Fundamentals

You have embarked on a significant step in your personal health architecture, beginning a protocol for hormonal optimization. You’ve had the consultations, reviewed the lab work, and understood the clinical rationale. The expectation is a restoration of vitality, a return to a state of high function.

Yet, you may be experiencing a dissonance between that expectation and your current reality. Perhaps it presents as persistent bloating, a subtle but unshakable fluid retention, shifts in your mood that feel disconnected from your circumstances, or changes in body composition that seem counterintuitive to the therapy’s purpose.

This experience is a valid and vital piece of data. It is your body communicating its process of adaptation to a new biochemical environment. The path forward involves a partnership with your protocol, and your most powerful ally in this collaboration is the food you consume. Specific dietary patterns are the tools you use to fine-tune your body’s response to therapy, transforming it from a passive treatment into an active process of recalibration.

The science of endocrinology shows us that hormones are messengers, and the food we eat provides the raw materials for these messages, the pathways for their transmission, and the systems for their eventual clearance. When you introduce therapeutic hormones, you are changing the volume and frequency of these messages.

Your body must learn to process this new level of information. A strategic dietary approach provides the necessary support for this adaptation. It is about supplying the precise biological resources your system requires to integrate these new instructions efficiently and effectively.

The Core Components of a Supportive Diet

Understanding the function of macronutrients within the context of hormonal therapy is the first principle of building a supportive nutritional foundation. Each component has a distinct and crucial role in ensuring your protocol delivers its intended benefits while minimizing adjustments your body must make.

Protein the Structural Foundation

Adequate protein intake is fundamental when undergoing hormonal optimization. Therapeutic testosterone, for instance, signals the body to increase muscle protein synthesis. Failing to provide sufficient dietary protein is like asking a construction crew to build a skyscraper without supplying enough steel and concrete.

The body requires a consistent influx of amino acids, the building blocks of protein, to repair tissue, maintain lean body mass, and support metabolic rate. Aiming for a significant portion of protein with every meal sends a clear signal to your body to utilize the hormonal messages for anabolic, tissue-building purposes. This practice directly supports one of the primary goals of many hormonal protocols which is improved body composition and metabolic health.

