Fundamentals

You feel it, don’t you? That persistent, low-grade hum of being perpetually switched ‘on.’ It’s the feeling of being stretched thin, of your internal battery never quite reaching a full charge. You might describe it as fatigue, brain fog, or a general sense of being out of sync with your own body.

This experience, this lived reality for so many of us, is a direct conversation your body is having with you. It is a biological signal, and your hormones are the language it is speaking. Understanding this language is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

The question of whether we can consciously influence our hormonal health through something as accessible as stress management is a profound one. The answer lies deep within our own physiology, in the intricate and elegant communication network that governs our very being ∞ the endocrine system.

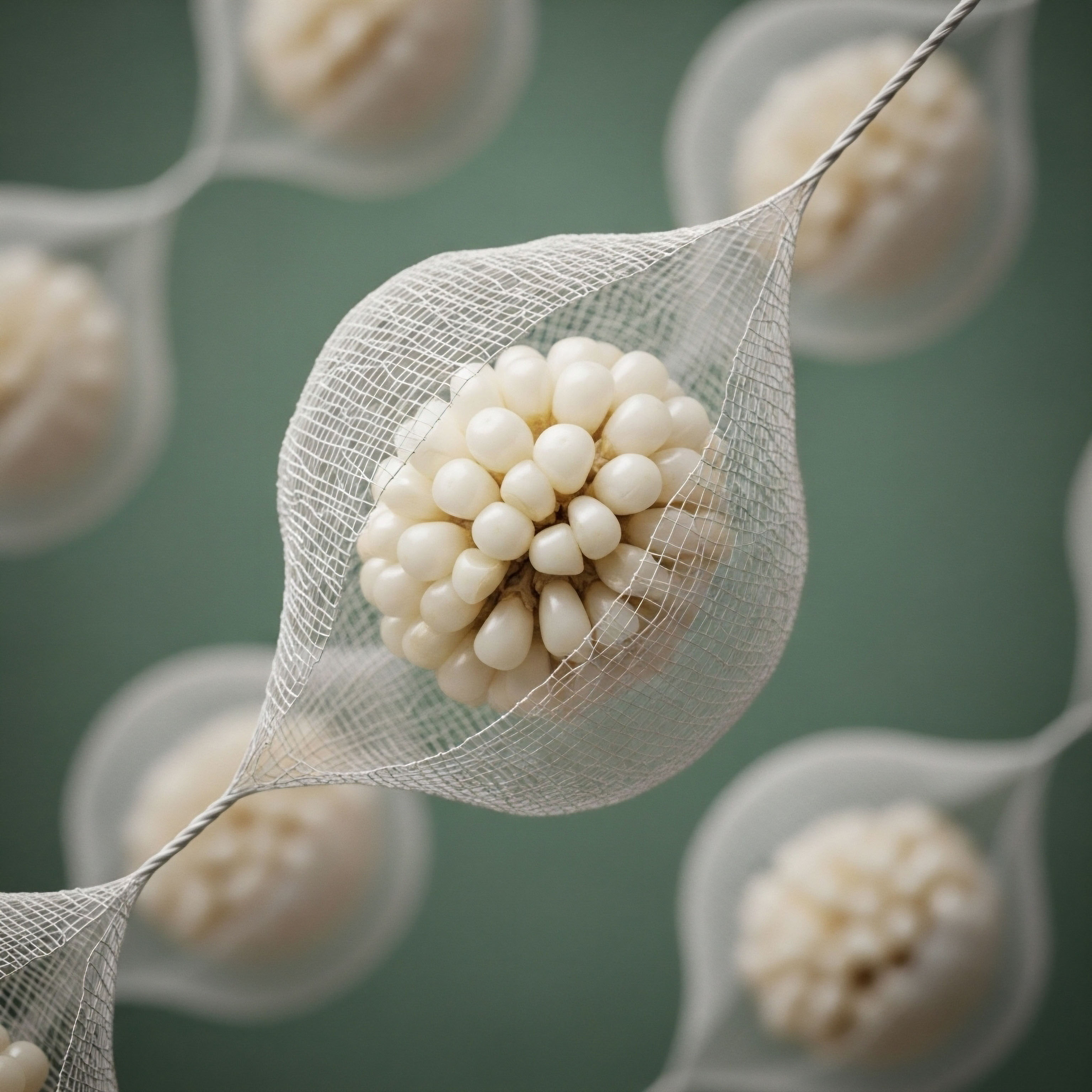

Think of your endocrine system as the body’s internal postal service, a sophisticated network of glands that produce and dispatch chemical messengers called hormones. These messengers travel through your bloodstream, delivering precise instructions to every cell, tissue, and organ. They dictate your energy levels, your mood, your metabolism, your sleep cycles, and, of course, your reproductive health.

