Fundamentals

You feel it. A persistent hum of exhaustion that sleep does not seem to touch. A subtle but unyielding sense of being overwhelmed, where the capacity to handle life’s demands feels diminished. These feelings are valid, and they are rooted in your biology.

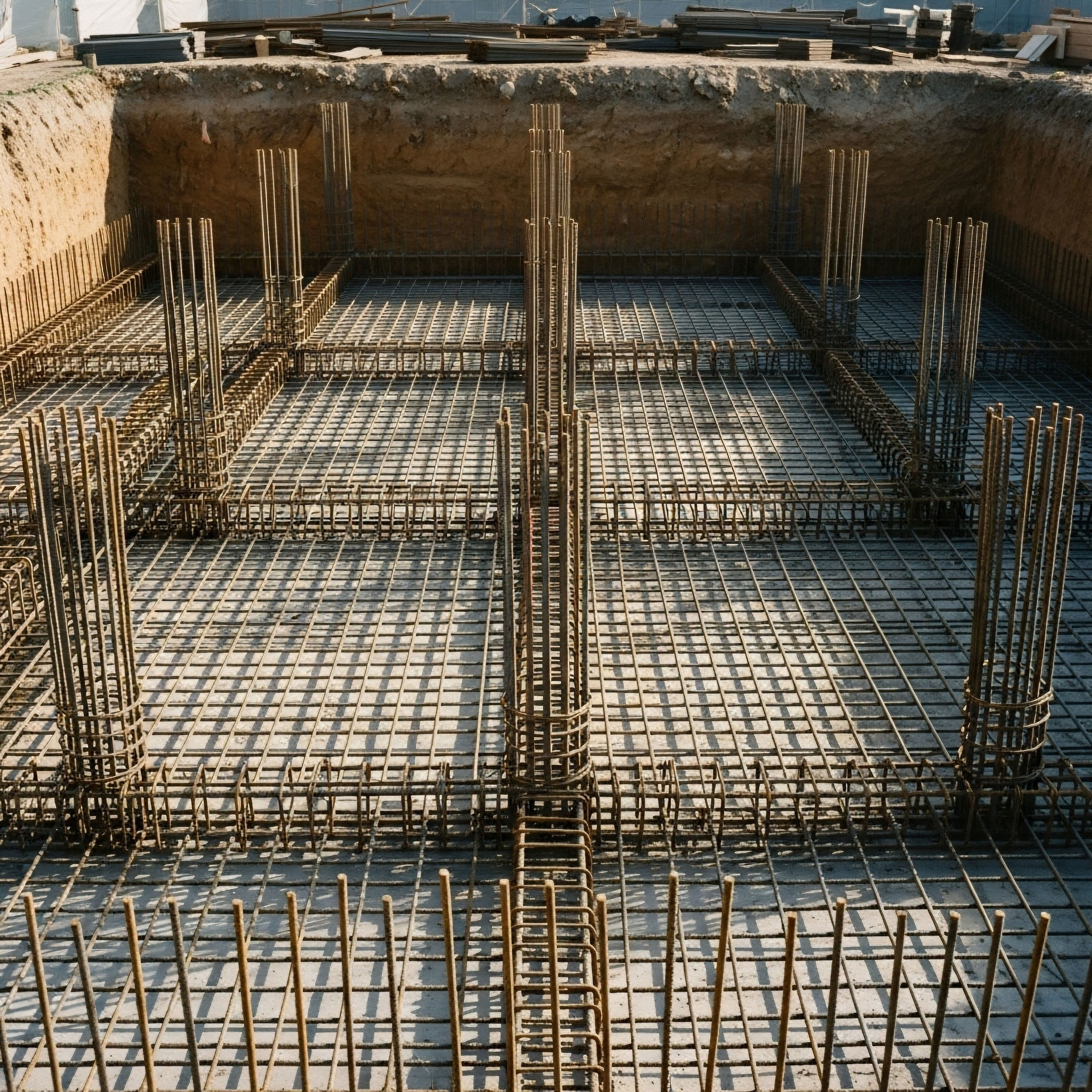

Your body is equipped with an incredibly sophisticated system for managing challenges, a system designed for acute, short-term events. The disconnect you experience arises when this system is left running indefinitely. We can begin to understand this by looking directly at the body’s primary stress-response mechanism ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. This is your central command and control for hormonal regulation in the face of a perceived threat.

