Fundamentals

You are here because you are asking a vital question, one that connects your internal state of being with one of life’s most profound biological processes. The feeling of pressure, the weight of expectation, and the persistent hum of daily stress are not just experiences contained within your mind.

They are biochemical signals that ripple through your entire physiology. Your body is a meticulously interconnected system, and the pathways that govern your stress response are deeply intertwined with the ones that regulate your reproductive health. Understanding this connection is the first step toward reclaiming agency over your fertility outcomes.

The Body’s Unified Operating System

Your body operates under a principle of resource allocation. It possesses a central command system designed to ensure survival above all else. This system, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, is your primary stress response mechanism. When you perceive a threat ∞ be it a looming work deadline, financial pressure, or the emotional strain of trying to conceive ∞ the HPA axis is activated.

This activation culminates in the release of cortisol, the body’s principal stress hormone. Cortisol is a powerful metabolic agent, designed to mobilize energy reserves and sharpen focus for immediate survival.

Simultaneously, your body runs a parallel program for procreation, governed by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This pathway regulates the production of key reproductive hormones, most notably testosterone in men. Testosterone is the foundational hormone for spermatogenesis, the process of creating mature sperm. The HPA and HPG axes are in constant communication.

When the body is in a state of chronic stress, it interprets the environment as unsafe or resource-scarce. Consequently, it makes a logical, albeit frustrating, decision ∞ it diverts resources away from long-term projects like reproduction to fund the immediate needs of survival. Elevated cortisol levels send a direct signal to the HPG axis to downshift its activity.

Chronic stress instructs the body to prioritize immediate survival, systematically de-prioritizing the complex biological process of reproduction.

Cortisol’s Effect on Male Hormones

The relationship between cortisol and testosterone is one of biological competition. High circulating levels of cortisol can directly suppress the signaling required for testosterone production. This occurs at multiple levels of the HPG axis, starting in the brain. The result is a diminished hormonal drive for the testes to perform their essential functions.

Lower testosterone levels can lead to a reduction in both the quantity and quality of sperm produced. This is not a malfunction; it is the body’s adaptive response to a perceived state of emergency. The system is functioning as designed, even if the outcome is undesirable in the context of modern life where stressors are often psychological rather than physical threats to life.

What Is Oxidative Stress?