This system is designed for exquisite balance, a state of dynamic equilibrium known as homeostasis. When this balance is maintained, you feel vibrant, resilient, and fully functional. When it is disrupted, you experience the symptoms that so many of us have come to accept as a normal part of modern life.

Your body’s hormonal system is a finely tuned orchestra, and chronic stress can cause key instruments to fall out of harmony.

The Two Sides of the Hormonal Coin the HPA and HPG Axes

To understand how stress directly impacts your sex hormones, we need to introduce two critical components of your endocrine system ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. These are two distinct, yet interconnected, command chains that originate in the brain and extend throughout the body. They represent the two fundamental priorities of any biological organism ∞ survival and reproduction.

The HPA axis is your body’s primary stress response system. Imagine it as your internal emergency broadcast network. When your brain perceives a threat ∞ be it a physical danger, an emotional upset, or a demanding work deadline ∞ the hypothalamus (the command center in your brain) sends a signal to the pituitary gland, which in turn signals the adrenal glands (located on top of your kidneys) to release a cascade of stress hormones.

The most prominent of these is cortisol. In the short term, cortisol is incredibly useful. It sharpens your focus, mobilizes energy stores, and prepares your body for immediate action. It is the biological equivalent of pulling the fire alarm; it gets everyone’s attention and prioritizes immediate survival.

The HPG axis, on the other hand, is your body’s system for regulating reproductive function and producing sex hormones. This includes testosterone in men and estrogen and progesterone in women. Think of the HPG axis as the body’s long-term investment and planning department.

It governs functions that are essential for the continuation of the species, such as fertility, libido, and the maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics. These functions are resource-intensive and are prioritized when the body feels safe, nourished, and secure.

When Wires Get Crossed the Impact of Chronic Stress

Here is where the connection becomes clear. The body’s resources are finite. It cannot be in a state of high alert and a state of long-term investment simultaneously. When the HPA axis is chronically activated, when the fire alarm is ringing day in and day out, the body makes a crucial metabolic decision.

It diverts resources away from the long-term projects of the HPG axis to fuel the continuous, perceived emergency. This is not a design flaw; it is a brilliant survival mechanism. Your body is essentially saying, “We can’t worry about building for the future right now; we need all hands on deck to deal with the present crisis.”

This diversion of resources has a direct, measurable impact on your sex hormone production. Elevated levels of cortisol can send inhibitory signals back to the brain, effectively telling the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to downregulate the HPG axis.

This can lead to a reduction in the production of key signaling hormones like Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), Luteinizing Hormone (LH), and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), which are the very messengers that instruct the gonads (testes and ovaries) to produce sex hormones. The result is a decline in testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone levels. This is the biological reality behind feeling depleted, experiencing low libido, or noticing changes in your menstrual cycle during periods of high stress.

Reclaiming Control the Promise of Stress Management

The beautiful and empowering aspect of this entire system is that it is not a one-way street. Just as your body can downregulate hormonal pathways in response to stress, it can also upregulate them in response to safety and relaxation. Stress management techniques are not simply about feeling calmer; they are a direct form of biological intervention.

They are a way of communicating with your nervous system and, by extension, your endocrine system, telling it that the perceived threat has passed and that it is safe to reinvest in long-term health and vitality.

Practices like mindfulness meditation, deep diaphragmatic breathing, and gentle movement therapies like yoga are powerful tools for deactivating the HPA axis. They work by stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system, the “rest and digest” counterpart to the “fight or flight” sympathetic nervous system.

When you engage in these practices, you are actively lowering your cortisol levels and creating the physiological space for your HPG axis to come back online. You are, in a very real sense, recalibrating your internal communication network, shifting the priority from short-term survival to long-term thriving.

This is the foundational principle upon which the entire practice of personalized wellness is built ∞ the understanding that our thoughts, our behaviors, and our internal state have a direct and profound impact on our biological function.

Intermediate

Having established the foundational connection between the body’s stress and reproductive axes, we can now examine the specific biochemical mechanisms through which this interplay unfolds. The feeling of being “stressed out” is not just an emotional state; it is a cascade of precise, measurable physiological events that directly alter the production of your sex hormones.

