Fundamentals

The appearance of a letter from your employer detailing a new “wellness program” can land with a complex weight. On one hand, there is the stated goal of supporting your health. On the other, there is a distinct and unsettling pressure, a sense that your personal biological data is now a matter of workplace performance.

You may feel a tension between the private journey of managing your own body and the public demand to meet standardized health metrics. This feeling is a valid biological signal. The human body is a responsive system, and the introduction of external monitoring and financial penalties tied to deeply personal health outcomes activates ancient, hardwired stress pathways.

The subtle demand to lower your cholesterol, reduce your body mass index, or manage your blood pressure under the gaze of your employer is a profound psychological and physiological stressor. It introduces a variable of social and financial consequence into systems ∞ your endocrine, metabolic, and nervous systems ∞ that are designed to function in a state of equilibrium, a state known as homeostasis.

When this equilibrium is disturbed by chronic external pressure, the very biological markers these programs aim to improve can be negatively affected. The body’s primary stress hormone, cortisol, when chronically elevated, can directly contribute to insulin resistance, increased blood pressure, and the accumulation of visceral fat. Therefore, the architecture of a wellness program can, in some instances, create a biological paradox, potentially exacerbating the very conditions it purports to improve.

Understanding your rights in this context begins with recognizing a fundamental legal and biological truth your body is not a standardized machine. Federal laws, at their core, acknowledge this. The primary legal frameworks governing these programs are designed, in principle, to protect you from discrimination based on your unique health status.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) are foundational pillars of this protection. These laws establish that any participation in a wellness program that involves medical questions or examinations must be truly voluntary. The concept of “voluntary” is the central point of contention and legal scrutiny.

A program that imposes a significant financial penalty for non-participation can be interpreted as coercive, thus violating the principle of voluntary engagement. Your employer cannot require you to participate in such a program, nor can they retaliate against you for choosing not to.

This protection is a recognition that your health status, your genetic predispositions, and your personal medical history belong to you. These are not metrics of job performance. They are deeply personal data points in the complex, ever-evolving narrative of your own unique physiology.

The law further categorizes wellness programs into two distinct types, and this distinction is critical to understanding what your employer is permitted to do. The first and most straightforward type is a “participatory” wellness program. These programs reward you simply for taking part in an activity.

This might involve attending a health seminar, filling out a health risk assessment, or getting a biometric screening, without any regard to the results. For these programs, the rules are clear participation is the only requirement to receive the reward.

Your employer cannot penalize you based on your cholesterol levels, your weight, or any other health outcome derived from these activities. The reward is for the act of participating itself. This model respects your autonomy and privacy, encouraging engagement without imposing judgment or consequence on your biological reality.

The second category, and the one that introduces complexity and concern, is the “health-contingent” wellness program. These programs require you to meet a specific health goal to earn a reward or avoid a penalty. They are further divided into two subcategories.

“Activity-only” programs require you to perform a specific activity, such as walking a certain number of steps per day or completing a certain number of exercise sessions per week. “Outcome-based” programs require you to achieve a specific health outcome, such as lowering your blood pressure to a certain level or achieving a target BMI.

It is within this category of health-contingent programs that penalties and rewards are legally permitted, but they are subject to strict regulations. These regulations are designed to act as a guardrail, preventing these programs from becoming discriminatory tools.

The existence of these rules is an implicit acknowledgment that without them, such programs could unfairly penalize individuals for health outcomes that are often beyond their immediate control. The law attempts to strike a balance between allowing employers to encourage healthier lifestyles and protecting employees from being punished for their unique biological circumstances.

Intermediate

The legality of penalties within an employer-sponsored wellness program is governed by a complex interplay of federal statutes. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), as amended by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), provides the primary regulatory framework for health-contingent wellness programs.

These are the programs that can, under specific conditions, tie financial incentives or penalties to your health outcomes. To be compliant, a health-contingent program must adhere to five specific requirements. First, it must give individuals an opportunity to qualify for the reward at least once per year.

