Fundamentals

You may feel a persistent sense of fatigue that sleep does not seem to resolve. Perhaps you notice a subtle but unyielding shift in your body composition, or a change in your mood and mental clarity that you cannot quite attribute to any single cause.

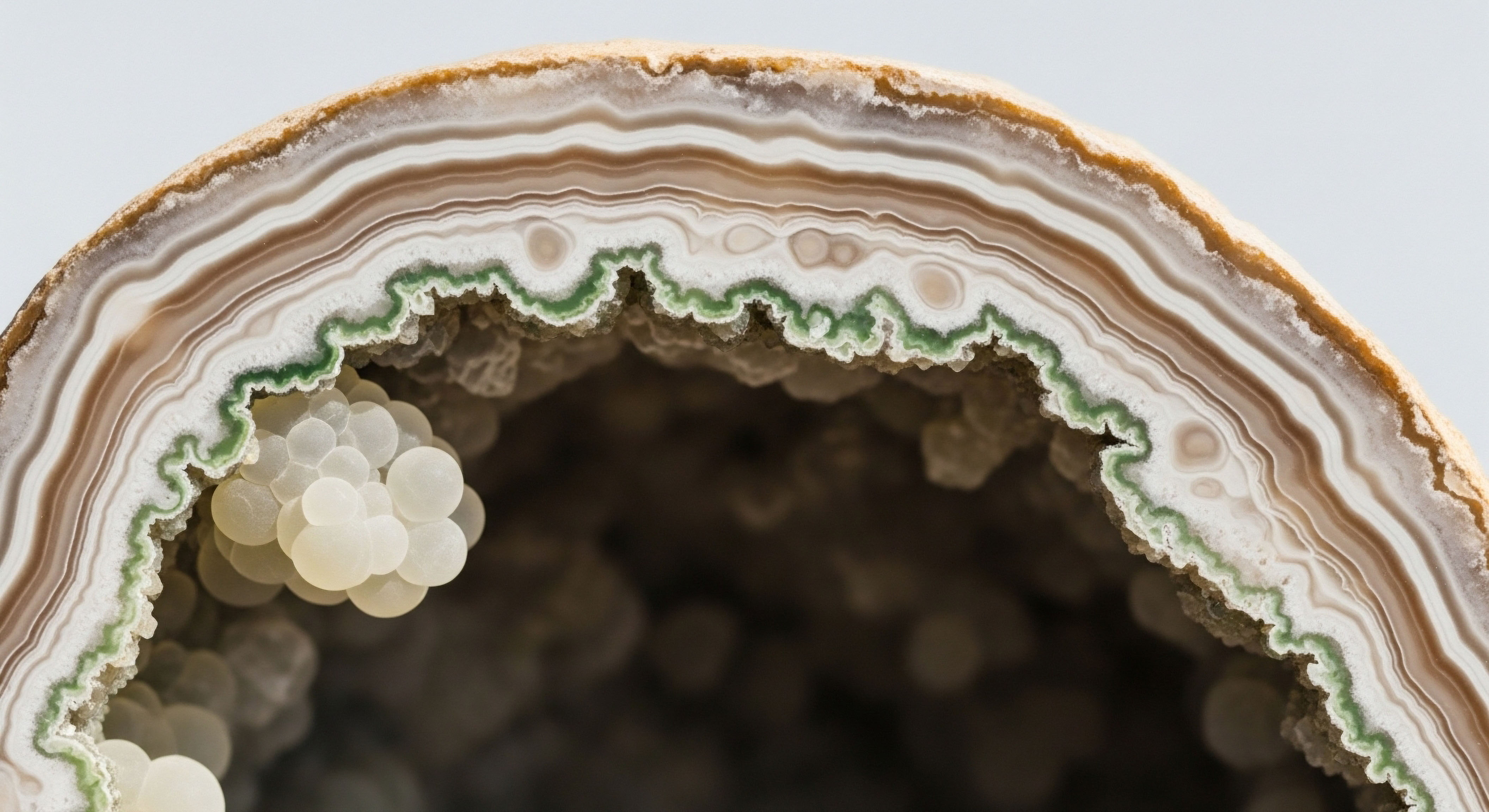

These experiences are valid and tangible signals from within your body. They often originate from the endocrine system, the intricate and intelligent network of glands that manufactures and secretes hormones. These hormones function as chemical messengers, orchestrating a silent, continuous conversation between trillions of cells to govern your metabolism, energy levels, stress response, and overall vitality. Understanding this system is the first step toward recalibrating your body’s internal environment.

