Fundamentals

You have arrived here carrying a profound and personal question. It is the quiet inquiry that surfaces after months, or perhaps years, of feeling that your own biology is no longer functioning with the vitality it once did.

You have followed the protocols, you have been diligent in your pursuit of wellness, and yet, the results feel incomplete, as if a crucial piece of the conversation between you and your body has been lost.

This experience of dissonance, of a system that seems resistant to conventional solutions, is a valid and deeply human starting point for a more sophisticated line of inquiry. The path forward begins with understanding that your body is not a generic machine.

It is a unique, intricate biological system, shaped by a personal history written in your genetic code. The question of how your unique genetic profile might influence the choices you make about peptide therapies is the key to unlocking a new level of precision and reclaiming your functional self.

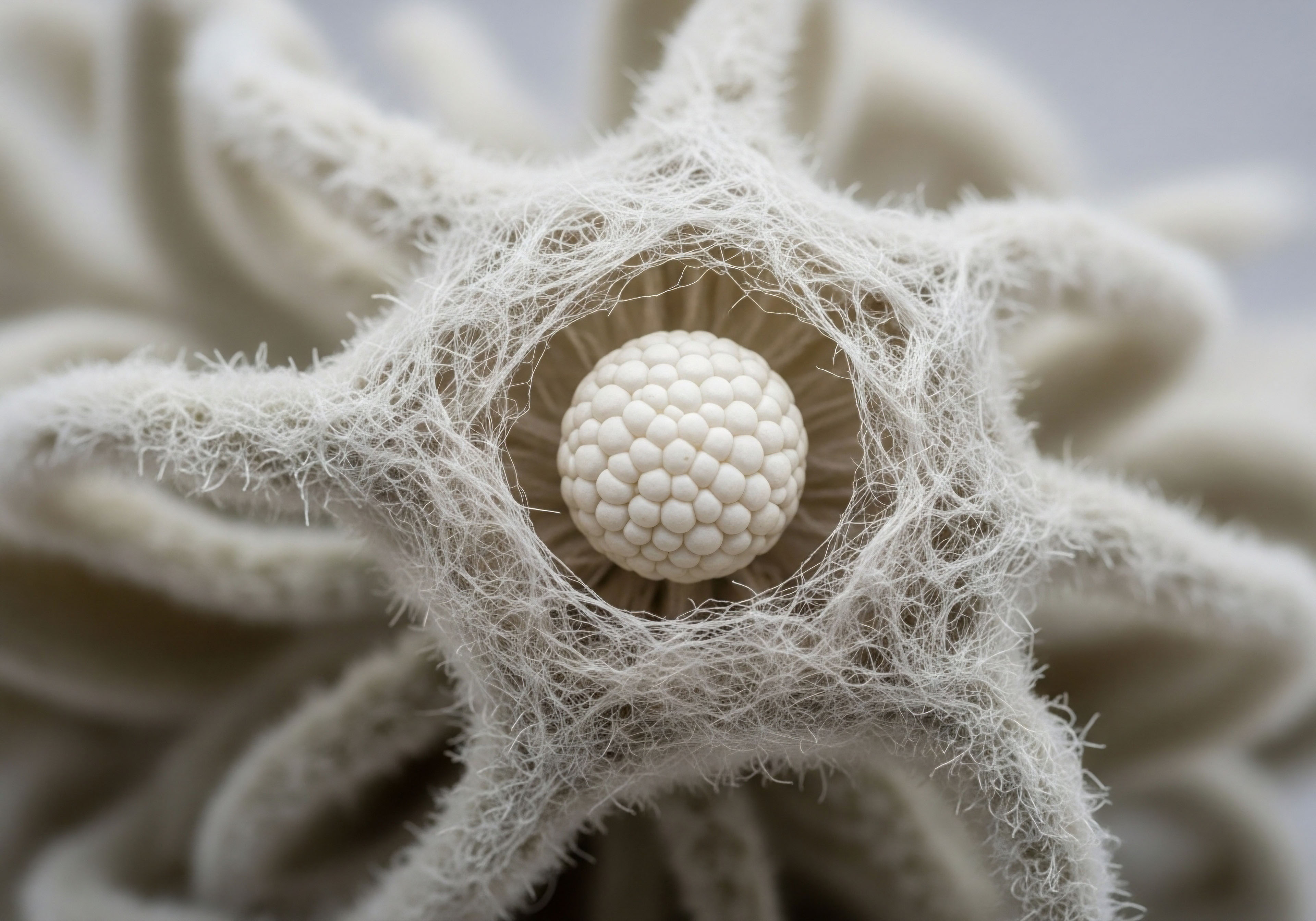

To begin this exploration, we must first appreciate peptides for what they are ∞ molecules of immense specificity. Peptides are short chains of amino acids, the fundamental building blocks of proteins. Within the body’s vast and complex communication network, they act as highly specialized keys, designed to fit equally specialized locks.

