Fundamentals

You feel it the morning after. It is a familiar sense of being physically and mentally out of sync. The fatigue sinks deeper than simple tiredness, your mood feels untethered, and your mind is clouded. You might attribute this to dehydration or poor sleep, and you would be partially right.

These feelings, however, are also the perceptible echoes of a profound, silent conversation being disrupted deep within your body. This conversation, orchestrated by your endocrine system, is the very foundation of your vitality, and alcohol is a primary interferent in its elegant transmission. Understanding this interference is the first step toward reclaiming your biological command.

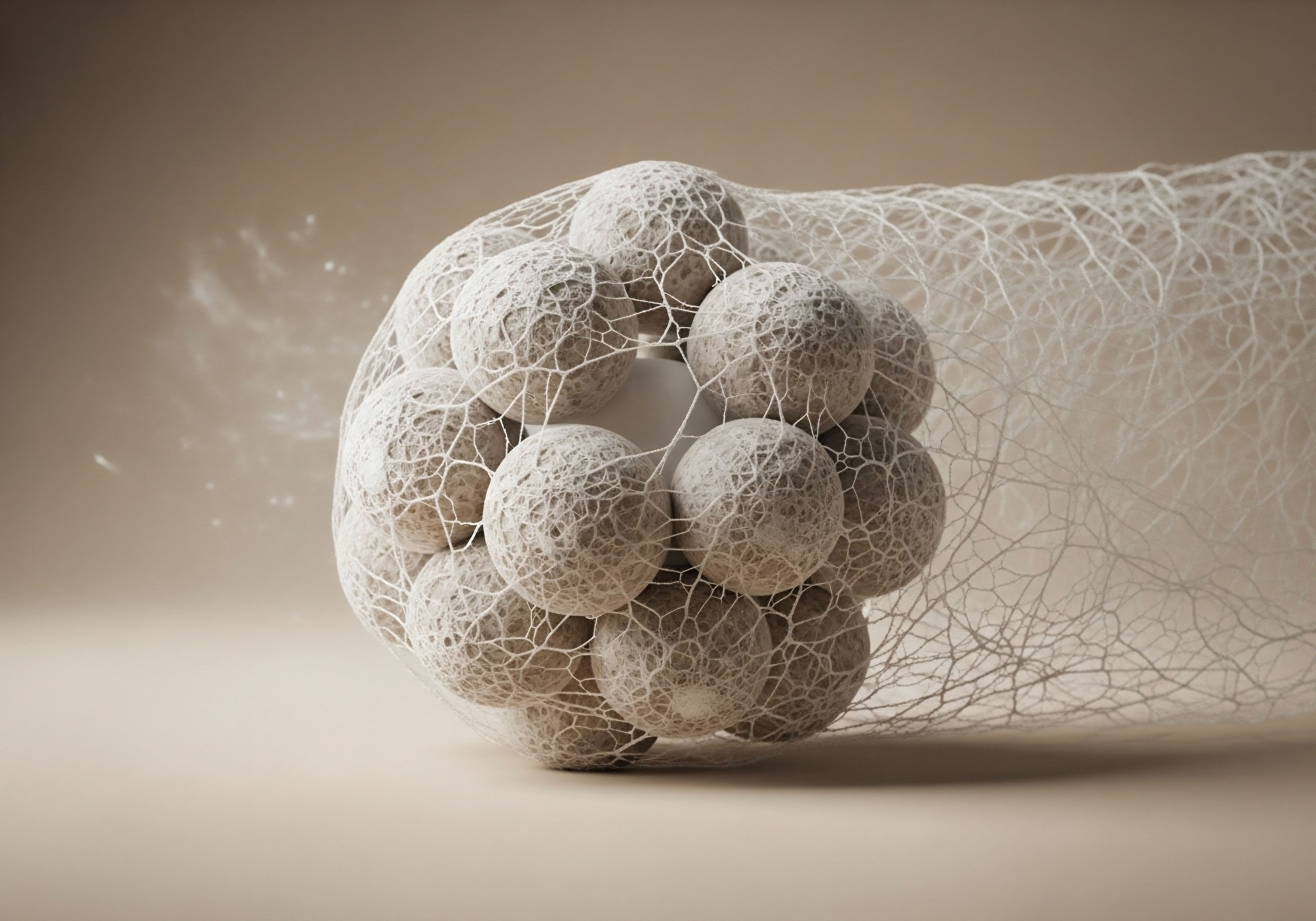

Your body operates as a sophisticated communication network. The endocrine system is its internal messaging service, using chemical messengers called hormones to regulate everything from your energy levels and mood to your reproductive health and stress response. These hormones travel through your bloodstream, delivering precise instructions to target cells, ensuring your internal environment remains stable and functional.

Think of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis as the central command tower for your reproductive and hormonal health. The hypothalamus sends a signal to the pituitary gland, which in turn signals the gonads (testes in men, ovaries in women) to produce the primary sex hormones. It is a finely tuned feedback loop, a constant flow of information designed to maintain equilibrium.

When you introduce alcohol, you introduce a systemic disruptor. Ethanol, the active compound in alcoholic beverages, is a toxin that your body must prioritize metabolizing. This metabolic priority comes at a cost, diverting resources and directly interfering with the endocrine system’s communication channels. The command tower, your HPG axis, experiences this interference acutely.

The signals become garbled, delayed, or missed entirely. This disruption is not a vague concept; it is a measurable physiological event with direct consequences on how you feel and function.

The Key Hormonal Players and Their Roles

To appreciate the depth of this disruption, it is helpful to understand the key players involved. These hormones are responsible for much of what defines your daily experience of health and well-being.

- Testosterone ∞ In both men and women, testosterone is integral to maintaining muscle mass, bone density, libido, and a sense of vitality and motivation. Its decline is often associated with fatigue, reduced drive, and changes in body composition.

