Fundamentals

You may feel a persistent, low-grade sense of dysfunction, a state where vitality seems just out of reach. This experience of fatigue, cognitive fog, or unexplained weight gain is a valid biological signal. Your body is communicating a state of imbalance, a disruption in its intricate internal messaging service.

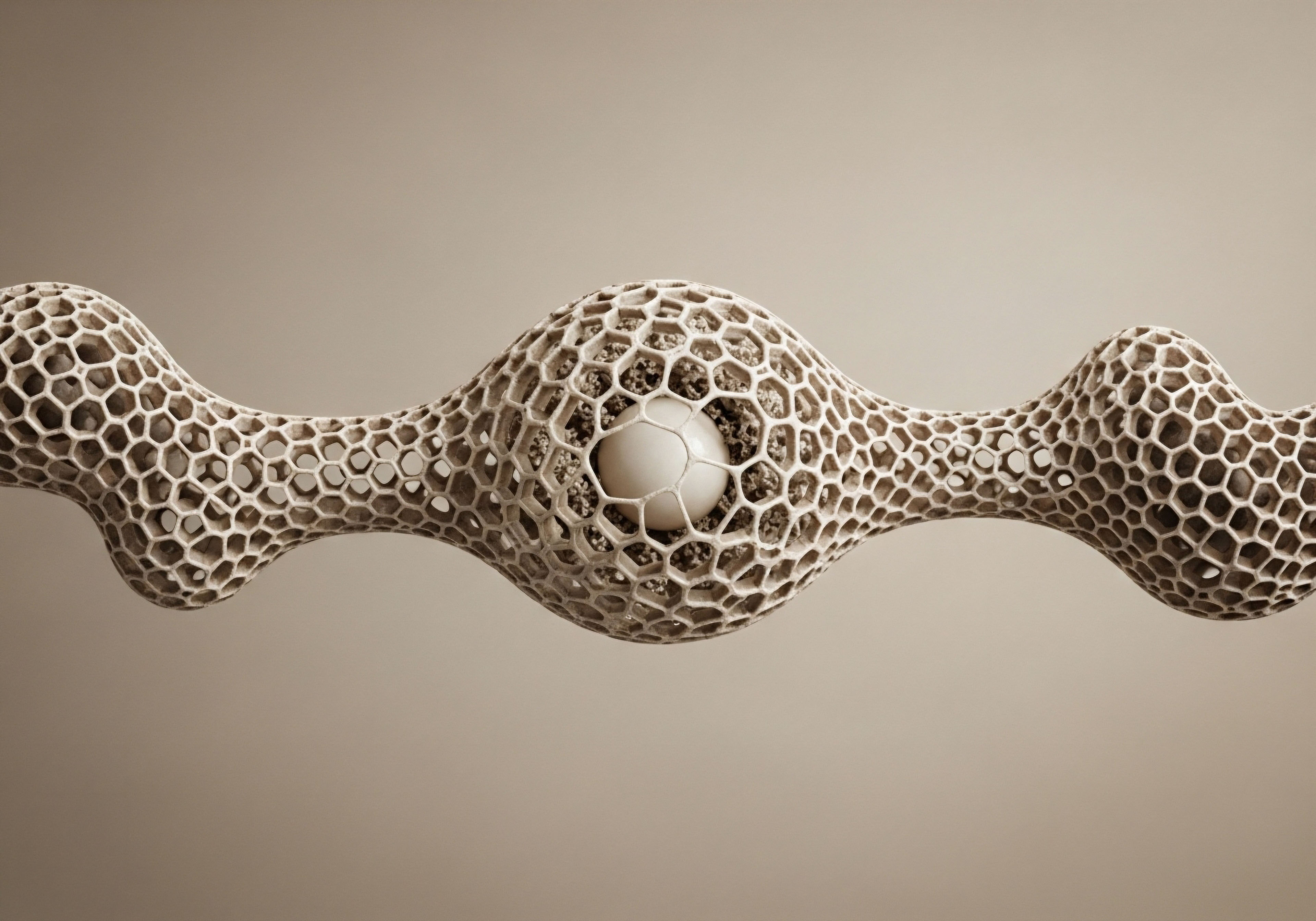

This internal communication network, the endocrine system, relies on precise hormonal signals to regulate everything from your metabolism and mood to your reproductive health. The feeling of being unwell without a clear diagnosis often points toward a subtle, yet persistent, interference with this system from outside sources.

Our modern environment contains a vast array of chemical compounds, some of which are structurally similar to our own hormones. These substances, known as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), are found in everyday materials like plastics, canned food linings, and personal care products.

