Fundamentals

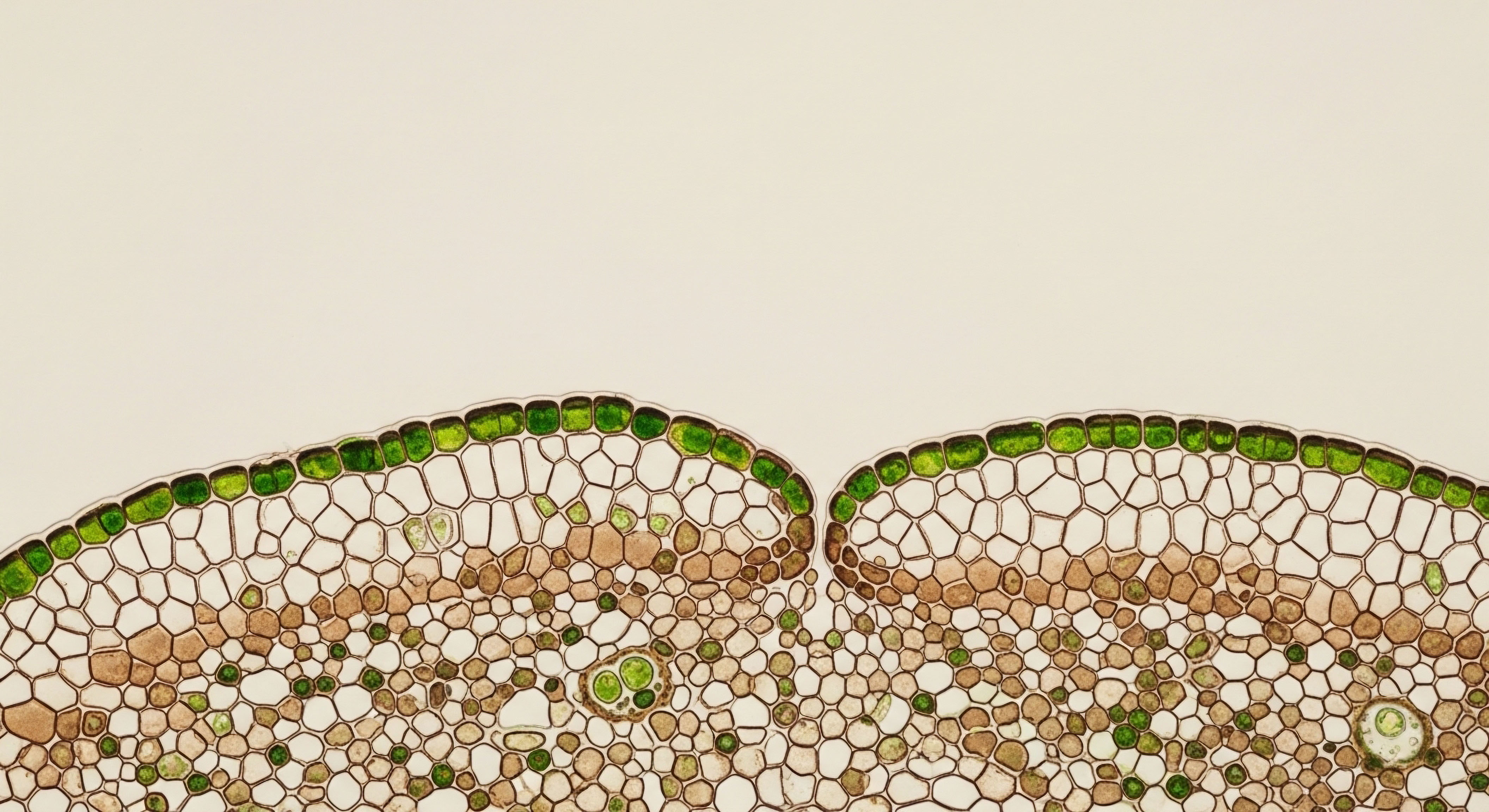

The question of whether an employer can mandate participation in a wellness program touches upon a sensitive intersection of personal health autonomy and workplace policy. Your well-being is an intricate, personal system, and any external program must honor that individuality.

The law provides a framework designed to protect your rights, ensuring that participation in such programs remains a choice, not a condition of employment. This legal structure recognizes that true wellness cannot be coerced; it must be a voluntary pursuit.