- Estrogen ∞ While primarily known as a female sex hormone crucial for regulating the menstrual cycle and reproductive health, estrogen also plays a role in male health, contributing to erectile function and sperm maturation. Balance is the operative word, as excesses or deficiencies in either sex lead to dysfunction.

- Cortisol ∞ Known as the primary stress hormone, cortisol is released in response to perceived threats. It is essential for survival, heightening awareness and mobilizing energy. Chronic elevation, however, becomes corrosive to the body, suppressing immune function, breaking down muscle tissue, and directly interfering with the production of sex hormones like testosterone.

Alcohol consumption directly impacts the balance of these critical hormones. It acts as a physiological stressor, triggering the release of cortisol. This elevation of cortisol creates a competitive environment within your body, where the resources needed to produce testosterone are reallocated to manage the stress response initiated by the alcohol.

The result is a direct suppression of testosterone production, a phenomenon that can be observed even after a single episode of heavy drinking. This biochemical shift contributes significantly to the next-day feelings of lethargy and diminished drive.

The fatigue and mood shifts after drinking are direct signals of alcohol’s interference with your body’s essential hormonal communication network.

The impact extends beyond a single day. Chronic alcohol consumption establishes a new, dysfunctional baseline. The body adapts to the regular presence of this toxin, leading to sustained hormonal imbalances. In men, this can manifest as consistently lower testosterone levels and elevated estrogen, a combination that accelerates the loss of muscle mass and promotes fat storage, particularly around the midsection.

In women, chronic alcohol use can disrupt the delicate rhythm of the menstrual cycle, interfere with fertility, and exacerbate mood swings.

This information provides a powerful framework for understanding your own body. The symptoms you experience are not isolated events; they are data points reflecting an underlying systemic disruption. This perspective shifts the narrative from one of passive endurance to one of active engagement.

While alcohol is a potent endocrine disruptor, your body is a dynamic and resilient system. Through targeted nutritional strategies and intentional lifestyle adjustments, you can support its innate capacity for balance and repair. You can provide the raw materials it needs to fortify its communication channels, process toxins efficiently, and restore the hormonal equilibrium that is the bedrock of your health. This is a journey of biological reclamation, and it begins with understanding the system you wish to support.

