Fundamentals

The feeling is unmistakable. It is a subtle, persistent sense of being out of sync with your own body. It might manifest as a fatigue that sleep does not resolve, a change in mood that feels untethered to your daily life, or a shift in your body’s composition that seems to defy your efforts with diet and exercise.

This experience, far from being imagined, is often the first signal that your body’s intricate internal communication network ∞ the endocrine system ∞ is operating under strain. Your hormones are the messengers in this system, a complex chemical language that dictates everything from your energy levels and metabolic rate to your stress response and reproductive health. Understanding that your symptoms are a valid biological narrative is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

The question of whether nutritional choices can restore hormonal equilibrium is a profound one. The answer is anchored in the biological reality that nutrition provides the fundamental raw materials for hormonal production and function. Your body does not create hormones from nothing; it synthesizes them from the fats, proteins, and micronutrients you consume.

Cholesterol, for instance, is the precursor to all steroid hormones, including cortisol and the sex hormones estrogen and testosterone. The amino acid tyrosine is indispensable for the creation of thyroid hormones. Without these essential substrates, the endocrine system simply cannot perform its duties. Targeted nutritional interventions, therefore, are a direct conversation with your cellular machinery, providing the precise resources needed to build, transport, and receive hormonal signals effectively.

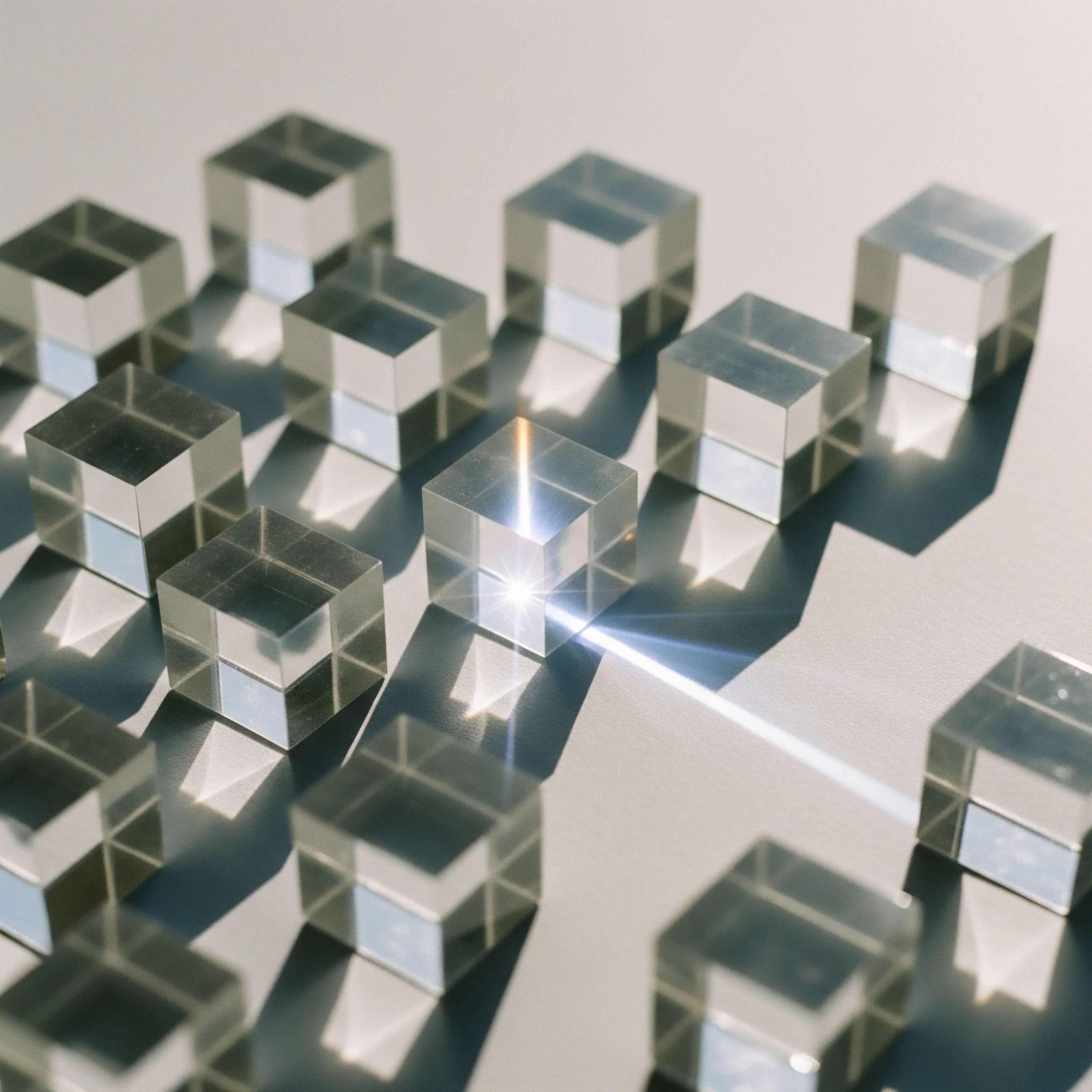

Your body’s hormonal balance is a direct reflection of its internal chemistry, which is profoundly influenced by the nutrients it receives.

The Symphony of Hormonal Interaction

It is useful to conceptualize the endocrine system as a finely tuned orchestra. Each hormone is an instrument, and for the symphony of health to play harmoniously, each instrument must be in tune and play its part at the correct time and volume. A single discordant note can throw off the entire composition.

The primary conductors of this orchestra are insulin and cortisol. Insulin, released in response to glucose from carbohydrates, is a master regulator of energy storage. Chronic excess insulin, often driven by a diet high in processed carbohydrates and sugars, can lead to insulin resistance. This condition means cells become “deaf” to insulin’s signal, forcing the pancreas to produce more and creating a state of metabolic chaos that disrupts other hormonal systems, including those governing the ovaries and testes.

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, is designed for short-term, acute challenges. In modern life, however, chronic stress maintains elevated cortisol levels, which can suppress thyroid function and impair the production of sex hormones. The body, perceiving a constant state of emergency, prioritizes survival (cortisol production) over other functions like reproduction and metabolic regulation.