These locks are known as receptors, and they are located on the surface of cells throughout your body. When a peptide, such as Sermorelin, which is a growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) analogue, is introduced, it travels through the bloodstream seeking its corresponding receptor.

In the case of Sermorelin, its destination is the GHRH receptor on the pituitary gland. The binding of the peptide to its receptor is the catalytic event; it is the moment a message is delivered and a specific action is initiated. This action, for Sermorelin, is the instruction for the pituitary to synthesize and release your body’s own supply of human growth hormone (hGH). This process is elegant, precise, and foundational to the therapeutic effect of peptides.

Your personal genetic code dictates the precise structure and function of the cellular receptors that receive peptide signals.

The core of our discussion rests upon a simple biological truth ∞ your DNA is the architectural blueprint for every single one of these protein-based receptors. The genes within your cells contain the instructions for building these intricate structures. This is where the concept of personalization becomes critically important.

Minor variations within these genes, known as polymorphisms, can lead to subtle or significant changes in the final structure of the receptor. Imagine a custom-made lock. A slight alteration in its internal tumblers, dictated by a unique design, could mean that a standard key fits perfectly, fits loosely, or perhaps does not fit at all.

In the same way, a genetic variation in your GHRH receptor gene might alter the shape of the receptor itself. This could influence how effectively Sermorelin can bind to it, directly impacting the downstream signal to produce growth hormone. One person’s receptors might welcome the peptide with high affinity, leading to a robust response.

Another individual, due to a different genetic variant, might have receptors that bind less effectively, resulting in a diminished or suboptimal clinical outcome from the very same dose.