When they enter the body, they can occupy hormone receptors, sending faulty signals or blocking correct ones. This process is akin to a stranger using a copied key to enter a secure building; they may not know the security protocols, but their presence alone creates chaos and disrupts the building’s operations. The body’s hormonal symphony, which requires precision and timing, becomes discordant.

The Body’s Internal Signaling Network

Think of your hormones as a highly sophisticated postal service, delivering specific instructions to trillions of cells. Testosterone, for instance, carries a message to muscle cells to initiate protein synthesis. Estrogen instructs uterine cells during the menstrual cycle. This system operates on a delicate feedback loop, a biological conversation where glands listen and respond to circulating hormone levels to maintain equilibrium.

The hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain act as the central post office, directing the flow of these chemical messengers throughout the body.

EDCs interfere directly with this mail delivery. A xenoestrogen, a type of EDC that mimics estrogen, can bind to an estrogen receptor. Because it is not the body’s native estrogen, the signal it sends may be too strong, too weak, or timed incorrectly. This creates a state of confusion at the cellular level.

Over time, this persistent miscommunication can manifest as tangible symptoms, affecting energy levels, body composition, and overall well-being. The challenge, and the opportunity, lies in understanding how to support the body’s innate ability to identify and remove these disruptive agents.

What Are the Body’s Defenses?

