Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A persistent fatigue that sleep doesn’t touch, a subtle shift in your mood, or the sense that your body is no longer responding as it once did. These experiences are valid and deeply personal, and they often signal a disruption within your body’s intricate communication network ∞ the endocrine system.

The hormones produced by this system are the body’s internal messengers, orchestrating everything from your metabolism and energy levels to your reproductive health and stress response. When this system is compromised, the effects ripple through your entire sense of well-being.

A foundational element of this entire process, one that is frequently overlooked in the rush of modern life, is the availability of specific micronutrients. These vitamins and minerals are the essential raw materials, the very building blocks, required for the synthesis of these critical hormones.

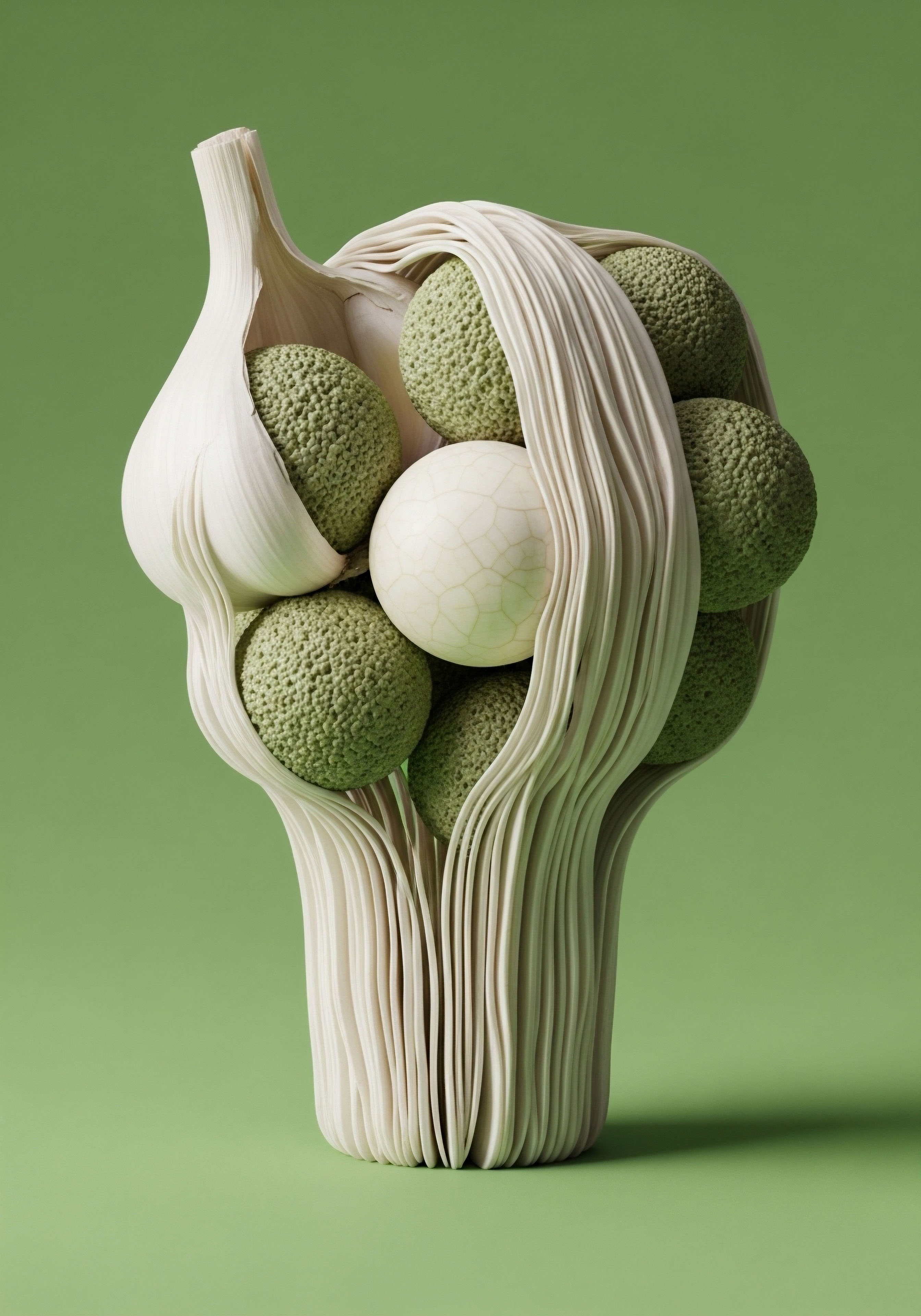

The endocrine system does not operate on willpower alone; it is a biological factory that depends on a precise inventory of resources. Each hormone, whether it’s testosterone, estrogen, or thyroid hormone, has a unique molecular structure built from precursors like cholesterol and amino acids.