Physical activity introduces a powerful and intentional stimulus to this finely tuned network. When you engage in exercise, you are initiating a cascade of hormonal responses. The pituitary gland, located at the base of the brain, releases human growth hormone, which is instrumental in repairing tissues and building muscle.

Your thyroid gland modulates metabolic rate, adjusting heart rate and body temperature to meet the demands of the activity. The adrenal glands produce cortisol and adrenaline, which mobilize energy stores and manage the body’s acute stress response to the physical exertion. Your pancreas adjusts insulin secretion to manage blood glucose, ensuring your muscles have the fuel they need. Each of these responses is a demonstration of your body’s remarkable ability to adapt.

Exercise acts as a primary form of communication with the endocrine system, prompting adaptive changes that regulate bodily functions.

The Body’s Internal Communication Grid

The endocrine system operates through a series of feedback loops, much like a sophisticated climate control system in a smart home. The hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain act as the central command, sensing the body’s needs and the levels of circulating hormones.

They send signals to peripheral glands like the adrenals, thyroid, and gonads, instructing them to increase or decrease their output. These peripheral glands, in turn, release hormones that travel through the bloodstream to target cells throughout the body, where they bind to specific receptors and deliver their instructions. The system then monitors the response, adjusting its own signals to maintain a state of dynamic equilibrium, or homeostasis.

Targeted exercise provides a predictable input into this system. The intensity, duration, and type of physical activity determine the specific hormonal “message” that is sent. A session of heavy resistance training sends a powerful signal for tissue growth and repair, while a long endurance run prompts adaptations related to fuel efficiency and cardiovascular function.

By applying these physical stressors in a structured way, you can guide the endocrine system toward favorable adaptations, enhancing its efficiency and resilience over time. This process is fundamental to how exercise shapes not only your physique but also your metabolic health and psychological well-being.

What Are the Key Hormonal Players in Exercise?

Several key hormones are directly and immediately influenced by physical activity. Understanding their roles provides a clearer picture of the conversation happening inside your body during and after a workout.

- Human Growth Hormone (HGH) ∞ Secreted by the pituitary gland, HGH plays a significant role in stimulating the growth, reproduction, and regeneration of cells. Exercise, particularly resistance training and high-intensity efforts, is a potent natural stimulus for HGH release, which aids in muscle repair and bone density.

- Testosterone ∞ While primarily associated with male physiology, testosterone is a vital anabolic hormone for both men and women, contributing to muscle mass, bone health, and libido. Vigorous exercise, especially weightlifting, has been shown to temporarily increase circulating testosterone levels.

- Cortisol ∞ Produced by the adrenal glands, cortisol is often called the “stress hormone.” During exercise, its release is a normal, adaptive response that helps mobilize glucose for energy and manage inflammation. Problems arise when cortisol levels are chronically elevated due to persistent stress without adequate recovery, a state that well-managed exercise can help regulate.

- Insulin ∞ Released by the pancreas, insulin’s primary job is to help cells absorb glucose from the bloodstream for energy. Regular physical activity dramatically improves insulin sensitivity, meaning the body needs to release less insulin to do the same job. This is a cornerstone of metabolic health.

- Catecholamines (Epinephrine and Norepinephrine) ∞ Commonly known as adrenaline and noradrenaline, these hormones are part of the “fight or flight” response. They increase heart rate, blood pressure, and energy supply during exercise, preparing the body for intense physical output.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational knowledge requires an appreciation for how different forms of exercise elicit distinct hormonal signatures. The type, intensity, and duration of your training regimen can be tailored to produce specific endocrine adaptations, allowing you to strategically influence your body’s hormonal milieu.

This targeted approach is central to using exercise as a sophisticated tool for optimizing health, body composition, and performance. The hormonal response is not a uniform reaction; it is a highly specific dialogue dictated by the nature of the physical stimulus applied.

For instance, the endocrine effects of a heavy, low-repetition strength training session are vastly different from those of a long, slow distance run. The former creates a significant anabolic signal, promoting the release of testosterone and growth hormone to repair and build muscle tissue.

The latter, conversely, excels at improving insulin sensitivity and enhancing the body’s capacity for fat oxidation, driven by different hormonal cascades. Understanding these distinctions allows for the creation of exercise protocols that are aligned with specific physiological goals, whether they are gaining muscle mass, improving metabolic flexibility, or reducing the physiological impact of chronic stress.

Crafting Hormonal Responses through Training Modalities

A well-designed wellness protocol uses different types of exercise to achieve complementary hormonal effects. Each modality has a unique impact on the endocrine system, and combining them thoughtfully can produce a more balanced and robust set of adaptations.