Intermediate

To effectively counteract alcohol’s impact on your hormonal health, we must move beyond a general understanding and examine the specific biological mechanisms at play. The conversation between your brain and your gonads, mediated by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, is where the most significant disruption occurs.

This is a system of elegant precision, and alcohol acts as a blunt force, creating static on a clear channel. By understanding precisely how this static is generated, we can develop targeted strategies to restore the signal.

The HPG axis functions through a negative feedback loop. The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which instructs the pituitary gland to secrete Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). LH is the primary signal for the Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone.

As testosterone levels rise, they send a signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to slow down GnRH and LH production, maintaining a stable hormonal environment. Alcohol directly sabotages this communication at multiple points. Chronic exposure can suppress the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus, effectively silencing the initial command. This leads to reduced LH secretion from the pituitary, starving the testes of the very signal they need to function.

How Does Alcohol Directly Suppress Testosterone Production?

The reduction in testosterone following alcohol consumption is not solely due to central signaling disruption. Alcohol exerts a direct toxic effect on the testes themselves, further compromising their ability to synthesize this vital hormone. This multi-pronged assault is why the impact can be so pronounced and persistent.

One of the primary mechanisms is the direct damage to Leydig cells. These cells are the testosterone factories of the body, and ethanol is cytotoxic to them. Heavy or chronic alcohol use triggers inflammation and oxidative stress within the testicular tissue, impairing the function of these crucial cells and reducing their capacity to produce testosterone.

Simultaneously, alcohol elevates the body’s stress response, flooding the system with cortisol. Cortisol and testosterone have an antagonistic relationship; elevated cortisol levels directly inhibit testosterone synthesis. This creates a physiological state where the body is actively suppressing its own anabolic, vitality-promoting hormones in favor of a catabolic, stress-driven state.

The Aromatase Connection

A further complication is alcohol’s effect on the aromatase enzyme. Aromatase is responsible for converting androgens, like testosterone, into estrogens. While this is a normal and necessary process for maintaining hormonal balance, alcohol significantly increases aromatase activity, particularly in the liver. This accelerated conversion has two detrimental effects.

First, it directly reduces the amount of available free testosterone in the bloodstream. Second, it increases levels of estradiol, the primary estrogen. In men, this hormonal shift can lead to unwanted feminizing effects, such as the development of breast tissue (gynecomastia), increased body fat, and a further suppression of the HPG axis, as elevated estrogen signals the brain to shut down testosterone production. In women, elevated estrogen levels can worsen conditions like endometriosis and contribute to heavier, more painful menstrual cycles.

| Hormone | Acute Effect (Single Heavy Use) | Chronic Effect (Sustained Heavy Use) |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone |

Significant temporary decrease, lasting up to 48 hours. |

Sustained suppression (hypogonadism), testicular atrophy. |

| Estrogen (Estradiol) |

Temporary increase due to aromatization. |

Chronically elevated levels, contributing to feminization in men and cycle disruption in women. |

| Cortisol |

Sharp increase, promoting a catabolic state. |

Dysregulated HPA axis, leading to chronically high basal cortisol and adrenal dysfunction. |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) |

Suppressed release from the pituitary gland. |

Persistently low levels due to suppressed GnRH and negative feedback from high estrogen. |

Building Resilience through Personalized Nutrition

Understanding these mechanisms allows us to move from diagnosis to action. A personalized nutrition strategy can provide the specific biochemical tools your body needs to defend against and repair the damage caused by alcohol. This approach focuses on supporting the organs most affected ∞ the liver and the gut.

The liver is the primary site of alcohol detoxification and hormone metabolism. When burdened with processing ethanol, its ability to perform other vital functions, like clearing excess estrogen, is compromised. Supporting the liver’s detoxification pathways is therefore a critical intervention. This involves ensuring an adequate supply of key micronutrients that act as cofactors for detoxification enzymes. Nutrients like B vitamins (especially B12 and folate), zinc, and magnesium are rapidly depleted by alcohol consumption and are essential for these processes.