The enzymatic reactions that convert these precursors into their final, active forms are entirely dependent on specific vitamin and mineral cofactors. A deficiency in one of these key nutrients is akin to a critical supply chain failure.

The production line for a specific hormone can slow down or halt altogether, not from a lack of demand, but from a simple absence of a necessary part. This is where the connection between your diet and your hormonal vitality becomes undeniably clear. Understanding this link is the first step in moving from passively experiencing symptoms to proactively addressing the root cause of the imbalance.

Nutrient availability is a critical factor directly influencing the body’s capacity to produce and regulate its hormonal messengers.

This is not about achieving dietary perfection. It is about recognizing that your body’s ability to create the hormones that govern your daily life is directly tied to the nutritional resources you provide it. Chronic stress, for instance, can deplete stores of B vitamins and magnesium, which are crucial for producing cortisol, the primary stress hormone.

This depletion creates a cascade effect, impairing other hormonal pathways that rely on the same nutrients. Similarly, insufficient dietary zinc can directly impede testosterone production, leading to symptoms like low libido and reduced muscle mass. These are not isolated incidents but examples of a systemic principle ∞ your hormonal health is inextricably linked to your nutritional status.

By viewing your body through this lens, you begin a journey of reclaiming function, not by fighting against your biology, but by providing it with the essential tools it needs to perform its duties.