A nutritional strategy that stabilizes blood sugar and reduces inflammation can, in turn, soothe the adrenal response, allowing the rest of the hormonal orchestra to resume its intended rhythm.

Building Blocks for Biochemical Recalibration

Restoring hormonal equilibrium through nutrition involves a strategic focus on providing the body with the tools it needs for self-regulation. This process is grounded in several key principles:

- Sufficient Protein Intake ∞ Protein provides the essential amino acids necessary for producing peptide hormones, which include insulin and growth hormone. Adequate protein at each meal also promotes satiety and helps stabilize blood sugar, preventing the insulin spikes that can disrupt hormonal balance.

- Healthy Fats as Precursors ∞ Fats are not the enemy of hormonal health; they are a prerequisite. Steroid hormones are synthesized from cholesterol, which is derived from dietary fats. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, flaxseeds, and walnuts, are particularly important for creating flexible cell membranes that allow hormones to bind to their receptors effectively and for reducing the systemic inflammation that can dysregulate hormonal signaling.

- Fiber for Detoxification ∞ The body must not only produce hormones but also clear them once they have served their purpose. Fiber, particularly soluble fiber, plays a critical role in binding to excess estrogen in the digestive tract and ensuring its elimination. Without adequate fiber, estrogen can be reabsorbed into circulation, contributing to imbalances.

- Micronutrient Cofactors ∞ Vitamins and minerals act as the spark plugs for hormonal production. Zinc is essential for testosterone production and thyroid health. Selenium is required for the conversion of inactive thyroid hormone (T4) to its active form (T3). B vitamins and magnesium are crucial for supporting the adrenal glands and managing the body’s stress response. A deficiency in any of these key micronutrients can create a significant bottleneck in the hormonal production line.

By addressing these foundational nutritional requirements, you are not merely treating symptoms. You are providing the endocrine system with the necessary components to repair its communication pathways and restore its innate intelligence. This is the groundwork upon which lasting hormonal equilibrium is built.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational principles, we can examine the direct application of targeted nutritional strategies as a powerful adjunct to, and in some cases a preparatory step for, clinical hormonal protocols. The effectiveness of interventions like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or thyroid support is not determined in a vacuum.

The body’s underlying metabolic health, inflammatory status, and nutrient availability create the environment in which these therapies either succeed or struggle. A clinically informed nutritional approach can amplify the benefits of these protocols by ensuring the body is receptive and capable of utilizing these powerful signals correctly.