Second, the total reward or penalty is limited. For most programs, this is capped at 30% of the total cost of self-only health coverage. This limit can be increased to 50% for programs designed to prevent or reduce tobacco use.

Third, the program must be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” This means it cannot be a subterfuge for discrimination and must have a reasonable chance of improving health. Fourth, the full reward must be available to all similarly situated individuals. This leads to the fifth and most critical requirement the availability of a “reasonable alternative standard.”

The reasonable alternative standard is a cornerstone of employee protection within health-contingent programs. It acknowledges the biological reality that not everyone can meet a standardized health metric, regardless of their effort.

If it is unreasonably difficult due to a medical condition for you to meet the program’s goal, or if it is medically inadvisable for you to attempt to do so, your employer must provide you with an alternative way to earn the reward or avoid the penalty.

For an outcome-based program, this might mean your doctor certifies that you are under their care for the condition in question. For example, if the program requires a certain cholesterol level and yours remains high despite medical treatment, your doctor’s certification would satisfy the program’s requirement.

For an activity-only program, if you have a condition that prevents you from, say, participating in a running program, your employer might offer a swimming program or another suitable alternative. The employer must provide notice that a reasonable alternative standard is available. This provision is a direct countermeasure to prevent programs from penalizing individuals for having a medical condition.

The legal architecture of wellness programs distinguishes sharply between rewarding participation and penalizing health outcomes, with strict rules governing the latter.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) introduces another layer of critical protection. The ADA governs any wellness program that includes disability-related inquiries or medical examinations, which covers nearly all health-contingent programs and many participatory ones.

The central mandate of the ADA in this context is that such programs must be “voluntary.” The definition of “voluntary” has been a subject of significant legal debate. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which enforces the ADA, has struggled to reconcile the ACA’s allowance of substantial financial incentives (up to 30% or 50% of the cost of coverage) with the ADA’s requirement that participation not be coerced.

A large financial penalty can be seen as making a program functionally mandatory for employees who cannot afford the penalty, thus rendering it involuntary. This tension led to a lawsuit by the AARP against the EEOC, resulting in a court vacating the EEOC’s rules on incentive limits in 2019.

This has created a period of legal uncertainty. However, the core principle of the ADA remains participation cannot be required, and an employer cannot retaliate against you for not participating. Furthermore, the ADA requires that all medical information collected as part of a wellness program be kept confidential and maintained in separate medical files, not in your general personnel file.

Program Types and Legal Requirements

Understanding the classification of your employer’s wellness program is the first step in identifying your rights. The legal obligations of your employer are directly tied to the type of program they implement.

| Program Type | Description | Are Penalties Allowed? | Key Legal Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participatory | Rewards are given for participation, not for meeting a health goal. Examples include filling out a health assessment or attending a seminar. | No. Penalties cannot be based on health outcomes. | Must be made available to all similarly situated employees. If it involves medical exams, it must be voluntary under the ADA. |

| Health-Contingent (Activity-Only) | Requires completing an activity to earn a reward. Example ∞ a walking or exercise program. | Yes, within limits. | Must meet the five HIPAA/ACA requirements, including the 30%/50% incentive limit and offering a reasonable alternative standard. Must be voluntary under the ADA. |

| Health-Contingent (Outcome-Based) | Requires meeting a specific health outcome to earn a reward. Example ∞ achieving a certain BMI or blood pressure level. | Yes, within limits. | Must meet the five HIPAA/ACA requirements, including the 30%/50% incentive limit and offering a reasonable alternative standard. Must be voluntary under the ADA. |

What Is the Role of Genetic Information?

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) adds a final, crucial layer of protection. GINA prohibits employers and health insurers from discriminating against individuals based on their genetic information. This includes your family medical history and the results of any genetic tests.

In the context of wellness programs, GINA generally forbids employers from offering any financial incentive for you to provide your genetic information. There is a narrow exception if the information is used for a program that is part of a health plan, but the primary rule is that your genetic code is off-limits.

