Fundamentals

The feeling of anxiety that coincides with hormonal support protocols is a deeply personal and often unsettling experience. It can manifest as a persistent, low-level hum of unease or as acute waves of panic that seem to arise without a clear trigger.

This experience is not a matter of willpower; it is a direct reflection of profound biological shifts occurring within your body. Understanding this connection is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of calm and control.

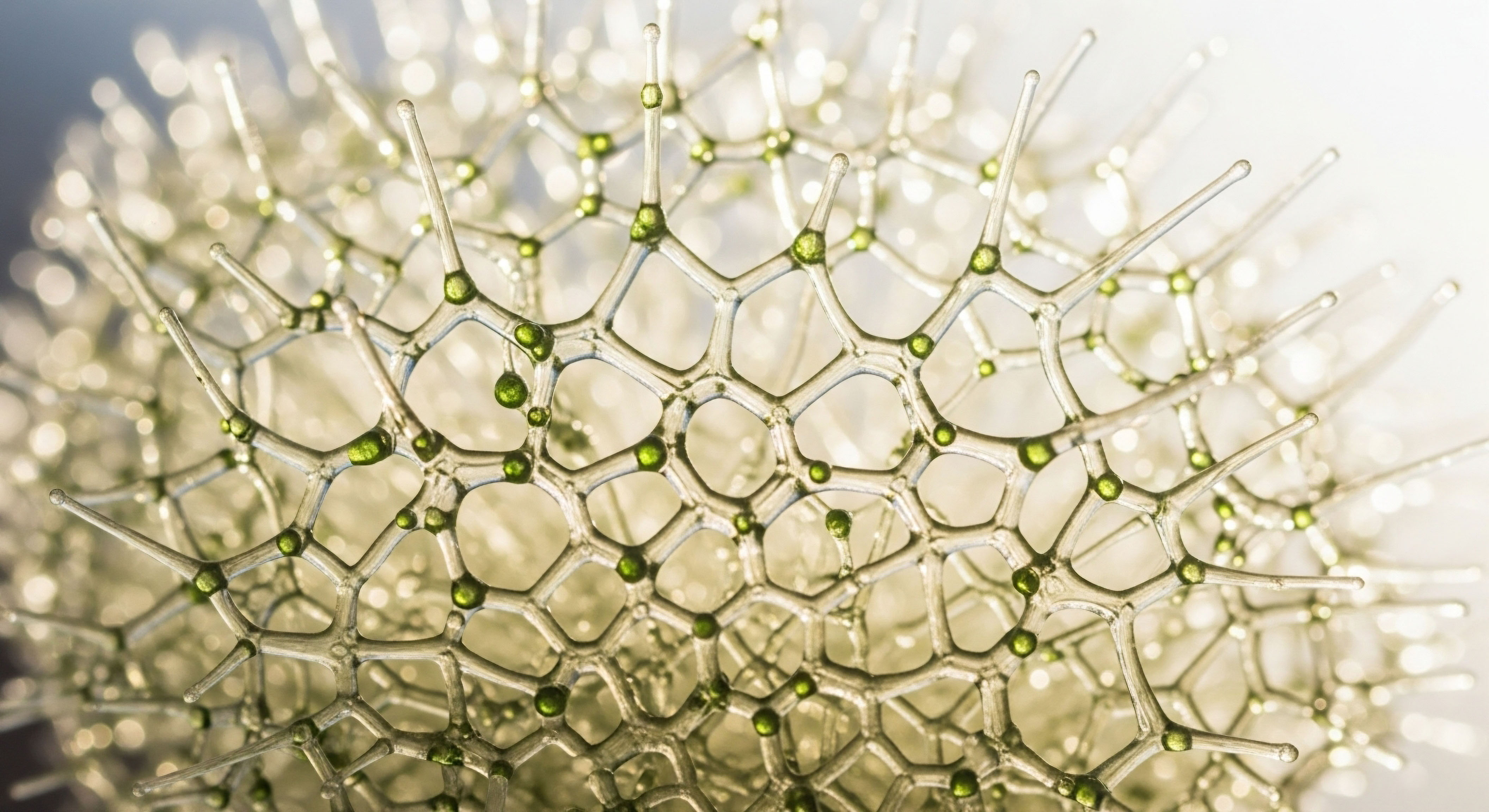

Your body’s endocrine system is an intricate communication network, using hormones as chemical messengers to regulate everything from your metabolism and energy levels to your mood and cognitive function. When you begin a protocol like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or peptide therapy, you are intentionally adjusting this complex system to restore balance and vitality.

