Fundamentals

You may be standing at a point of profound contradiction. Your lifestyle is a testament to discipline ∞ every meal is considered, every workout is logged, and sleep is prioritized with near-religious dedication. Yet, you are confronting the deeply personal and frustrating reality of infertility.

The question that arises from this dissonance is a valid and pressing one ∞ can the intangible weight of stress, on its own, be sufficient to disrupt a system as fundamental as male reproduction? The answer is rooted in the body’s intricate and interconnected communication networks.

Your biology operates as a unified system, where the command center for stress and the command center for reproduction are in constant dialogue. When one is perpetually activated, the other can be systematically silenced. This is a journey into understanding that internal dialogue, recognizing how the biochemical signature of stress can override the signals required for fertility, even when every other aspect of your life is a picture of health.

The human body is governed by a series of sophisticated feedback loops, elegant systems of communication designed to maintain a state of internal balance, or homeostasis. Two of the most consequential of these systems are the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

Think of them as two distinct, yet deeply interconnected, governmental branches operating from the same capital city ∞ the brain. The HPA axis is the emergency response system. When you perceive a threat, whether it is a physical danger or a persistent psychological pressure like work deadlines or financial worries, the hypothalamus releases Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH).

This is the initial alarm. CRH signals the pituitary gland to release Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH), which then travels through the bloodstream to the adrenal glands, perched atop the kidneys. The adrenal glands, in turn, release cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. This entire cascade is designed for short-term survival, preparing the body to fight or flee by mobilizing energy reserves and heightening awareness.

A persistent state of alarm within the body’s stress response system can directly interfere with the hormonal signaling required for male reproductive health.

Parallel to this emergency system runs the HPG axis, the system responsible for regulating sexual development and reproduction. This process also begins in the hypothalamus, which releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in a pulsatile manner. These rhythmic pulses are of immense consequence; their frequency and amplitude are a carefully coded message to the pituitary gland.

Upon receiving this message, the pituitary releases two key gonadotropins ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones are the primary drivers of testicular function. LH travels to the Leydig cells in the testes, signaling them to produce testosterone, the principal male androgen.