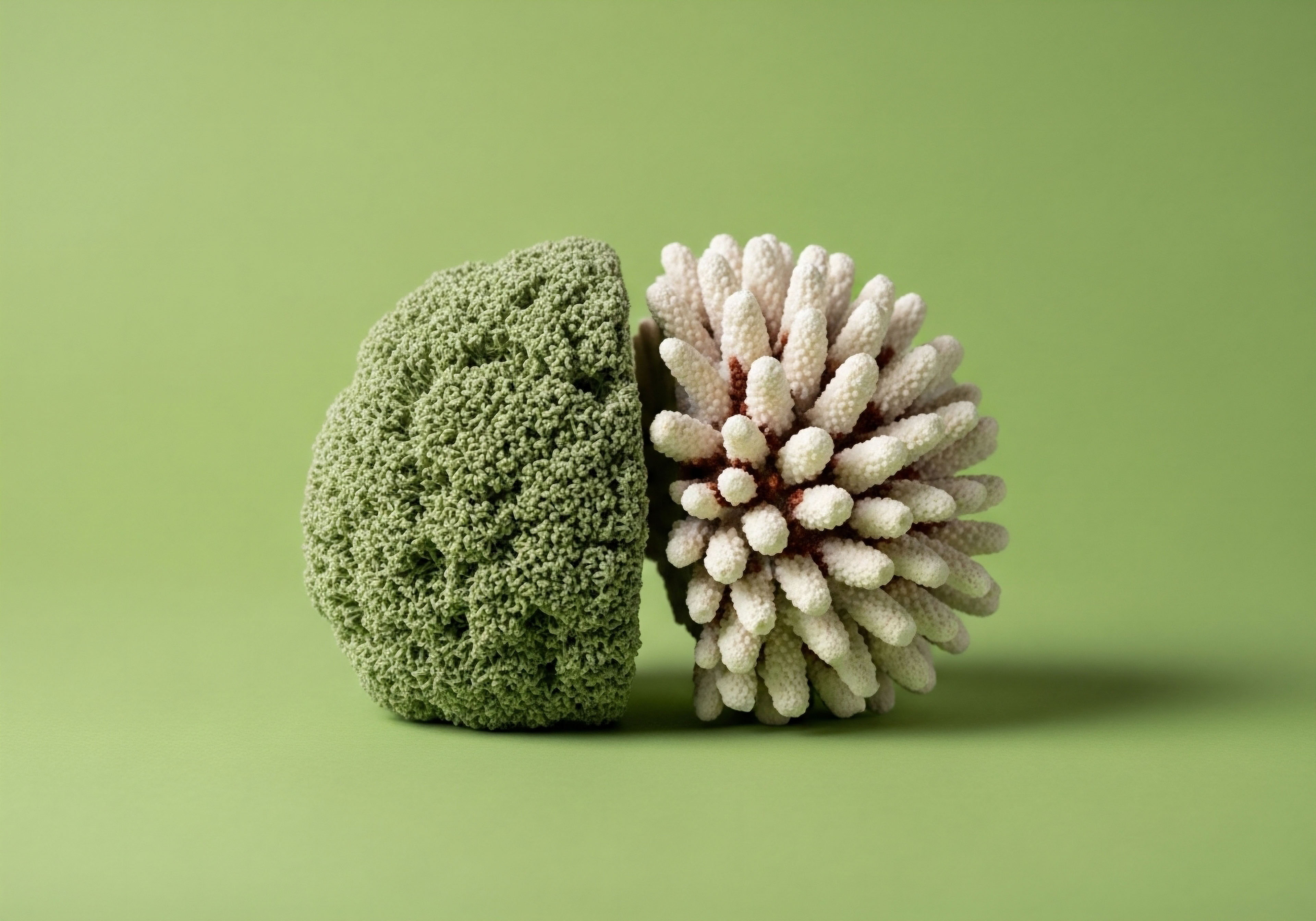

A diet rich in high-quality protein provides the essential building blocks your body needs to effectively utilize hormonal signals for muscle synthesis and metabolic stability.

Fats the Endocrine Raw Material

Healthy fats are the precursors from which steroid hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, are synthesized. Cholesterol, often viewed negatively, is the foundational molecule for this entire class of hormones. A diet that incorporates a rich supply of healthy fats from sources like avocados, olive oil, nuts, and fatty fish provides the essential substrates for your body’s own endocrine processes.

These fats also play a powerful role in modulating inflammation. Omega-3 fatty acids, in particular, help to create a less inflammatory internal environment, which can soothe some of the cellular stress that may accompany shifts in hormonal balance. This creates a more stable and receptive state for your body to adapt to therapy.

Fiber the Great Regulator

Fiber’s role in a hormone-supportive diet is perhaps one of the most vital and often overlooked. Its primary function in this context is to support the healthy metabolism and excretion of hormones, particularly estrogen. The digestive tract is a major site of hormone processing and elimination.

Soluble and insoluble fiber from vegetables, fruits, and whole grains ensures regular bowel motility, which is the primary route for excreting metabolized hormones. An efficient excretion system prevents these metabolites from re-entering circulation, a situation that can contribute to side effects like bloating and mood volatility. A high-fiber diet is a direct investment in a clean and efficient hormonal signaling environment.

By viewing your diet through this functional lens, you begin to see food as a set of instructions you provide to your body. These instructions can either complement or conflict with the signals from your therapeutic protocol. The objective is to create a state of biochemical congruence, where your diet and your therapy are working in unison toward the shared goal of optimal function and well-being.

| Food Group | Primary Role in Supporting HRT | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Lean Proteins | Provide amino acids for muscle synthesis and metabolic health. | Chicken breast, fish, lean beef, lentils, tofu, eggs. |

| Healthy Fats | Supply precursors for hormone production and modulate inflammation. | Avocado, olive oil, nuts, seeds, fatty fish (salmon, mackerel). |

| High-Fiber Carbohydrates | Regulate blood sugar and support hormone excretion via the gut. | Leafy greens, cruciferous vegetables, berries, quinoa, oats. |

| Cruciferous Vegetables | Support liver detoxification pathways for hormone metabolites. | Broccoli, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts. |

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational principles, we can now examine the specific biological mechanisms through which dietary choices can directly address the common side effects associated with hormonal therapies. When you begin a protocol like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), you are not just increasing testosterone; you are initiating a cascade of downstream metabolic events.