The process begins in the brain. When you encounter a stressor, your hypothalamus, a small but powerful region at the base of your brain, releases a chemical messenger called Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH). This is the initial signal, the system’s alert.

CRH travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the master gland of the endocrine system, instructing it to release Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream. ACTH then journeys to the adrenal glands, which are small, triangular glands sitting atop your kidneys.

Upon receiving the ACTH signal, your adrenals produce and release cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. This entire cascade is elegant, efficient, and life-sustaining. Cortisol mobilizes energy, increases alertness, and modulates the immune system, preparing you to handle the challenge at hand.

Once the threat passes, a negative feedback loop is designed to shut the system down. Rising cortisol levels signal the hypothalamus and pituitary to stop secreting CRH and ACTH, and the system returns to a state of balance, or homeostasis.

The body’s stress response is a precise, cascading hormonal system designed for acute threats, not chronic activation.

The challenge of modern life is the chronic nature of our stressors. Financial pressures, demanding careers, relationship difficulties, and constant digital stimulation are not the short-lived physical threats our biology evolved to manage. They are persistent, low-grade pressures that keep the HPA axis perpetually activated.

This constant signaling prevents the negative feedback loop from properly engaging. The result is a state of prolonged endocrine disruption. Your body is continuously bathed in cortisol, and the systems it influences begin to show signs of strain. This is the biological reality behind the feelings of exhaustion, brain fog, and emotional dysregulation. It is a physiological state, a direct consequence of a system operating outside of its intended parameters.

The Central Role of Cortisol

Cortisol is essential for life, performing numerous critical functions. It helps regulate blood sugar levels, reduce inflammation, and manage metabolism. In the right amounts, it is a cornerstone of health. When chronically elevated due to an overactive HPA axis, its effects become detrimental.

The same hormone that provides a burst of energy by tapping into glucose stores can, over time, contribute to insulin resistance and fat storage, particularly around the abdomen. The same anti-inflammatory properties that are beneficial in the short term can, with prolonged exposure, suppress the immune system, leaving you more susceptible to illness.

This is why chronic stress is so frequently linked to a wide array of health issues. The very mechanism designed to protect you in the short term begins to create systemic problems when it remains active for too long.

From Overdrive to Burnout

The initial phase of HPA axis dysregulation is often characterized by high cortisol levels. People in this stage might feel “wired but tired,” anxious, and unable to relax. They may struggle with sleep, waking frequently during the night as their cortisol rhythm becomes disrupted.

Over an extended period of this over-activation, the system can begin to adapt in a different way. The brain may reduce its sensitivity to cortisol’s feedback signals, or the adrenal glands themselves may become less responsive to ACTH. This can lead to a state of hypocortisolism, where the body is unable to produce enough cortisol to meet its needs.

This is the state often colloquially referred to as “adrenal fatigue.” Clinically, it represents a profound dysregulation of the HPA axis. Symptoms in this stage often include deep fatigue, low blood pressure, dizziness upon standing, and a reduced ability to handle any form of stress. The journey from high to low cortisol is a continuum of dysfunction, driven by the unrelenting demand placed on the system.

Can Simple Relaxation Fix a Systemic Problem?

This exploration of the HPA axis provides a direct answer to the central question. Stress management techniques like meditation, deep breathing, and mindfulness are absolutely essential. They are the first and most important step because they directly address the input signal. By calming the nervous system, you reduce the hypothalamus’s drive to release CRH, thereby quieting the entire HPA cascade. This is a powerful and necessary intervention. It turns down the alarm that has been ringing incessantly.

However, once the system has been operating in a state of chronic overdrive, physiological changes have already occurred. The glands themselves may have altered in their functional capacity, and the brain’s receptors may have become less sensitive. Simply turning off the alarm does not instantly repair the wiring or restore the hardware to its original condition.

Restoring true endocrine equilibrium often requires a two-pronged approach. First, the stress signals must be managed and reduced. Second, the biological systems that have been compromised need direct support to regain their proper function and balance. This is where a deeper, more personalized approach to wellness becomes necessary, one that acknowledges the physical reality of HPA axis dysregulation and provides the resources for its recovery.