How Does Nutrition Influence Hormone Replacement Protocols?

When a patient begins a protocol such as weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate, the goal is to restore serum levels of the hormone to an optimal range. The body’s response to this therapy is deeply intertwined with its metabolic state.

For instance, a state of high inflammation and insulin resistance, often driven by a diet high in processed foods and sugar, can increase the activity of the enzyme aromatase. This enzyme converts testosterone into estrogen. In such a metabolic environment, a portion of the administered testosterone may be converted into estradiol, potentially leading to unwanted side effects and diminishing the intended therapeutic benefit.

A nutritional strategy focused on reducing inflammation and improving insulin sensitivity ∞ rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants from colorful vegetables, and low in refined carbohydrates ∞ can help modulate aromatase activity, ensuring the testosterone administered can perform its intended function.

Similarly, for a woman on a low-dose testosterone protocol for symptoms related to perimenopause, nutritional status is paramount. The body requires adequate levels of iron, B vitamins, and zinc to support energy pathways and red blood cell production, processes that are amplified by optimized testosterone levels. A nutrient-dense diet ensures that the introduction of testosterone is met with the necessary cofactors to translate hormonal signaling into tangible improvements in energy, mood, and vitality.

A well-formulated nutritional strategy acts as a force multiplier for clinical hormone therapies, optimizing the body’s internal environment for a better response.

The Central Role of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis is the command-and-control system for reproductive health in both men and women. The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones, in turn, signal the gonads (testes or ovaries) to produce testosterone or estrogen.

This entire cascade is highly sensitive to metabolic inputs. Nutritional deficiencies or metabolic stress can directly impair GnRH release from the hypothalamus, effectively silencing the entire downstream signaling chain. This is why chronic malnutrition or extreme dieting can lead to a loss of menstrual cycles in women or a functional hypogonadism in men.

Before initiating a protocol like TRT, which largely bypasses this axis, it is clinically prudent to first ensure the axis itself is not being suppressed by correctable nutritional factors.

The table below outlines key nutrients and their specific roles in supporting the HPG axis, illustrating how a targeted diet can provide the necessary support for this critical regulatory system.

| Nutrient | Role in HPG Axis Function | Primary Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Essential for the synthesis of GnRH in the hypothalamus and acts as a modulator of testosterone production in the testes. Deficiency is linked to impaired LH release. | Oysters, beef, pumpkin seeds, lentils |

| Vitamin D | Functions as a steroid hormone. Receptors are present in the hypothalamus, pituitary, and gonads. Correlated with healthy testosterone levels and ovarian function. | Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), fortified milk, sun exposure |

| Healthy Fats (Saturated and Monounsaturated) | Provide the cholesterol backbone for the synthesis of all steroid hormones, including testosterone and estrogen. Low-fat diets can suppress HPG axis function. | Avocado, olive oil, coconut oil, grass-fed butter, nuts |

| B Vitamins (especially B6 and Folate) | Involved in the clearance of excess estrogen through liver detoxification pathways and support dopamine production, which can influence prolactin levels and GnRH release. | Leafy greens, legumes, eggs, poultry, beef liver |

Nutritional Support for Thyroid and Adrenal Function

The thyroid and adrenal glands are deeply interconnected with the gonadal system. The body’s ability to convert the inactive thyroid hormone T4 into the active hormone T3 is a crucial step for metabolic health. This conversion process is dependent on several key nutrients, most notably selenium and zinc.

A diet lacking in these minerals can lead to a state of functional hypothyroidism, where serum T4 may be normal, but the body cannot produce enough active T3, resulting in symptoms of fatigue, weight gain, and low mood. Furthermore, chronic stress elevates cortisol, which can directly inhibit the T4-to-T3 conversion enzyme.

A nutritional protocol designed to restore hormonal equilibrium must therefore be multifaceted, supporting all interconnected systems simultaneously. This includes:

- Iodine and L-Tyrosine ∞ The direct building blocks of thyroid hormones. Found in seaweed, fish, and high-quality protein sources.

- Selenium and Zinc ∞ Essential cofactors for the T4 to T3 conversion enzyme. Brazil nuts are an excellent source of selenium, while zinc is abundant in shellfish and red meat.

