Understanding Your Body’s Resilience

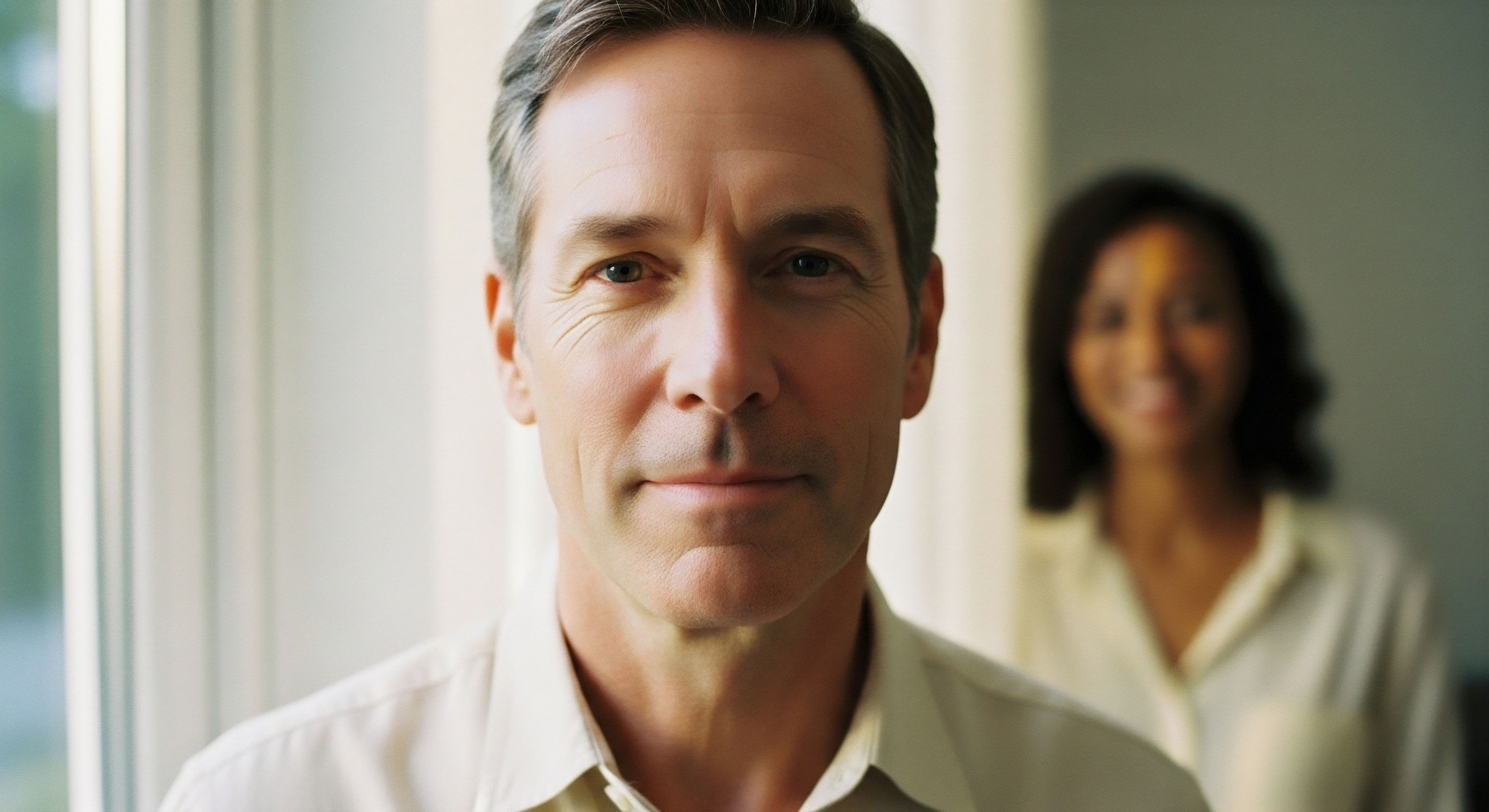

Many individuals recognize a shift in their physical and mental state as life’s demands intensify. Perhaps a persistent weariness settles in, or body composition subtly changes despite consistent efforts. These experiences are not merely subjective observations; they often signal a deeper recalibration within the body’s sophisticated internal messaging network.