An employer cannot, for example, offer you a reward for completing a health risk assessment that asks about your family’s history of heart disease or cancer. This law is a powerful statement about the sanctity of your most personal biological data, recognizing that you should not be penalized or rewarded for a genetic blueprint you did not choose.

Academic

The central question of whether an employer can penalize an employee for failing to meet wellness program goals is, at its heart, a question of where the boundaries of corporate influence and individual biological autonomy lie. The legal framework, a patchwork of legislation from HIPAA, the ACA, the ADA, and GINA, attempts to draw this line.

However, the practical application of these laws reveals a deep philosophical and biological tension. The ACA, with its focus on cost containment, permits financial incentives that can reach thousands of dollars per year, creating a powerful behavioral lever.

The ADA, with its civil rights focus, insists that any program involving medical examination must be “voluntary.” The collision of these two principles creates a state of perpetual legal and ethical friction.

A financial penalty of $1,500 for failing to meet a biometric target may be presented as an “incentive,” but for a low-wage worker, it functions as a coercive mandate, transforming a “voluntary” program into a condition of affordable healthcare access. This was the core argument in the AARP v.

EEOC litigation, which led to the 2019 vacatur of the EEOC’s rules that had attempted to align the ADA’s “voluntary” standard with the ACA’s high incentive limits. The court found the EEOC had failed to provide a reasoned explanation for how a program could be considered voluntary when faced with such a steep penalty.

This judicial action left a regulatory void, pushing the analysis back to the fundamental statutes, where the inherent conflict remains unresolved. The result is an environment where employers operate with a degree of uncertainty, and employees are often unaware of the full extent of their protections.