Intermediate

Understanding that chronic stress induces physical changes in the endocrine system allows us to move toward a more sophisticated and effective model of recovery. The concept of HPA axis dysregulation is not a single state, but a spectrum of adaptation that can ultimately lead to systemic breakdown.

To intervene effectively, we must appreciate the nuances of this process and the specific ways in which it impacts other interconnected hormonal systems. The body does not operate in silos; a disruption in one axis inevitably ripples through others, affecting metabolism, reproductive health, and overall vitality.

The progression from a healthy stress response to profound dysregulation often follows a predictable, albeit damaging, path. Initially, in response to a persistent stressor, the HPA axis mounts a robust response, leading to hypercortisolism. This is a state of high alert. As this state is maintained, the body begins a process of adaptation.

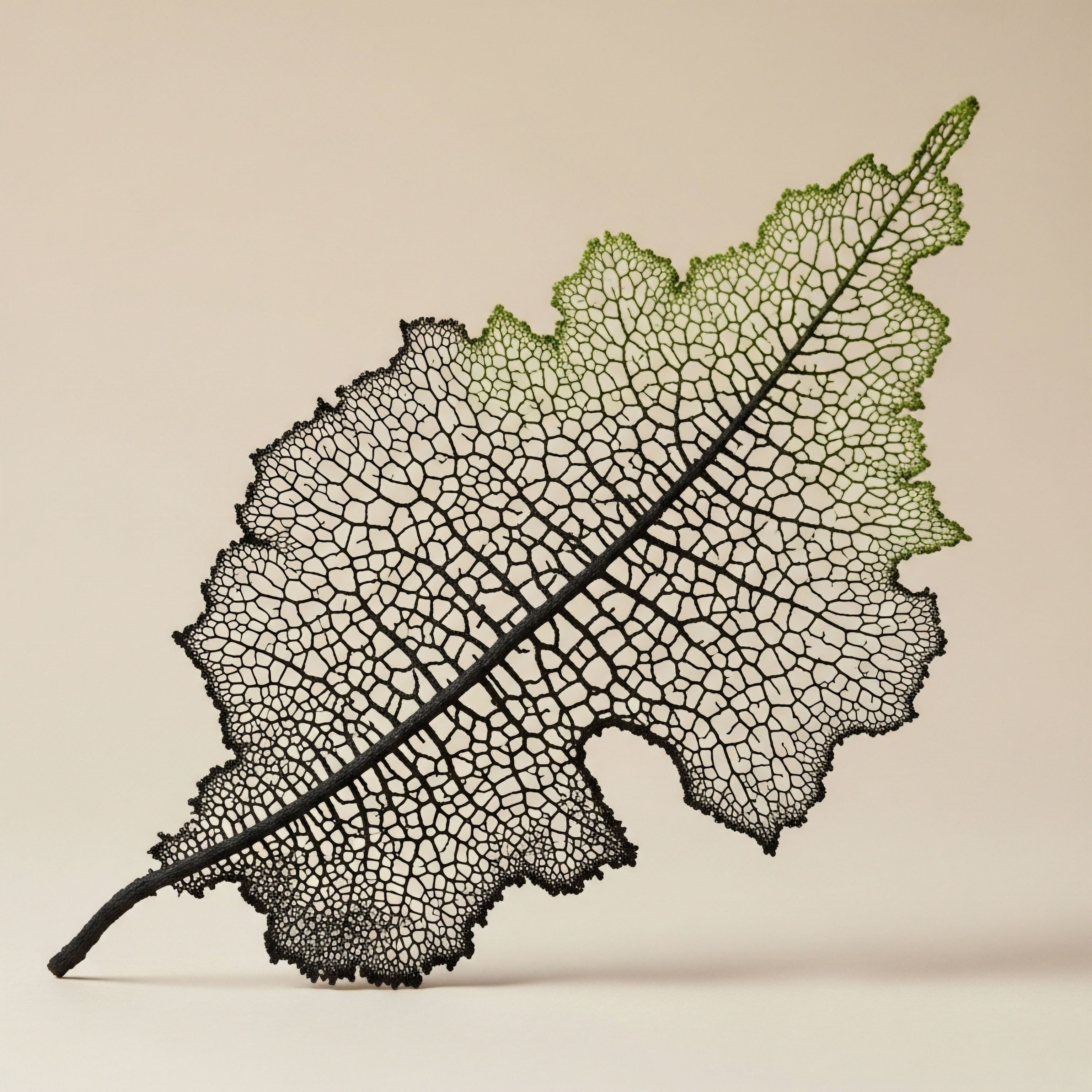

One critical concept in this phase is the “pregnenolone steal” phenomenon. Pregnenolone is a precursor hormone, a foundational building block from which the body synthesizes both cortisol and other vital steroid hormones, including DHEA and testosterone. Under conditions of chronic stress, the biochemical pathways prioritize the production of cortisol to meet the relentless demand.