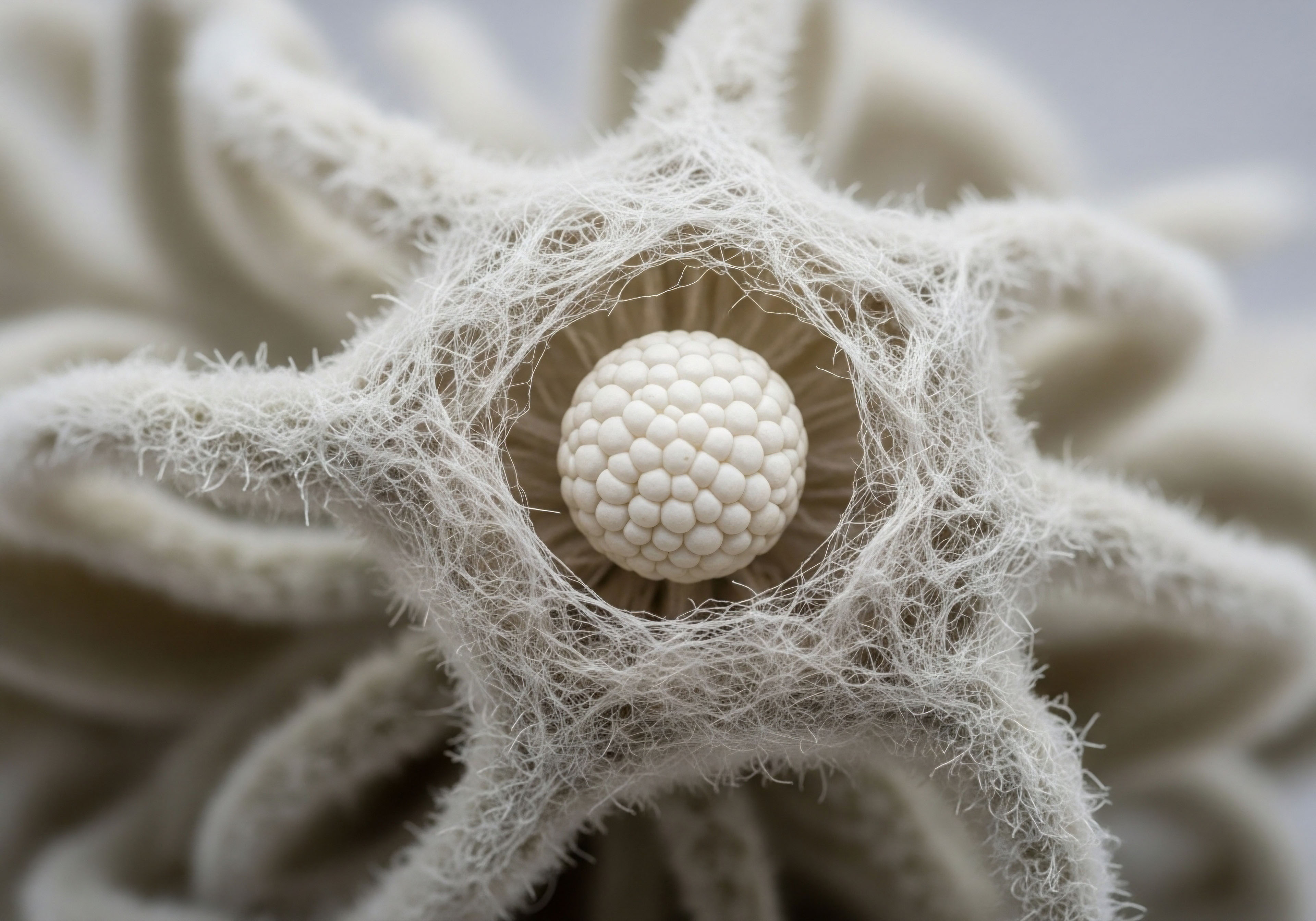

The body’s endocrine system, a symphony of glands and hormones, orchestrates vitality and function. Growth hormone, a central player in this orchestration, significantly contributes to tissue repair, metabolic regulation, and overall energetic disposition. Its presence helps maintain lean muscle mass, supports bone density, and influences the body’s capacity for cellular regeneration.

Chronic physiological stressors exert a profound influence on this delicate hormonal balance. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s primary stress response system, becomes activated. This activation leads to an increased secretion of cortisol, often termed the body’s principal stress hormone. While acute, transient elevations of cortisol serve adaptive purposes, sustained high levels can initiate a cascade of downstream effects, impacting various other endocrine pathways.

Growth hormone plays a central role in adult vitality, influencing tissue repair, metabolism, and overall energy.

The Hormonal Orchestra and Its Conductors

The human body functions as a complex, interconnected system, where no single hormone operates in isolation. Growth hormone (GH) secretion, for instance, originates from the anterior pituitary gland, yet its release is under constant regulatory influence from the hypothalamus in the brain.

The hypothalamus releases two key neurohormones ∞ growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), which stimulates GH secretion, and somatostatin, which inhibits it. A dynamic interplay between these two hypothalamic signals establishes the characteristic pulsatile release of GH throughout the day and night. Sleep, physical activity, and nutritional status are among the many factors that influence this pulsatile pattern.