Resistance Training Anabolic Signaling

Resistance training is a powerful method for stimulating the secretion of anabolic hormones. The mechanical tension and metabolic stress induced by lifting weights trigger a potent response from the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis and the systems governing growth hormone.

Workouts that involve large muscle groups, moderate to heavy loads (70-85% of one-rep max), and relatively short rest intervals are particularly effective at maximizing this response. The acute increases in testosterone and HGH post-exercise create an internal environment conducive to protein synthesis, which is the cellular process of rebuilding and strengthening muscle fibers. This makes resistance training an indispensable tool for maintaining muscle mass, which is a critical factor for metabolic health throughout the lifespan.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) and Metabolic Recalibration

HIIT involves short bursts of near-maximal effort followed by brief recovery periods. This type of training imposes a significant, acute stress on the body, leading to a pronounced release of catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) and a substantial spike in growth hormone.

This intense stimulus also places a high demand on glucose metabolism, which in the long term leads to profound improvements in insulin sensitivity. Following a HIIT session, the body works to restore its physiological balance, a process that elevates metabolism for hours after the workout is complete. This post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC) contributes to greater energy expenditure and improved metabolic flexibility.

Targeted exercise protocols are designed to elicit specific hormonal responses, thereby steering physiological adaptations toward desired health outcomes.

The table below outlines the primary hormonal responses associated with different exercise modalities, offering a comparative view of how each training style communicates with the endocrine system.

| Exercise Modality | Primary Hormonal Response | Key Physiological Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Heavy Resistance Training |

Significant increase in Testosterone and Human Growth Hormone (HGH). |

Stimulation of muscle protein synthesis, increased muscle mass and bone density. |

| High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) |

Large spike in Catecholamines (Epinephrine) and HGH; improved post-exercise insulin action. |

Enhanced metabolic rate, improved insulin sensitivity, and greater cardiovascular efficiency. |

| Steady-State Endurance Training |

Improved insulin sensitivity, potential for cortisol regulation with appropriate intensity and duration. |

Increased mitochondrial density, enhanced fat oxidation, and better glucose management. |

| Mind-Body Practices (e.g. Yoga) |

Downregulation of baseline Cortisol levels; increased parasympathetic nervous system activity. |

Reduction of chronic stress markers, improved mood, and enhanced autonomic balance. |

How Does Overtraining Disrupt Endocrine Function?

There is a critical point where the volume and intensity of exercise can overwhelm the body’s adaptive capacity. This condition, often termed overtraining syndrome, represents a state of endocrine dysfunction. It occurs when the cumulative stress of training, combined with other life stressors, exceeds the body’s ability to recover.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the stress response, becomes dysregulated. This can manifest as either chronically elevated cortisol levels or, in later stages, an exhausted HPA axis with abnormally low cortisol output. Concurrently, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis can be suppressed, leading to reduced testosterone in men and menstrual irregularities in women.

Recognizing the signs of overtraining ∞ persistent fatigue, performance decline, mood disturbances, and sleep issues ∞ is vital for adjusting training protocols to allow for proper recovery and prevent long-term hormonal disruption.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of exercise-induced endocrine modulation requires a focus on the intricate signaling pathways and feedback mechanisms at the molecular level. The endocrine response to physical activity is governed by the precise interplay between exercise volume, intensity, and the individual’s physiological state.

This response is mediated through complex neuroendocrine axes, primarily the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Chronic adaptation to exercise involves a recalibration of these systems, leading to enhanced physiological resilience. However, excessive training stress can precipitate maladaptive states, providing a clear distinction between beneficial hormetic stress and detrimental chronic strain.

The magnitude of the hormonal response is directly proportional to the degree of homeostatic disruption caused by the exercise bout. For example, high-intensity resistance exercise creates significant metabolic and mechanical stress, activating signaling cascades that promote the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which in turn stimulates the pituitary to release luteinizing hormone (LH).

LH then acts on the Leydig cells in the testes to synthesize testosterone. This chain of events illustrates how a targeted physical stimulus can directly influence the HPG axis to produce a desired anabolic outcome. The efficiency of this signaling can be enhanced with consistent training, but it can also be blunted by inadequate nutrition or recovery.

Molecular Mechanisms of Exercise Induced Insulin Sensitivity

One of the most significant clinical outcomes of regular exercise is the marked improvement in insulin sensitivity. This adaptation is critical for the prevention and management of metabolic diseases. During exercise, muscle contractions stimulate the translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell membrane, a process that can occur independently of insulin signaling.

This provides an immediate pathway for glucose uptake by the working muscles. Following the exercise bout, insulin sensitivity is enhanced for a period of hours to days. This is mediated by the activation of key intracellular signaling proteins, most notably AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK functions as a cellular energy sensor.