This effectively “steals” pregnenolone away from the pathways that produce other hormones. The consequence is a decline in DHEA, often called the “youth hormone” for its role in vitality and resilience, and a potential suppression of gonadal hormones like testosterone and estrogen.

The Interconnected Web of Hormonal Decline

The dysregulation of the HPA axis is a primary driver of broader endocrine imbalance. The consequences of chronically elevated cortisol and depleted DHEA extend far beyond the stress response itself. This systemic disruption is often the root cause of symptoms that may seem unrelated at first glance.

Impact on the Thyroid Axis

The thyroid gland, which governs metabolism, is exquisitely sensitive to cortisol levels. High cortisol can inhibit the conversion of the inactive thyroid hormone T4 into the active form T3. This can lead to symptoms of hypothyroidism, such as fatigue, weight gain, and cold intolerance, even when standard thyroid lab tests appear to be within the normal range. The body, in its attempt to conserve energy during a perceived crisis, effectively puts the brakes on its metabolic rate.

Suppression of Gonadal Function

The reproductive hormones are also significantly affected. In both men and women, chronic stress and high cortisol can suppress the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This is the command chain that governs the production of testosterone in men and the regulation of the menstrual cycle in women.

In men, this can manifest as low libido, erectile dysfunction, and a loss of muscle mass, symptoms characteristic of low testosterone. In women, it can lead to irregular cycles, worsening PMS, and fertility challenges. The body essentially decides that a state of chronic emergency is not an appropriate time for reproduction, and it down-regulates the associated hormonal systems accordingly.

Chronic stress systematically de-prioritizes metabolic and reproductive functions by shunting hormonal resources toward cortisol production.

