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3).

- Selenium ∞ This mineral is a critical cofactor for the enzyme 5′-deiodinase, which converts the inactive T4 hormone into the biologically active T3 form in peripheral tissues.

- Zinc and Iron ∞ Deficiencies in these minerals can also impair the T4 to T3 conversion and overall thyroid function.

Simultaneously, supporting the adrenal glands involves stabilizing blood sugar to prevent cortisol spikes and providing the nutrients consumed by the stress response, such as Vitamin C, B-complex vitamins (especially B5), and magnesium. An anti-inflammatory dietary pattern helps to lower the overall physiological stress load on the body, allowing the HPA axis to recalibrate.

Targeted nutrition provides the specific substrates and cofactors required to restore function to compromised hormonal pathways.

How Does Diet Influence Estrogen Metabolism?

The body must not only produce hormones but also effectively metabolize and excrete them. Estrogen, in particular, undergoes a two-phase detoxification process in the liver. Nutritional choices can significantly support this process. Cruciferous vegetables (like broccoli, cauliflower, and kale) contain a compound called indole-3-carbinol, which promotes a healthier pathway of estrogen metabolism in the liver.

Furthermore, adequate fiber intake is essential for binding to metabolized estrogens in the gut and ensuring their excretion. When gut health is poor or fiber is lacking, an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase can un-bind these estrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed into circulation and contributing to a state of estrogen dominance.

By understanding these specific biochemical pathways, nutritional interventions can be precisely targeted. This moves beyond a general “healthy diet” to a functional approach designed to correct specific points of failure within the endocrine system. It is a clinical application of nutrition, using food as a tool to modulate the body’s complex internal chemistry.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of nutritional endocrinology requires moving beyond the direct inputs for hormone synthesis and into the complex, systems-level interactions that govern hormonal homeostasis. One of the most dynamic and clinically significant areas of research is the interplay between the gut microbiome, intestinal barrier integrity, and the regulation of sex hormones. This relationship provides a powerful example of how targeted nutritional strategies can fundamentally alter endocrine function by modulating the body’s microbial ecosystem and inflammatory status.

The Estrobolome a Key Regulator of Systemic Estrogen

The term estrobolome refers to the aggregate of enteric bacterial genes whose products are capable of metabolizing estrogens. The primary mechanism involves the secretion of the enzyme β-glucuronidase by certain gut microbes. In the liver, estrogens are conjugated (primarily glucuronidated) to render them water-soluble for excretion into the bile, which then enters the intestinal tract.

High β-glucuronidase activity in the gut can deconjugate these estrogens, releasing them in their active, unbound form to be reabsorbed into circulation via the enterohepatic circulation. This process can significantly increase the body’s total exposure to estrogen, contributing to the pathophysiology of estrogen-dominant conditions.

A diet low in fiber and high in processed fats can alter the composition of the gut microbiome, favoring bacteria with high β-glucuronidase activity. Conversely, a diet rich in diverse plant fibers (prebiotics) promotes the growth of beneficial species, such as Lactobacillus, which have been shown to have low β-glucuronidase activity.

Furthermore, certain dietary compounds, like calcium-D-glucarate found in many fruits and vegetables, act as β-glucuronidase inhibitors, directly reducing the deconjugation of estrogens in the gut.

The gut microbiome functions as a distinct endocrine organ, actively modulating the body’s hormonal milieu through specific enzymatic actions.

Intestinal Permeability and Endocrine Disruption

The integrity of the intestinal barrier is another critical factor. Chronic gut inflammation, driven by dietary factors, infections, or stress, can lead to increased intestinal permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut.” This condition allows for the translocation of bacterial components, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), from the gut lumen into systemic circulation. LPS is a potent endotoxin that triggers a strong inflammatory response from the immune system.

This systemic inflammation has profound effects on the endocrine system. It can suppress the function of the HPG axis, impairing the production of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. It also directly interferes with ovarian function, reducing steroidogenesis.

Furthermore, the chronic inflammatory state increases peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens via the aromatase enzyme, which is upregulated by inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6. This creates a vicious cycle where gut-derived inflammation disrupts central hormonal control while simultaneously altering peripheral hormone metabolism.