Understanding these pathways allows for a highly targeted nutritional strategy. Side effects such as water retention, moodiness, or skin issues are signals of specific physiological processes that can be modulated. Your diet becomes a sophisticated tool for managing these processes, ensuring a smoother and more effective therapeutic course.

How Does Diet Influence Estrogen Metabolism?

A central aspect of managing TRT in both men and women is controlling the conversion of testosterone to estrogen, a process mediated by the enzyme aromatase. While a certain level of estrogen is vital for health in both sexes, an excessive or imbalanced level can lead to side effects. Diet plays a profound role in how the body processes and eliminates estrogen, primarily through two key systems the liver and the gut.

Supporting Hepatic Detoxification

Your liver is the primary site for metabolizing hormones. It deactivates them through a two-phase process to prepare them for excretion.

- Phase I Detoxification This phase involves a group of enzymes known as cytochrome P450 that begin to break down estrogen.

- Phase II Detoxification This phase, particularly the glucuronidation pathway, attaches a molecule to the estrogen metabolite, making it water-soluble and ready for elimination through urine or bile.

Cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, cauliflower, and kale are exceptionally valuable here.

They contain compounds such as indole-3-carbinol (I3C) and diindolylmethane (DIM), which have been shown to support healthy Phase I and Phase II detoxification pathways. By promoting a more efficient clearance of estrogen metabolites, these foods help maintain a healthy testosterone-to-estrogen ratio, potentially mitigating side effects related to estrogen dominance.

The Estrobolome Your Gut’s Role in Hormone Balance

What happens after the liver processes estrogen is just as important. The conjugated estrogen metabolites are sent to the gut via bile for excretion. Here, they encounter the estrobolome, a collection of gut bacteria that produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase.

This enzyme can effectively “un-package” or deconjugate the estrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed back into the bloodstream. A diet low in fiber and high in processed foods can lead to an overgrowth of bacteria that produce high levels of beta-glucuronidase.

This creates a cycle of estrogen reabsorption known as enterohepatic circulation, which can undermine the liver’s hard work and contribute to an overall higher estrogen load. Conversely, a diet rich in fiber from diverse plant sources nourishes a healthy gut microbiome that keeps beta-glucuronidase activity in check. This ensures that once the liver has processed estrogen, it stays processed and is efficiently removed from the body.

A high-fiber diet directly supports the gut microbiome in preventing the reabsorption of estrogen metabolites, which is a key factor in maintaining hormonal equilibrium during therapy.

Managing Inflammation and Fluid Balance

Some individuals on hormonal protocols experience an increase in inflammation or fluid retention. This can be related to shifts in electrolyte balance and inflammatory signaling pathways. A targeted dietary approach can provide significant relief.

The Omega-3 and Omega-6 Balance

Polyunsaturated fats are essential, but their balance is what matters. Omega-6 fatty acids, prevalent in processed vegetable oils and packaged foods, tend to be pro-inflammatory. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, flaxseeds, and walnuts, are anti-inflammatory. A standard Western diet often has a ratio heavily skewed towards omega-6.

During hormonal therapy, when the body is already in a state of adaptation, this inflammatory background can be amplified. Shifting the dietary balance by increasing omega-3 intake and reducing processed omega-6 sources can help modulate this inflammatory response, potentially easing joint discomfort and reducing systemic stress.

The Sodium-Potassium Axis

Fluid retention is often a matter of electrolyte balance. Aldosterone, a hormone that regulates blood pressure and fluid balance, can be influenced by hormonal shifts. A diet high in sodium and low in potassium encourages the body to retain water. Sodium is abundant in processed foods, canned goods, and restaurant meals.