Intermediate

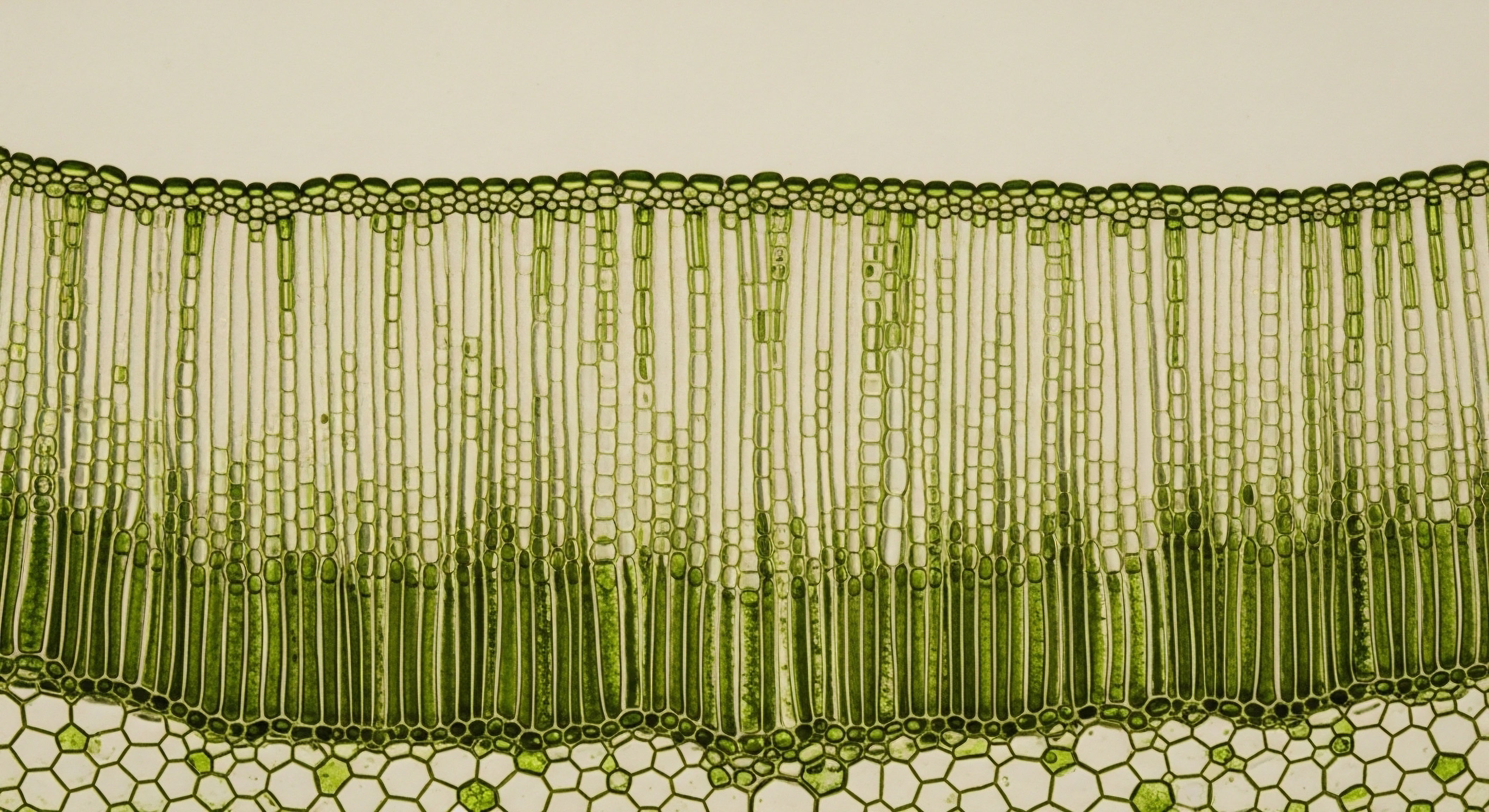

To truly grasp how nutritional status governs endocrine function, we must move beyond simple associations and examine the precise biochemical roles of micronutrients within the hormonal production pathways. These vitamins and minerals are not passive ingredients; they are active participants, serving as indispensable cofactors for the enzymes that drive hormonal synthesis.

Without these cofactors, the complex, multi-step processes of converting raw materials into biologically active hormones cannot proceed efficiently. This is the mechanistic “why” behind the fatigue, mood shifts, and metabolic changes that so many experience. It is a direct consequence of a breakdown in the body’s internal manufacturing process.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis and Key Minerals