Understanding these pathways provides a clear rationale for why stress management techniques are not merely palliative but are, in fact, a form of targeted hormonal therapy. They are a means of consciously regulating the very systems that determine your energy, vitality, and reproductive health.

The Central Command and Its Suppression

The entire process of sex hormone production begins in the brain with Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus act as the master pulse generator for the reproductive system. They release GnRH in a rhythmic, pulsatile fashion, and this rhythm is critical for proper function.

These pulses of GnRH travel to the pituitary gland and signal it to release two other key hormones ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). LH and FSH then travel through the bloodstream to the gonads ∞ the testes in men and the ovaries in women ∞ where they provide the final instruction to produce testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone.

Chronic stress throws a wrench into this elegant system. The primary mechanism of disruption is the sustained elevation of cortisol, the body’s main glucocorticoid stress hormone. Cortisol, and the signaling molecules that trigger its release, can suppress the HPG axis at multiple levels:

- At the Hypothalamus ∞ Cortisol can directly inhibit the GnRH neurons, slowing down or disrupting their pulsatile firing rate. This is like turning down the volume on the master signal. The instructions for hormone production become weaker and less frequent.

- At the Pituitary ∞ Elevated cortisol can also make the pituitary gland less sensitive to the GnRH signal. Even if some GnRH is released, the pituitary doesn’t respond as robustly, leading to reduced secretion of LH and FSH.

- At the Gonads ∞ There is evidence to suggest that stress hormones can even have a direct inhibitory effect on the testes and ovaries, making them less responsive to the signals from LH and FSH.

This multi-level suppression ensures that in times of perceived chronic danger, the body’s significant energy investment in reproductive functions is put on hold. The clinical consequences are direct ∞ in men, this can manifest as low testosterone (hypogonadism) with symptoms like fatigue, low libido, and loss of muscle mass. In women, it can lead to irregular menstrual cycles, anovulation (the absence of ovulation), and worsening of perimenopausal symptoms.

Stress management techniques work by down-regulating the body’s sympathetic nervous system, thereby reducing cortisol and allowing the reproductive hormonal axis to function optimally.

The Cortisol-Testosterone Seesaw a Detailed Look

The inverse relationship between cortisol and testosterone is one of the most well-documented phenomena in endocrinology. When cortisol is high, testosterone tends to be low, and vice versa. This is a direct consequence of the HPA axis’s dominance over the HPG axis during periods of stress.

Consider the following table, which outlines the direct mechanisms of cortisol-induced testosterone suppression:

| Mechanism of Suppression | Physiological Explanation | Clinical Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of GnRH Release | Cortisol acts on the hypothalamus to reduce the frequency and amplitude of GnRH pulses. | Reduced signaling to the pituitary, leading to lower LH and FSH release. |

| Reduced Pituitary Sensitivity | The pituitary gland becomes less responsive to GnRH, further decreasing LH output. | Lower levels of LH in the bloodstream, the primary signal for testosterone production. |

| Direct Testicular Inhibition | Cortisol can directly interfere with the function of the Leydig cells in the testes, which are responsible for producing testosterone. | Even with adequate LH signaling, the testes may produce less testosterone. |

| Increased Aromatase Activity | Some evidence suggests that high cortisol levels can increase the activity of the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone into estrogen. | A double blow to hormonal balance ∞ lower testosterone and potentially higher estrogen levels in men. |

This intricate biochemical relationship underscores why chronic stress is so detrimental to male hormonal health. It’s not just a vague feeling of being unwell; it’s a systematic dismantling of the very hormonal architecture that supports masculine vitality.

How Do We Quantify the Impact of Stress Management Interventions?

The efficacy of stress management techniques in altering these pathways is not just theoretical. It can be measured through clinical research. Studies examining the neuroendocrine effects of practices like mindfulness meditation have demonstrated tangible changes in the body’s hormonal and neurotransmitter systems.

Here are some of the key findings:

- Cortisol Reduction ∞ Regular meditation practice has been shown to significantly lower baseline cortisol levels and dampen the cortisol response to acute stressors. This is perhaps the most direct way these techniques support hormonal health.

- Neurotransmitter Modulation ∞ Meditation can increase levels of calming neurotransmitters like GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) and mood-stabilizing neurotransmitters like serotonin. These changes in brain chemistry contribute to a greater sense of well-being and a reduced perception of stress, which in turn helps to regulate the HPA axis.

- Improved Autonomic Balance ∞ Stress management practices enhance the activity of the parasympathetic nervous system, promoting a state of relaxation. This is often measured by an increase in heart rate variability (HRV), a key indicator of autonomic nervous system resilience and flexibility.