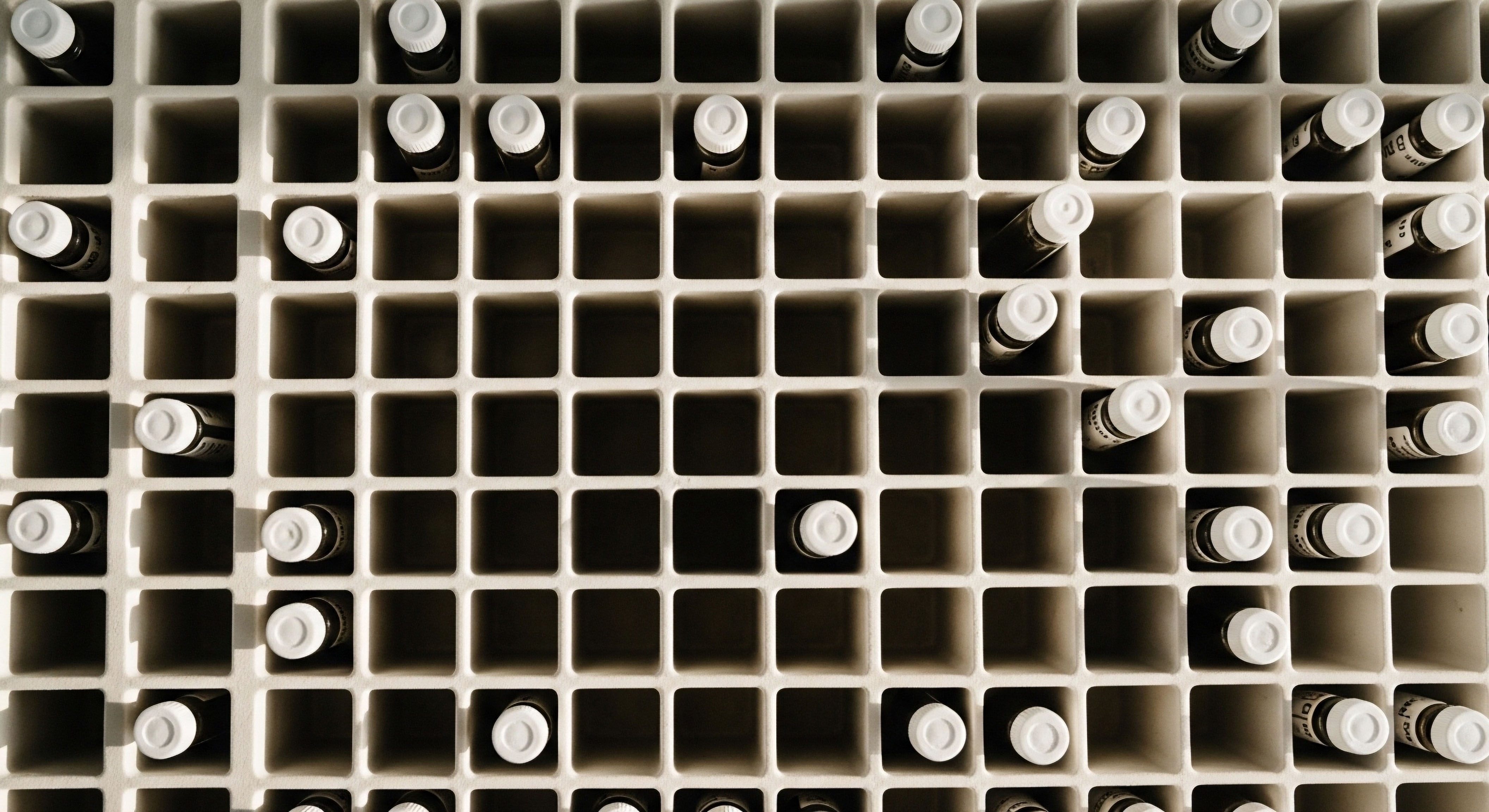

The table below illustrates the contrasting symptoms of the two primary stages of HPA axis dysregulation, showing the progression from an over-activated state to one of exhaustion.

| Symptom Category | Hypercortisolism (Early Stage) | Hypocortisolism (Late Stage) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy |

Feeling “wired but tired”; difficulty relaxing; a false sense of energy. |

Profound fatigue; exhaustion not relieved by sleep; post-exertional malaise. |

| Sleep |

Difficulty falling asleep; frequent waking, especially between 2-4 AM. |

Needing excessive sleep to function; feeling unrefreshed upon waking. |

| Mood |

Anxiety; irritability; feeling overwhelmed or agitated. |

Apathy; depression; emotional flatness; low resilience. |

| Metabolism |

Cravings for sugar and salt; increased abdominal fat storage; insulin resistance. |

Low blood sugar episodes; salt loss; inability to lose weight. |

| Immunity |

Frequent colds and infections due to immune suppression. |

Potential for inflammatory or autoimmune conditions to flare up. |

Why Stress Management Requires Clinical Support

Given these profound physiological changes, it becomes clear why stress management alone, while critical, may be insufficient for a full recovery. It is akin to taking your foot off the accelerator of a car that has already sustained engine damage. You have stopped causing further harm, but the existing damage needs to be repaired.

This is where targeted clinical protocols become a necessary component of restoring endocrine equilibrium. These protocols are not a replacement for stress management; they are a complementary strategy designed to support the body’s healing process and restore function to the compromised systems.

Restoring the Foundations with Hormonal Support

When lab testing confirms that chronic stress has suppressed gonadal function, carefully managed hormone optimization can provide the body with the resources it needs to recover.

- Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for Men ∞ For men whose testosterone levels have been suppressed by chronic HPA axis activation, TRT can help restore vitality, muscle mass, and cognitive function.

A typical protocol might involve weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate. This is often paired with agents like Gonadorelin to help maintain the body’s own natural signaling pathways and preserve fertility.

- Hormone Support for Women ∞ For women, particularly those in the perimenopausal or menopausal transition where hormonal reserves are already declining, chronic stress can dramatically worsen symptoms.

Protocols may include low-dose Testosterone Cypionate to improve energy, mood, and libido, along with progesterone to support sleep and emotional stability. These interventions provide a foundation of stability from which the body can begin to heal.

Utilizing Peptides to Restore Signaling

Peptide therapies represent a more targeted approach to restoring endocrine function. Peptides are small protein chains that act as precise signaling molecules. In the context of HPA axis recovery, they can be used to gently stimulate the body’s own production of hormones that have been blunted by chronic stress.