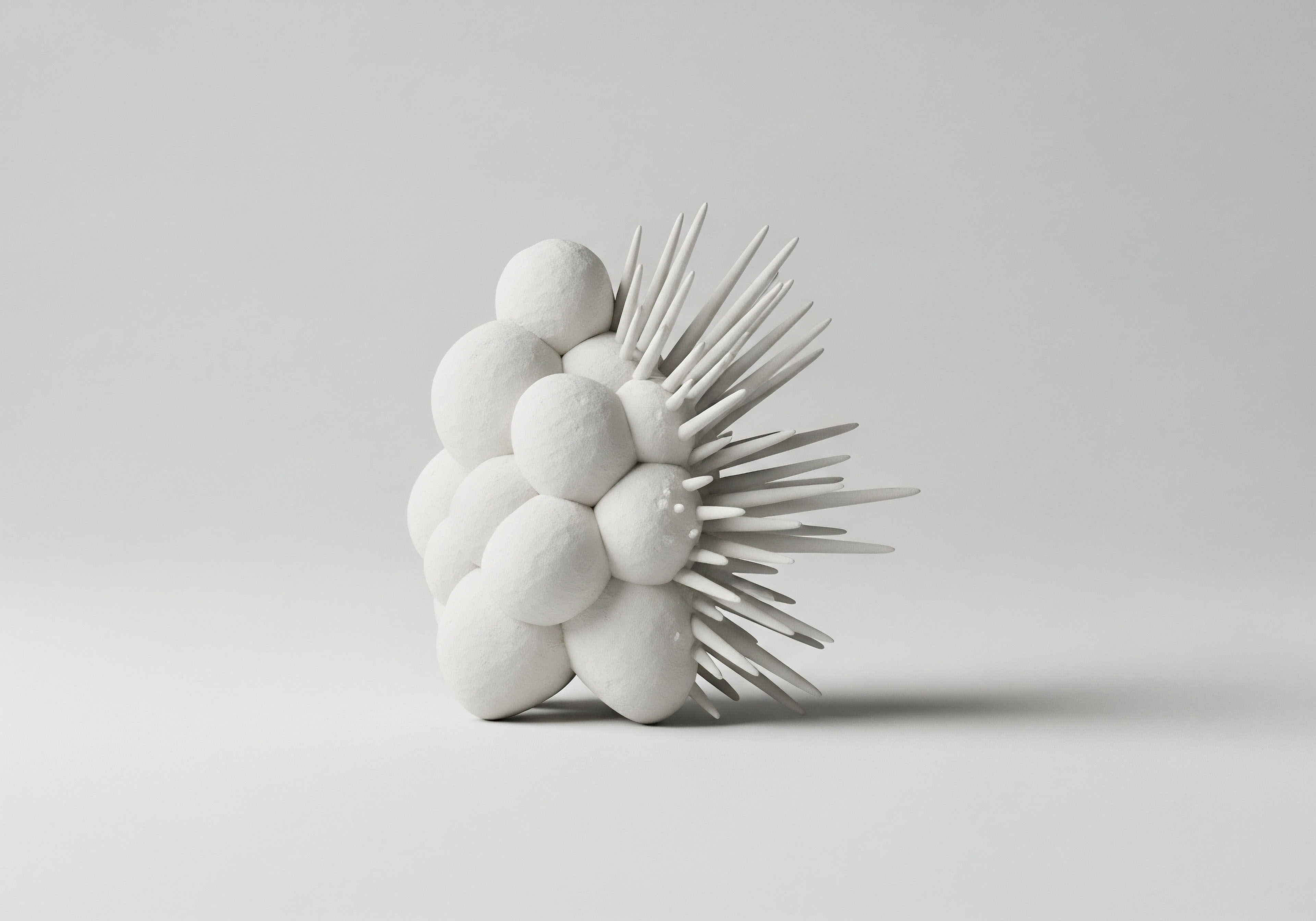

Your body possesses a powerful, built-in system for detoxification, primarily managed by the liver. This organ works in two distinct phases to process and prepare unwanted compounds for removal. Phase I detoxification involves a family of enzymes that chemically transform a toxin to make it more water-soluble.

Phase II then attaches another molecule to this transformed compound, neutralizing it and packaging it for excretion through urine or bile. For this system to function optimally, it requires a steady supply of specific nutrients.

A healthy detoxification system is the foundation for hormonal resilience against environmental exposures.

When the detoxification pathways are overburdened by a high volume of EDCs and lack the necessary nutritional cofactors, these disruptive chemicals can accumulate. This accumulation is a direct contributor to the hormonal dysregulation you may be experiencing. The path to restoring balance, therefore, begins with providing targeted nutritional support to enhance the efficiency of these natural purification processes.

By doing so, you give your body the resources it needs to clear the static and restore clear communication within its endocrine network.

Intermediate

To counteract the effects of environmental hormonal interference, a two-pronged approach is required. The first objective is to reduce your exposure load, which can be achieved through conscious consumer choices. The second, more dynamic objective is to enhance the body’s metabolic machinery for neutralizing and eliminating these compounds.

This involves a deep look at the liver’s detoxification circuits and the role of the gut microbiome in hormonal regulation. Specific dietary interventions can supply the precise molecular tools these systems need to function with high efficiency.

Dietary adjustments can significantly reduce the amount of EDCs your body has to process. Shifting away from processed foods and those packaged in plastics can lower your intake of phthalates and bisphenol A (BPA). Choosing fresh, organic produce helps minimize exposure to pesticides and herbicides with endocrine-disrupting properties. These lifestyle changes are the first line of defense, lightening the burden on your internal detoxification systems.

The Liver’s Two-Phase Detoxification System

The liver is the central processing hub for metabolic detoxification. Its operations are divided into two sequential phases. Understanding their distinct functions reveals why certain nutrients are so effective.

- Phase I Detoxification ∞ This is the initial transformation step. Cytochrome P450 enzymes modify the chemical structure of a toxin, often through oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis. This process makes the compound more reactive, preparing it for Phase II. While necessary, this step can sometimes create intermediate metabolites that are more toxic than the original substance. A steady supply of B vitamins and antioxidants is needed to keep this phase running smoothly and to protect the liver from oxidative damage.

- Phase II Detoxification ∞ This is the conjugation phase, where the body neutralizes the reactive metabolites from Phase I. Specific enzymes attach small molecules to the toxin, rendering it water-soluble and non-toxic, ready for excretion. Key conjugation pathways include glucuronidation, sulfation, and glutathione conjugation. This phase is heavily dependent on the availability of amino acids and sulfur-containing compounds.

Nutritional interventions work by providing the specific substrates and cofactors needed for these enzymatic reactions. For instance, compounds from cruciferous vegetables are known to support both phases, ensuring that toxins are not only transformed but also safely neutralized and removed.

Key Phytonutrients for Hormonal Recalibration

Certain plant-derived compounds have demonstrated a remarkable ability to support the body’s management of hormones and xenoestrogens. These phytonutrients work by directly supporting the detoxification pathways responsible for their clearance.

| Phytonutrient Class | Primary Source | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Isothiocyanates (e.g. Sulforaphane) | Broccoli sprouts, Cabbage, Kale | Potently upregulates Phase II detoxification enzymes, particularly via the Nrf2 pathway, and may aid in reducing harmful BPA accumulation. |

| Indoles (e.g. Diindolylmethane – DIM) | Broccoli, Cauliflower, Brussels sprouts | Supports Phase I detoxification and promotes a healthier metabolism of estrogen, shifting the balance toward less potent estrogen metabolites. |

| Lignans (Phytoestrogens) | Flaxseeds, Sesame seeds | Competitively binds to estrogen receptors, which can block more potent xenoestrogens from exerting their effects. They also support gut health. |

| Polyphenols (e.g. Resveratrol, Curcumin) | Grapes, Berries, Turmeric | Provide powerful antioxidant support, protecting liver cells from damage during Phase I detoxification and reducing systemic inflammation. |