By engaging in these practices, an individual is not just managing their mental state; they are actively participating in the regulation of their own endocrine system. They are creating a biological environment that is conducive to optimal hormonal function. This is the bridge between our internal experience and our physiological reality, and it is a bridge we can learn to cross with intention and skill.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of the interplay between stress and sex hormone production requires moving beyond simplified models and into the nuanced world of molecular endocrinology and systems biology. While the inverse relationship between the HPA and HPG axes is a cornerstone of this field, the precise molecular pathways and feedback loops involved are areas of ongoing, intensive research.

This deeper exploration reveals a complex network of signaling molecules, receptor interactions, and genetic expression changes that collectively orchestrate the body’s integrated response to stress. It also allows us to critically evaluate popular concepts and appreciate the true complexity of hormonal regulation.

Deconstructing the Pregnenolone Steal Hypothesis

Within functional and integrative medicine, the “pregnenolone steal” hypothesis has been a popular and conceptually simple model to explain how chronic stress depletes sex hormones. The theory posits that since all steroid hormones, including cortisol and sex hormones, are derived from a common precursor molecule, pregnenolone, the high demand for cortisol production during stress “steals” this precursor away from the pathways that produce DHEA, testosterone, and estrogen. While this provides a tidy narrative, it is a significant oversimplification of adrenal and gonadal physiology.

A more accurate, evidence-based understanding reveals several critical flaws in this model:

- Compartmentalization of Steroidogenesis ∞ The adrenal cortex is not a single, homogenous factory. It is divided into distinct zones, each with a specific enzymatic machinery. Cortisol is primarily synthesized in the zona fasciculata, while adrenal androgens like DHEA are produced in the zona reticularis. These zones function as separate compartments. There is no known mechanism for one zone to “steal” pregnenolone from another. Hormone production is regulated locally within the cell, based on the specific enzymes present and the external signals received (like ACTH).

- Regulation by Enzymes ∞ The flux of precursors down a specific steroidogenic pathway is determined by the activity of key enzymes. For example, the decision to produce cortisol versus DHEA is largely controlled by the presence and activity of enzymes like 17α-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase. Chronic stress and aging can alter the expression and activity of these enzymes, which is a more accurate explanation for the observed decline in DHEA levels than a simple “stealing” of substrate.

- The True Mechanism of Suppression ∞ As detailed previously, the primary mechanism by which stress suppresses sex hormones is not at the level of substrate availability in the adrenal gland, but through central nervous system inhibition of the HPG axis. The brain, responding to high levels of glucocorticoids and other stress signals, actively downregulates the entire reproductive cascade starting with GnRH. This central suppression is a far more potent and physiologically significant mechanism than any hypothetical competition for pregnenolone.

Why does this distinction matter? Because a precise understanding of the mechanism allows for more targeted and effective interventions. It shifts the focus from attempting to supplement with precursor hormones (which may be ineffective if the central signaling is suppressed) to addressing the root cause ∞ the chronic activation of the stress response itself.