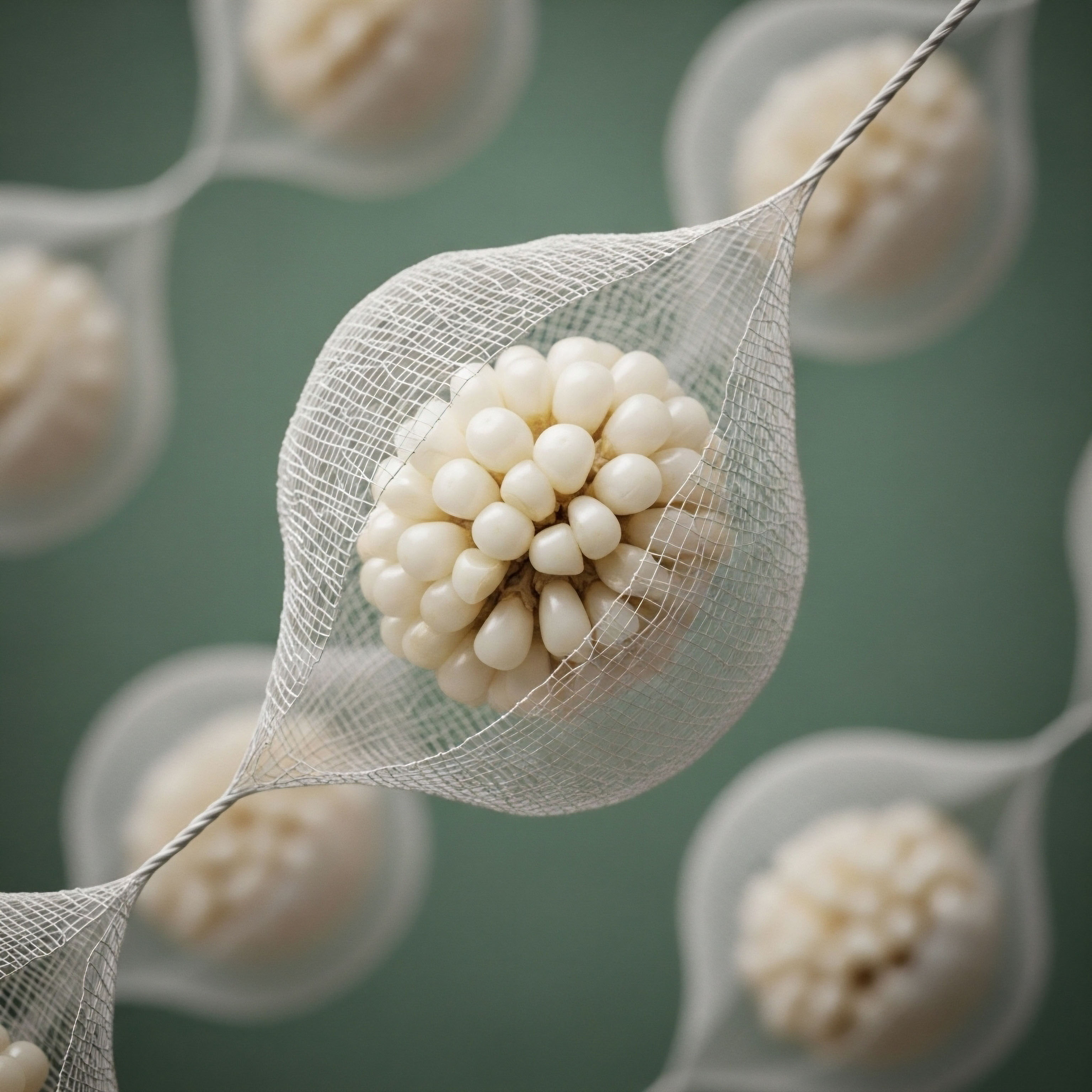

This genetic influence extends beyond the initial signal reception. The body must also metabolize and clear these therapeutic peptides, as well as any other supportive medications in a given protocol, such as Anastrozole in hormone optimization therapies. This metabolic process is largely governed by a family of enzymes in the liver known as the Cytochrome P450 (CYP) system.

These enzymes are the body’s primary mechanism for breaking down a vast array of substances. Just like receptors, these enzymes are proteins built from genetic instructions. Genetic polymorphisms in the CYP genes are common and well-documented, leading to significant differences in how individuals process medications.

One person may be a “rapid metabolizer,” clearing a substance so quickly that it has little time to exert its effect. Another may be a “poor metabolizer,” breaking it down so slowly that it builds up in the system, increasing the risk of side effects.

Understanding your specific genetic profile for these key enzymes provides a second layer of profound insight, allowing for a therapeutic strategy that anticipates how your body will not only receive a signal but also process the messenger.

Intermediate

As we move deeper into the clinical application of this knowledge, we can begin to connect the foundational concepts of genetic variability to the specific hormonal optimization protocols you may be considering or currently undergoing. The goal is to translate abstract genetic data into concrete, actionable insights that refine and personalize your therapeutic journey.

We will examine how pharmacogenomics, the study of how genes affect a person’s response to drugs, directly informs the selection and management of peptide therapies and their supporting components. This is where the science of individuality meets the practice of clinical medicine, creating a far more sophisticated and responsive approach to wellness.

Genetic Influence on Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy

Growth hormone peptide therapies, such as those using Sermorelin, Ipamorelin, or CJC-1295, are designed to stimulate the pituitary gland’s endogenous production of hGH. Their effectiveness is predicated on a functional Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Somatotropic axis. The success of this intervention is heavily dependent on the integrity of the signaling pathway, from the receptor that receives the peptide’s message to the cellular machinery that responds. Genetic variations can introduce inefficiencies at multiple points along this cascade.

The GHRHR Gene and Sermorelin Efficacy

The primary target for Sermorelin is the Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone Receptor (GHRHR). It is the lock for Sermorelin’s key. Genetic variations, or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), within the GHRHR gene are of paramount importance. Research has identified specific variants that can alter the receptor’s structure and function.

For instance, a particular SNP might result in an amino acid substitution that changes the three-dimensional shape of the receptor’s binding site. This can decrease the binding affinity of Sermorelin, meaning the peptide does not “dock” as securely as it should.

The clinical consequence is a blunted signal to the pituitary, leading to a less robust release of growth hormone and a diminished therapeutic effect. An individual with such a variant might report feeling minimal benefits from a standard Sermorelin protocol, not because the therapy is ineffective in principle, but because it is mismatched to their specific genetic hardware.

Downstream Signaling and the GH1 Gene

Effective receptor binding is only the first step. The pituitary must then synthesize and release growth hormone. The primary gene responsible for encoding human growth hormone is the GH1 gene. Variations in this gene can impact the baseline production of GH.