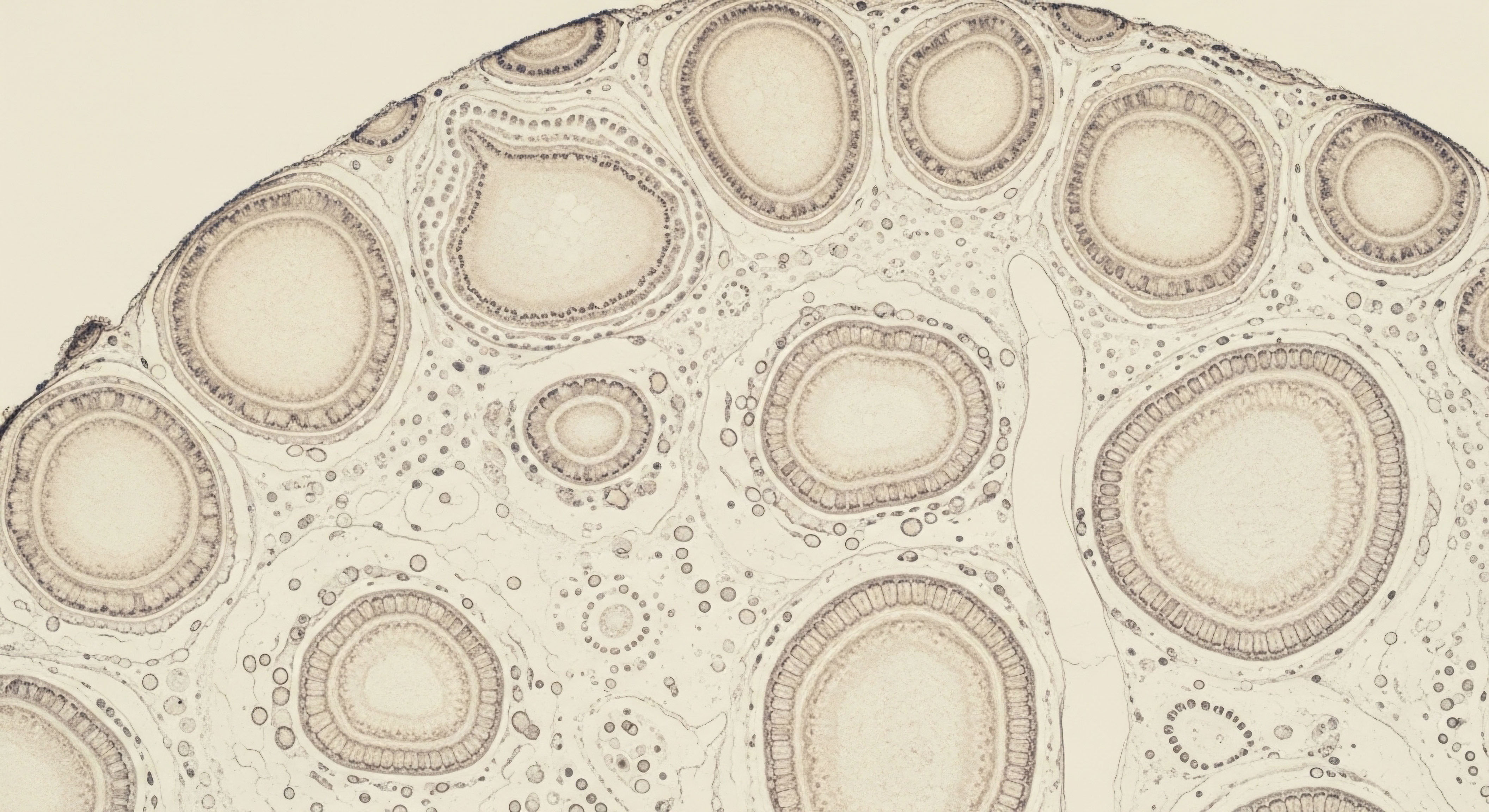

FSH acts on the Sertoli cells within the seminiferous tubules, structures that are the very nurseries of sperm production, a process known as spermatogenesis. The health and vitality of this entire axis is predicated on the clarity and rhythm of its internal communication, from the initial GnRH pulse to the final production of testosterone and sperm.

The Intersection of Stress and Reproduction

The connection between stress and infertility becomes clear when we understand that these two axes are not isolated. They are in a constant state of crosstalk. The hormones and neurotransmitters of the HPA axis can directly influence and, in cases of chronic activation, suppress the HPG axis.

Cortisol, the final product of the stress response, is a powerful modulator. When its levels are persistently elevated, it sends a powerful inhibitory signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary. This signal effectively tells the brain, “We are in a state of emergency; now is not the time to allocate resources to long-term projects like reproduction.”

This suppression occurs at multiple levels. Elevated cortisol can reduce the frequency and amplitude of GnRH pulses from the hypothalamus. This dampening of the initial signal means the pituitary gland receives a weaker and less coherent message, leading it to produce less LH and FSH.

Reduced LH output directly translates to lower testosterone production by the Leydig cells. This state, known as hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, is a condition where low testosterone is a result of a signaling problem from the brain. Reduced FSH levels impair the function of the Sertoli cells, disrupting the carefully orchestrated process of spermatogenesis.

The result is a potential decline in sperm count, motility (the ability of sperm to move effectively), and morphology (the proper shape and structure of sperm). The healthy lifestyle you cultivate provides the best possible raw materials for fertility, yet chronic stress can effectively shut down the factory that uses those materials.

What Is the Body Prioritizing?

From a biological perspective, this response is logical. In an ancestral environment, a state of chronic stress likely meant famine, war, or immediate physical danger. In such a context, procreation would be a poor allocation of metabolic resources. The body wisely prioritizes immediate survival over generational succession.

The cortisol-driven suppression of the reproductive axis is a primal adaptation designed to conserve energy for the present crisis. The difficulty in our modern world is that the “crisis” is often abstract, psychological, and unceasing. The brain does not distinguish between the stress of a predator and the stress of a toxic work environment; the HPA axis is activated all the same.

Your conscious mind understands that you are safe, but your physiology is behaving as if it is under constant threat. This creates a fundamental mismatch between your lived reality and your biological state, a mismatch that can manifest as unexplained infertility. Understanding this connection is the first step in reclaiming control, as it shifts the focus from a perceived personal failing to a tangible, systemic biological process that can be addressed and modulated.