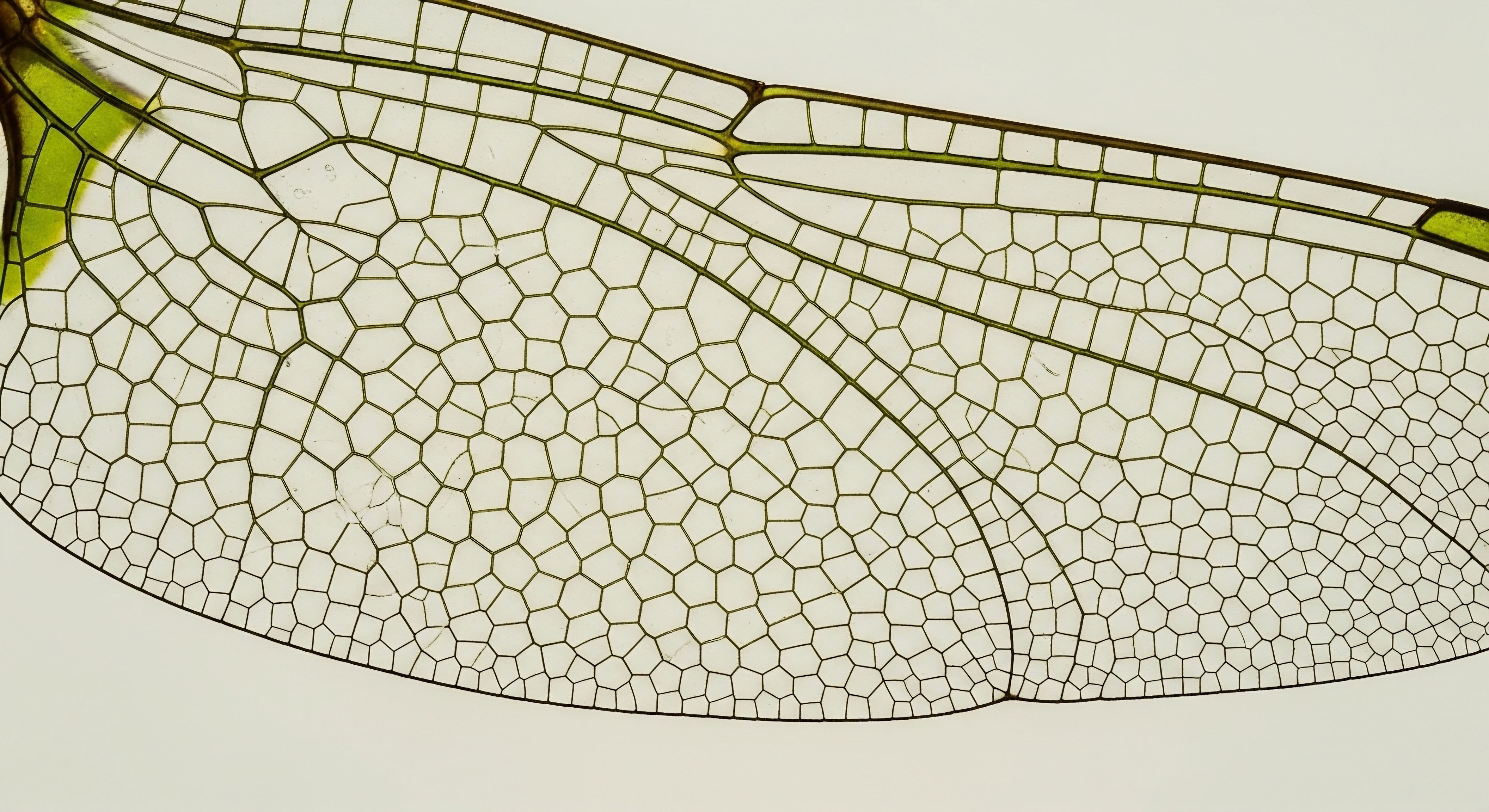

The body’s response to stress is a complex symphony of neural, endocrine, and immune signals, and understanding this interplay is key to effective intervention.

Beyond Cortisol Other Mediators of Stress-Induced Reproductive Suppression

While cortisol is a major player, it is not the sole mediator of stress’s effects on the HPG axis. A growing body of research highlights the role of other neuropeptides and signaling molecules that are released during the stress response. Two particularly important examples are Gonadotropin-Inhibitory Hormone (GnIH) and Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP).

Gonadotropin-Inhibitory Hormone (GnIH)

GnIH, also known as RFamide-related peptide-3 (RFRP-3) in mammals, is a neuropeptide that, as its name suggests, has a direct inhibitory effect on the reproductive axis. GnIH neurons are found in the hypothalamus and project to GnRH neurons. When activated, GnIH can directly suppress the activity of GnRH neurons, reducing the release of GnRH.

Crucially, research has shown that both psychological and immune stressors increase the expression and activity of GnIH. Furthermore, GnIH neurons express glucocorticoid receptors, providing a direct link between the HPA axis and this inhibitory pathway. This suggests that cortisol may exert some of its suppressive effects on the HPG axis by stimulating the GnIH system.

Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP)

CGRP is a neuropeptide that is widely distributed in the central and peripheral nervous systems and is involved in a variety of stress responses. Research has demonstrated that central administration of CGRP can potently suppress LH pulses.

Interestingly, this suppressive effect appears to be mediated through the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) system, as the effect can be blocked by a CRH receptor antagonist. This indicates a complex interplay between different stress signaling systems, where CGRP may act upstream of CRH to inhibit the HPG axis. These findings illustrate that the body has multiple, redundant pathways to ensure that reproductive function is suppressed during times of significant stress.

The Neuro-Endocrine-Immune Axis and Inflammation

A truly comprehensive view of stress must also incorporate the immune system. The neuro-endocrine-immune axis is a complex, bidirectional communication network. Chronic psychological stress is a potent activator of the innate immune system, leading to a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. This is characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α).