- Growth Hormone Peptides ∞ Chronic stress can suppress the release of Growth Hormone (GH), which is vital for tissue repair, metabolism, and sleep quality. Peptides like Sermorelin or the combination of Ipamorelin and CJC-1295 work by stimulating the pituitary gland to release its own GH in a natural, pulsatile manner. This can help improve sleep architecture, enhance recovery, and counteract some of the catabolic effects of excess cortisol.

These clinical strategies are designed to work in concert with foundational stress management. By reducing the stress input and simultaneously providing targeted support to the compromised endocrine systems, it becomes possible to guide the body back toward a state of true, resilient equilibrium. The goal is a comprehensive restoration of the body’s innate capacity for health and function.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of endocrine restoration necessitates moving beyond the phenomenological description of HPA axis dysregulation to a detailed examination of the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms. The proposition that stress management alone can restore equilibrium is challenged by the evidence of persistent structural and functional alterations within the neuroendocrine system.

Chronic stress initiates a cascade of events that includes glucocorticoid receptor desensitization, neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and even morphological changes in the endocrine glands themselves. These adaptations are not merely transient states; they represent a new, pathological homeostasis that can become self-perpetuating, requiring targeted biochemical intervention to disrupt.

Glucocorticoid Receptor Dynamics and Cellular Resistance

The biological effects of cortisol are mediated by the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a protein found in virtually all cells of the body. In a healthy system, cortisol binds to the GR, and the resulting complex translocates to the nucleus to regulate gene expression.

This is the mechanism behind cortisol’s effects on metabolism and inflammation, as well as the negative feedback signal to the hypothalamus and pituitary. Under conditions of chronic hypercortisolism, cells protect themselves from overstimulation by down-regulating the number of GRs on their surface or by altering the receptor’s binding affinity. This is the phenomenon of glucocorticoid resistance.

This acquired resistance has profound consequences. In the brain, particularly in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, GR resistance impairs the negative feedback loop. The brain no longer effectively senses the high levels of cortisol, so the hypothalamus continues to secrete CRH, perpetuating the HPA axis activation.

This creates a vicious cycle of rising cortisol levels and deepening central GR resistance. Peripherally, GR resistance means that higher levels of cortisol are needed to achieve the same anti-inflammatory effect, which can lead to a state of systemic inflammation coexisting with high cortisol, a condition implicated in a host of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Restoring equilibrium requires interventions that can resensitize these receptor sites, a process that may not occur spontaneously simply by removing the stressor.

What Are the Implications of Altered Glandular Mass?

Recent mathematical modeling and experimental data suggest a fascinating and critical component of long-term HPA axis dysregulation ∞ changes in the functional mass of the endocrine glands themselves. The hormones of the HPA axis, such as ACTH, act as trophic factors for their target glands.

Chronic stimulation of the adrenal cortex by ACTH can lead to adrenal hypertrophy, an increase in the size and secretory capacity of the gland. Conversely, prolonged suppression of the pituitary by high cortisol levels could, over time, lead to a reduction in the corticotroph cell population responsible for producing ACTH.

These changes in gland mass represent a long-term structural adaptation to the chronic stress signal. Once these changes have occurred, the system has a new, altered baseline. Removing the stressor does not instantly remodel the glands back to their original state. This provides a compelling mechanical explanation for why HPA axis dysregulation can persist long after the period of stress has ended and why targeted therapies may be needed to restore the system’s original architecture and function.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction as a Core Pathological Mechanism

The link between chronic stress and cellular energy production is a critical area of research. Mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell, are deeply involved in the stress response. They are not only the primary site of ATP production but are also integral to the synthesis of steroid hormones within the adrenal glands.

Research has shown that chronic unpredictable stress induces significant, sex-specific mitochondrial dysfunction in key regions of the HPA axis. For instance, studies in animal models have demonstrated decreased mitochondrial respiration in the hypothalamus and adrenal glands following prolonged stress.

This means the very tissues responsible for managing the stress response become less efficient at producing the energy required for their own function and for hormone synthesis. This creates a cellular energy crisis at the heart of the endocrine system. The resulting oxidative stress and impaired energy metabolism can further damage cells, contributing to neuroinflammation and accelerating the decline in endocrine function. Interventions that support mitochondrial health, therefore, become a logical and necessary component of any comprehensive recovery protocol.