Intermediate

To fully grasp how a state of mind can exert such a powerful influence over a physical process like fertility, we must examine the specific biochemical mechanisms that link the stress and reproductive systems. The interaction is a cascade of inhibitory signals, where the activation of the HPA axis actively applies a brake to the HPG axis.

This is a highly regulated process, a biological system of checks and balances that, when chronically engaged, leads to a significant downregulation of the entire male reproductive apparatus. The healthy lifestyle you maintain is critical, providing an optimal foundation, but it cannot always override a systemic hormonal suppression orchestrated from the highest levels of the central nervous system.

The Central Governor GnRH Pulse Disruption

The entire reproductive cascade begins with the pulsatile release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. The rhythm of these pulses is the master conductor of the symphony. Chronic stress introduces a powerful disruptive force. The key player here is Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH), the initiating hormone of the HPA axis.

CRH neurons are located in close proximity to GnRH neurons within the hypothalamus, and evidence suggests a direct inhibitory relationship. When CRH levels are high, they can suppress the activity of the GnRH neurons, slowing the frequency of their pulses.

Furthermore, the stress response floods the system with endogenous opioids, such as beta-endorphins. These molecules, known for their pain-reducing effects, also act directly on the hypothalamus to inhibit GnRH secretion. They are part of the body’s natural “shut down” mechanism during times of extreme stress.

Cortisol itself, the downstream product of the HPA axis, exerts a powerful negative feedback effect on the hypothalamus, further reducing GnRH output. This creates a three-pronged attack on the very source of the reproductive signal. The message from the brain to the testes becomes faint, irregular, and insufficient to maintain optimal function.

The suppression of male fertility by stress is a multi-layered process, beginning with the disruption of critical hormone-releasing signals within the brain.

The Pituitary and Gonadal Response

With a weakened GnRH signal arriving at the pituitary, the gland’s response is proportionally diminished. The production of both Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) decreases. This has direct and measurable consequences for the testes.

- LH and Testosterone Production LH is the direct stimulus for the Leydig cells in the testes to synthesize testosterone. When LH levels fall due to central suppression, testosterone production declines. Testosterone is the primary anabolic hormone in men, and its roles extend far beyond libido. It is essential for maintaining the health of the seminiferous tubules and supporting the complex, multi-stage process of sperm maturation. Without adequate testosterone, spermatogenesis can be arrested at various stages, leading to a lower concentration of mature, functional sperm.

- FSH and Sertoli Cell Function FSH is the primary driver of Sertoli cell function. These cells are often called the “nurse cells” of the testes because they provide the structural and nutritional support required for developing germ cells to mature into sperm. They create a specialized environment known as the blood-testis barrier, which protects the developing sperm from the body’s immune system. Reduced FSH levels compromise the ability of Sertoli cells to perform these functions, leading to a less supportive environment for spermatogenesis and potentially causing apoptosis (programmed cell death) of germ cells.

This state of centrally mediated low testosterone and impaired spermatogenesis is what clinicians refer to as hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. It is a condition where the gonads are healthy and capable of functioning, but they are not receiving the necessary hormonal stimulation from the brain.

Can This Be Addressed with Clinical Protocols?

Yes, understanding this mechanism allows for targeted interventions. For men whose infertility is linked to stress-induced HPG axis suppression, protocols are designed to restart the brain’s signaling. A Post-TRT or Fertility-Stimulating Protocol, for instance, uses medications that target specific points in this suppressed pathway.

A Comparison of Key Therapeutic Agents

| Medication | Mechanism of Action | Primary Goal in Fertility Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Gonadorelin | A synthetic form of GnRH. When administered in a pulsatile fashion, it mimics the natural rhythm of the hypothalamus. | To directly stimulate the pituitary gland to produce LH and FSH, bypassing the suppressed hypothalamus. |

| Clomiphene (Clomid) | A Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM). It blocks estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus, making the brain perceive lower estrogen levels. | To trick the hypothalamus into increasing GnRH production, thereby boosting the entire HPG axis. |

| Anastrozole | An Aromatase Inhibitor. It blocks the conversion of testosterone into estrogen in peripheral tissues. | To optimize the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio, which can further enhance the positive feedback to the brain. |

These protocols demonstrate a core principle of functional medicine ∞ if a system is suppressed, one can either remove the suppressor (in this case, manage the chronic stress) or directly stimulate the system downstream to restore its function. Often, the most effective approach involves doing both simultaneously.

