Fundamentals

The question of what happens to the data from your wellness program is a deeply personal one. It touches upon the sensitive intersection of your health, your privacy, and your professional life. You may feel a sense of unease, a vulnerability that arises when personal health information is collected within an employment context.

This feeling is valid. Your biological data is an intimate part of who you are, and the thought of it being used to make judgments about your career can be unsettling. The architecture of the laws governing this area is built upon a central principle ∞ your health information is yours, and its use by an employer is strictly limited.

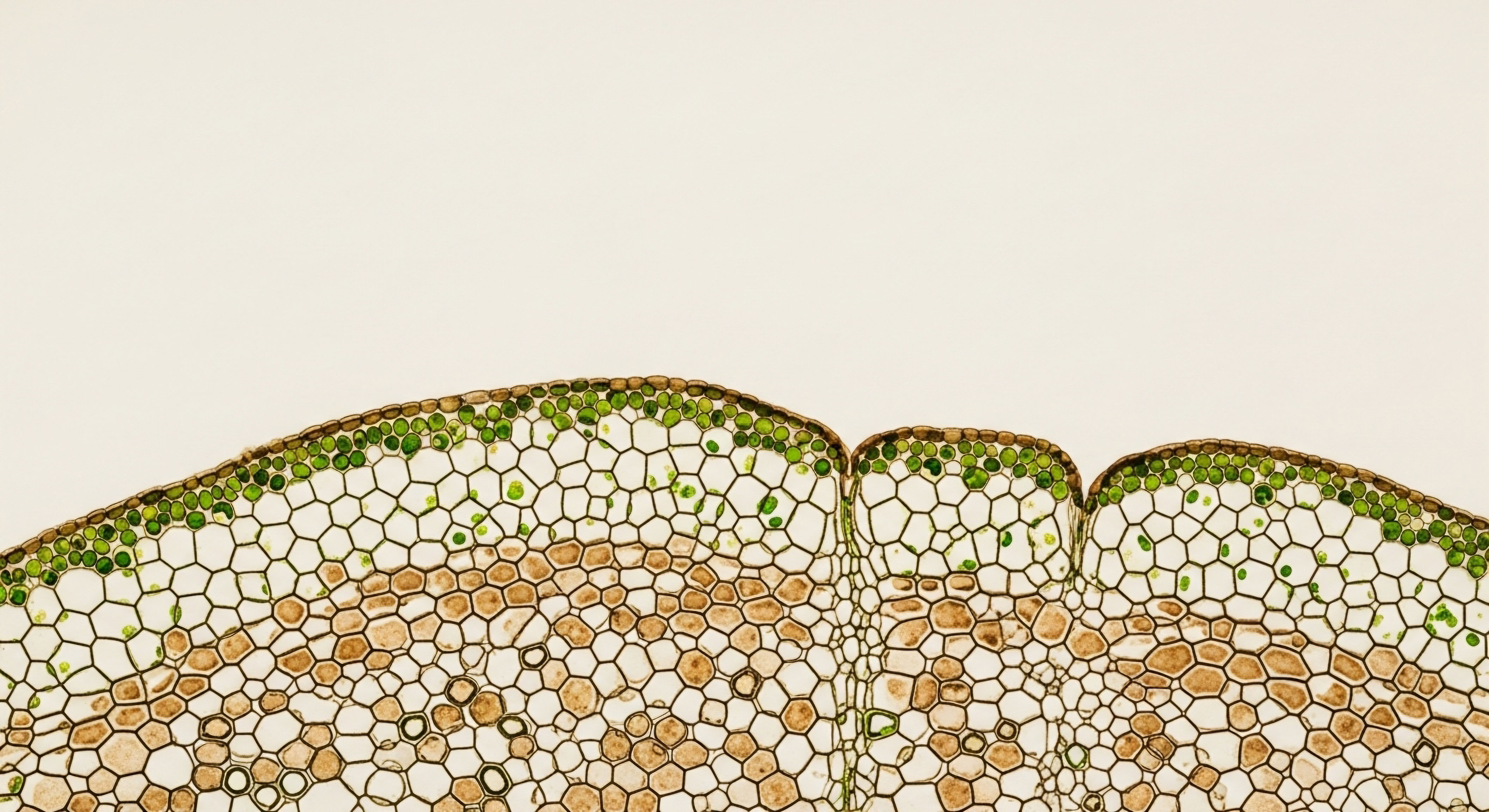

The system is designed to create a firewall between the health data Meaning ∞ Health data refers to any information, collected from an individual, that pertains to their medical history, current physiological state, treatments received, and outcomes observed. gathered in a wellness program and the hands of those who make hiring, firing, or promotion decisions.

At the heart of these protections are three key pieces of federal legislation in the United States ∞ the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act Meaning ∞ The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) is a federal law preventing discrimination based on genetic information in health insurance and employment. (GINA), and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Each acts as a distinct layer of defense.