The Estrobolome Your Gut’s Role in Hormone Balance

The gut microbiome contains a specific collection of bacteria known as the estrobolome. These microbes produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase, which plays a direct role in estrogen circulation. After the liver conjugates estrogen in Phase II (a process called glucuronidation) and sends it to the gut for excretion, the estrobolome gets involved. A balanced gut microbiome keeps beta-glucuronidase activity in check, allowing the bound estrogen to be safely eliminated from the body in stool.

Your gut health is inextricably linked to your hormonal health through the microbial metabolism of estrogens.

An imbalanced gut microbiome, or dysbiosis, can lead to an overproduction of beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme can break the bond between estrogen and its conjugate, freeing the estrogen to be reabsorbed back into the bloodstream. This recirculation contributes to an overall excess of estrogen, compounding the issues caused by environmental xenoestrogens. Therefore, supporting gut health with fiber, prebiotics, and probiotics is a foundational strategy for ensuring proper hormonal excretion.

Academic

The capacity for nutritional interventions to reverse environmentally induced hormonal dysregulation is grounded in the biochemical and molecular mechanisms governing xenobiotic metabolism and endocrine signaling. The primary targets for these interventions are the enzymatic pathways of the liver, the genetic regulation of these pathways, and the metabolic activity of the gut microbiome. A systems-biology perspective reveals a deeply interconnected network where specific phytonutrients act as potent signaling molecules, capable of modulating gene expression and enzymatic activity to restore homeostasis.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates exert their pathological effects by interacting with nuclear receptors, including estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) and androgen receptors (AR). BPA, for example, acts as an ER agonist and an AR antagonist, thereby disrupting the sensitive balance of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis.

This can lead to suppressed testosterone production in men and altered estrogenic activity in both sexes. The reversal of these effects depends on the body’s ability to recognize, metabolize, and excrete these foreign compounds efficiently.

Molecular Mechanisms of Phytonutrient-Mediated Detoxification

The most powerful nutritional interventions operate at the level of genetic transcription, influencing the very blueprint for the body’s detoxification enzymes. The Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway is a primary regulator of cellular defense against oxidative stress and xenobiotics.

Sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate derived from cruciferous vegetables, is one of the most potent known natural activators of the Nrf2 pathway. In its inactive state, Nrf2 is bound in the cytoplasm. Upon exposure to an activator like sulforaphane, Nrf2 is released, translocates to the nucleus, and binds to a DNA sequence known as the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE).

This binding event initiates the transcription of a suite of over 200 cytoprotective genes, including those for critical Phase II enzymes like glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs). This upregulation directly enhances the capacity of the liver to conjugate and neutralize EDCs and their reactive metabolites. Studies have demonstrated that sulforaphane can specifically mitigate the accumulation of BPA in tissues, highlighting its direct utility in reversing environmental hormonal disruption.

Diindolylmethane (DIM), a metabolite of indole-3-carbinol, exhibits a different but complementary mechanism. DIM primarily modulates the activity of Phase I cytochrome P450 enzymes, specifically CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1. It promotes a metabolic shift in estrogen breakdown, favoring the production of 2-hydroxyestrone (2-OHE1), a weaker and potentially protective estrogen metabolite, over the more potent and proliferative 16α-hydroxyestrone (16α-OHE1).

By altering the metabolic fate of endogenous estrogens, DIM helps to lower the overall estrogenic load on the body, making the system more resilient to the added burden of xenoestrogens.

Targeted phytonutrients function as epigenetic modulators, altering the expression of genes central to detoxification and hormone metabolism.

How Does the Gut Microbiome Regulate Estrogen Clearance?

The estrobolome’s regulation of circulating estrogens is a critical control point for hormonal health. The process of glucuronidation in the liver attaches glucuronic acid to estrogen, marking it for excretion. Gut bacteria that produce high levels of the enzyme beta-glucuronidase can cleave this bond, effectively reactivating the estrogen for reabsorption into enterohepatic circulation.

Nutritional interventions that modify the gut microbiome can therefore have a profound impact on systemic estrogen levels. A diet rich in fiber and prebiotics (e.g. inulin from garlic and onions) promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. These species tend to produce less beta-glucuronidase, thereby favoring the excretion of conjugated estrogens.