Targeted nutrition directly supports the liver and gut, reinforcing the very systems that alcohol compromises.

Perhaps even more fundamental is addressing the impact of alcohol on the gut microbiome. Alcohol consumption promotes gut dysbiosis, an imbalance in the trillions of bacteria residing in your digestive tract. This leads to a condition known as increased intestinal permeability, or “leaky gut,” where the tight junctions lining the intestines become compromised.

This allows bacterial toxins to leak into the bloodstream, triggering a state of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation that further disrupts hormonal signaling and burdens the liver. Restoring the integrity of the gut lining and rebalancing the microbiome is a foundational step in mitigating alcohol’s effects.

- Zinc ∞ This mineral is crucial for testosterone production and for maintaining the integrity of the gut lining. Alcohol both inhibits its absorption and increases its excretion. Replenishing zinc through foods like oysters, red meat, and pumpkin seeds is essential.

- B Vitamins ∞ Particularly folate (B9) and cobalamin (B12), these are vital for the liver’s methylation processes, which are necessary for detoxifying alcohol and metabolizing estrogen. Alcohol severely depletes these nutrients. Leafy greens, legumes, and eggs are excellent sources.

- Magnesium ∞ Involved in over 300 enzymatic reactions, magnesium is critical for sleep quality, stress regulation, and insulin sensitivity. Alcohol consumption leads to significant urinary loss of magnesium. Nuts, seeds, and dark chocolate can help restore levels.

- Antioxidants ∞ Compounds like N-acetylcysteine (NAC), vitamin C, and selenium help to quench the oxidative stress generated by alcohol metabolism, protecting cells in the testes and liver from damage.

Lifestyle Adjustments for Hormonal Stability

Nutritional interventions are powerfully amplified by specific lifestyle adjustments. Strategic resistance training, for instance, is a potent stimulus for testosterone production and improves insulin sensitivity, directly counteracting two of alcohol’s negative metabolic consequences. Prioritizing sleep is equally important.

Alcohol severely fragments sleep architecture, particularly REM sleep, and suppresses the nocturnal release of growth hormone, a key player in tissue repair and metabolic health. Implementing a consistent sleep schedule, creating a dark and cool sleep environment, and avoiding alcohol close to bedtime can help restore these vital restorative processes.

By combining a deep understanding of the biochemical disruption with targeted nutritional and lifestyle support, you can construct a robust, personalized protocol to mitigate the impact of alcohol and preserve your hormonal vitality.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of alcohol’s endocrine disruption requires us to look beyond isolated hormonal effects and adopt a systems-biology perspective. The hormonal dysregulation observed is not merely a collection of individual consequences but the downstream result of a primary insult ∞ the compromising of the gut-liver-brain axis.

Specifically, alcohol-induced gut dysbiosis and the resultant endotoxemia function as the origin point for a cascade of systemic inflammation that fundamentally alters endocrine function at the hypothalamic, pituitary, and gonadal levels. Mitigating alcohol’s impact, therefore, necessitates an intervention strategy that targets the integrity of the intestinal barrier and modulates the inflammatory response.

The gut microbiome is increasingly understood as a critical endocrine organ, capable of synthesizing and modulating a vast array of bioactive compounds, including neurotransmitters and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), that influence host physiology. Chronic alcohol consumption profoundly alters the composition of this microbial community, reducing beneficial butyrate-producing species like Faecalibacterium and increasing the prevalence of gram-negative bacteria.

This state of dysbiosis has two primary pathological consequences. First, the reduction in butyrate deprives colonocytes of their primary energy source, weakening the intestinal barrier. Second, the overgrowth of gram-negative bacteria increases the luminal load of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a potent inflammatory endotoxin found in their outer membrane.