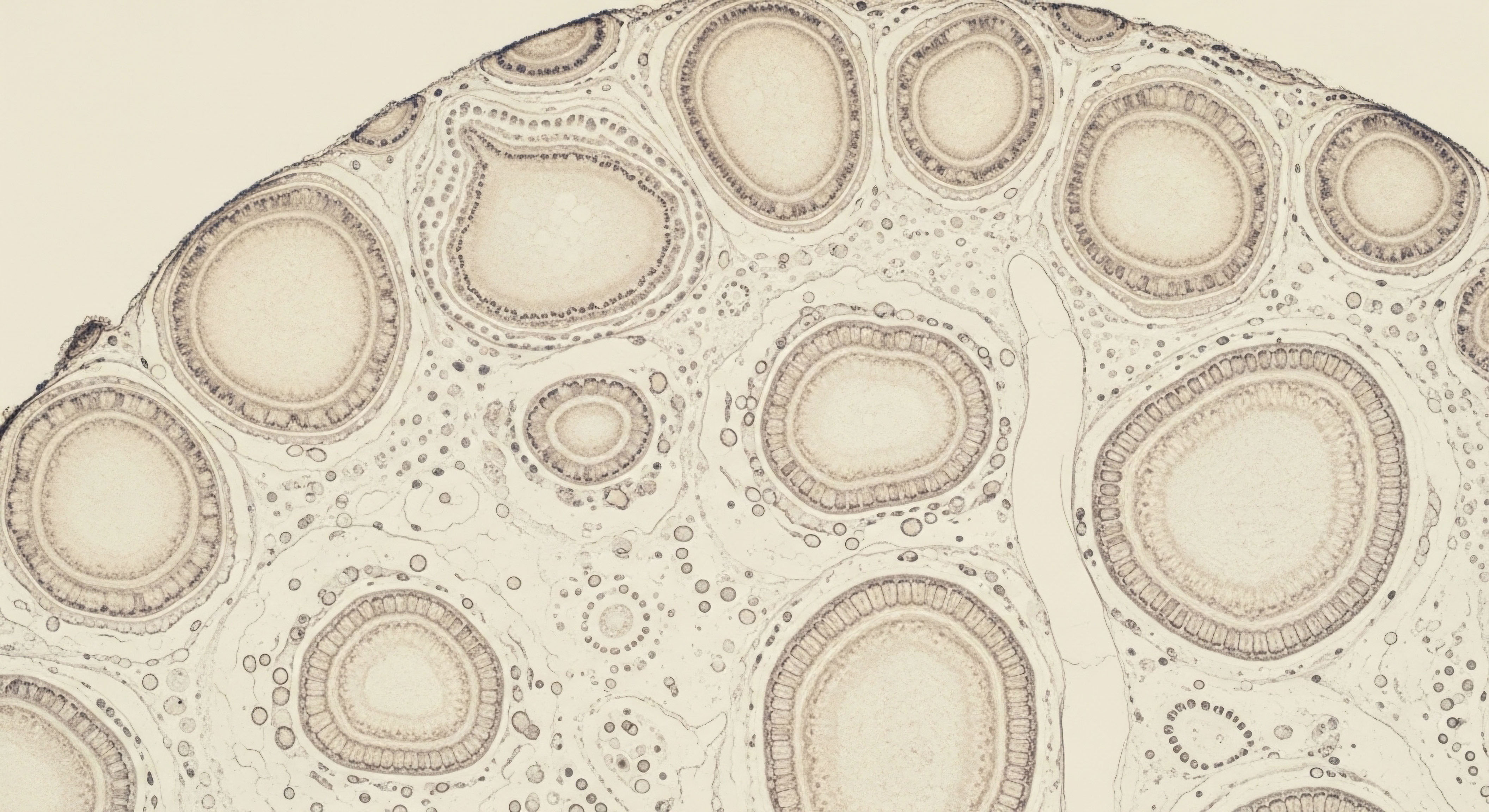

Beyond the direct hormonal suppression, chronic psychological stress contributes to a damaging cellular state known as oxidative stress. This condition represents an imbalance between the production of highly reactive molecules called free radicals (or Reactive Oxygen Species, ROS) and the body’s ability to neutralize them with antioxidants.

Sperm cells are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress. Their cell membranes are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are easily damaged by ROS. This damage can impair the sperm’s motility, making it difficult for them to travel to the egg, and can also harm the precious genetic material contained within the sperm head. Oxidative stress is a key mechanism through which the abstract experience of “stress” translates into tangible, cellular-level damage affecting fertility.

Therefore, the question of whether stress management can improve fertility is a question of biology. By managing stress, you are not merely seeking a calmer state of mind. You are actively intervening in these physiological processes, aiming to lower cortisol, reduce oxidative damage, and restore the hormonal balance necessary for optimal reproductive function.

Intermediate

To appreciate how stress management techniques can yield tangible improvements in male fertility, we must examine the precise biochemical conversations happening within the body. The link between your psychological state and your seminal parameters is not abstract.

It is a concrete sequence of endocrine events, a cascade of signals that can be either disrupted by stress or supported by targeted relaxation and lifestyle interventions. Moving beyond the fundamental concepts, we can map the direct lines of communication from the brain to the testes and identify the specific points where stress intervenes.

The Endocrine Cascade from Stress to Suppression

The body’s hormonal systems are organized hierarchically. The hypothalamus, a small region in the brain, acts as the master regulator. In the context of reproduction, it secretes Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in a pulsatile rhythm. This pulse is a critical instruction for the pituitary gland, which responds by releasing two other key hormones ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins travel through the bloodstream to the testes, where they deliver their specific orders:

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH) acts on the Leydig cells in the testes, instructing them to produce testosterone. Consistent LH signaling is essential for maintaining healthy testosterone levels.

- Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) acts on the Sertoli cells, which are the “nurse” cells of the testes. FSH is crucial for supporting the complex process of spermatogenesis, the maturation of sperm cells.

Chronic stress disrupts this entire chain of command. Elevated cortisol, produced by the HPA axis, has a direct inhibitory effect on the hypothalamus, suppressing the release of GnRH. A weaker or less frequent GnRH pulse leads to diminished LH and FSH secretion from the pituitary. The downstream effect is reduced testosterone production and impaired support for spermatogenesis. The system is throttled at its source.

| Step | Regulating Gland/Organ | Hormone/Signal | Function in Fertility | Impact of Chronic Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hypothalamus | GnRH Pulse | Initiates the reproductive cascade. | Suppressed by high cortisol, leading to weaker signaling. |

| 2 | Pituitary Gland | LH and FSH | Stimulate the testes. | Reduced secretion due to lower GnRH signal. |

| 3 | Testes (Leydig Cells) | Testosterone | Drives libido and spermatogenesis. | Production is decreased due to lower LH stimulation. |

| 4 | Testes (Sertoli Cells) | Spermatogenesis Support | Nourishes developing sperm. | Process is impaired due to lower FSH and testosterone. |

How Can Stress Management Techniques Reverse This?