The Physiological Fallacy of Standardized Metrics

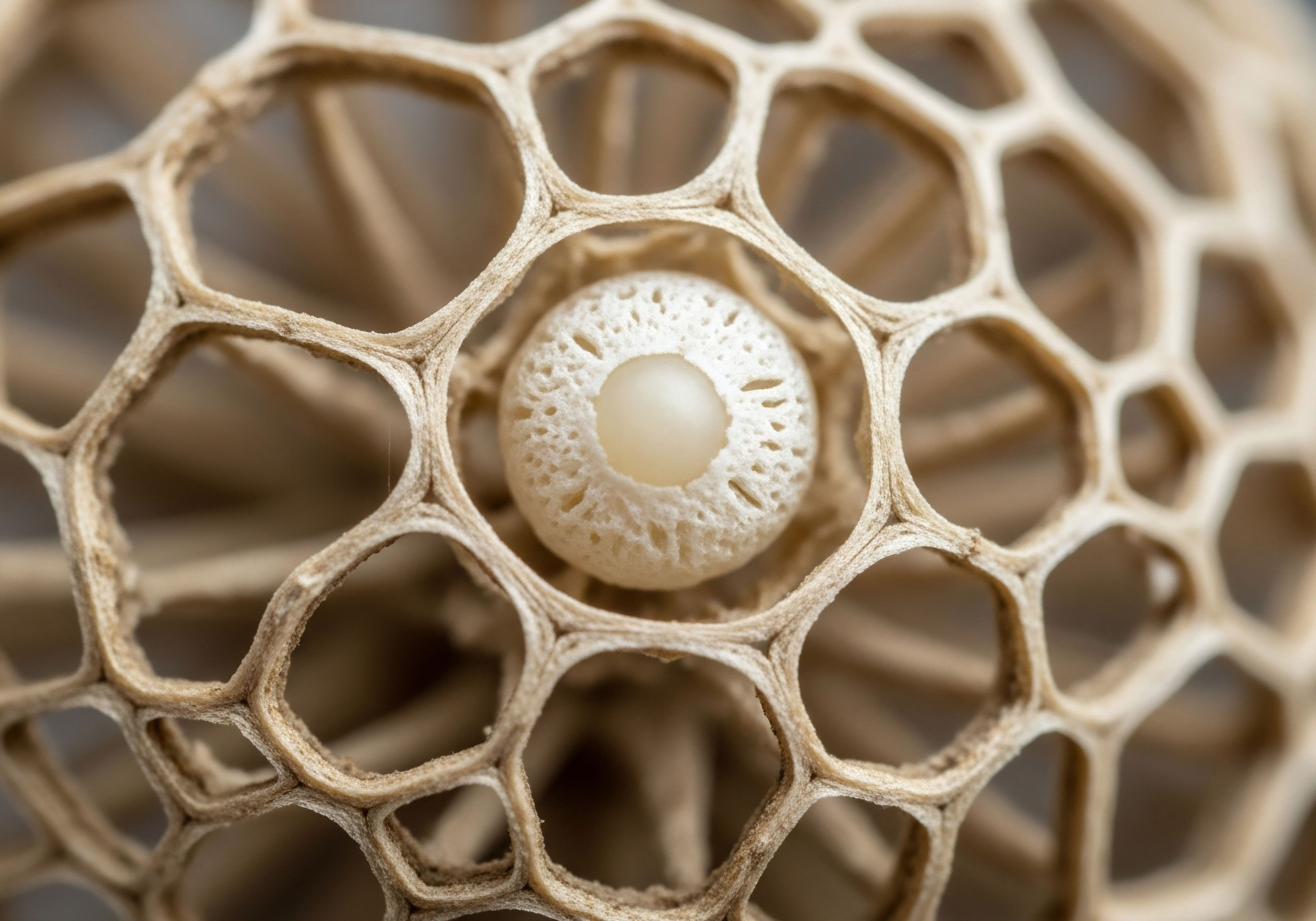

The entire premise of outcome-based wellness programs rests on a profound biological fallacy the idea that human health can be reduced to a handful of standardized, universally achievable biometric targets, and that failure to achieve them represents a failure of individual effort.

This perspective ignores the vast and complex web of systems that govern human physiology. A single biomarker, such as Body Mass Index (BMI) or a fasting glucose level, is not a simple input-output calculation. It is the emergent property of an intricate, dynamic, and highly individualized system of systems.