Potassium, which has the opposite effect of promoting fluid excretion, is rich in whole plant foods like leafy greens, bananas, and avocados. By consciously reducing processed sodium and increasing potassium-rich whole foods, you can support your body’s natural mechanisms for maintaining fluid homeostasis, reducing bloating and swelling.

| Symptom/Side Effect | Underlying Mechanism | Targeted Dietary Strategy | Key Foods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen Dominance (Moodiness, Bloating) | Inefficient estrogen metabolism and clearance. | Support liver detoxification and promote gut excretion. | Broccoli, kale, cauliflower, high-fiber grains, legumes. |

| Inflammation (Joint Pain, Fatigue) | Imbalance of pro- and anti-inflammatory fatty acids. | Increase omega-3 intake and reduce omega-6 intake. | Salmon, mackerel, sardines, flaxseeds, walnuts, olive oil. |

| Fluid Retention | Imbalance in the sodium-potassium electrolyte system. | Decrease processed sodium and increase dietary potassium. | Leafy greens, avocados, bananas, sweet potatoes, beans. |

| Poor Insulin Sensitivity | Hormonal influence on glucose metabolism. | Prioritize protein and fiber; manage carbohydrate timing. | Lean meats, fish, eggs, non-starchy vegetables, berries. |

Academic

A sophisticated application of nutritional science to hormonal optimization protocols requires a deep understanding of the interconnectedness of endocrine, metabolic, and gastrointestinal physiology. The clinical objective extends beyond simple symptom management to the strategic modulation of specific biochemical pathways.

When a patient initiates a therapy such as TRT, with or without an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole, or peptide therapies like Sermorelin, the intervention creates a new physiological state. The efficacy and tolerability of this state are profoundly influenced by the nutritional micro-environment. We will now examine the molecular interplay between dietary components and key enzymatic and microbial systems that govern hormone pharmacodynamics and metabolic outcomes.

Phytoestrogens a Molecular Perspective on Receptor Modulation

The conversation around plant-based compounds that interact with estrogen receptors (ERs) is often oversimplified. Phytoestrogens, such as the isoflavones found in soy (genistein, daidzein) and lignans in flaxseed, are not direct hormonal agonists in the same way as estradiol. Their clinical significance lies in their nature as Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs).

The human body has two primary types of estrogen receptors ER-alpha (ERα) and ER-beta (ERβ), which are distributed differently throughout tissues and often have opposing effects. ERα activation is typically associated with proliferative effects in tissues like the breast and uterus, while ERβ activation is often anti-proliferative and protective.

Many phytoestrogens exhibit a preferential binding affinity for ERβ. This means that in a high-estrogen environment, they can competitively bind to ERs, potentially blocking the action of more potent endogenous estrogens. In a low-estrogen environment, their weak agonistic activity at the ERβ receptor can provide a baseline level of beneficial signaling.

For a male patient on TRT concerned with managing the effects of aromatization, a diet rich in lignans may support a more favorable estrogenic balance by modulating receptor activity, independent of simply lowering total estrogen levels.

This SERM-like activity is a clear example of how diet can work synergistically with a protocol. While Anastrozole works by inhibiting the aromatase enzyme to reduce the production of estrogen, dietary phytoestrogens work at the receptor level to modulate the effects of the estrogen that is present. This creates a multi-pronged approach to achieving hormonal homeostasis.

The Gut-Liver Axis and Glucuronidation a Deeper Analysis

The process of glucuronidation, a cornerstone of Phase II liver detoxification, is the primary mechanism for neutralizing and preparing steroid hormones for excretion. The enzyme UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) attaches glucuronic acid to estrogen, rendering it inactive and water-soluble. The efficiency of this process can be influenced by nutritional cofactors.

However, the true vulnerability of this pathway lies in the gut. The deconjugating activity of bacterial beta-glucuronidase essentially reverses the liver’s work. High levels of this enzyme, associated with a dysbiotic gut microbiome often resulting from a low-fiber, high-sugar diet, can significantly increase the enterohepatic recirculation of estrogens. This leads to a greater total systemic exposure to estrogen, which can manifest as side effects and necessitate higher doses of aromatase inhibitors.

The enzymatic activity within the gut microbiome, specifically beta-glucuronidase levels, is a critical determinant of net systemic estrogen exposure and a primary target for dietary intervention.

A diet specifically designed to mitigate this effect would be rich in soluble and insoluble fiber. Soluble fiber acts as a prebiotic, feeding beneficial bacteria that lower the gut pH and inhibit the growth of beta-glucuronidase-producing species. Insoluble fiber increases fecal bulk and accelerates transit time, reducing the window of opportunity for deconjugation and reabsorption to occur.