These adjustments, while beneficial, can temporarily alter the delicate interplay between hormones and neurotransmitters ∞ the chemicals responsible for mood regulation in your brain. Hormones such as testosterone, estrogen, and cortisol share biochemical pathways with neurotransmitters like serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

Serotonin is often associated with feelings of well-being and happiness, while GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, responsible for producing a calming effect. The raw materials needed to produce these essential chemicals, such as amino acids, vitamins, and minerals, are derived entirely from your diet. Therefore, the food you consume directly influences the available resources for both hormonal and neurological stability.

A personalized dietary strategy provides the specific biochemical tools your body requires to adapt to hormonal changes, thereby stabilizing mood.

Think of your endocrine and nervous systems as a finely tuned orchestra. For the orchestra to produce a harmonious sound, each musician needs a well-maintained instrument. In this analogy, your diet provides the materials ∞ the wood, the strings, the brass ∞ to build and repair those instruments.

If the supply of high-quality materials is insufficient or inconsistent, some instruments will fall out of tune, creating dissonance. This dissonance can manifest as anxiety. A strategic dietary approach ensures a steady supply of the precise nutrients needed to keep the entire orchestra in sync, allowing your body to adapt to therapeutic hormonal changes with greater ease and stability.

The Neuroendocrine Connection to Mood

The link between your hormones and your mood is seated in the deep, interconnected wiring of your body. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the central command system for your stress response. When you experience stress, the HPA axis activates, culminating in the release of cortisol.

While essential for short-term survival, chronically elevated cortisol can disrupt the production of other hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, and interfere with the function of mood-regulating neurotransmitters. Hormonal support protocols aim to rebalance these systems, but the adjustment period itself can be a stressor that activates the HPA axis.

Personalized dietary adjustments can directly support the HPA axis and mitigate this response. For instance, ensuring a consistent intake of complex carbohydrates can help stabilize blood sugar levels. Wild fluctuations in blood sugar are a significant physiological stressor that can trigger cortisol release.

By maintaining stable glucose levels, you reduce the burden on your adrenal glands and create a more stable internal environment for your hormonal recalibration to take place. This nutritional stability provides a foundation upon which hormonal therapies can work most effectively, minimizing the potential for anxiety as a side effect.

Building Blocks for a Calm Mind

Your brain’s ability to generate feelings of calm and focus is dependent on a constant supply of specific nutritional building blocks. Neurotransmitters are not created from thin air; they are synthesized from amino acids found in the protein you eat.

Tryptophan is the precursor to serotonin, while tyrosine is the precursor for dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to motivation and focus. The conversion of these amino acids into active neurotransmitters requires the presence of specific vitamins and minerals, which act as cofactors in the biochemical reactions.

For example, Vitamin B6 is a critical cofactor in the synthesis of both serotonin and GABA. Magnesium plays a vital role in regulating the activity of the nervous system and has been shown to have a calming effect. Zinc is another essential mineral that influences how your brain responds to stress.

When you are undergoing endocrine support, your body’s demand for these micronutrients may increase as it works to build new hormonal and neurological pathways. A diet rich in lean proteins, leafy green vegetables, nuts, and seeds provides a robust supply of these essential components, directly fueling the neurochemical processes that underpin a stable and resilient mood.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational concepts, we can examine the specific biochemical mechanisms through which personalized nutrition directly modulates the anxiety that can accompany endocrine support. When a patient begins a protocol, whether it is weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate for a male with andropause or low-dose testosterone with progesterone for a woman in perimenopause, the body must adapt to new signaling molecules.

This adaptation requires significant metabolic resources. A targeted dietary strategy supplies these resources, functioning as a critical support system that enhances the efficacy of the therapy while buffering against neurochemical instability.

The relationship between blood sugar regulation and anxiety is a prime example. Hormonal therapies can influence insulin sensitivity. The introduction of therapeutic testosterone, for instance, can improve insulin sensitivity over the long term, but the initial adjustment period may involve fluctuations.

A diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugars leads to sharp spikes and subsequent crashes in blood glucose. These crashes trigger a counter-regulatory hormonal response, including the release of cortisol and adrenaline from the adrenal glands, to bring glucose levels back to normal.

This physiological alarm state is subjectively experienced as anxiety, complete with heart palpitations, nervousness, and a sense of dread. A dietary plan focused on low-glycemic-load foods ∞ such as fibrous vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats ∞ prevents these dramatic swings, thereby reducing the burden on the HPA axis and promoting a calmer internal state.