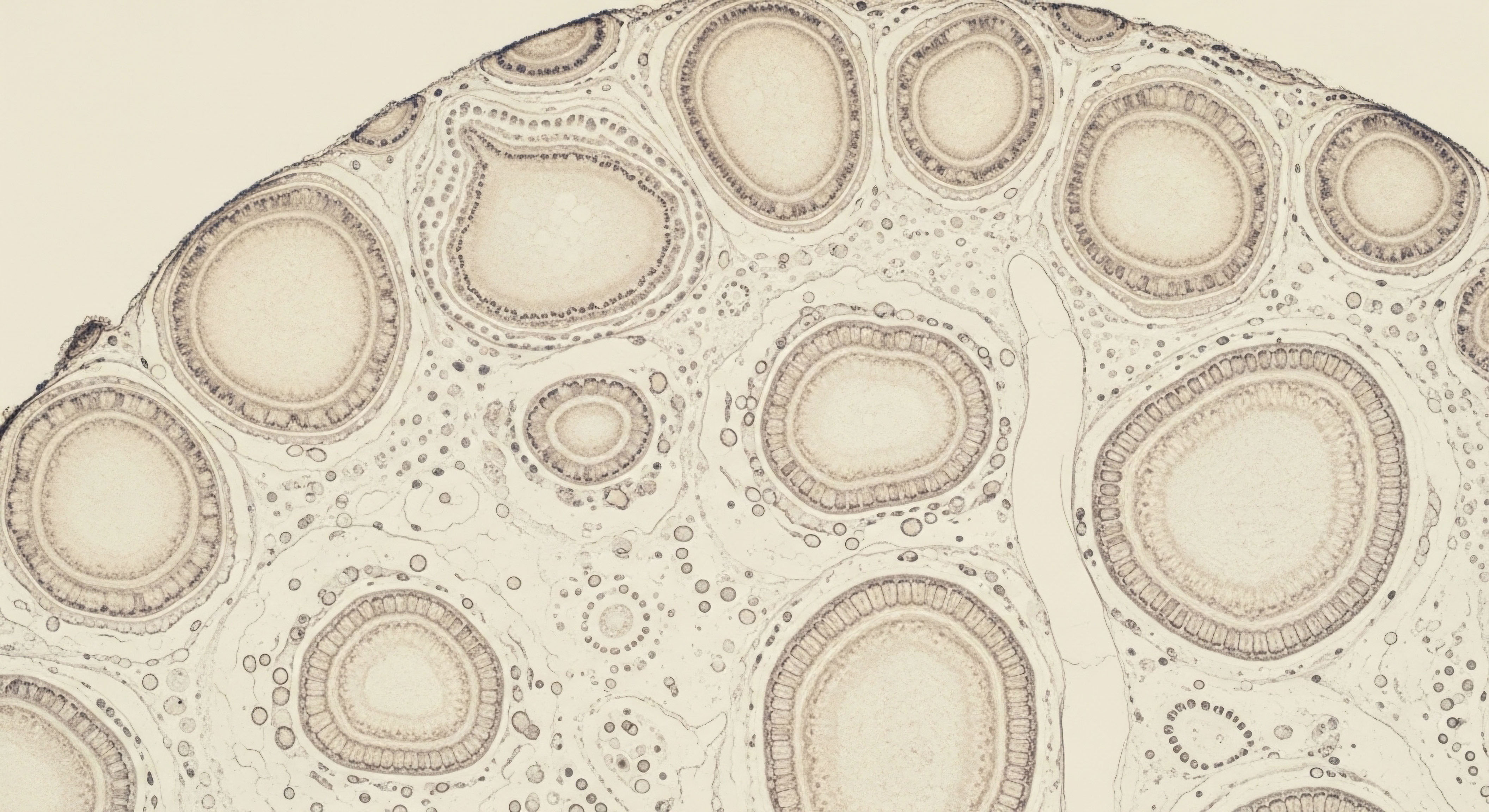

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis is the central command system for reproductive health, regulating the production of testosterone in men and estrogen in women. Its function is exquisitely sensitive to the availability of certain minerals, particularly zinc and magnesium.

Zinc, for example, is a critical component of the enzymes involved in steroidogenesis, the metabolic pathway that produces steroid hormones. It also plays a role in the function of the 5-alpha-reductase enzyme, which converts testosterone into its more potent form, dihydrotestosterone (DHT). A deficiency in zinc can therefore lead to a direct reduction in testosterone synthesis and activity. This can manifest as hypogonadism, a condition characterized by low testosterone levels and associated symptoms.

Magnesium complements the role of zinc by influencing the activity of the HPG axis and modulating the body’s stress response. Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels, which can suppress the HPG axis and lower testosterone production. Magnesium helps regulate the stress response, potentially mitigating the negative impact of cortisol on hormonal balance. Furthermore, magnesium supplementation has been shown to improve the testosterone-to-cortisol ratio, a key indicator of anabolic versus catabolic state in the body.

The HPG axis, the master regulator of sex hormone production, is highly dependent on adequate levels of zinc and magnesium to function optimally.

How Does Vitamin D Influence Hormone Levels?

Vitamin D, often referred to as the “sunshine vitamin,” functions more like a prohormone in the body, with receptors found in numerous tissues, including the testes and ovaries. Its role in hormonal health is profound, particularly in the context of testosterone production. Studies have demonstrated a direct correlation between vitamin D levels and testosterone concentrations in men.

Laboratory research has shown that treating testicular tissue with activated vitamin D results in increased testosterone production, indicating a direct stimulatory effect. Men with vitamin D deficiency are more likely to have lower testosterone levels, and supplementation has been shown in some studies to increase total testosterone. This highlights the importance of maintaining adequate vitamin D status for supporting androgen production and overall male hormonal health.