Therefore, a prescription for a high-fiber diet is a clinical tool to decrease enterohepatic circulation and support the efficacy of the primary hormonal protocol.

- Lignans Found in flaxseeds, sesame seeds, and whole grains, these are converted by gut bacteria into enterolactone and enterodiol, compounds with weak estrogenic and anti-estrogenic effects.

- Isoflavones Present in soy products, these are metabolized by the gut microbiome into compounds like equol, which has a higher binding affinity for ERβ. The ability to produce equol is dependent on having the right gut bacteria, highlighting the synergy between diet and microbiome.

- Glucosinolates Found in cruciferous vegetables, these are hydrolyzed to isothiocyanates like sulforaphane, which are potent inducers of Phase II detoxification enzymes in the liver, enhancing the initial clearance of hormones.

This systems-biology perspective reveals that diet is not merely supportive; it is an active modulator of the very pathways that determine therapeutic success. For the clinician, prescribing a dietary pattern rich in fiber and phytoestrogens is as logical as prescribing the hormone itself, as it addresses the metabolic fate of the therapeutic agent.

How Does Diet Impact Peptide Therapy Outcomes?

Peptide therapies, such as the use of Growth Hormone Releasing Hormones (GHRHs) like Sermorelin or CJC-1295, are designed to stimulate the patient’s own pituitary gland. The efficacy of this stimulation depends on a well-functioning hypothalamic-pituitary axis and stable background metabolic health.

Insulin resistance, a condition driven by diets high in refined carbohydrates and sugars, creates a state of metabolic noise that can interfere with hormonal signaling. High circulating insulin levels can blunt the growth hormone response to GHRH stimulation.

Therefore, a dietary pattern that promotes insulin sensitivity, such as a Mediterranean-style or low-glycemic index diet, is essential for maximizing the benefits of peptide therapy. This dietary approach, rich in protein, healthy fats, and fiber, ensures that the pituitary can respond robustly to the peptide’s signal, leading to more effective and predictable outcomes in terms of body composition, recovery, and overall vitality.

References

- Ramsay, R. (2025). How HRT Affects Your Diet and Nutrition ∞ Managing Your Eating Habits While on Hormone Therapy.

- Hill, A. M. & Ward, E. J. (2023). The role of diet in managing menopausal symptoms ∞ A narrative review. Nutrition Bulletin, 48(4), 473-499.

- Reisig, M. & Woods, J. (2019). Please discuss what foods should be included or excluded from the diet for women who do not take hormone replacement therapy (HRT). University of Rochester Medical Center.

- Le-Ha, C. et al. (2011). Differential Dietary Nutrient Intake according to Hormone Replacement Therapy Use ∞ An Underestimated Confounding Factor in Epidemiologic Studies?. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174(1), 57-65.

- Kubala, J. (2023). 10 Natural Ways to Balance Your Hormones. Healthline.

Reflection

You have now seen the intricate biological connections between your hormonal protocol and your nutritional choices. The information presented here is a map, showing the pathways and systems at play within your own body. It demonstrates that your daily decisions at the dinner table are a form of dialogue with your physiology.

This knowledge shifts the paradigm from being a passive recipient of a therapy to an active participant in your own wellness architecture. The true power of this understanding is not in its complexity, but in its application.

Where Do You Begin Your Dialogue?

Consider the communication you have been receiving from your body. Is it speaking through bloating, fatigue, or a subtle shift in your mood? These are not mere side effects to be tolerated; they are data points inviting a response. What is the single most resonant concept you have encountered here?

Is it the role of fiber in clearing old hormones, the anti-inflammatory power of omega-3 fats, or the liver-supporting function of cruciferous vegetables? The next step on your journey is not to overhaul everything at once. It is to choose one area, one single meal, one conscious dietary decision, and begin the conversation.

Your path to optimized health is a process of continuous, informed adjustments. This knowledge is your first tool in that process. The next is listening to the results.

Glossary

fluid retention

healthy fats

omega-3 fatty acids

side effects

testosterone replacement therapy

cytochrome p450

glucuronidation

cruciferous vegetables

beta-glucuronidase

estrobolome

enterohepatic circulation

gut microbiome

fatty acids

anastrozole

selective estrogen receptor modulators

phytoestrogens