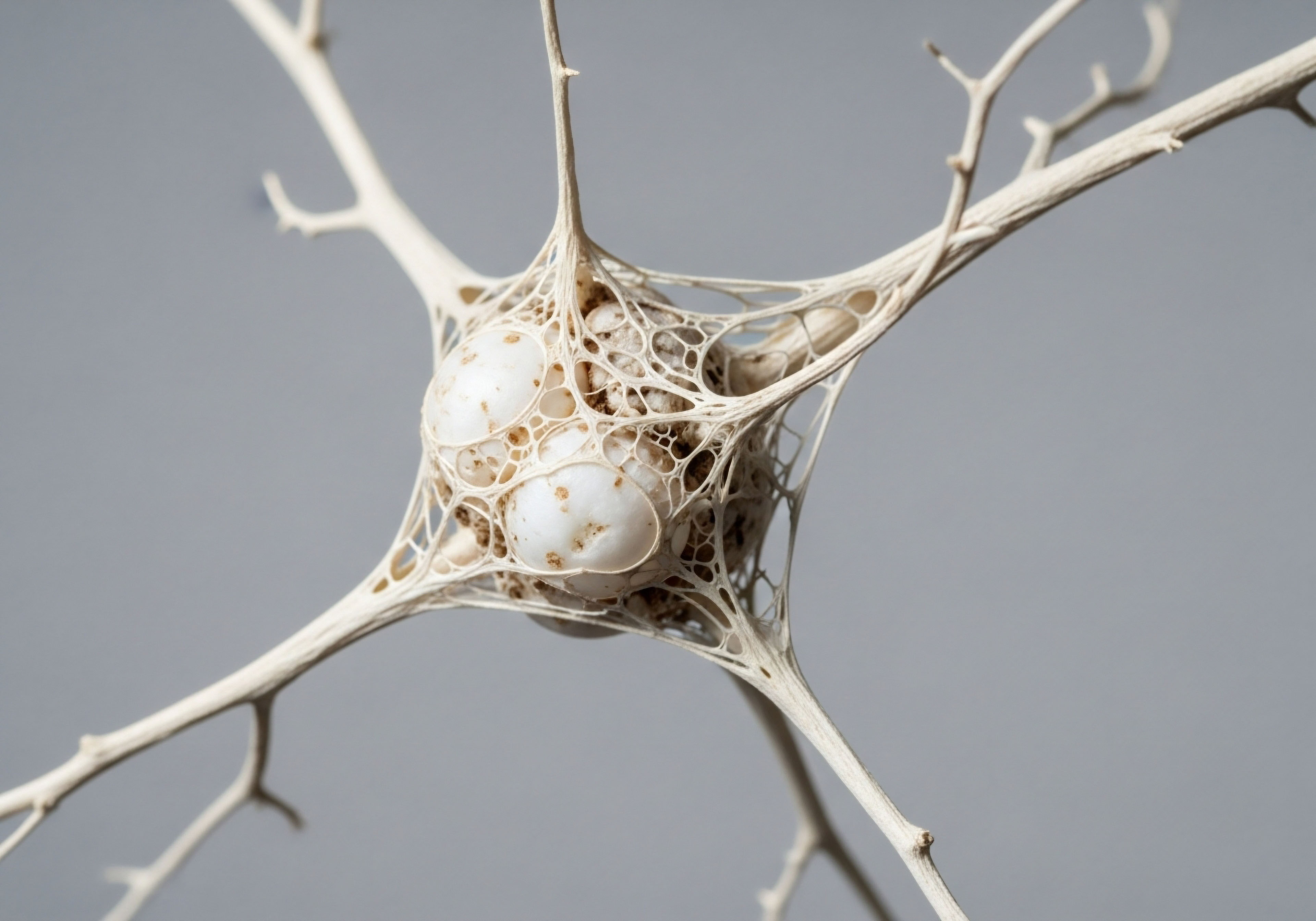

Consider the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system. Chronic workplace stress, which can be amplified by the pressure of a wellness program itself, leads to the persistent elevation of cortisol. Elevated cortisol has well-documented effects on metabolic health. It promotes gluconeogenesis in the liver, increasing blood sugar levels.

It enhances the storage of visceral adipose tissue, the metabolically active fat that surrounds internal organs and is a key driver of inflammation and insulin resistance. It can also dysregulate appetite-controlling hormones like ghrelin and leptin, leading to increased hunger and cravings for energy-dense foods.

An employee struggling to meet a weight or blood sugar goal may be fighting a battle against their own stress-induced physiology, a battle that cannot be won through simple caloric restriction or willpower. The program, in this context, becomes an iatrogenic intervention, a treatment that causes harm.

The demand for uniform health outcomes ignores the fundamental biological principle of individual variation in metabolic and endocrine function.