HIPAA’s Privacy Rule establishes a national standard for the protection of individually identifiable health information. When a wellness program is part of a group health plan, the information collected is considered Protected Health Information Meaning ∞ Protected Health Information refers to any health information concerning an individual, created or received by a healthcare entity, that relates to their past, present, or future physical or mental health, the provision of healthcare, or the payment for healthcare services. (PHI) and is shielded by these stringent privacy and security rules. This means that, by law, the wellness program vendor or the health plan cannot share your specific health details with your employer in a way that identifies you.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination GINA ensures your genetic story remains private, allowing you to navigate workplace wellness programs with autonomy and confidence. Act provides another crucial safeguard. GINA makes it illegal for employers to use your genetic information when making employment decisions. This includes your family medical history, which might be collected in a Health Risk Assessment (HRA).

The law is clear that your participation in providing such information must be voluntary, and you cannot be penalized or denied benefits for choosing to keep it private. Finally, the Americans with Disabilities Act Meaning ∞ The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), enacted in 1990, is a comprehensive civil rights law prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities across public life. adds a layer of protection related to medical examinations and disability-related inquiries.

The ADA generally prohibits employers from requiring medical exams, but it allows for voluntary exams as part of a wellness program. The key here is the word “voluntary.” The incentives offered for participation cannot be so substantial that they become coercive, effectively punishing those who choose not to participate.

Federal laws are structured to prevent your employer from using your individual wellness program data to make decisions about your job.

Understanding the Data Firewall

The system is designed to ensure that your employer receives only aggregated, de-identified data. Think of it as a report that shows the overall health trends of the workforce without revealing any individual’s status. For example, an employer might learn that 30% of the participating employees have high blood pressure, but they will not know which specific employees have the condition.

This allows the company to tailor its wellness offerings ∞ perhaps by introducing stress management workshops or healthier cafeteria options ∞ without infringing on individual privacy. This process of de-identification is a cornerstone of the legal framework, creating a barrier that separates your personal health journey from your professional evaluation.

This separation is not merely a suggestion; it is a legal requirement. Employers who sponsor group health plans must certify that they will safeguard the information and not use it for discriminatory purposes. The entire structure is predicated on the idea that wellness programs Meaning ∞ Wellness programs are structured, proactive interventions designed to optimize an individual’s physiological function and mitigate the risk of chronic conditions by addressing modifiable lifestyle determinants of health. should be a tool for health promotion, not a mechanism for workforce screening. Your decision to participate is a step toward understanding and managing your own health, and the law is designed to protect that intention.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational legal principles reveals a more complex operational reality. The effectiveness of the barrier between wellness data and employment decisions hinges on the specific structure of the wellness program and the rigorous adherence to legal statutes. While direct use of your data for job-related decisions is prohibited, the interplay between program design, financial incentives, and the definition of “voluntary” participation introduces important subtleties.

The regulatory framework, primarily enforced by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Menopause is a data point, not a verdict. (EEOC) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), attempts to balance the employer’s goal of fostering a healthier workforce with the employee’s right to privacy and non-discrimination. A critical distinction lies in whether a wellness program is “participatory” or “health-contingent.”

- Participatory Programs These generally do not require an individual to meet a health-related standard to earn a reward. An example would be receiving an incentive for simply completing a Health Risk Assessment (HRA) or attending a seminar, regardless of the results or outcomes.

- Health-Contingent Programs These require individuals to satisfy a standard related to a health factor to obtain a reward. This could involve achieving a certain body mass index (BMI), cholesterol level, or blood pressure reading. These programs are subject to stricter rules to ensure they are reasonably designed to promote health and are not a subterfuge for discrimination.

The Role of Financial Incentives

A central point of regulatory focus is the size of financial incentives. The law permits employers to offer incentives to encourage participation, but these incentives must not be so large as to render the program involuntary. Under the ADA and GINA, the EEOC has historically scrutinized incentives to ensure they do not become coercive.

For instance, if the financial penalty for not participating is thousands of dollars, it could be argued that the choice is not truly voluntary for many employees. This has been a subject of legal and regulatory debate, with incentive caps often linked to a percentage of the cost of health insurance premiums. The goal is to find a balance where the incentive is meaningful enough to encourage participation without being punitive for non-participation.

How Is Data Handled in Practice?

When a wellness program is administered through a group health plan, it is a “covered entity” under HIPAA, and the data it collects is Protected Health Information (PHI). The plan can share this information with the employer only in a de-identified, aggregate form.

However, if a wellness program is offered directly by the employer and is not part of the group health plan, HIPAA’s privacy rules may not apply. In such cases, other federal or state privacy laws may govern the confidentiality of the data, but the protections might be different. This structural distinction is paramount. Employees should seek to understand how their company’s program is structured to know which specific set of rules applies.