The following table illustrates the specific roles of key micronutrients in the synthesis of major hormones, providing a clear overview of their importance.

| Hormone Class | Key Micronutrients | Biochemical Role |

|---|---|---|

| Steroid Hormones (Testosterone, Estrogen) | Zinc, Magnesium, Vitamin D | Cofactors for steroidogenesis enzymes; modulation of the HPG axis; direct stimulation of hormone production. |

| Thyroid Hormones (T3, T4) | Iodine, Selenium, Iron | Essential component of hormone structure (iodine); cofactor for deiodinase enzymes (selenium) and thyroid peroxidase (iron). |

| Stress Hormones (Cortisol) | B Vitamins, Magnesium | Cofactors in the enzymatic pathways for cortisol synthesis; regulation of the stress response. |

The Thyroid Gland’s Reliance on Iodine and Selenium

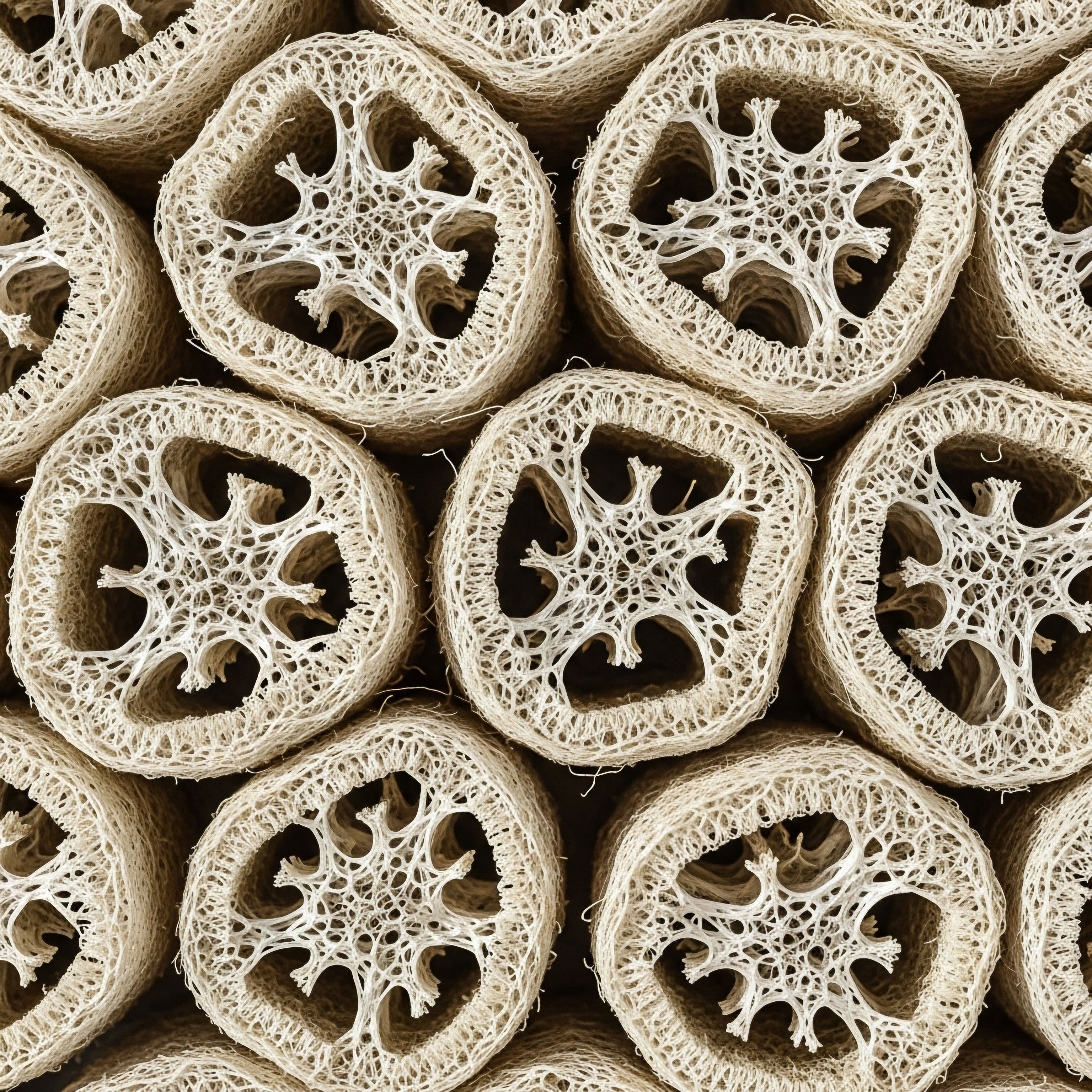

The thyroid gland regulates the body’s metabolic rate through the production of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). This process is entirely dependent on a consistent supply of iodine and selenium. Iodine is the fundamental building block of thyroid hormones; the numbers in T4 and T3 refer to the number of iodine atoms in each molecule.