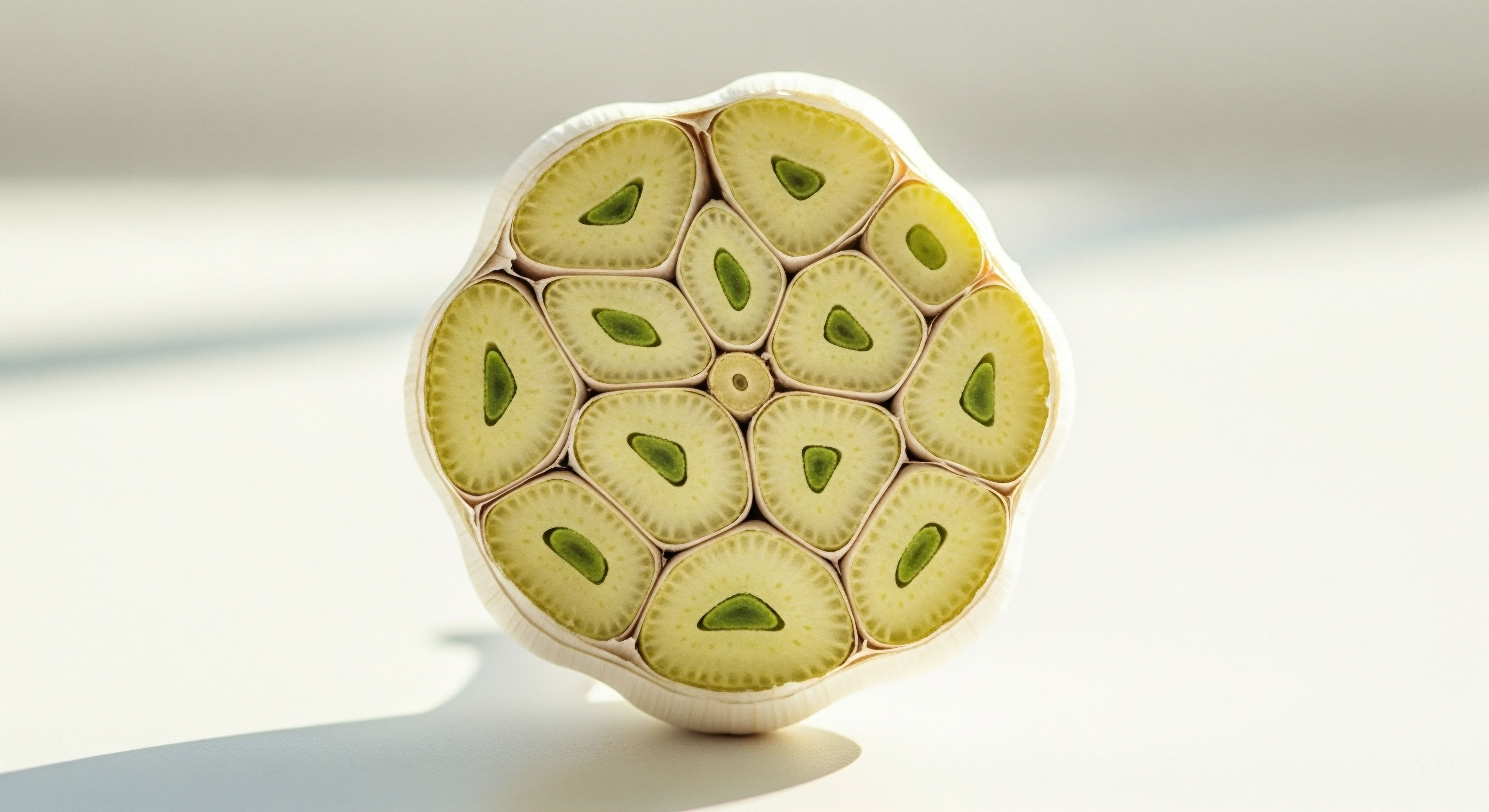

Furthermore, the endocrine system does not operate in a vacuum. An individual’s ability to regulate weight, blood pressure, and cholesterol is profoundly influenced by their hormonal milieu, particularly thyroid hormones and sex hormones. Hypothyroidism, a common and often undiagnosed condition, slows the body’s metabolic rate, making weight loss extraordinarily difficult.

In women, the transition to perimenopause and menopause involves a dramatic fluctuation and eventual decline in estrogen and progesterone, which is associated with a shift in fat storage to the abdomen and an increase in insulin resistance. In men, age-related decline in testosterone is linked to decreased muscle mass, increased fat mass, and a higher risk of metabolic syndrome.

These are not matters of lifestyle choice; they are fundamental shifts in the body’s operating system. To penalize an individual for a BMI that is influenced by a sub-optimal TSH level or a natural decline in estradiol is to penalize them for their biology.

A Deeper Look at Compliance Requirements

The five core requirements for health-contingent wellness programs under HIPAA and the ACA represent a legal attempt to impose fairness on a biologically complex issue. A closer examination reveals their intent and limitations.

- Frequency ∞ The requirement for an annual opportunity to qualify prevents a single “failure” from permanently locking an employee out of a reward. It acknowledges that health is dynamic.