Understanding this intricate regulatory network offers a clearer perspective on how external pressures, such as prolonged psychological stress, can ripple through the system. The body’s response to stress is a testament to its adaptive capacity, yet chronic activation can lead to systemic shifts that affect more than just immediate survival mechanisms. These systemic shifts extend to the very hormones that dictate our long-term health and functional capacity.

Interplay of Stress Hormones and Anabolism

For those familiar with the fundamental principles of hormonal regulation, the subsequent step involves comprehending the specific mechanisms through which persistent stress disrupts growth hormone dynamics. The primary mechanism involves the HPA axis’s central role in modulating the somatotropic axis. Elevated and sustained cortisol levels, a hallmark of chronic stress, directly impact the hypothalamic regulation of growth hormone. Cortisol influences the production and release of both GHRH and somatostatin, tipping the delicate balance.

Research indicates that sustained glucocorticoid exposure suppresses the hypothalamic secretion of GHRH, simultaneously enhancing the release of somatostatin. This dual action directly diminishes the pulsatile release of GH from the anterior pituitary gland. Consequently, the overall anabolic drive, which GH and its downstream mediator, Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1), facilitate, becomes attenuated. This attenuation can manifest as reduced capacity for muscle protein synthesis, impaired tissue regeneration, and altered fat metabolism, often observed as an increase in central adiposity.

Chronic stress, through sustained cortisol, suppresses GHRH and enhances somatostatin, reducing growth hormone release.

Strategic Interventions for Endogenous Support

While the impact of chronic stress on growth hormone levels is significant, a range of strategic, non-pharmacological interventions can support endogenous GH secretion. These approaches primarily aim to mitigate the HPA axis overactivity and restore physiological balance.

- Sleep Optimization ∞ Deep, restorative sleep is a potent physiological stimulus for growth hormone release. Establishing consistent sleep schedules, ensuring a cool, dark sleep environment, and avoiding blue light exposure before bedtime significantly enhance the body’s natural nocturnal GH pulses.

- Mind-Body Practices ∞ Techniques such as mindfulness meditation, diaphragmatic breathing, and progressive muscle relaxation directly reduce sympathetic nervous system activation and lower circulating cortisol levels. This reduction in stress hormones indirectly supports a more favorable environment for GHRH release.

- Regular Physical Activity ∞ Moderate to high-intensity exercise acutely stimulates growth hormone secretion. Consistent engagement in resistance training and interval-based cardiovascular exercise can contribute to sustained improvements in GH pulsatility and overall metabolic health.

- Nutritional Support ∞ A balanced diet rich in micronutrients and adequate protein supports overall endocrine function. Avoiding excessive sugar intake and adopting meal timing strategies, such as intermittent fasting, can influence insulin sensitivity and, by extension, GH secretion.

These lifestyle modifications, when consistently applied, address the root causes of stress-induced hormonal dysregulation. They work synergistically to recalibrate the neuroendocrine system, thereby fostering an environment conducive to optimized growth hormone production.

Can Lifestyle Changes Reclaim Hormonal Balance?

The question arises whether these lifestyle interventions alone can fully restore growth hormone levels to optimal ranges, particularly in the context of significant age-related decline or prolonged stress. The efficacy of stress management protocols depends on the individual’s baseline health, the chronicity and intensity of the stressors, and the degree of existing hormonal dysregulation.

| Intervention Strategy | Primary Mechanism of Action | Potential Effect on GH Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized Sleep | Enhances nocturnal GH pulsatility, reduces HPA axis activity. | Significant increase in natural GH secretion. |

| Mindfulness & Relaxation | Lowers cortisol, shifts autonomic balance towards parasympathetic. | Indirectly supports GHRH release and reduces GH inhibition. |

| Consistent Exercise | Acute GH release, improved metabolic health, reduced body fat. | Direct stimulation and long-term optimization of GH. |

| Strategic Nutrition | Improved insulin sensitivity, reduced inflammation. | Indirectly supports GH secretion and action. |

Glucocorticoid Receptor Dynamics and Somatotropic Axis Dysregulation

A deeper exploration into the relationship between chronic stress and growth hormone necessitates an examination of the molecular and cellular underpinnings of glucocorticoid action within the neuroendocrine system. Persistent elevation of cortisol, a primary glucocorticoid, exerts its effects through binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs), which are widely distributed throughout the brain and peripheral tissues, including the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. The activation of these receptors initiates a complex transcriptional program that directly modulates the somatotropic axis.

Within the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, chronic glucocorticoid excess significantly suppresses the gene expression and release of Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH). Simultaneously, it augments the synthesis and secretion of somatostatin from the periventricular nucleus. This coordinated action creates a powerful inhibitory environment for pituitary somatotrophs, thereby attenuating their responsiveness to any residual GHRH stimulation. The pulsatile nature of GH secretion, which is critical for its biological efficacy, becomes blunted, leading to a reduction in overall GH output.