Even with a perfectly functioning GHRH receptor and a strong signal from Sermorelin, an underlying genetic tendency towards lower GH synthesis could limit the ultimate response. This creates a scenario where the “message” is received loud and clear, but the “factory” has a lower production capacity.

Understanding this allows for a more realistic expectation of outcomes and may guide the clinician toward combination therapies, perhaps using a GHS-R pathway agonist like Ipamorelin to provide a different kind of stimulatory signal.

Genetic variations in metabolic enzymes determine the speed at which your body processes and clears both peptides and ancillary medications.

Pharmacogenomics of Ancillary Medications in Hormone Protocols

Many therapeutic protocols involve more than just a single peptide. In Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), for instance, men are often prescribed Anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, to control the conversion of testosterone to estrogen. The metabolism of Anastrozole is handled by the Cytochrome P450 enzyme system, presenting another critical point of genetic influence.

CYP Enzymes and Anastrozole Metabolism

The enzymes from the CYP2C and CYP3A families are heavily involved in breaking down Anastrozole. Genetic polymorphisms in these enzymes can lead to clinically significant differences in drug clearance. The table below illustrates how different metabolic phenotypes, dictated by genetics, can affect Anastrozole levels and, consequently, patient outcomes.

| Metabolizer Phenotype | Genetic Profile Example | Impact on Anastrozole Metabolism | Clinical Implications in a TRT Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrarapid Metabolizer | Increased enzyme activity (e.g. certain CYP2C19 variants) | Anastrozole is cleared from the body very quickly. | The standard dose may be insufficient to control estrogen levels, leading to estrogenic side effects like water retention or gynecomastia despite adherence to the protocol. A higher dose or more frequent administration might be necessary. |

| Extensive (Normal) Metabolizer | Standard enzyme activity. | Anastrozole is cleared at a typical rate. | The patient is likely to respond as expected to standard dosing protocols. |

| Intermediate Metabolizer | Reduced enzyme activity. | Anastrozole is cleared more slowly than normal. | A standard dose may be slightly too high, potentially leading to excessive estrogen suppression. This can cause symptoms like joint pain, low libido, or negative mood changes. |

| Poor Metabolizer | Significantly reduced or absent enzyme activity (e.g. certain CYP2C19 or CYP2D6 variants). | Anastrozole is cleared very slowly, leading to its accumulation. | A standard dose can lead to a significant buildup of the drug, causing severe estrogen suppression and associated side effects. A substantially lower dose is required to achieve the desired therapeutic window. |

Synthesizing Genetic Data for Personalized Protocols

A personalized genetic profile provides a roadmap. It allows a clinician to move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach and proactively adjust a protocol based on an individual’s unique biological landscape. This proactive personalization can improve efficacy, enhance safety, and validate the patient’s experience. If a patient reports suboptimal results or unusual side effects, genetic data can provide a clear, biological explanation. This transforms the conversation from one of trial and error to one of data-driven precision.

- Peptide Selection ∞ If a patient has a known polymorphism that reduces GHRHR sensitivity, a clinician might choose a peptide that works through a different mechanism, like Ipamorelin (a ghrelin mimetic), or use a combination approach to stimulate the pituitary through multiple pathways.

- Dosing Adjustments ∞ Knowledge of a patient’s CYP450 enzyme status can guide the initial dosing of ancillary medications like Anastrozole, potentially avoiding weeks or months of adjustments and uncomfortable side effects. A known “poor metabolizer” would be started on a much more conservative dose from day one.

- Managing Expectations ∞ Genetic data helps set realistic expectations. A patient with variants affecting both receptor sensitivity and baseline hormone production can be counseled that their journey to optimization may require more fine-tuning and that progress will be measured against their own unique baseline.

Academic

An academic exploration of this topic requires a granular analysis of the molecular mechanisms that connect genotype to clinical phenotype. We must move from the conceptual to the specific, examining the precise genetic loci, enzymatic pathways, and systems-level interactions that govern an individual’s response to peptide-based interventions.

The central thesis is that a comprehensive pharmacogenomic profile is an indispensable tool for optimizing peptide delivery, mitigating adverse events, and advancing the practice of personalized endocrinology. This discussion will focus on the quantifiable impact of genetic polymorphisms on peptide pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, grounded in molecular biology and clinical research.