When the ATP-to-AMP ratio drops during exercise, AMPK is activated, initiating a cascade that promotes fatty acid oxidation and further enhances GLUT4 translocation, thereby improving the muscle’s ability to respond to insulin and clear glucose from the blood.

The endocrine adaptations to chronic exercise are mediated by molecular recalibrations within the HPA and HPG axes, enhancing systemic resilience.

The following table provides a simplified overview of the cellular and hormonal responses to different training protocols, highlighting the specific mechanisms at play.

| Training Protocol | Key Cellular Mediator | Primary Hormonal Axis Affected | Long-Term Endocrine Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Resistance Training |

mTOR (mechanistic Target of Rapamycin) |

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis |

Increased androgen receptor sensitivity; enhanced pulsatile release of GH. |

| High-Intensity Interval Training |

AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) |

Sympathetic-Adrenal-Medullary (SAM) Axis |

Improved glycemic control via insulin-independent pathways; enhanced catecholamine response. |

| Prolonged Endurance Exercise |

PGC-1α (Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 alpha) |

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis |

Increased mitochondrial biogenesis; attenuated cortisol response to submaximal exercise. |

What Is the Endocrine Basis of the Overtraining Syndrome?

The overtraining syndrome (OTS) is a complex clinical condition characterized by a severe and persistent dysregulation of the neuroendocrine system. It represents the endpoint of a process where training and non-training stressors exceed an individual’s recovery capacity. From an endocrine perspective, OTS is often associated with a maladaptation of the HPA axis.

The “HPA axis exhaustion” hypothesis suggests that chronic, excessive stimulation leads to a desensitization of the pituitary and adrenal glands. This can result in a blunted or insufficient cortisol response to stressors, including exercise itself. This state, sometimes referred to as hypocortisolism, can explain many of the symptoms of OTS, such as profound fatigue, an inability to maintain training intensity, and an increased susceptibility to illness.

Simultaneously, the HPG axis is often suppressed in overtrained athletes. This is particularly evident in the “female athlete triad,” a syndrome involving low energy availability, menstrual dysfunction, and low bone mineral density. The physiological stress of excessive exercise combined with inadequate energy intake suppresses the pulsatile release of GnRH from the hypothalamus.

This, in turn, reduces the secretion of LH and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the pituitary, leading to low estrogen levels and amenorrhea. In male athletes, a similar suppression of the HPG axis can lead to a significant reduction in resting testosterone levels, a condition known as exercise-hypogonadal male condition (EHMC). These endocrine disruptions underscore the principle that exercise is a potent medicine, but the dose must be carefully managed to avoid toxicity.

References

- Kraemer, William J. and Nicholas A. Ratamess. “Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training.” Sports Medicine, vol. 35, no. 4, 2005, pp. 339-361.

- Hackney, A. C. “Exercise and the Regulation of Endocrine Hormones.” Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, vol. 135, 2015, pp. 293-311.

- Urhausen, A. and W. Kindermann. “Diagnosis of overtraining ∞ what tools do we have?” Sports Medicine, vol. 32, no. 2, 2002, pp. 95-102.

- Hill, E. E. et al. “Exercise and circulating cortisol levels ∞ the intensity threshold effect.” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 31, no. 7, 2008, pp. 587-591.

- Borer, Katarina T. Exercise Endocrinology. Human Kinetics, 2003.

- Vingren, J. L. et al. “Testosterone physiology in resistance exercise and training ∞ the up-stream regulatory elements.” Sports Medicine, vol. 40, no. 12, 2010, pp. 1037-1053.

- Goodyear, L. J. and B. B. Kahn. “Exercise, glucose transport, and insulin sensitivity.” Annual Review of Medicine, vol. 49, 1998, pp. 235-261.

- Cadegiani, F. A. and C. K. Kater. “Hormonal aspects of the overtraining syndrome ∞ a systematic review.” BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, vol. 9, no. 1, 2017, p. 14.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory, detailing how physical movement communicates with the deepest regulatory systems in your body. This knowledge shifts the perspective on exercise from a simple activity to a form of powerful biological conversation. Your body is constantly providing feedback through its signals of energy, recovery, mood, and sleep.

The true application of this science begins when you learn to listen to these signals with intent. Consider your own daily regimen not as a task to be completed, but as a series of inputs. What is your body communicating back to you in the hours and days after different types of physical effort?

Recognizing these patterns is the foundational step in crafting a truly personalized protocol, one that aligns with your unique physiology and moves you consistently toward a state of greater vitality and function.