The legislative guardrails in place, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), are designed to prevent discrimination and protect your private health information. These laws ensure that while an employer can encourage healthier habits, they cannot penalize you for choosing not to participate in a wellness program. The emphasis is on providing opportunities for health improvement, not on creating a system of coercion.

The Principle of Voluntary Participation

At the heart of the legal framework governing workplace wellness programs is the principle of voluntary participation. This means that you, as an employee, cannot be required to participate in a wellness program, nor can you be penalized for declining to do so.

Your employer can offer incentives to encourage participation, but these incentives must be carefully structured to avoid becoming coercive. The goal is to create a system where you are empowered to make choices about your health without fear of negative consequences in the workplace.

This principle is rooted in the understanding that your health is a personal matter, and any decisions about it should be made freely and without pressure. The law recognizes that a wellness program is only truly beneficial when it is embraced willingly, as a tool for personal growth and not as a mandatory obligation.

Understanding the Legal Protections

Several key pieces of federal legislation work together to protect your rights in the context of workplace wellness programs. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities and requires that wellness programs be voluntary. This means that you cannot be denied health insurance or be subject to any adverse employment action for not participating.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) protects you from discrimination based on your genetic information, which includes your family medical history. Under GINA, your employer cannot require you to provide genetic information, and any collection of such information as part of a wellness program must be voluntary and with your written consent.

Finally, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) establishes standards for the privacy and security of your health information, ensuring that any data collected through a wellness program is kept confidential and used appropriately.

Your employer can encourage, but not compel, your participation in a wellness program, with federal laws in place to prevent discrimination and protect your privacy.

Types of Wellness Programs

Workplace wellness programs generally fall into two categories ∞ participatory and health-contingent. Understanding the distinction between these two types of programs is essential for comprehending your rights and your employer’s obligations. Each type of program is subject to different legal requirements, particularly concerning the use of incentives and the need for reasonable accommodations.

Participatory Wellness Programs

Participatory wellness programs are those that do not require you to meet a health-related standard to earn a reward. Examples include attending a health seminar, participating in a smoking cessation program, or completing a health risk assessment without any requirement for specific results.

These programs are generally subject to fewer legal restrictions because they are seen as less likely to be discriminatory. The focus is on participation itself, rather than on achieving a particular health outcome. This approach encourages engagement and education without creating pressure to meet specific health targets that may be difficult for some individuals to achieve.

Health-Contingent Wellness Programs

Health-contingent wellness programs, on the other hand, require you to meet a specific health-related goal to earn a reward. These programs are further divided into two subcategories ∞ activity-only and outcome-based.

An activity-only program might require you to walk a certain number of steps each day, while an outcome-based program might require you to achieve a certain body mass index (BMI) or cholesterol level. Because these programs tie rewards to specific health outcomes, they are subject to stricter legal requirements to ensure they do not discriminate against individuals with medical conditions or disabilities.

These requirements include providing reasonable alternatives for individuals who are unable to meet the specified goals due to a medical condition.

Intermediate

The legal framework governing employer-sponsored wellness programs is a complex interplay of federal statutes designed to balance an employer’s interest in promoting a healthy workforce with an employee’s right to privacy and autonomy.

While employers can encourage participation in wellness programs through the use of incentives, these programs must be carefully designed to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

These laws work in concert to ensure that wellness programs are voluntary, non-discriminatory, and protective of employees’ confidential health information. The degree of regulation a wellness program is subject to often depends on its design, specifically whether it is a “participatory” or “health-contingent” program. Understanding the nuances of these legal requirements is essential for both employers seeking to implement effective and compliant wellness initiatives and for employees seeking to understand their rights.

Incentives and the Definition of “voluntary”

A central issue in the regulation of wellness programs is the extent to which incentives can be used without rendering a program “involuntary.” The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has provided guidance on this issue, establishing limits on the value of incentives that can be offered.

For a wellness program to be considered voluntary under the ADA, the incentive offered cannot be so substantial that it could be considered coercive. The EEOC has set the incentive limit at 30% of the total cost of self-only health coverage.

This limitation is intended to ensure that employees do not feel financially compelled to participate in a program that requires them to disclose sensitive health information or undergo medical examinations. The concept of “voluntary” is thus not merely about the absence of a direct mandate, but also about the absence of undue financial pressure.

What Are the Incentive Limits for Different Types of Programs?

The 30% incentive limit applies to both participatory and health-contingent wellness programs that are part of a group health plan. However, there are some nuances to this rule. For example, a smoking cessation program that simply asks employees whether they use tobacco can offer an incentive of up to 50% of the cost of self-only coverage.