How Do Dietary Strategies Influence Hormonal Pathways?

Different dietary frameworks can be strategically employed to support specific goals during endocrine therapy. The choice of strategy depends on the individual’s unique physiology, lab markers, and the specific hormonal protocol being implemented. The objective is to create an internal environment that is anti-inflammatory, metabolically flexible, and rich in the specific nutrients needed for hormone and neurotransmitter synthesis.

For example, a Mediterranean-style diet, rich in omega-3 fatty acids from fatty fish, monounsaturated fats from olive oil, and a wide array of polyphenols from colorful plants, provides powerful anti-inflammatory benefits. Systemic inflammation can disrupt hormone receptor sensitivity and interfere with the production of neurotransmitters.

By reducing inflammation, this dietary pattern helps ensure that the therapeutic hormones can effectively bind to their target receptors and exert their intended effects. It also provides the essential fatty acids that are structural components of brain cells, supporting overall neurological health.

Strategic dietary choices directly manage the inflammatory and metabolic cascades that can otherwise translate hormonal adjustments into anxiety.

The following table compares several dietary strategies and their specific mechanisms of action relevant to mitigating anxiety during endocrine support:

| Dietary Strategy | Primary Mechanism | Impact on Hormonal/Neurochemical Pathways | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Glycemic Load | Blood sugar stabilization |

Reduces cortisol and adrenaline spikes from reactive hypoglycemia. Improves insulin sensitivity, which can be affected by TRT. This creates a more stable HPA axis environment. |

Individuals experiencing energy crashes, irritability, or anxiety between meals. |

| Mediterranean Diet | Anti-inflammatory |

High intake of omega-3s and polyphenols reduces systemic inflammation, improving hormone receptor sensitivity. Supports cardiovascular health, which is synergistic with many hormonal protocols. |

General wellness and long-term health support during any endocrine therapy. |

| Ketogenic/Low-Carb | Enhanced GABAergic tone |

Ketone bodies, particularly beta-hydroxybutyrate, have been shown to increase the synthesis of the calming neurotransmitter GABA. This can have a direct anxiolytic effect. |

Specific cases where anxiety is severe and potentially linked to glutamate excitotoxicity; requires careful clinical supervision. |

| Nutrient-Dense Ancestral | Micronutrient repletion |

Focuses on high-bioavailability sources of zinc, magnesium, B vitamins, and iron from whole foods like organ meats, shellfish, and root vegetables. These are critical cofactors for neurotransmitter synthesis. |

Patients with known or suspected micronutrient deficiencies that could be exacerbating mood symptoms. |

The Critical Role of Micronutrient Cofactors

The biochemical pathways that convert amino acids into mood-regulating neurotransmitters are entirely dependent on specific vitamin and mineral cofactors. Without an adequate supply of these micronutrients, the conversion process can become sluggish or impaired, leading to a relative deficiency of key chemicals like serotonin and dopamine, even if protein intake is sufficient. Endocrine support protocols can increase the metabolic demand for these cofactors, making dietary intake even more critical.

Consider the synthesis of serotonin from the amino acid tryptophan. This multi-step process requires iron, vitamin B6, and magnesium to proceed efficiently. Similarly, the conversion of tyrosine to dopamine requires iron and vitamin B6. A diet lacking in these key nutrients can create a bottleneck in neurotransmitter production, contributing to feelings of anxiety, depression, or low motivation.

This is particularly relevant for patients on protocols that include medications like Anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor used to control estrogen in men on TRT. While necessary for managing potential side effects, the adjustment of the estrogen-to-testosterone ratio is a significant metabolic event that benefits from robust nutritional support.

Here is a list of key micronutrients and their roles in mitigating anxiety:

- Magnesium ∞ Acts as a natural calcium channel blocker at the NMDA receptor, which helps to calm the nervous system and prevent excessive neuronal firing. It also enhances the sensitivity of GABA receptors. Food sources include leafy greens, almonds, pumpkin seeds, and dark chocolate.

- Zinc ∞ Plays a crucial role in modulating the brain’s response to stress. It is involved in the synthesis of both serotonin and GABA and helps to regulate cortisol levels. Oysters, beef, and pumpkin seeds are excellent sources.

- Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) ∞ A vital cofactor for the enzymes that convert tryptophan to serotonin and glutamate to GABA. A deficiency can directly impair the production of these calming neurotransmitters. Found in chickpeas, liver, tuna, and salmon.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids (EPA & DHA) ∞ These fats are integral components of neuronal cell membranes, influencing receptor function and signal transmission. They also have potent anti-inflammatory effects that protect neurological tissue. Abundant in fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, and sardines.

By consciously constructing a diet rich in these specific nutrients, an individual can provide their body with the necessary tools to navigate the complexities of hormonal recalibration, transforming a potentially anxious experience into a smooth and effective journey toward renewed health.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of dietary influence on anxiety during endocrine support requires a systems-biology perspective, focusing on the intricate communication network of the gut-brain-hormone axis. This tripartite system represents a complex, bidirectional feedback loop where the metabolic activity of the gut microbiome directly influences both central nervous system function and peripheral endocrine signaling.

Anxiety, in this context, can be viewed as a systemic distress signal arising from dysregulation within this axis, often exacerbated by the profound physiological shifts initiated by hormonal therapies like TRT or peptide treatments such as Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295.

The gut microbiota, a complex ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms, is a primary mediator in this axis. These microbes are not passive residents; they are active metabolic factories that produce a vast array of neuroactive compounds. They synthesize neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, and they produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, propionate, and acetate through the fermentation of dietary fiber.

Butyrate, for example, serves as a primary energy source for colonocytes, enhances the integrity of the intestinal barrier, and functions as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, which can modulate gene expression in the brain, including genes related to neuroplasticity and stress resilience.

A diet low in fiber and high in processed foods can lead to gut dysbiosis ∞ an imbalance in the microbial community. This state is often characterized by a reduction in beneficial SCFA-producing bacteria and an overgrowth of pathobionts.

Dysbiosis can lead to increased intestinal permeability, often termed “leaky gut.” This allows bacterial components like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to translocate from the gut into systemic circulation, triggering a low-grade, chronic inflammatory response. This systemic inflammation is a potent disruptor of both the HPA axis and steroidogenesis (the production of hormones), creating a physiological backdrop that is highly conducive to anxiety.

What Is the Tryptophan Steal Phenomenon?

The amino acid tryptophan presents a critical junction in the gut-brain-hormone axis. Tryptophan is the essential precursor for the synthesis of serotonin. However, it is also the precursor for the kynurenine pathway, which is activated by inflammatory cytokines. During states of systemic inflammation ∞ such as that triggered by gut dysbiosis and LPS translocation ∞ the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is upregulated. IDO shunts available tryptophan away from the serotonin synthesis pathway and down the kynurenine pathway.

This phenomenon, sometimes called the “tryptophan steal,” has profound implications for mood. It simultaneously reduces the brain’s capacity to produce serotonin, the “feel-good” neurotransmitter, while increasing the production of kynurenine pathway metabolites like quinolinic acid. Quinolinic acid is an NMDA receptor agonist, meaning it has an excitatory effect on neurons.

An excess of quinolinic acid can lead to a state of neuronal excitability and neurotoxicity, which manifests as anxiety, agitation, and cognitive dysfunction. Therefore, a personalized dietary plan that focuses on reducing gut-derived inflammation ∞ through high-fiber intake, probiotic and prebiotic foods, and an abundance of anti-inflammatory polyphenols ∞ can help prevent the tryptophan steal, preserving tryptophan for serotonin synthesis and promoting a calmer neurochemical environment.

The competition for tryptophan between serotonin synthesis and the inflammatory kynurenine pathway is a key biochemical battleground where diet determines the outcome for mood.

The following table details the competition for key amino acid precursors and how dietary and hormonal factors influence their ultimate fate.

| Amino Acid Precursor | Anxiolytic Pathway (Desired) | Anxiogenic Pathway (Undesired) | Dietary/Hormonal Influences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan | Conversion to 5-HTP, then Serotonin (promotes calm, well-being). Requires B6, Mg, Zn. |

Conversion to Kynurenine, then Quinolinic Acid (neuroexcitatory). Activated by inflammation (LPS) and high cortisol. |

Diet ∞ High-fiber, polyphenol-rich diet reduces inflammation. Adequate protein provides tryptophan. Hormones ∞ High cortisol from stress shunts tryptophan to kynurenine. |

| Tyrosine | Conversion to L-DOPA, then Dopamine (promotes motivation, focus). Requires B6, Iron. |

Depletion during high-stress states, leading to reduced catecholamine reserves and subsequent fatigue and low mood. |