Stress management protocols are, in essence, clinical interventions designed to downregulate the HPA axis and restore autonomic nervous system balance. By reducing the “threat” signal, these techniques lower the demand for cortisol production, allowing the HPG axis to resume its normal function. Different techniques work through distinct but complementary physiological mechanisms.

Targeted stress management techniques function as a biological reset, calming the body’s alarm system to restore the hormonal environment required for fertility.

For instance, practices like mindfulness meditation and deep diaphragmatic breathing activate the parasympathetic nervous system, the body’s “rest and digest” network. This activation acts as a direct counterbalance to the sympathetic “fight or flight” response that drives stress. Regular practice can lower baseline cortisol levels, reduce blood pressure, and improve heart rate variability, all markers of a less-strained system.

Similarly, moderate physical activity is a well-documented method for metabolizing excess stress hormones and boosting endorphins, which have a mood-elevating and stress-reducing effect. However, it is a matter of finding the right balance, as excessive, high-intensity exercise can itself become a physical stressor that elevates cortisol.

| Technique | Primary Mechanism of Action | Physiological Outcome | Recommended Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) | Reduces rumination and emotional reactivity; activates the parasympathetic nervous system. | Lowered perceived stress and cortisol levels; improved emotional regulation. | 8-week structured program; daily 20-45 minute guided meditations. |

| Diaphragmatic Breathing | Stimulates the vagus nerve, a key component of the parasympathetic nervous system. | Immediate reduction in heart rate and blood pressure; calms the nervous system. | 5-10 minutes of slow, deep belly breathing, 1-2 times daily or during acute stress. |

| Moderate Physical Exercise | Metabolizes stress hormones (cortisol, adrenaline); releases endorphins. | Improved mood, better sleep quality, and potentially enhanced testosterone levels. | 30-45 minutes of moderate-intensity activity (brisk walking, swimming, cycling) 3-5 times per week. |

| Optimized Sleep Hygiene | Facilitates hormonal regulation, cellular repair, and glymphatic clearance in the brain. | Lowered morning cortisol; optimized testosterone and growth hormone release. | 7-9 hours of consistent, high-quality sleep per night; cool, dark, quiet environment. |

By engaging in these practices, an individual is not simply hoping for a better outcome. They are actively participating in the recalibration of their endocrine system. The goal is to shift the body’s foundational state from one of high alert to one of safety and equilibrium, thereby creating the necessary biological conditions for the HPG axis to function without suppression and for spermatogenesis to proceed optimally.

Academic

An academic exploration of stress-mediated male infertility requires moving beyond systemic hormonal descriptions to the cellular and molecular level. The central question evolves from if stress affects fertility to how it exacts its toll on gamete viability. The concept of allostatic load provides a critical framework.

Allostasis is the process of maintaining stability through change; allostatic load is the cumulative physiological wear and tear that results from chronic adaptation to stressors. In the context of male fertility, this “load” manifests as quantifiable molecular damage to sperm, particularly to their genetic payload.