If the program requires a biometric screening to test for nicotine use, the 30% limit applies. The table below summarizes the incentive limits for different types of wellness programs.

| Program Type | Incentive Limit |

|---|---|

| Participatory Wellness Program | 30% of the cost of self-only coverage |

| Health-Contingent Wellness Program (Activity-Only) | 30% of the cost of self-only coverage |

| Health-Contingent Wellness Program (Outcome-Based) | 30% of the cost of self-only coverage |

| Smoking Cessation Program (No Biometric Screen) | 50% of the cost of self-only coverage |

Reasonable Accommodations and Alternative Standards

For health-contingent wellness programs, the law requires that employers provide reasonable accommodations or alternative standards for individuals who are unable to meet the program’s requirements due to a medical condition. This is a critical component of ensuring that wellness programs are non-discriminatory.

For example, if a program requires participants to walk a certain number of steps per day, an employee with a mobility impairment must be offered an alternative way to earn the reward, such as participating in a stretching program or attending a nutrition class. The alternative standard must be reasonable and attainable for the individual, and the employer cannot require a doctor’s note unless it is medically necessary.

To ensure fairness, the law mandates that employers offer reasonable alternatives to individuals who cannot meet a wellness program’s requirements due to a medical condition.

Confidentiality of Health Information

The confidentiality of your health information is a paramount concern in the context of workplace wellness programs. Both the ADA and HIPAA have strict rules about how your health information can be collected, used, and disclosed. Any health information collected as part of a wellness program must be kept confidential and separate from your personnel records.

Your employer should only receive aggregated data that does not identify individual employees. You cannot be required to waive your confidentiality rights as a condition of participating in a wellness program or receiving an incentive. These protections are in place to ensure that your sensitive health information is not used to make employment decisions or for any other discriminatory purpose.

- Data Security ∞ Employers must implement robust security measures to protect the confidentiality of your health information.

- Limited Access ∞ Access to your health information should be limited to authorized personnel who have a legitimate need to know.

- Third-Party Vendors ∞ If your employer uses a third-party vendor to administer the wellness program, the vendor must also comply with all applicable privacy and security requirements.

Academic

The legal architecture governing employer-sponsored wellness programs represents a dynamic and often contentious area of law, reflecting the inherent tension between public health objectives and individual civil liberties. The regulatory landscape, primarily shaped by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), has been the subject of significant legal challenges and scholarly debate.

At the heart of this debate lies the interpretation of “voluntary” participation, particularly in the context of financial incentives that may induce employees to disclose sensitive health and genetic information. The judiciary’s role in adjudicating these matters has been pivotal, with courts grappling to define the permissible boundaries of employer influence over employee health decisions.

An examination of key legal precedents reveals the evolving judicial interpretation of the statutory framework and the ongoing struggle to reconcile the competing interests at play.

Judicial Scrutiny of EEOC Regulations

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has been at the forefront of regulating workplace wellness programs, issuing rules to clarify the application of the ADA and GINA. However, these regulations have not been without controversy. In AARP v.

EEOC, the AARP successfully challenged the EEOC’s 2016 final rules, arguing that the 30% incentive limit was arbitrary and did not render the programs truly “voluntary.” The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia agreed, finding that the EEOC had failed to provide a reasoned explanation for its conclusion that the 30% incentive level was consistent with the voluntary participation requirement of the ADA and GINA.

The court vacated the rules, effective January 1, 2019, creating a period of legal uncertainty for employers. This case underscores the judiciary’s role in holding administrative agencies accountable and ensuring that their regulations are grounded in a reasonable interpretation of the law.

What Was the Court’s Rationale in AARP V EEOC?

The court in AARP v. EEOC focused on the EEOC’s failure to justify its 30% incentive limit. The court noted that the EEOC had not provided any data or analysis to support its conclusion that this level of incentive would not be coercive for a significant number of employees.

The court also pointed out that the EEOC had not adequately explained how it reconciled the 30% limit with the ADA’s requirement that wellness programs be “voluntary.” The court’s decision highlights the importance of evidence-based rulemaking and the need for administrative agencies to provide a clear and coherent rationale for their regulatory choices. The vacating of the rules has left a regulatory void, forcing employers to navigate a complex and uncertain legal landscape.

The “safe Harbor” Provision and Its Limitations

The ADA includes a “safe harbor” provision that exempts certain insurance plans from the statute’s general prohibitions. Some employers have argued that this safe harbor provision should apply to wellness programs that are part of a group health plan, thereby exempting them from the ADA’s voluntariness requirement.