Chronic cortisol suppresses GHRH gene expression and increases somatostatin, blunting pulsatile growth hormone release.

Molecular Mechanisms of Stress-Induced Growth Hormone Attenuation

The molecular mechanisms extending beyond simple suppression and stimulation involve intricate feedback loops and receptor desensitization. Chronic exposure to glucocorticoids can lead to a desensitization of GHRH receptors on pituitary somatotrophs, further impairing their ability to respond to GHRH. This desensitization can involve altered receptor phosphorylation, internalization, and a reduction in downstream signaling pathways, particularly the cAMP-dependent pathway that mediates GHRH’s stimulatory effects.

Moreover, sustained glucocorticoid presence influences hepatic Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) production, a key mediator of GH’s anabolic actions. Cortisol can directly inhibit IGF-1 synthesis in the liver, and it can also induce a state of tissue resistance to IGF-1, further compounding the anabolic deficit. This intricate molecular interference underscores why a holistic approach to stress management, targeting the fundamental physiological imbalances, holds substantial merit for optimizing endogenous growth hormone levels.

- Hypothalamic Suppression ∞ Chronic cortisol diminishes GHRH synthesis and release from the arcuate nucleus.

- Somatostatin Enhancement ∞ Elevated cortisol increases somatostatin production, intensifying its inhibitory effect on the pituitary.

- Pituitary Desensitization ∞ Sustained glucocorticoid exposure can reduce GHRH receptor sensitivity on somatotrophs.

- Hepatic IGF-1 Inhibition ∞ Cortisol directly impairs liver IGF-1 synthesis and induces peripheral tissue resistance to IGF-1.

Considering these molecular complexities, the effectiveness of stress management alone in fully restoring growth hormone levels becomes contingent upon the reversibility of these chronic adaptations. While significant improvements are attainable through lifestyle interventions, individuals with prolonged and severe HPA axis dysregulation might require more targeted endocrine system support to achieve optimal vitality and functional restoration.

| Neuroendocrine Factor | Effect of Chronic Stress | Consequence for GH Secretion |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) | Decreased synthesis and release. | Reduced stimulation of pituitary GH. |

| Somatostatin (SRIH) | Increased synthesis and release. | Enhanced inhibition of pituitary GH. |

| Cortisol | Sustained elevation. | Direct suppression of GHRH, enhancement of SRIH, GHRH receptor desensitization. |

| Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) | Decreased hepatic production, tissue resistance. | Reduced anabolic signaling, impaired feedback regulation. |

References

- Copeland, K. C. et al. “Growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) responses to growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) in children with short stature.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 63, no. 5, 1986, pp. 1102-1106.

- Jaffe, C. A. et al. “Impact of acute and chronic stress on growth hormone secretion.” Stress, vol. 1, no. 1, 1996, pp. 33-39.

- Papadimitriou, A. and G. Chrousos. “The neuroendocrinology of the stress response and its effects on growth.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1092, 2006, pp. 177-187.

- Van Cauter, E. and K. S. Polonsky. “Sleep and endocrine rhythms.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 18, no. 5, 1997, pp. 716-738.

- Veldhuis, J. D. and M. L. Johnson. “A method for analyzing pulsatile hormone secretion and its application to growth hormone.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 240, no. 5, 1981, pp. E377-E385.

- Giustina, A. and M. L. Veldhuis. “Pathophysiology of the neuroregulation of growth hormone secretion in disease states.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 19, no. 6, 1998, pp. 717-759.

- Hoppe, C. and M. L. Veldhuis. “The role of glucocorticoids in the regulation of growth hormone secretion.” Growth Hormone & IGF Research, vol. 11, no. 3, 2001, pp. 147-156.

- Fink, G. et al. “The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the control of growth hormone secretion.” Peptides, vol. 10, no. 5, 1989, pp. 881-886.

A Path to Reclaimed Vitality

The journey toward understanding one’s own biological systems marks a powerful step in reclaiming vitality and functional capacity. This exploration of stress and growth hormone illuminates the profound interconnectedness of the body’s endocrine landscape. The insights gained from examining these intricate biological mechanisms serve as a foundation, allowing for informed choices about personal wellness protocols. Recognizing the body’s inherent intelligence and its capacity for recalibration empowers individuals to pursue a personalized path toward optimal health.

This knowledge is merely the beginning. True transformation often stems from applying these scientific principles within the context of one’s unique physiological blueprint and lived experience. A truly personalized approach to wellness, guided by clinical understanding, offers the most direct route to restoring balance and achieving an uncompromising state of well-being.