Chronic stress inflicts lasting structural and functional damage at the cellular level, including receptor desensitization and mitochondrial impairment.

The table below outlines specific advanced therapeutic protocols designed to address these deep-seated biological disruptions, moving beyond simple hormone replacement to a more nuanced recalibration of the endocrine system.

| Therapeutic Agent | Mechanism of Action | Clinical Application in Stress-Induced Dysfunction |

|---|---|---|

| Tesamorelin |

A Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) analogue that stimulates the pituitary’s endogenous production of growth hormone. |

Counteracts the stress-induced suppression of the GH axis, improving sleep quality, metabolic function, and promoting anabolic repair processes to combat cortisol’s catabolic effects. |

| Enclomiphene |

A selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that blocks estrogen’s negative feedback at the pituitary, increasing LH and FSH production. |

Used in men to restart the HPG axis suppressed by chronic stress, stimulating the testes to produce testosterone endogenously, thereby restoring the system’s natural function. |

| Anastrozole |

An aromatase inhibitor that blocks the conversion of testosterone to estrogen. |

Used judiciously in TRT protocols to manage estrogen levels, which can become elevated due to increased substrate from testosterone therapy, preventing side effects and maintaining hormonal balance. |

| PT-141 (Bremelanotide) |

A melanocortin receptor agonist that acts within the central nervous system to influence sexual arousal pathways. |

Addresses stress-induced low libido at a neurological level, bypassing the often-suppressed hormonal pathways to directly support sexual health and function. |

The Rationale for a Post-TRT or Fertility Protocol

In some cases, particularly in men who have been on TRT to counteract stress-induced hypogonadism, there is a desire to discontinue therapy and restore the body’s innate hormonal production, often for fertility purposes. This process requires a sophisticated understanding of the HPG axis feedback loops.

A protocol involving agents like Gonadorelin, Clomid (clomiphene), and Tamoxifen is designed to systematically restart the suppressed system.

- Gonadorelin ∞ A GnRH analogue that directly stimulates the pituitary to produce LH and FSH, signaling the testes to produce testosterone and support spermatogenesis.

- Clomid/Tamoxifen ∞ These SERMs block estrogen feedback at the hypothalamus and pituitary, effectively tricking the brain into thinking estrogen is low and thereby increasing its output of LH and FSH.

This type of protocol acknowledges a fundamental truth ∞ restoring a complex biological system often requires a period of guided, active management. The endocrine equilibrium disrupted by chronic stress is a dynamic system. Returning to balance is an active process of recalibration. While stress management creates the necessary environment for healing, targeted biochemical and hormonal interventions provide the precise tools needed to repair and reset the underlying machinery, guiding the system back to a state of resilient and self-sustaining health.

References

- Point Institute. “Chronic Stress and the HPA Axis.” Point Institute, 2010.

- Stanciu, M. et al. “Chronic Stress-Associated Depressive Disorders ∞ The Impact of HPA Axis Dysregulation and Neuroinflammation on the Hippocampus ∞ A Mini Review.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 12, 2023, p. 10243.

- Geva, N. and U. Alon. “A new model for the HPA axis explains dysregulation of stress hormones on the timescale of weeks.” Molecular Systems Biology, vol. 16, no. 10, 2020, p. e9510.

- Nicolaides, N. C. et al. “Stress ∞ Endocrine Physiology and Pathophysiology.” Endotext, edited by K. R. Feingold et al. MDText.com, Inc. 2020.

- Wilson, C. et al. “Chronic Unpredictable Stress Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal Axis Regions.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2024.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map of the biological territory you inhabit. It connects the feelings you experience to the intricate functions of your internal systems. This knowledge is a powerful first step. It transforms a vague sense of being unwell into a clear understanding of a physiological process.

The question now becomes personal. Where on this map do you see yourself? Recognizing the patterns of hypervigilance or deep exhaustion in your own life is the beginning of a new conversation with your body. This understanding empowers you to ask more precise questions and to seek solutions that honor the complexity of your unique biology.

The path toward reclaiming your vitality is one of partnership, combining your own commitment to managing life’s pressures with the clinical guidance needed to support and rebuild the very foundation of your health.