Diet ∞ High-quality protein ensures adequate tyrosine supply. Hormones ∞ Chronic stress depletes dopamine stores faster than they can be synthesized. |

| Glutamine | Conversion to Glutamate, then GABA (primary inhibitory neurotransmitter). Requires B6, Mg. |

Excessive conversion to Glutamate without sufficient conversion to GABA, leading to excitotoxicity. |

Diet ∞ Adequate B6 and Magnesium are critical for the GAD enzyme that converts glutamate to GABA. Hormones ∞ Hormonal shifts can alter the glutamate/GABA balance. |

Genetic Considerations and Nutritional Personalization

Further personalization of dietary strategies can be informed by an individual’s genetic predispositions. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes that code for key enzymes can influence an individual’s response to stress and their baseline anxiety levels. For example, the enzyme Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is responsible for breaking down catecholamines like dopamine and adrenaline in the prefrontal cortex.

Individuals with a “slow” COMT variant may have higher baseline levels of these neurotransmitters but are also more susceptible to anxiety and burnout under stress because they are slower to clear them.

For a person with a slow COMT variant undergoing a stimulating therapy like TRT, a dietary strategy that supports methylation pathways becomes particularly important. This would involve ensuring an ample supply of methyl donors like folate (from leafy greens), vitamin B12 (from animal products), and choline (from eggs).

Additionally, they might benefit from nutrients like magnesium, which can help to temper the adrenergic response. Conversely, someone with a “fast” COMT variant might experience lower baseline dopamine and could benefit from ensuring adequate intake of the precursor amino acid tyrosine to support dopamine production.

Similarly, variations in the MTHFR gene, which is critical for folate metabolism, can impact the production of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). BH4 is an essential cofactor for the synthesis of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Individuals with MTHFR variants may have a reduced capacity to produce BH4, leading to lower neurotransmitter levels.

For these individuals, a diet rich in pre-formed folate (not synthetic folic acid) and other B vitamins is not just beneficial; it is a clinical necessity to support mood stability, especially when the metabolic demands of the body are increased by endocrine therapies.

References

- Jenkins, T. A. Nguyen, J. C. Polglaze, K. E. & Bertrand, P. P. (2016). Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis. Nutrients, 8(1), 56.

- Clapp, M. Aurora, N. Herrera, L. Bhatia, M. Wilen, E. & Wakefield, S. (2017). Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health ∞ The gut-brain axis. Clinics and Practice, 7(4), 987.

- Boyle, N. B. Lawton, C. & Dye, L. (2017). The Effects of Magnesium Supplementation on Subjective Anxiety and Stress ∞ A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 9(5), 429.

- Parker, G. & Brotchie, H. (2011). Mood effects of the amino acids tryptophan and tyrosine ∞ ‘Food for Thought’ III. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(6), 417 ∞ 426.

- Kennedy, D. O. (2016). B Vitamins and the Brain ∞ Mechanisms, Dose and Efficacy ∞ A Review. Nutrients, 8(2), 68.

- The Endocrine Society. (2022). Clinical Practice Guidelines. Retrieved from Endocrine Society website.

- Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. (2017). The microbiome-gut-brain axis in health and disease. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, 46(1), 77 ∞ 89.

- Sarris, J. Logan, A. C. Akbaraly, T. N. Amminger, G. P. Balanzá-Martínez, V. Freeman, M. P. & Jacka, F. N. (2015). Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(3), 271-274.

- Lach, G. Schellekens, H. Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. (2018). Anxiety, Depression, and the Microbiome ∞ A Role for Gut Peptides. Neurotherapeutics, 15(1), 36-59.

- Foster, J. A. Rinaman, L. & Cryan, J. F. (2017). Stress and the gut-brain axis ∞ Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of Stress, 7, 124-136.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a biological framework for understanding the deep connection between what you eat, how you feel, and how your body responds to powerful therapeutic interventions. It moves the conversation about anxiety away from a narrative of personal failing and toward one of biochemical opportunity.

The sensations you experience are real, valid, and rooted in the intricate systems that govern your physiology. The knowledge that you can directly influence these systems through conscious, personalized dietary choices is a profound form of agency.

This is the beginning of a more refined dialogue with your own body. The goal is to learn its unique language of signals and needs. The path to optimizing your health and well-being is not about adopting a rigid, one-size-fits-all diet.

It is about becoming a careful observer of your own experience, correlating how different nutritional inputs affect your energy, your cognitive clarity, and your emotional state. This journey of self-study, ideally guided by clinical expertise and objective data, is where true personalization occurs. You possess the capacity to become an active, informed architect of your own biological reality.