From Gut Permeability to Systemic Inflammation

The combination of a weakened barrier and high LPS load facilitates the translocation of this endotoxin from the gut lumen into the portal circulation and, subsequently, the systemic bloodstream. This condition, known as metabolic endotoxemia, is a key driver of the chronic, low-grade inflammation that underpins many modern metabolic diseases.

Circulating LPS binds to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on immune cells, particularly macrophages like the liver’s Kupffer cells, triggering a potent inflammatory cascade. This activation results in the sustained production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are the primary mediators of alcohol’s distant effects on the endocrine system.

| Cytokine | Primary Source | Mechanism of Endocrine Disruption |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) |

Kupffer cells and other macrophages activated by LPS. |

Directly suppresses Leydig cell steroidogenesis by inhibiting key enzymes like P450scc. Induces insulin resistance in peripheral tissues. Suppresses GnRH neuron activity in the hypothalamus. |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) |

Immune cells, adipose tissue, endothelial cells. |

Stimulates the HPA axis, leading to increased cortisol production which suppresses the HPG axis. Can contribute to aromatase expression in adipose tissue. |

| Interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) |

Monocytes, macrophages, microglia in the brain. |

Potent suppressor of GnRH release. Contributes to neuroinflammation, affecting pituitary sensitivity to GnRH. Implicated in the sickness behavior associated with hangovers and chronic alcohol use. |

This inflammatory state creates a hostile environment for normal endocrine function. In the testes, TNF-α has been shown to directly inhibit testosterone synthesis in Leydig cells. In the brain, cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α can cross the blood-brain barrier or be produced locally by microglia, leading to neuroinflammation.

This neuroinflammatory state directly suppresses the activity of GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus, representing a central, inflammation-driven shutdown of the entire HPG axis. This mechanism provides a unifying explanation for how a gut-level disturbance can manifest as clinical hypogonadism.

What Are the Broader Metabolic Consequences?

The systemic inflammation driven by endotoxemia extends its disruptive influence to metabolic regulation, creating a vicious cycle that further degrades hormonal health. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly TNF-α, are known to induce insulin resistance by interfering with the insulin receptor signaling pathway in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue.

This impaired insulin sensitivity forces the pancreas to produce more insulin, leading to hyperinsulinemia. In men, hyperinsulinemia can further suppress testosterone production. In women, it is a key pathological feature of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), driving excess androgen production by the ovaries.

This inflammatory and insulin-resistant state also dysregulates cellular nutrient-sensing pathways. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, critical for muscle protein synthesis and cell growth, is inhibited by both alcohol and chronic inflammation. Conversely, the AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) pathway, which signals energy deficit and promotes catabolism, is often activated. This creates a cellular environment that favors muscle breakdown and fat storage, directly opposing the anabolic signals of hormones like testosterone and growth hormone.

Advanced Interventions and Clinical Context

This systems-level understanding informs a more sophisticated therapeutic approach. While hormonal optimization protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy (e.g. Sermorelin, Ipamorelin), are effective tools for restoring physiological hormone levels, their success can be limited in the face of unaddressed systemic inflammation.

A patient on TRT who continues to engage in chronic alcohol consumption without addressing the underlying gut dysbiosis will experience suboptimal results. The persistent inflammation will continue to suppress endogenous function and the increased aromatase activity, fueled by inflammation and adipose tissue, will shunt the administered testosterone toward estrogen, requiring higher doses of aromatase inhibitors like Anastrozole and increasing the potential for side effects.

A truly personalized and effective protocol must therefore integrate these powerful clinical tools with foundational strategies aimed at healing the gut and quenching inflammation. This creates a synergistic effect where the restored hormonal milieu can function optimally in a low-inflammatory environment.

- Targeted Nutritional Compounds ∞ Beyond basic nutrient repletion, specific bioactive compounds can be used to modulate these pathways. Curcumin, the active compound in turmeric, is a potent inhibitor of NF-κB, the master transcription factor for inflammatory cytokines. Omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) provide the precursors for specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), which actively resolve inflammation. Resveratrol has been shown to activate SIRT1, a longevity gene that improves mitochondrial function and insulin sensitivity.