The nature of a wellness program, whether participatory or health-contingent, dictates the specific legal constraints on its operation and the use of financial incentives.

| Legislation | Primary Function in Wellness Programs | Key Restriction on Employers |

|---|---|---|

| HIPAA | Protects individually identifiable health information within group health plans. | Prohibits the disclosure of Protected Health Information (PHI) to employers for employment decisions. |

| GINA | Prohibits discrimination based on genetic information. | Restricts requesting, requiring, or purchasing genetic information, including family medical history, for employment purposes. |

| ADA | Prohibits discrimination based on disability. | Limits medical inquiries and exams to those that are part of a voluntary employee health program. |

The legal framework also requires that any medical information collected through a wellness program must be kept confidential and stored separately from personnel records. This is a critical administrative safeguard designed to prevent both intentional and unintentional misuse of sensitive health data. The existence of these separate records is a tangible manifestation of the legal “firewall” intended to protect employees.

Academic

A deeper analytical exploration of this issue requires a systems-level view, examining the inherent tensions between public health objectives, corporate financial interests, and the civil rights framework of employment law. The rise of employer-sponsored wellness programs represents a significant shift in the landscape of preventative health, moving it from the clinical setting into the corporate sphere.

This migration raises complex questions about data governance, the commodification of health information, and the potential for subtle, systemic forms of discrimination that may not be immediately apparent.

The legal architecture, while robust on paper, is subject to interpretive pressures and evolving regulatory landscapes. The very definition of “voluntary” under the ADA has been a point of significant contention and litigation. The EEOC’s position has sometimes been at odds with the provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which expanded the allowable size of incentives for health-contingent wellness programs.

This regulatory friction highlights a fundamental philosophical divergence ∞ one perspective views substantial incentives as a pragmatic tool to drive positive health behaviors at a population level, while the other sees them as a potential vector for economic coercion that undermines the ADA’s protection against involuntary medical inquiries.

What Are the Limits of De-Identification?