Sperm DNA Fragmentation a Primary Consequence

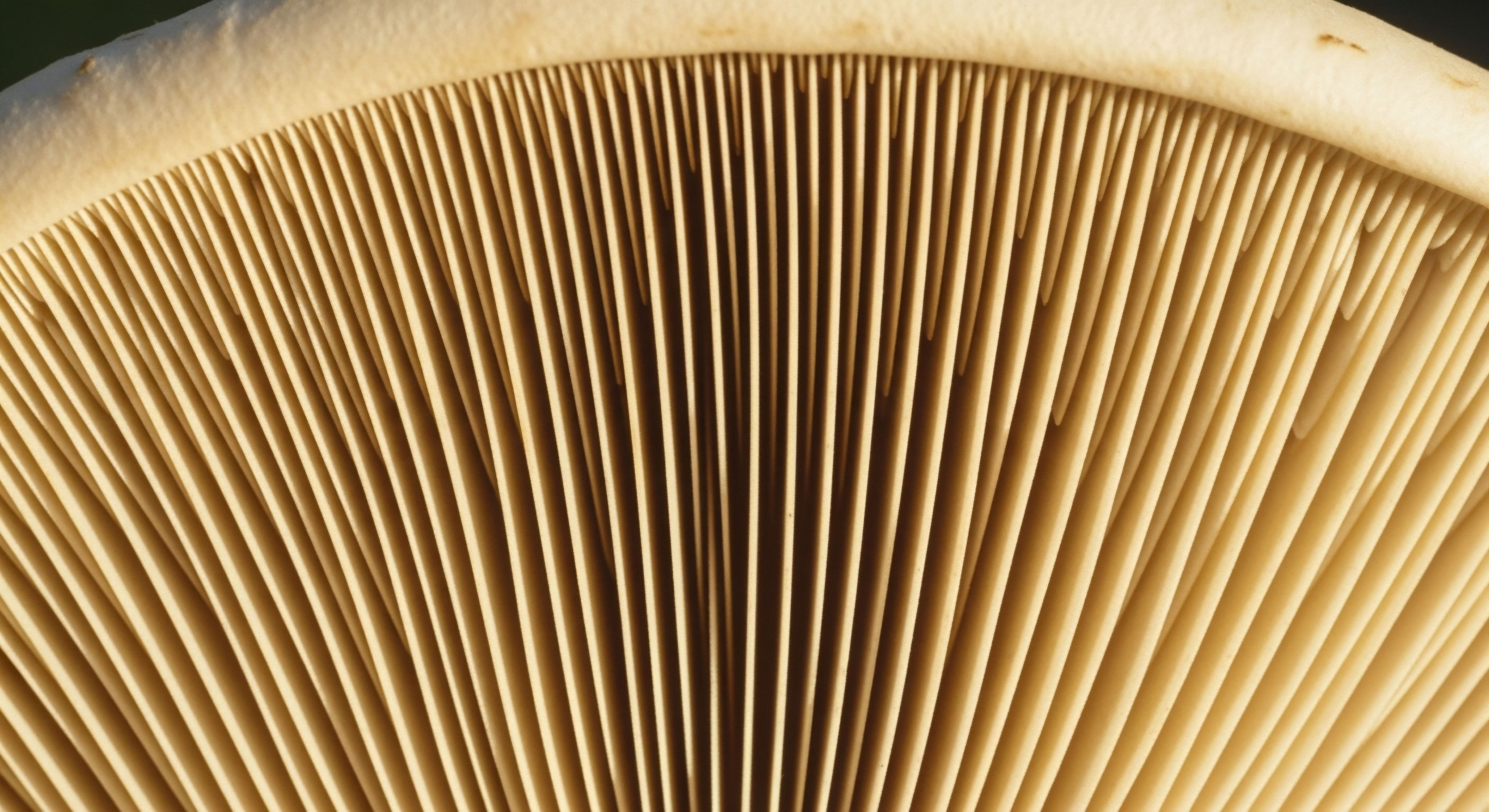

While traditional semen analysis measures parameters like count, motility, and morphology, these metrics do not fully describe the reproductive potential of sperm. A more advanced and clinically significant biomarker is sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF). High SDF indicates damage to the DNA strands within the sperm head.

While the oocyte has some capacity to repair DNA damage upon fertilization, extensive fragmentation can overwhelm this mechanism, leading to failed fertilization, poor embryo development, and early pregnancy loss. Chronic psychological stress is a significant etiological factor in elevated SDF. The primary mechanism is the overproduction of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) within the testicular microenvironment.

Spermatids, the precursors to mature spermatozoa, are particularly susceptible to oxidative damage during their development. The process of spermiogenesis involves the compaction of chromatin and the shedding of most of the cytoplasm, which contains the cell’s natural antioxidant defenses. Mature sperm, therefore, have very limited intrinsic capacity to repair oxidative damage.

Chronic stress, by increasing systemic cortisol and catecholamine levels, fuels inflammation and metabolic changes that result in a surge of ROS, overwhelming the antioxidant capacity of the seminal plasma and leading to lipid peroxidation of the sperm membrane and fragmentation of its DNA.

The invisible burden of chronic stress becomes visible under the microscope as damage to the very DNA that sperm are meant to deliver.

Can Behavioral Interventions Mitigate Molecular Damage?

The proposition that stress management can improve fertility outcomes is, at its core, a hypothesis that behavioral modification can reverse or mitigate cellular damage. Research supports this. Studies investigating the impact of psychological interventions on semen quality have shown promising results.

For example, a linear negative association has been detected between perceived stress scores and key semen parameters, including sperm concentration and motility. Some studies show that men participating in stress reduction programs, such as those based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), exhibit not only lower levels of anxiety and depression but also improvements in semen parameters.