Without sufficient iodine, the thyroid gland cannot produce these hormones, leading to hypothyroidism and potentially the development of a goiter as the gland enlarges in an attempt to capture more iodine from the bloodstream.

Selenium’s role is equally critical, though more nuanced. It is a key component of the deiodinase enzymes, which are responsible for converting the relatively inactive T4 into the highly active T3 in peripheral tissues. Selenium deficiency can impair this conversion, leading to a functional hypothyroidism even if T4 levels are adequate.

Furthermore, the process of thyroid hormone synthesis generates hydrogen peroxide, a reactive oxygen species that can damage thyroid tissue. Selenium-dependent enzymes like glutathione peroxidase are essential for neutralizing this oxidative stress, protecting the gland from damage.

- Iodine ∞ Serves as the primary structural component of thyroid hormones T4 and T3.

- Selenium ∞ Acts as a cofactor for deiodinase enzymes that convert T4 to active T3 and protects the thyroid gland from oxidative damage.

- Iron ∞ A necessary cofactor for the enzyme thyroid peroxidase (TPO), which is essential for the iodination of thyroglobulin, a key step in hormone synthesis.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of endocrine function requires a systems-biology perspective, viewing hormonal pathways not as isolated chains of command but as an interconnected web of metabolic and signaling networks. Nutritional biochemistry provides the lens through which we can analyze the molecular underpinnings of this system.

The availability of micronutrients as enzymatic cofactors represents a rate-limiting step in numerous endocrine processes, from the synthesis of neurotransmitters that initiate hormonal cascades in the hypothalamus to the final conversion of prohormones into their active forms in peripheral tissues. Examining the role of B-complex vitamins offers a compelling case study in this intricate dependency.

What Is the Role of B Vitamins in Hormonal Precursor Synthesis?

The B-complex vitamins function as essential coenzymes in a vast array of metabolic pathways, including those that generate the foundational molecules for hormone production. For example, pantothenic acid (Vitamin B5) is a component of Coenzyme A (CoA), a molecule central to the metabolism of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

Acetyl-CoA, derived from these macronutrients, is the primary precursor for the synthesis of cholesterol, which in turn serves as the backbone for all steroid hormones, including testosterone, estrogen, and cortisol. A deficiency in Vitamin B5 could, therefore, theoretically limit the available pool of cholesterol for steroidogenesis, creating a bottleneck at the very beginning of the hormonal production line.

Similarly, Vitamin B6, in its active form pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), is a critical cofactor for over 100 enzymatic reactions, many of which involve amino acid metabolism. This includes the synthesis of neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin, which modulate the release of hormones from the pituitary gland.

An imbalance in these neurotransmitters can disrupt the entire HPG axis. Furthermore, B vitamins like folate (B9) and cobalamin (B12) are integral to one-carbon metabolism, a set of pathways essential for DNA synthesis and methylation. These processes are vital for the cellular health and function of all endocrine glands, ensuring they can respond appropriately to signaling hormones.

The B-complex vitamins are not merely supportive nutrients; they are integral components of the enzymatic machinery that synthesizes the precursors and modulators of all major hormonal classes.

The following table details the specific coenzymatic functions of key B vitamins within endocrine-related metabolic pathways, illustrating their indispensable role.

| B Vitamin | Coenzyme Form | Primary Metabolic Function in Endocrine Health |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B5 (Pantothenic Acid) | Coenzyme A (CoA) | Essential for the synthesis of acetyl-CoA, the precursor to cholesterol and all steroid hormones. |

| Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) | Pyridoxal Phosphate (PLP) | Cofactor for neurotransmitter synthesis (dopamine, serotonin), which regulates pituitary hormone release. |

| Vitamin B9 (Folate) & B12 (Cobalamin) | Tetrahydrofolate & Methylcobalamin | Key roles in one-carbon metabolism, essential for DNA synthesis, methylation, and the health of endocrine tissues. |

| Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) | FAD and FMN | Cofactor for enzymes in the electron transport chain and in the conversion of other B vitamins (like B6 and folate) to their active forms. |

The Interplay of Nutrients and the HPA Axis

The Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system, provides another clear example of nutrient-hormone interdependence. The synthesis of cortisol in the adrenal glands is a multi-step enzymatic process that requires a continuous supply of B vitamins.