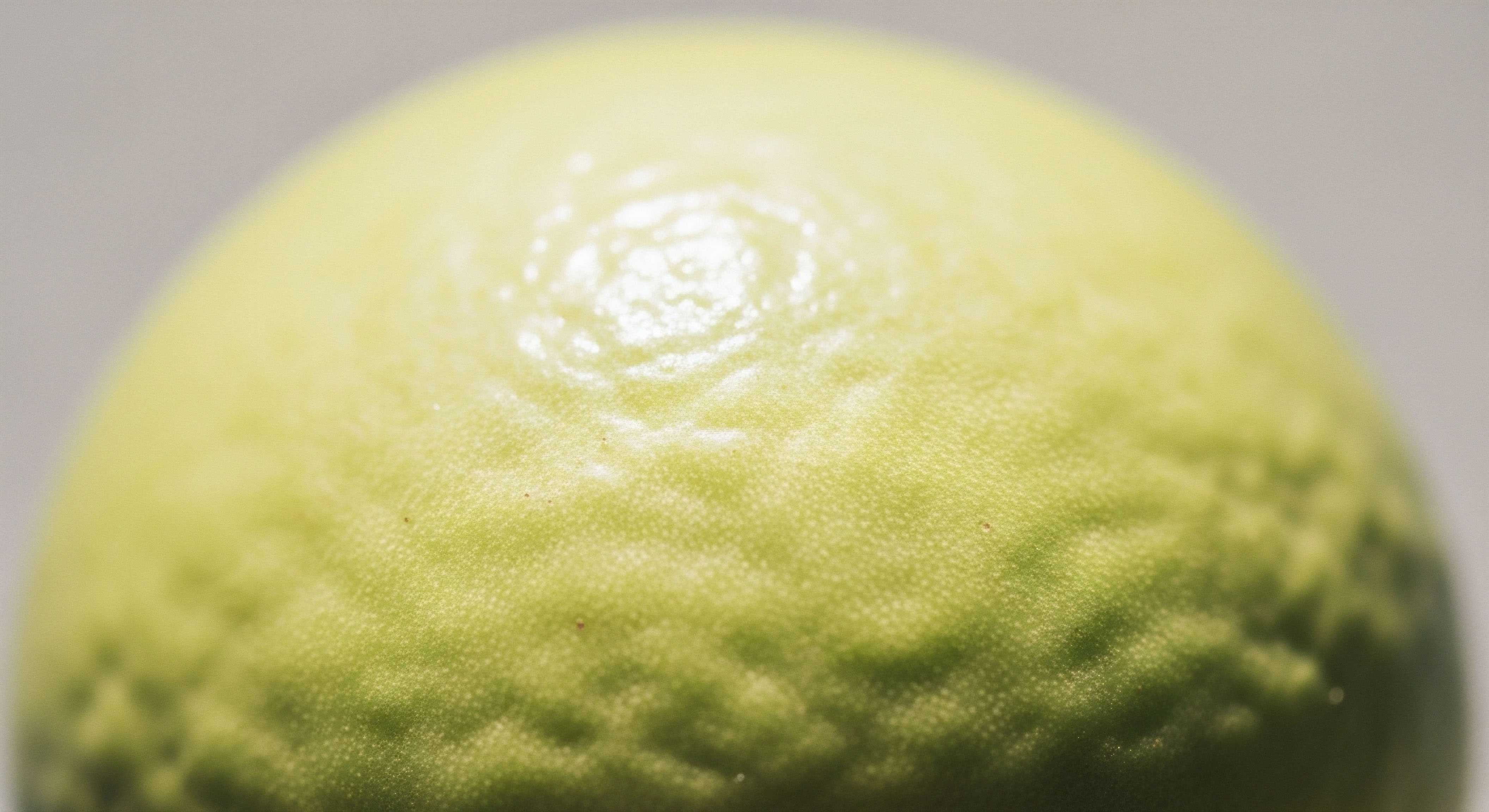

The principle of using only aggregated, de-identified data Meaning ∞ De-identified data refers to health information where all direct and indirect identifiers are systematically removed or obscured, making it impossible to link the data back to a specific individual. is the primary defense against discriminatory use. However, in the era of big data and advanced analytics, the concept of de-identification itself is under pressure. In smaller companies or departments, the risk of re-identification increases.

If a manager knows that only one team member participated in a smoking cessation program, and the aggregate data shows one smoker, the firewall becomes transparent. This potential for deductive disclosure is a vulnerability in the system. While HIPAA provides specific standards for de-identification, the increasing sophistication of data-linking techniques presents a continuous challenge to these safeguards.

The Specter of Proximal Discrimination

Beyond the direct, prohibited use of data, there is the risk of what could be termed “proximal discrimination.” This occurs when decisions are not officially based on protected health data but are influenced by observations or knowledge related to an employee’s participation in a wellness program.

For example, a manager might observe an employee frequently attending on-site nutrition counseling sessions. While the manager does not have access to the employee’s specific health data, this observation could subconsciously influence perceptions about the employee’s health status, reliability, or future healthcare costs.

This form of bias is insidious because it is difficult to prove and operates outside the formal data protection channels. It underscores the importance of not only technical and administrative safeguards but also robust training and a corporate culture that actively resists such inferences.

| Data Type | Permissible Use by Employer | Potential for Misuse or Systemic Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Individually Identifiable PHI | None for employment decisions. Access is legally prohibited. | Direct violation of HIPAA, GINA, and the ADA, leading to severe legal penalties. |

| De-Identified Aggregate Data | Program design, resource allocation, and reporting on overall workforce health trends. | Risk of re-identification in small employee populations; potential for drawing group-level conclusions that could influence broad policies. |

| Program Participation Data | Administering incentives and tracking engagement. | Potential for “proximal discrimination” where managers make inferences based on observed participation. |

The ongoing dialogue between the EEOC, the courts, and legislative bodies reflects the difficulty of maintaining equilibrium. Proposed rules have fluctuated, at times suggesting a “de minimis” limit for incentives for certain programs, while allowing for larger incentives for others. This demonstrates a continuous effort to calibrate the system.

The core challenge remains ∞ how to leverage the potential of wellness programs to improve public health without eroding the fundamental civil rights and privacy protections that have been established over decades. The integrity of the entire system relies on a multi-layered defense that includes not just legal compliance, but also ethical data stewardship and a vigilant awareness of the potential for subtle, yet impactful, forms of bias.

References

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. “What do HIPAA, ADA, and GINA Say About Wellness Programs and Incentives?” KFF, 2013.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “EEOC’s Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.” EEOC, 2016.

- Fisher & Phillips LLP. “Legal Compliance for Wellness Programs ∞ ADA, HIPAA & GINA Risks.” 2025.

- McDermott Will & Emery. “EEOC Releases Much-Anticipated Proposed ADA and GINA Wellness Rules.” 2021.

- Bresnick, Jennifer. “Employee wellness programs under fire for privacy concerns.” Health Data Management, 2017.

Reflection

You have now seen the intricate legal and ethical structures designed to protect your personal health information within the context of your employment. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It transforms you from a passive participant into an informed guardian of your own data.

The journey to wellness is profoundly personal, a path of understanding the unique biological systems that define your vitality. The legal framework is intended to honor and protect that journey. As you move forward, consider the nature of your own company’s programs. Observe the culture around health and privacy in your workplace.

This awareness is the first and most critical step in ensuring that your path to well-being remains distinctly your own, a source of strength and empowerment, fully shielded from the pressures of professional evaluation.