- Neuro-Endocrine Modulation ∞ Interventions like MBSR are shown to reduce activity in the amygdala (the brain’s threat detection center) and increase prefrontal cortex engagement, leading to better top-down regulation of the HPA axis. This translates to lower circulating glucocorticoids (cortisol), reducing the direct suppressive pressure on the HPG axis.

- Antioxidant System Enhancement ∞ By lowering the physiological stress state, these techniques reduce the systemic production of ROS. Furthermore, the lifestyle changes often accompanying stress management, such as improved diet and regular moderate exercise, can increase the body’s endogenous antioxidant capacity, providing better protection for developing sperm.

- Autonomic Nervous System Rebalancing ∞ Chronic stress leads to sympathetic nervous system dominance. Techniques that promote parasympathetic tone, such as controlled breathing, can improve blood flow. Assertive or confrontational coping styles have been associated with increased adrenergic activation, leading to vasoconstriction in the testes, which can lower testosterone and impair spermatogenesis. Calming the system may improve testicular perfusion.

Limitations and the Role of Integrated Care

It is clinically crucial to recognize the limitations of stress management as a standalone therapy. While it is a powerful and necessary component of care for many men experiencing infertility, it cannot reverse structural pathologies like a high-grade varicocele, clear a physical obstruction, or correct a primary genetic abnormality.

A diagnosis of male factor infertility necessitates a thorough urological and endocrinological evaluation. Stress may be a significant contributing factor or an exacerbating element, but it may not be the sole cause. Therefore, the most effective clinical approach is an integrated one.

Stress management techniques should be implemented as an adjunct to, not a replacement for, appropriate medical or surgical treatment. For instance, a man undergoing a fertility-stimulating protocol with Gonadorelin or Clomid will likely achieve better results if his HPA axis is not simultaneously working to suppress his reproductive system. The psychological distress that accompanies an infertility diagnosis is a significant clinical factor in itself, and addressing it is essential for patient well-being and treatment adherence.

In conclusion, from an academic perspective, stress management is a targeted intervention aimed at reducing the allostatic load on the male reproductive system. Its efficacy is rooted in its ability to modulate neuroendocrine pathways, reduce oxidative stress at a cellular level, and mitigate the molecular damage that impairs sperm function, particularly DNA fragmentation. While not a panacea, it is an evidence-based, non-negotiable pillar of comprehensive fertility care.

References

- Ilacqua, A. et al. “Lifestyle and fertility ∞ the influence of stress and quality of life on male fertility.” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, vol. 16, no. 1, 2018, p. 115.

- Nassan, F.L. et al. “Biomarkers of Stress and Male Fertility.” Journal of Urology, vol. 207, no. 2, 2022, pp. 419-427.

- McGrady, A.V. “Effects of psychological stress on male reproduction ∞ a review.” Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine, vol. 19, no. 1, 1989, pp. 1-7.

- Purewal, S. et al. “Psychological consequences of a diagnosis of infertility in men ∞ a systematic analysis.” Asian Journal of Andrology, vol. 26, no. 1, 2024, pp. 34.

- “The Role of Stress Management in Enhancing Male Fertility.” Posterity Health, 29 May 2023.

- “Infertility Stresses Men Too, According to New Research.” ARC Fertility.

- “Understanding the Impact of Stress on Male Fertility.” Novomed.

- Cirino, E. “10 Ways to Boost Male Fertility and Increase Sperm Count.” Healthline, 7 June 2024.

- “Anxiety is Prevalent Among Infertile Men, New Study Shows.” Medical Electronic Systems, 31 July 2024.

- Lotti, F. and Maggi, M. “The impact of stress on male fertility.” Nature Reviews Urology, vol. 15, no. 6, 2018, pp. 367-378.

Reflection

Viewing Your Biology as an Ally

The information you have absorbed is more than a collection of biological facts. It is a new lens through which to view your own body and its responses. The symptoms you experience, including the immense stress of this process, are not signs of failure. They are communications. Your body is reporting on its current state, responding logically to the environment it perceives. The challenge, and the opportunity, lies in learning to change that perception from within.

This knowledge can transform your relationship with your own health. Instead of feeling like a passive subject of a difficult diagnosis, you can become an active participant in your own physiological recalibration. Each conscious breath, each walk, each prioritized hour of sleep is a direct input into the system, a message of safety sent to your own endocrine command center.

This journey is profoundly personal. The data and mechanisms provide the map, but you are the one navigating the terrain. Consider what your body has been trying to tell you, and how you can begin to change the conversation.