The Role of Gonadotropin Inhibitory Hormone

A more recent discovery adds another layer of complexity to this system ∞ Gonadotropin-Inhibitory Hormone (GnIH). As its name suggests, GnIH acts as a direct antagonist to GnRH. It is produced in the hypothalamus and acts on both the hypothalamus and the pituitary to suppress the reproductive axis.

Research has shown that during times of stress, the expression of GnIH increases. This means the body produces a specific “brake” hormone for the reproductive system as part of the stress response. The activation of the HPA axis not only removes the “accelerator” (GnRH) but also applies this specific brake (GnIH), creating a powerful dual mechanism of suppression that ensures reproductive functions are halted during perceived emergencies.

This discovery underscores the profound and deeply embedded biological link between the experience of stress and the potential for fertility.

Academic

An academic exploration of stress-induced male infertility moves beyond the systemic hormonal dialogue of the HPA and HPG axes and into the cellular and molecular environment of the testis itself. While the suppression of gonadotropins is the primary upstream event, the downstream consequences manifest as a cascade of cytotoxic and disruptive processes within the testicular microenvironment.

A healthy lifestyle provides systemic resilience, yet the biochemical mediators of chronic stress, particularly glucocorticoids and catecholamines, can inflict direct cellular damage, compromise protective barriers, and induce a state of oxidative stress that is fundamentally hostile to the delicate process of spermatogenesis. The question becomes less about whether stress can cause infertility and more about the precise molecular pathologies it triggers within the gonadal tissue.

Glucocorticoid Receptor Activation and Testicular Apoptosis

The primary effector of the stress response, cortisol, exerts its influence by binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs). These receptors are expressed ubiquitously throughout the body, including on Leydig cells, Sertoli cells, and even the developing germ cells within the seminiferous tubules. The chronic saturation of these receptors by high levels of cortisol initiates a series of detrimental genomic and non-genomic actions.

Within Leydig cells, GR activation has been shown to directly inhibit the expression of key steroidogenic enzymes necessary for testosterone synthesis, such as P450scc (cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme) and 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase. This is a direct, localized suppression of androgenesis that is independent of the central suppression of LH.

It means that even if some LH manages to reach the testes, the Leydig cells themselves are functionally impaired in their ability to produce testosterone. This dual-hit hypothesis ∞ central LH suppression combined with local enzymatic inhibition ∞ explains the profound drop in testosterone often observed in states of chronic, severe stress.

Perhaps more destructively, persistent GR activation in germ cells triggers apoptotic pathways. Cortisol can increase the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins like Bax while decreasing the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2, tipping the cellular balance toward programmed cell death. This can lead to a significant depletion of the spermatogonial stem cell pool and the elimination of spermatocytes and spermatids at various stages of maturation, a condition clinically observed as maturation arrest in testicular biopsies.

Oxidative Stress and the Blood Testis Barrier

Spermatogenesis is a process that is exquisitely sensitive to oxidative stress. Developing sperm cells have limited cytoplasm and therefore a limited capacity for intrinsic antioxidant defense. Chronic psychological stress is a potent inducer of systemic oxidative stress.

The release of catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) during the stress response can increase metabolic rate and mitochondrial activity, leading to a greater production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) like superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. When antioxidant capacity is overwhelmed, these ROS inflict damage on critical cellular components.