These inflammatory cytokines are not just passive bystanders; they can also act as signaling molecules within the central nervous system and can directly suppress the HPG axis. For example, elevated IL-6 has been shown to inhibit GnRH secretion. Therefore, the pathway from chronic stress to hormonal dysregulation can be viewed as follows:

- Chronic Stress Perception ∞ Activates the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system.

- Hormonal and Immune Response ∞ Leads to sustained high levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.

- Multi-level HPG Suppression ∞ Cortisol, GnIH, CGRP, and inflammatory cytokines all contribute to the suppression of the GnRH pulse generator, leading to reduced sex hormone production.

This integrated, systems-biology perspective reveals why stress management techniques that have anti-inflammatory effects, such as meditation and yoga, can be so beneficial for hormonal health. They are not just reducing cortisol; they are also dampening the chronic inflammatory response, thereby addressing another critical pathway of HPG axis suppression.

The following table summarizes the key molecular mediators and their effects:

| Mediator | Source | Effect on HPG Axis | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | Adrenal Cortex | Inhibitory | Suppresses GnRH and pituitary sensitivity. |

| GnIH (RFRP-3) | Hypothalamus | Inhibitory | Directly inhibits GnRH neuron activity. |

| CGRP | Central Nervous System | Inhibitory | Acts via the CRH system to suppress LH pulses. |

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines (e.g. IL-6) | Immune Cells | Inhibitory | Can directly suppress GnRH secretion. |

This level of detailed understanding moves us beyond simplistic models and into a more accurate and clinically useful framework. It affirms that stress management is a powerful modality for influencing health, not through some vague, undefined mechanism, but by directly and measurably altering the complex web of neural, endocrine, and immune signals that govern our physiology.

References

- Rivier, C. and S. Rivest. “Effect of stress on the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis ∞ peripheral and central mechanisms.” Biology of reproduction 45.4 (1991) ∞ 523-532.

- Whirledge, S. and J. A. Cidlowski. “Glucocorticoids, stress, and reproduction ∞ the good, the bad, and the unknown.” Endocrinology 151.3 (2010) ∞ 904-910.

- Kauffman, A. S. “Neural and endocrine mechanisms underlying stress-induced suppression of pulsatile LH secretion.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 498 (2019) ∞ 110579.

- Guilliams, T. G. and L. E. Edwards. “Chronic stress and the HPA axis ∞ Clinical assessment and therapeutic considerations.” The Standard 9.2 (2010) ∞ 1-12.

- Kirby, E. D. et al. “Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone is a key regulator of the reproductive axis in the Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus).” Endocrinology 150.9 (2009) ∞ 4166-4176.

- Pace, T. W. et al. “Effect of compassion meditation on neuroendocrine, innate immune and behavioral responses to psychosocial stress.” Psychoneuroendocrinology 34.1 (2009) ∞ 87-98.

- Bambino, T. H. and A. J. Hsueh. “Direct inhibitory effect of glucocorticoids upon testicular luteinizing hormone receptor and steroidogenesis in vivo and in vitro.” Endocrinology 108.6 (1981) ∞ 2142-2148.

- Pascoe, L. et al. “The effects of meditation on the neuro-immuno-endocrine axis ∞ A narrative review.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 10.21 (2021) ∞ 5078.

- Saleh, R. et al. “Stress, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, and aggression.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 141 (2022) ∞ 104838.

- Tsigos, C. and G. P. Chrousos. “Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress.” Journal of psychosomatic research 53.4 (2002) ∞ 865-871.

Reflection

You have journeyed through the intricate biological landscape that connects your internal state to your hormonal vitality. You have seen how the whispers of stress can become a roar that silences the delicate hormonal conversations essential for your well-being. This knowledge is more than just information; it is a map.

It is a map that shows you the pathways, the connections, and the levers that you can access. The journey of understanding your own body is deeply personal, and it unfolds one step at a time. The information presented here is a foundational piece, a starting point for a more profound inquiry into your own unique physiology.

Consider your own life, your own patterns of stress, and your own experiences of vitality or depletion. How might these pathways be playing out within you? What small, intentional shifts could you make to begin communicating a message of safety and balance to your nervous system?

The power of this knowledge lies not in its complexity, but in its application. The path to hormonal optimization is one of partnership with your own body, a process of listening to its signals and responding with intention and care. This understanding is the first, most crucial step on that path. What will your next step be?