Nutritional Modulation of Gut-Hormone Axis

A clinical nutritional strategy must therefore aim to both reshape the microbiome and restore intestinal barrier function. This is a multi-pronged approach grounded in biochemical and microbiological principles.

| Intervention Target | Biochemical Mechanism | Key Nutritional Components | Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiome Reshaping (Estrobolome) | Promote beneficial bacteria, reduce β-glucuronidase activity, inhibit pathogenic species. | Prebiotic fibers (inulin, FOS), Probiotic foods (fermented vegetables), Polyphenols (berries, green tea), Calcium-D-glucarate. | Improved estrogen clearance, reduced enterohepatic recirculation of estrogens. |

| Intestinal Barrier Repair | Provide fuel for enterocytes, support tight junction protein expression, reduce inflammation. | L-Glutamine, Zinc, Vitamin A, Vitamin D, Omega-3 Fatty Acids (EPA/DHA), Collagen peptides. | Decreased intestinal permeability, reduced translocation of LPS, lower systemic inflammation. |

| Liver Detoxification Support (Phase I & II) | Provide cofactors for cytochrome P450 enzymes and conjugation pathways (sulfation, glucuronidation). | Cruciferous vegetables (sulforaphane), B-vitamins, Magnesium, Selenium, Amino acids (glycine, taurine). | Efficient metabolism and preparation of hormones for excretion. |

What Is the Role of Nutrigenomics in Hormonal Health?

The future of nutritional endocrinology lies in personalization, guided by the field of nutrigenomics. This science studies how individual genetic variations, or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), affect the body’s response to specific nutrients. For example, an individual may have a SNP in the MTHFR gene, which can impair folate metabolism and, by extension, the methylation pathways critical for estrogen detoxification.

Another person might have a variation in the COMT gene, which affects the breakdown of catecholamines and catechol-estrogens. For these individuals, a generic nutritional recommendation may be insufficient. A nutrigenomic approach allows for the creation of highly personalized protocols, such as recommending a specific form of folate or providing targeted support for COMT activity, to address these innate biochemical tendencies.

This represents the ultimate application of targeted nutrition ∞ an intervention tailored not just to the hormonal imbalance, but to the unique genetic blueprint of the individual experiencing it.

References

- Baker, J. M. Al-Nakkash, L. & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. “Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

- Cutler, D. A. Pride, S. M. & Cheung, A. P. “Low-glycemic index diet and lifestyle modification in polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a randomized controlled trial.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, vol. 41, no. 4, 2019, pp. 496-504.

- González, F. “Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction.” Steroids, vol. 77, no. 4, 2012, pp. 300-305.

- Kresser, Chris. The Paleo Cure ∞ 21 Days to a New You. Little, Brown and Company, 2013.

- He, S. & Li, H. “The gut microbiome and female reproductive health.” Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE B (Biomedicine & Biotechnology), vol. 22, no. 3, 2021, pp. 155-164.

- Hyman, Mark. The Blood Sugar Solution ∞ The Ultra-Healthy Program for Losing Weight, Preventing Disease, and Feeling Great Now!. Little, Brown and Company, 2012.

- Rayman, M. P. “Selenium and human health.” The Lancet, vol. 379, no. 9822, 2012, pp. 1256-1268.

- Salas-Huetos, A. et al. “The Role of Diet on Gut Microbiota, Inflammation and Male Fertility.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 12, 2021, p. 673457.

- Santoro, Nanette, et al. “Role of nutrition and exercise in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 92, no. 7, 2007, pp. 2447-2455.

- Trickey, Ruth. Women, Hormones and the Menstrual Cycle. Allen & Unwin, 2003.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Compass

The information presented here is more than a collection of biological facts; it is a framework for understanding the language of your own body. The symptoms that prompted your search are not random points of failure. They are coherent, logical signals that your internal environment is out of balance.

Viewing your body through this lens shifts the perspective from one of passive suffering to one of active, informed participation. The knowledge that the composition of your meals directly influences the molecules that govern your mood, energy, and vitality is profoundly empowering.

This journey of recalibration is deeply personal. The specific nutritional strategies that will restore your unique system to equilibrium will depend on your individual biochemistry, your genetics, your life history, and the specific nature of your hormonal disruption. The path forward involves a process of careful observation, of listening to the feedback your body provides as you make changes. It is a partnership with your own physiology.

Consider this knowledge not as a final destination, but as the map and compass for your journey. The terrain is your own body, and the goal is to navigate it with skill and awareness. The ultimate aim is to restore the system’s innate intelligence, allowing you to function with the vitality that is your biological birthright. This process is the foundation upon which a truly personalized and proactive approach to wellness is built.