- Microbiome Modulation ∞ The use of specific probiotic strains (e.g. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG ) and prebiotic fibers (e.g. inulin, fructooligosaccharides) can help restore a healthy microbial balance, reduce LPS load, and enhance the production of beneficial SCFAs like butyrate, which strengthens the gut barrier.

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) ∞ In severe cases of alcohol-related dysbiosis, FMT is emerging as a powerful, albeit still experimental, intervention to completely reset the gut microbiome, with studies showing potential for reducing cravings and improving liver health.

By viewing alcohol’s hormonal impact through the lens of the gut-liver-brain axis, we move toward a more comprehensive and effective treatment paradigm. The goal becomes a restoration of systemic homeostasis. This involves not just replacing deficient hormones but rebuilding the integrity of the body’s foundational barriers and extinguishing the inflammatory fire that originates in the gut. This integrated approach represents the future of personalized endocrine and metabolic medicine.

References

- Van Heertum, Kristin, and B.A. DeRuisseau. “Pathophysiology of the Effects of Alcohol Abuse on the Endocrine System.” Alcohol Research ∞ Current Reviews, vol. 38, no. 2, 2017, pp. 199-217.

- Emanuele, Mary Ann, and Nicholas V. Emanuele. “Alcohol’s Effects on Male Reproduction.” Alcohol Health & Research World, vol. 25, no. 4, 2001, pp. 282-287.

- Rachdaoui, N. and D. K. Sarkar. “Effects of alcohol on the endocrine system.” Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, vol. 46, no. 3, 2017, pp. 535-551.

- Sarkar, D. et al. “Alcohol and the Endocrine System.” Alcohol Research ∞ Current Reviews, vol. 38, no. 2, 2017, pp. 153-155.

- Leclercq, S. et al. “Gut Microbiota and Alcohol-Related Liver Disease ∞ A New Target for an Old Disease.” Journal of Hepatology, vol. 62, no. 1, 2015, pp. S52-S61.

- Frias, J. et al. “Effects of acute alcohol intoxication on pituitary-gonadal axis hormones, pituitary-adrenal axis hormones, β-endorphin and prolactin in human adults of both sexes.” Alcohol and Alcoholism, vol. 37, no. 2, 2002, pp. 169-73.

- Purohit, V. “Can alcohol promote aromatization of androgens to estrogens? A review.” Alcohol, vol. 22, no. 3, 2000, pp. 123-7.

- Engen, P. A. et al. “The gastrointestinal microbiome ∞ alcohol effects on the composition of intestinal microbiota.” Alcohol Research ∞ Current Reviews, vol. 37, no. 2, 2015, pp. 223-36.

- D’Amico, F. et al. “Gut microbiota and alcohol use disorder ∞ A literature review.” World Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 28, no. 46, 2022, pp. 6473-6484.

- Jensen, T. K. et al. “Does moderate alcohol consumption affect fertility? Follow up study among couples planning first pregnancy.” BMJ, vol. 317, no. 7157, 1998, pp. 505-10.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a detailed map of the biological terrain where alcohol and your hormones interact. It translates the abstract feelings of being “off” into a concrete understanding of cellular and systemic processes. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It shifts the focus from a position of passive consequence to one of empowered, proactive engagement with your own physiology. The question now becomes a personal one. How does this map inform the path you choose to walk?

Your body is in constant communication with you through the language of symptoms. The fatigue, the mood shifts, the changes in physical performance ∞ these are all signals. With this new understanding, you can begin to interpret this language with greater clarity.

You can see these signals not as failings, but as invitations to provide targeted support where it is needed most. The journey to optimal health is a continuous dialogue with your own biology. Consider what your next conversation will be. What is the first, smallest step you can take to support your body’s innate drive toward balance and vitality? The power to influence your health is, and always has been, within your grasp.