Impact of Reactive Oxygen Species on Sperm

| Target | Mechanism of Damage | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm DNA | ROS can cause single- and double-strand breaks in the DNA of the sperm nucleus. The sperm’s highly compacted chromatin is particularly vulnerable. | Leads to high DNA Fragmentation Index (DFI), which is strongly correlated with failed fertilization, poor embryo development, and early pregnancy loss. |

| Cell Membrane | The sperm plasma membrane is rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are highly susceptible to lipid peroxidation by ROS. | Causes loss of membrane fluidity and integrity, impairing sperm motility and the ability to undergo the acrosome reaction required for fertilization. |

| Mitochondria | The mitochondria in the sperm midpiece, which power motility, can be damaged by ROS, leading to a decline in ATP production. | Results in asthenozoospermia (low sperm motility), as the sperm lack the energy to travel through the female reproductive tract. |

This oxidative assault is compounded by cortisol’s effect on the blood-testis barrier (BTB). The BTB, formed by tight junctions between adjacent Sertoli cells, creates an immunologically privileged site for spermatogenesis. Cortisol has been shown to increase the permeability of this barrier by downregulating the expression of key tight junction proteins like claudin-11 and occludin.

A compromised BTB allows for the infiltration of inflammatory cytokines and immune cells into the seminiferous tubules, further exacerbating the local inflammatory state and exposing the developing germ cells to immune attack, a condition akin to autoimmune orchitis.

What Are the Epigenetic Implications of Paternal Stress?

A frontier of research in this field is the study of epigenetics ∞ modifications to DNA that do not change the sequence itself but alter gene activity. Chronic stress has been demonstrated to induce epigenetic changes in sperm. Studies in animal models have shown that paternal stress can alter DNA methylation patterns and the profile of small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs) in sperm.

These epigenetic marks are transmitted to the zygote at fertilization and can influence the neurodevelopmental trajectory of the offspring. This suggests that the impact of paternal stress may extend beyond the individual’s own fertility, potentially programming a predisposition to stress-related disorders in the next generation.

This is a profound concept ∞ the father’s psychological state can be transcribed into a biochemical code that shapes the future health of his children. It elevates the management of stress from a matter of personal well-being to one of generational health.

In conclusion, the proposition that stress alone can be a primary cause of male infertility, even in the context of a healthy lifestyle, is not only plausible but supported by a robust body of scientific evidence at the systemic, cellular, and molecular levels.

The mechanism is a sophisticated and devastatingly effective biological strategy for survival, prioritizing the organism’s immediate safety over the long-term goal of procreation. It involves central neuroendocrine suppression, local enzymatic inhibition, induction of apoptosis, widespread oxidative damage, and the compromise of protective physiological barriers.

The clinical challenge is to address this deeply ingrained biological response in a world where the stressors are often chronic and psychological, requiring interventions that can either buffer the individual from the stressor or directly counteract its multifaceted pathological sequelae within the male reproductive system.

References

- Jóźków, P. & Mędraś, M. (2012). Psychological stress and the function of male gonads. Endokrynologia Polska/Polish Journal of Endocrinology, 63(1), 44-49.

- Nargund, V. H. (2015). Effects of psychological stress on male fertility. Nature Reviews Urology, 12(7), 373-382.

- Bhuiyan, M. M. et al. (2022). Impact of stress on male fertility ∞ role of gonadotropin inhibitory hormone. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13, 934332.

- Ilacqua, A. et al. (2018). The role of stress in male and female reproduction ∞ a narrative review. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 16(1), 114.

- Du Plessis, S. S. et al. (2015). The effect of psychosocial stress on semen quality. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine, 61(5), 266-271.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a biological blueprint, a map that connects an internal feeling to a physiological outcome. It translates the abstract weight of stress into a concrete cascade of hormones, cellular responses, and measurable effects on fertility. This knowledge is a powerful tool.

It shifts the narrative from one of personal deficit to one of systemic imbalance. The path forward begins with this understanding. Your body is not failing; it is responding exactly as it was designed to, albeit to a threat that is modern and persistent.

The journey to reclaiming your fertility, therefore, involves learning to manage this ancient biological response in the context of your contemporary life. What are the sources of signal noise in your world? How can you begin to build systems, both internal and external, that buffer your physiology from this chronic state of alarm?

This knowledge is the starting point, empowering you to ask more precise questions and seek more targeted support, transforming a feeling of helplessness into a proactive stance on your own health and future.

Glossary

hpa axis

pituitary gland

cortisol

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

hpg axis

leydig cells

spermatogenesis

sertoli cells

stress response

hypogonadotropic hypogonadism

healthy lifestyle

chronic stress

developing germ cells

sertoli cell function

hpg axis suppression

gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone

oxidative stress

germ cells