Molecular Heterogeneity of the GHRH/GH Axis

The efficacy of growth hormone secretagogues like Sermorelin is fundamentally dependent on the molecular integrity of the GHRH/GH signaling axis. Genetic variation introduces a significant degree of heterogeneity into this system, which can be dissected at several key points.

Functional Consequences of GHRHR Polymorphisms

The gene encoding the Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone Receptor (GHRHR) is located on chromosome 7. Numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified within this gene, some of which have demonstrable functional consequences. For example, a missense mutation can result in the substitution of one amino acid for another in a critical domain of the receptor protein.

If this substitution occurs within the N-terminal extracellular domain, which is responsible for binding GHRH and its analogues, it can alter the electrostatic and steric properties of the binding pocket. This can reduce the binding affinity (Kd) of Sermorelin for the receptor.

A lower binding affinity means that a higher concentration of the peptide is required to achieve the same level of receptor occupancy and subsequent activation of the intracellular signaling cascade, which involves Gs protein activation and adenylyl cyclase-mediated production of cyclic AMP (cAMP). Individuals heterozygous or homozygous for such a variant may be classified as “low responders” to standard Sermorelin dosages, a clinical observation that is directly explained by this molecular mismatch.

What Are the Genetic Implications for Post-Receptor Signaling?

Beyond the receptor itself, the intracellular signaling pathway is also subject to genetic variation. The activation of the GHRHR initiates a cascade involving G-proteins, adenylyl cyclase, and protein kinase A (PKA). Genes encoding any of these downstream effector proteins can harbor polymorphisms that modulate signal strength.

For instance, a variant in a G-protein subunit could impair its ability to dissociate and activate adenylyl cyclase efficiently, dampening the entire downstream response. Furthermore, the expression and activity of phosphodiesterases (PDEs), the enzymes that degrade cAMP and terminate the signal, are also genetically determined.

A patient with a hyper-functional PDE variant might experience a more rapid termination of the intracellular signal, shortening the duration of GH release in response to a pulse of Sermorelin. This complex interplay of multiple genetic factors highlights the need for a systems-biology approach, analyzing the entire pathway rather than a single gene in isolation.

The Cytochrome P450 Superfamily and Its Role in Hormonal Homeostasis

The metabolism of xenobiotics, including therapeutic peptides and ancillary drugs, is a critical determinant of their net effect. The Cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily of enzymes is central to this process, and its genetic diversity is a primary driver of interindividual variability in drug response.

Impact of CYP Polymorphisms on Therapeutic Protocols

While peptides themselves are often cleared by proteolysis, the small-molecule drugs frequently used in conjunction with them are heavily reliant on CYP-mediated metabolism. Anastrozole, a key component in many TRT protocols, is metabolized by multiple CYP enzymes, including CYP3A4, CYP2C19, and CYP1A2. The genes for these enzymes are highly polymorphic. Let us consider the clinical implications in detail.

The CYP2C19 gene, for example, has several well-characterized non-functional alleles (e.g. 2, 3). Individuals who are homozygous for these alleles are “poor metabolizers” (PMs) and exhibit significantly impaired clearance of CYP2C19 substrates. When a PM patient is prescribed a standard dose of Anastrozole, the drug’s concentration can accumulate to levels far exceeding the therapeutic target.

This leads to excessive aromatase inhibition and a precipitous drop in estradiol levels, inducing symptoms such as severe joint pain, cognitive fog, and diminished libido. Conversely, individuals with the CYP2C19 17 allele are “ultrarapid metabolizers” (UMs) and clear the drug very quickly.

In these patients, a standard dose may be completely ineffective at controlling aromatization, leaving them vulnerable to hyperestrogenic side effects. A pharmacogenomic test can identify these phenotypes prospectively, allowing for the selection of a dramatically different starting dose tailored to the patient’s metabolic capacity.

The following table provides a detailed overview of key genetic variants and their documented impact on peptide and hormone-related therapies.