- Adaptogenic Foods and Nutrients ∞ Certain foods and compounds can help modulate the body’s stress response. For example, phosphatidylserine (found in soy and white beans) and vitamin C can help buffer cortisol production, taking pressure off the adrenal glands.

By implementing these targeted nutritional strategies, an individual creates a biological foundation that is resilient and responsive. This approach can, in many cases, restore a significant degree of hormonal function on its own. When more advanced clinical protocols like peptide therapies (e.g. Sermorelin to support growth hormone) or TRT are deemed necessary, this nutritional groundwork ensures that the body is primed to receive and utilize these signals for maximum therapeutic benefit.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of hormonal equilibrium requires moving beyond the direct endocrine organs and into the complex, bidirectional communication systems that modulate their function. One of the most dynamic and clinically significant of these is the gut-hormone axis.

The trillions of microbes residing in the human gastrointestinal tract are not passive bystanders; they constitute a highly active metabolic organ that directly influences the fate of circulating hormones, particularly estrogens. The specific collection of gut microbes with genes capable of metabolizing estrogens is termed the estrobolome.

Dysregulation of the estrobolome is now understood to be a key factor in the pathophysiology of numerous hormone-dependent conditions, from polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) to endometriosis and even certain estrogen-receptor-positive cancers.

The Estrobolome and Enterohepatic Recirculation of Estrogen

Estrogens are primarily produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands, circulate through the body to exert their effects, and are ultimately metabolized by the liver. In the liver, they undergo a process called glucuronidation, where they are conjugated (packaged) to make them water-soluble and tagged for excretion.

These conjugated estrogens are then secreted into the bile, which flows into the gut. A healthy, balanced estrobolome allows these conjugated estrogens to pass through the intestines and be eliminated in the stool.

However, a dysbiotic estrobolome, characterized by an overgrowth of certain bacterial species, can produce high levels of an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme acts as a molecular pair of scissors, cleaving the glucuronide conjugate from the estrogen molecule. This deconjugation reverts the estrogen back into its active, unbound form.

This free estrogen can then be reabsorbed from the gut back into the bloodstream, a process known as enterohepatic recirculation. The result is an increase in the body’s total estrogen load, contributing to a state of estrogen dominance. This mechanism explains how a person’s diet and gut health can directly influence their hormonal status, independent of their ovarian production of estrogen.

The composition of the gut microbiome directly regulates circulating estrogen levels, functioning as a critical control point for hormonal homeostasis.

What Are the Clinical Implications of Estrobolome Dysbiosis?

The clinical consequences of elevated beta-glucuronidase activity and subsequent estrogen reabsorption are significant. Conditions associated with estrogen dominance can be initiated or exacerbated by this gut-driven mechanism. For example, in endometriosis, increased circulating estrogen can fuel the growth of ectopic endometrial tissue.

In the context of premenstrual syndrome (PMS), higher estrogen levels relative to progesterone in the luteal phase can worsen symptoms like bloating, irritability, and breast tenderness. This understanding provides a powerful therapeutic target. Nutritional interventions aimed at remodeling the gut microbiome can directly impact estrobolome function and, consequently, systemic hormonal balance.

The table below details specific bacterial genera and their documented influence on the estrobolome and estrogen metabolism, highlighting the complexity of this microbial ecosystem.

| Bacterial Genus | Influence on Estrogen Metabolism | Associated Health Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteroides | Some species are known producers of beta-glucuronidase, contributing to estrogen deconjugation and reabsorption. | Higher levels may be associated with increased estrogen recirculation and risk of estrogen-dominant conditions. |

| Lactobacillus | Generally considered protective. Certain strains can lower the pH of the gut, inhibiting the growth of beta-glucuronidase-producing pathogens. | Associated with a healthier estrobolome and more efficient estrogen excretion. Often depleted by antibiotic use. |

| Clostridium | Certain species, particularly within the Clostridia class, are potent producers of beta-glucuronidase. | Overgrowth is strongly linked to elevated beta-glucuronidase activity and increased enterohepatic circulation of estrogens. |

| Bifidobacterium | Considered beneficial for gut health. Helps maintain a healthy gut barrier and can compete with pathogenic bacteria, indirectly supporting healthy estrogen metabolism. | Supports overall gut homeostasis, which is foundational for a balanced estrobolome. |

Nutritional Modulation of the Estrobolome

The composition and activity of the estrobolome are highly malleable and respond directly to dietary inputs. This presents a significant opportunity for targeted nutritional intervention to restore hormonal equilibrium. Key strategies include:

- Increasing Dietary Fiber ∞ A high-fiber diet, rich in diverse prebiotics from sources like Jerusalem artichokes, garlic, onions, and asparagus, provides fuel for beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. These microbes ferment fiber into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, which lowers the colonic pH and helps maintain a healthy gut lining. This environment is less favorable for the growth of beta-glucuronidase-producing bacteria.