Furthermore, dietary lignans, found abundantly in flaxseeds, are metabolized by gut bacteria into enterolactone and enterodiol. These compounds are themselves weak phytoestrogens that can competitively inhibit the binding of more potent EDCs to estrogen receptors, providing an additional layer of protection.

| Intervention | Molecular Target | Primary Biological Outcome | Relevance to EDC Disruption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulforaphane | Nrf2 Transcription Factor | Upregulation of Phase II enzymes (GST, UGT) | Enhanced clearance of EDCs and their metabolites. |

| Diindolylmethane (DIM) | CYP450 Enzymes (Phase I) | Modulation of estrogen metabolism pathways | Reduces total estrogenic load, improving resilience. |

| Dietary Fiber & Prebiotics | Gut Microbiome Composition | Reduced beta-glucuronidase activity | Prevents reabsorption of estrogen, promoting excretion. |

| Lignans | Estrogen Receptors & Gut Flora | Competitive receptor binding by enterolignans | Blocks EDCs from binding to their target receptors. |

What Are the Implications for Clinical Protocols?

The presence of a high EDC load can suppress endogenous hormone production, creating a clinical picture that might lead to interventions like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) in men or hormonal support in women. For example, the anti-androgenic effects of phthalates and the estrogenic effects of BPA can impair Leydig cell function and suppress testosterone synthesis.

While protocols like TRT can restore hormonal balance by providing exogenous hormones, they do not address the root cause of the environmental interference. A foundational nutritional protocol aimed at enhancing EDC detoxification can be viewed as a complementary strategy. By clearing the disruptive signals, the body’s own endocrine axes may have a greater capacity to restore their natural function, potentially improving the efficacy of clinical protocols or, in some cases, reducing the need for them.

References

- Gore, A. C. et al. “Executive Summary to EDC-2 ∞ The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 36, no. 6, 2015, pp. 593-602.

- Erkekoglu, Pinar, and Belma Kocer-Gumusel. “Environmental Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals ∞ A Special Focus on Phthalates and Bisphenol A.” Environmental Health Risk – Hazardous Factors to Living Species, edited by Marcelo L. Larramendy and Sonia Soloneski, IntechOpen, 2016.

- Baker, J. M. et al. “Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

- Fucic, A. et al. “Environmental exposure to xenoestrogens and oestrogen related cancers ∞ reproductive system, breast, lung, kidney, pancreas, and brain.” Environmental Health, vol. 11, suppl. 1, 2012, p. S8.

- Elgar, Karin. “Sulforaphane (SFN), 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) and indole-3-carbinol (I3C) ∞ A Review of Clinical Use and Efficacy.” Nutritional Medicine Journal, vol. 1, no. 2, 2022, pp. 81-96.

- Hodges, Romilly E. and Deanna M. Minich. “Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components ∞ A Scientific Review with Clinical Application.” Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, vol. 2015, 2015, Article ID 760689.

- Patel, S. et al. “The role of endocrine-disrupting phthalates and bisphenols in cardiometabolic disease ∞ the evidence is mounting.” Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, vol. 28, no. 4, 2021, pp. 412-423.

- Qi, X. et al. “The gut microbiota-bile acid-interleukin-22 axis orchestrates defence against bactericidal proteins in the intestine.” Nature Communications, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, p. 331.

- Kalyanacutty, K. et al. “The role of the gut microbiome in the development of obesity and associated metabolic diseases.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 10, no. 11, 2021, p. 2497.

- Di Zazzo, E. et al. “Risks and benefits related to alimentary exposure to xenoestrogens.” Journal of Food Science and Technology, vol. 54, no. 12, 2017, pp. 3773-3787.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here provides a map of the biological terrain connecting your environment to your internal chemistry. It details the pathways, identifies the disruptive agents, and illuminates the molecular tools available for restoring balance. This knowledge shifts the perspective from one of passive suffering to one of active participation in your own health. You now have an understanding of the conversation happening between your cells and the signals they receive from the world around you.

The next step in this process is one of introspection and observation. How do these systems manifest in your own life? What aspects of your daily routine contribute to your total environmental load? And how might you begin to introduce these nutritional strategies in a way that aligns with your own body’s unique needs?

This is not a protocol to be followed rigidly, but a set of principles to be applied with awareness. Your personal health journey is a dynamic, evolving process. The ultimate goal is to cultivate a deep understanding of your own biological system, allowing you to make informed, personalized decisions that reclaim your vitality and function without compromise.

Glossary

detoxification pathways

hormonal dysregulation

gut microbiome

phthalates

bpa

nutritional interventions

xenoestrogens

estrobolome

estrogen receptors

nrf2 pathway

sulforaphane