| Gene Locus | Specific Variant (Allele) | Molecular Effect | Clinical Relevance to Peptide/Hormone Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| GHRHR | Various missense SNPs | Alters the 3D structure of the GHRH receptor, potentially reducing binding affinity for Sermorelin/GHRH analogues. | Reduced GH pulse amplitude in response to therapy. Patient may require higher doses or alternative secretagogues (e.g. ghrelin mimetics). |

| GH1 | Promoter region variants | Affects the basal transcription rate of the growth hormone gene. | Determines the pituitary’s inherent capacity for GH synthesis, setting the ceiling for the maximal response to any secretagogue. |

| CYP2D6 | 3, 4, 5 (non-functional alleles) | Absence of functional enzyme; “Poor Metabolizer” phenotype. | Significantly impacts metabolism of Tamoxifen (used in some PCT protocols) to its active metabolite, endoxifen, rendering the drug ineffective. Also affects metabolism of some antidepressants and beta-blockers. |

| CYP2C19 | 2, 3 (non-functional alleles) | Absence of functional enzyme; “Poor Metabolizer” phenotype for drugs like Clomid and some proton pump inhibitors. | Reduced efficacy of Clomiphene in post-TRT protocols. Significantly slowed metabolism of Anastrozole, requiring drastic dose reduction. |

| CYP2C19 | 17 (gain-of-function allele) | Increased enzyme transcription; “Ultrarapid Metabolizer” phenotype. | Accelerated metabolism of Anastrozole, often requiring higher doses to achieve therapeutic effect in TRT. |

| CYP3A4/5 | Various SNPs (e.g. CYP3A4 22, CYP3A5 3) | Variable enzyme activity affecting a wide range of drugs. CYP3A5 3 is a non-functional allele common in Caucasians. | Alters clearance rates for testosterone, as well as numerous other medications, influencing overall drug exposure and potential for interactions. Critical for dosing Tacrolimus. |

This data-driven approach transforms treatment from a reactive process of trial-and-error to a proactive strategy based on an individual’s unique genetic makeup. It provides a mechanistic explanation for observed clinical variability and empowers the clinician to make more informed, personalized decisions from the outset of therapy. The future of effective peptide and hormone optimization lies in the integration of such comprehensive pharmacogenomic analyses into standard clinical practice.

References

- Mayo, K. E. et al. “Regulation of the pituitary somatotroph cell by GHRH and its receptor.” Recent Progress in Hormone Research, vol. 50, 1995, pp. 35-73.

- Zanger, U. M. and M. Schwab. “Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism ∞ regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation.” Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 138, no. 1, 2013, pp. 103-41.

- Ingelman-Sundberg, M. et al. “Polymorphic Cytochrome P450 Enzymes (CYPs) and Their Role in Personalized Therapy.” Journal of Personalized Medicine, vol. 3, no. 4, 2013, pp. 286-303.

- Walker, R. F. et al. “Effects of aging on the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-I axis.” Endocrine, vol. 2, no. 4, 1994, pp. 333-339.

- Veldhuis, J. D. et al. “Differential impacts of age, body mass index, and serum insulin-like growth factor-I on the dose-responsiveness of growth hormone (GH) secretion to GH-releasing hormone and GH-releasing peptide-2 in healthy men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 84, no. 5, 1999, pp. 1657-65.

- Di Somma, C. et al. “The use of growth hormone-releasing hormone in adult growth hormone deficiency.” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 33, no. 8, 2010, pp. 586-91.

- Corpas, E. et al. “Human growth hormone and human growth hormone-releasing hormone (1-29)-NH2 in the treatment of elderly men with idiopathic growth hormone deficiency.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 75, no. 1, 1992, pp. 168-74.

- Dehkhoda, F. et al. “The Role of Cytochrome P450 Metabolism in Antineoplastic Drug Interactions.” Cancers, vol. 12, no. 9, 2020, p. 2487.

- Almazroo, O. A. et al. “Drug-Drug Interactions with Antiepileptic Drugs ∞ A Focus on Cytochrome P450 Enzymes.” Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, vol. 13, no. 4, 2017, pp. 419-432.

- Prakash, A. and K. L. Goa. “Sermorelin ∞ a review of its use in the diagnosis and treatment of children with idiopathic growth hormone deficiency.” BioDrugs, vol. 12, 1999, pp. 139-56.

Reflection

The information you have absorbed represents more than a collection of scientific facts. It is a new lens through which to view your own body and its intricate inner workings. The path to reclaiming your vitality is not about finding a single, universal answer. It is about learning to ask more precise questions.

Your biology has a unique dialect, a language encoded in your genes. The feeling of being unheard by conventional protocols may simply be a sign that the conversation has been happening in the wrong language. By beginning to understand your personal genetic blueprint, you are learning to translate.

You are equipping yourself to engage in a more productive, collaborative dialogue with your own physiology and with the clinicians who guide you. This knowledge is the first, most essential step. The journey forward is one of continued discovery, where each piece of personal data illuminates the next step on a path that is yours and yours alone.