- Size of Reward ∞ The 30% and 50% caps are an attempt to balance incentive with coercion. The ongoing legal debate shows that this balance is precarious and may not adequately protect vulnerable employees.

- Reasonable Design ∞ A program must be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” This clause could be used to challenge programs based on outdated or overly simplistic science, such as an exclusive focus on BMI without considering body composition.

- Uniform Availability and Reasonable Alternative Standards ∞ These two requirements work in tandem. They are the primary legal shield for individuals whose medical conditions prevent them from meeting the standard goals. The onus is on the employer to provide a feasible alternative. This is the most powerful tool an employee has to challenge an unfair penalty.

Legal Precedents and the Path Forward

The legal landscape has been shaped by key cases. The Yale University settlement, where the university agreed to pay $1.29 million and suspend opt-out fees for its wellness program, highlighted the risks for employers who impose significant penalties. The lawsuit alleged that the $1,300 annual penalty for non-participation was coercive and violated the ADA and GINA.

While Yale admitted no wrongdoing, the settlement and program changes were significant. Cases like this, along with the AARP’s successful challenge to the EEOC rules, signal a growing judicial skepticism toward highly punitive wellness programs. The future of wellness program regulation will likely involve a more sophisticated understanding of coercion and a greater emphasis on protecting employee privacy and autonomy.

The focus may shift away from outcome-based penalties and toward programs that provide resources, support, and education without financial threat, recognizing that true wellness is fostered through empowerment, not compulsion.

| Statute | Primary Domain | Key Protection in Wellness Programs |

|---|---|---|

| HIPAA / ACA | Group Health Plans | Limits incentive/penalty size (30-50%) and mandates “reasonable alternative standards” for health-contingent programs. |

| ADA | Disability Discrimination | Requires programs with medical exams to be “voluntary.” Mandates confidentiality of medical information and reasonable accommodations. |

| GINA | Genetic Discrimination | Prohibits incentives for providing genetic information, including family medical history. |

References

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). EEOC’s Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act. EEOC-CVG-2016-2.

- U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, & U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2013). Final Rules Under the Affordable Care Act for Nondiscriminatory Workplace Wellness Programs. Federal Register, 78(106), 33158-33193.

- AARP v. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 267 F. Supp. 3d 14 (D.D.C. 2017).

- Snyder, M. L. (2022). The Risks of Employee Wellness Plan Incentives and Penalties. Davenport, Evans, Hurwitz & Smith, LLP.

- Madison, K. M. (2016). The Law, Policy, and Ethics of Employers’ Use of Financial Incentives to Promote Employee Health. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 44(1), 52-57.

- Schmidt, H. & Shel-Or, C. (2017). Coercion and incentives in workplace wellness programs. The American Journal of Bioethics, 17(10), 63-65.

- Robbins, S. P. & Judge, T. A. (2019). Organizational Behavior (18th ed.). Pearson.

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers ∞ The Acclaimed Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping. Holt Paperbacks.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the legal and biological landscape you inhabit as an employee. This knowledge is a tool. It is the first step in recalibrating the power dynamic between you and the programs that seek to quantify your health.

Your body tells a story far more complex than any single biometric screening can capture. It is a narrative written in the language of hormones, neurotransmitters, and metabolic pathways, influenced by your genetics, your environment, and your personal history. The journey toward vitality is one of deep, personal inquiry.

It involves listening to your body’s signals, understanding its unique needs, and building a personalized protocol for wellness. This path requires a partnership with healthcare providers who see you as an individual system, not a set of population averages.

Armed with an understanding of your rights and a deeper appreciation for your own biological complexity, you are positioned to advocate for yourself. You can now engage with these programs from a place of informed autonomy, making choices that honor the intricate, personal nature of your own health journey.

Glossary

wellness program

blood pressure

genetic information nondiscrimination act

americans with disabilities act

wellness programs

health-contingent programs

health-contingent wellness

financial incentives

reasonable alternative standard

reasonable alternative

americans with disabilities

equal employment opportunity commission