- Consumption of Cruciferous Vegetables ∞ Vegetables like broccoli, cauliflower, kale, and Brussels sprouts contain a compound called indole-3-carbinol (I3C). In the stomach, I3C is converted to diindolylmethane (DIM). DIM supports healthy estrogen metabolism in the liver, promoting the formation of less potent estrogen metabolites and supporting detoxification pathways that work in concert with the gut’s excretory function.

- Probiotic-Rich Fermented Foods ∞ The inclusion of fermented foods like sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, and unsweetened yogurt can introduce beneficial bacterial species, such as Lactobacillus, directly into the gut ecosystem, helping to restore a more favorable balance.

- Reducing Processed Foods and Alcohol ∞ A diet high in processed foods, sugar, and alcohol can promote gut dysbiosis, damage the intestinal lining, and place a heavy burden on the liver’s detoxification systems. Alcohol, in particular, has been shown to negatively impact the microbiome and increase circulating estrogen levels.

By focusing on the gut-hormone axis, we can appreciate that restoring hormonal equilibrium is a systems-level endeavor. It requires looking beyond the hormones themselves to the upstream factors that regulate their production, signaling, and, critically, their elimination. A nutritional protocol designed to cultivate a diverse and healthy microbiome is a powerful, evidence-based strategy for modulating the estrobolome and achieving lasting hormonal balance.

References

- Baker, J. M. Al-Nakkash, L. & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. (2017). Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas, 103, 45 ∞ 53.

- Jiang, I. Yong, P. J. Allaire, C. & Bedaiwy, M. A. (2021). Intricate Links between the Microbiome and Endometriosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(11), 5644.

- Yoo, J. Y. & Kim, S. S. (2020). The effects of dietary factors on the gut microbiome and colorectal cancer. Journal of Cancer Prevention, 25(3), 131 ∞ 142.

- Plottel, C. S. & Blaser, M. J. (2011). Microbiome and malignancy. Cell Host & Microbe, 10(4), 324 ∞ 335.

- Simopoulos, A. P. (2002). The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 56(8), 365 ∞ 379.

- Whittaker, J. & Wu, K. (2021). Low-fat diets and testosterone in men ∞ Systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 210, 105878.

- Badger, T. M. & Niyyati, M. (1983). Nutrition and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis. Grantome. Retrieved from https://grantome.com/grant/NIH/R01-HD017542-01

- Attia, Peter. Outlive ∞ The Science and Art of Longevity. Harmony, 2023.

- Mukherjee, Siddhartha. The Emperor of All Maladies ∞ A Biography of Cancer. Scribner, 2010.

- Ervin, S. M. Li, H. Lim, L. Roberts, L. R. & Redinbo, M. R. (2019). Gut microbiota and their contribution to estrogen-related cancers. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews, 38(4), 685 ∞ 701.

Reflection

Your Body’s Biological Narrative

The information presented here is a map, a detailed guide to the intricate biological landscape that governs your sense of well-being. It translates the often-confusing language of symptoms into the clear logic of systems, pathways, and molecules. The purpose of this knowledge is to shift your perspective.

The fatigue, the mood shifts, the metabolic frustrations ∞ these are not personal failings. They are signals from a highly intelligent system that is responding to its environment. Your body is telling a story, and you now have a better understanding of its grammar.

This understanding is the starting point for a new kind of conversation with your body. What signals is it sending you? How might the choices you make at the dinner table be influencing the messages relayed by your endocrine system? This journey of biochemical recalibration is deeply personal.

While the principles are universal, their application is unique to your individual physiology, genetics, and life circumstances. The path forward involves listening intently to your body’s feedback, observing the changes that occur with intention, and recognizing that you are an active participant in your own health. The potential to reclaim your vitality and function is encoded within your own biological systems, waiting for the right inputs to be unlocked.