Chronic stress can increase the demand for these vitamins, potentially leading to a state of relative deficiency. This can impair the body’s ability to mount an effective cortisol response, leading to dysregulation of the HPA axis. This dysregulation has far-reaching consequences, as cortisol influences everything from blood sugar regulation and immune function to the activity of other hormonal systems like the HPG and HPT (Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid) axes.

Zinc deficiency has also been shown to enhance HPA axis activity, leading to elevated glucocorticoid secretion. This suggests a complex feedback loop where nutrient status not only supports hormone production but also modulates the activity of the central regulatory axes.

The intricate relationship between micronutrients and the endocrine system underscores the importance of a holistic, systems-based approach to hormonal health. It is a biochemical reality that cannot be ignored when addressing the complex symptomatology of endocrine dysfunction. The efficiency of the entire system, from central command to peripheral action, is fundamentally reliant on the raw materials provided by a nutrient-replete diet.

- Vitamin B5 ∞ Its role in forming Coenzyme A is a rate-limiting step for producing the cholesterol needed for steroid hormone synthesis.

- Vitamin B6 ∞ Essential for creating the very neurotransmitters that signal the start of hormonal cascades in the brain.

- Zinc ∞ Modulates the activity of the HPA axis, demonstrating that minerals can influence the central control of hormonal systems.

References

- Baltaci, Abdulkerim Kasim, et al. “The role of zinc in the endocrine system.” Journal of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, vol. 32, no. 1, 2019, pp. 231-239.

- Brilla, L.R. and Victor Conte. “Effects of a Novel Zinc-Magnesium Formulation on Hormones and Strength.” Journal of Exercise Physiology Online, vol. 3, no. 4, 2000, pp. 26-36.

- D’Aniello, G. et al. “The role of selenium in thyroid hormone metabolism and effects of selenium deficiency on thyroid hormone and iodine metabolism.” Biological Trace Element Research, vol. 20, no. 1-2, 1989, pp. 151-62.

- Kennedy, David O. “B Vitamins and the Brain ∞ Mechanisms, Dose and Efficacy ∞ A Review.” Nutrients, vol. 8, no. 2, 2016, p. 68.

- Pilz, S. et al. “Effect of vitamin D supplementation on testosterone levels in men.” Hormone and Metabolic Research, vol. 43, no. 3, 2011, pp. 223-225.

- Takeda, Tomimitsu, et al. “Behavioral Abnormality Induced by Enhanced Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Axis Activity under Dietary Zinc Deficiency and Its Usefulness as a Model.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 21, no. 22, 2020, p. 8768.

- Wehr, E. et al. “Vitamin D and Testosterone in Healthy Men ∞ A Randomized Controlled Trial.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 101, no. 7, 2016, pp. 2945-2954.

- Zimmermann, Michael B. and Josef Köhrle. “The Impact of Iron and Selenium Deficiencies on Iodine and Thyroid Metabolism ∞ Biochemistry and Relevance to Public Health.” Thyroid, vol. 12, no. 10, 2002, pp. 867-78.

- Rude, R.K. et al. “Magnesium deficiency-induced osteoporosis in the rat ∞ uncoupling of bone formation and resorption.” Magnesium Research, vol. 12, no. 4, 1999, pp. 257-67.

- Prasad, Ananda S. “Zinc in Human Health ∞ Effect of Zinc on Immune Cells.” Molecular Medicine, vol. 14, no. 5-6, 2008, pp. 353-57.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a biological framework for understanding the profound connection between your internal chemistry and your daily experience. The science validates the reality that feeling your best is contingent upon the intricate processes occurring at a cellular level. This knowledge is a starting point, a map that illuminates the terrain of your own physiology.

The path forward involves translating this understanding into a personalized strategy, recognizing that your body’s specific needs are unique. The journey to reclaiming vitality is one of informed self-awareness, where you become an active participant in the stewardship of your own health, armed with the understanding of what your body requires to function without compromise.

Glossary

endocrine system

stress response

thyroid hormone

testosterone production

hormonal health

zinc and magnesium

testosterone levels

steroid hormones

hpg axis

thyroid hormone synthesis

hormone synthesis

nutritional biochemistry

hormone production

steroidogenesis