However, the EEOC has consistently rejected this interpretation, and courts have generally deferred to the agency’s position. In EEOC v. Flambeau, Inc. the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals declined to rule on the merits of the case, but the district court had previously held that the ADA’s safe harbor provision did apply to the employer’s wellness program.

This issue remains a point of legal contention, with employer advocacy groups continuing to push for a broader interpretation of the safe harbor provision. The resolution of this issue will have significant implications for the future regulation of workplace wellness programs.

The ongoing legal debate over the ADA’s “safe harbor” provision reflects the broader struggle to define the scope of employer-sponsored wellness programs and their relationship to anti-discrimination laws.

The Ethics and Efficacy of Wellness Programs

Beyond the legal considerations, there is a growing body of academic literature examining the ethical and practical implications of workplace wellness programs. Studies have raised concerns about the potential for these programs to be discriminatory, particularly against individuals with chronic health conditions or those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

There is also a debate about the effectiveness of these programs in actually improving employee health and reducing healthcare costs. Some studies have found limited evidence of positive health outcomes, while others have suggested that the return on investment for employers may be overstated.

These findings raise important questions about the underlying assumptions and motivations behind the push for workplace wellness programs, and whether they represent a genuine commitment to employee well-being or a more cynical attempt to shift healthcare costs onto employees.

- Principle of Autonomy ∞ The right of individuals to make their own decisions about their health and well-being.

- Principle of Beneficence ∞ The obligation of employers to act in the best interests of their employees and to ensure that wellness programs are designed to be beneficial.

- Principle of Justice ∞ The need to ensure that wellness programs are fair and equitable, and do not create or exacerbate health disparities.

| Ethical Principle | Application to Wellness Programs |

|---|---|

| Autonomy | Employees should have the right to choose whether or not to participate in a wellness program without coercion or undue influence. |

| Beneficence | Wellness programs should be based on sound scientific evidence and be designed to produce tangible health benefits for employees. |

| Non-maleficence | Wellness programs should not harm employees, either physically or emotionally, and should not create a culture of blame or stigma. |

| Justice | Wellness programs should be accessible to all employees, regardless of their health status, disability, or socioeconomic background. |

References

- Mattke, S. Liu, H. Caloyeras, J. P. Huang, C. Y. Van Busum, K. R. & Khodyakov, D. (2013). Workplace wellness programs study. Rand Corporation.

- Song, Z. & Baicker, K. (2019). Effect of a workplace wellness program on employee health and economic outcomes ∞ a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 321 (15), 1491-1501.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. Federal Register, 81(103), 31143-31156.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Federal Register, 81(103), 31125-31143.

- Madison, K. M. (2016). The law, policy, and ethics of employers’ use of financial incentives to promote employee health. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 44 (3), 451-468.

- Horwitz, J. R. Kelly, B. D. & DiNardo, J. E. (2013). Wellness incentives, health insurance, and the future of health care cost containment. The Milbank Quarterly, 91 (1), 7-26.

- AARP v. EEOC, 267 F. Supp. 3d 14 (D.D.C. 2017).

- EEOC v. Flambeau, Inc. 846 F.3d 941 (7th Cir. 2017).

- Kinzer, M. H. (2018). Workplace wellness programs ∞ A review of the legal landscape. Employee Relations Law Journal, 44 (1), 5-21.

- Schmidt, H. & Gerber, A. (2017). The ethics of workplace wellness programs. The Hastings Center Report, 47 (3), 11-21.

Reflection

The journey to understanding your health is a deeply personal one. The information presented here provides a map of the legal landscape surrounding workplace wellness programs, but it is you who must navigate the terrain of your own well-being.

The knowledge you have gained is a tool, empowering you to make informed decisions and to advocate for your own health interests. As you move forward, consider how you can use this understanding to engage with your employer’s wellness offerings in a way that feels authentic and supportive of your unique health goals.

The path to vitality is not a one-size-fits-all prescription, but a personalized protocol that you have the power to shape. What will be your next step in this journey?

Glossary

wellness program

genetic information nondiscrimination act

americans with disabilities act

workplace wellness programs

voluntary participation

workplace wellness

wellness programs

genetic information nondiscrimination

genetic information

health information

health insurance

reasonable accommodations

participatory wellness programs

smoking cessation program

health-contingent wellness programs

governing employer-sponsored wellness programs

ensure that wellness programs

equal employment opportunity commission

incentive limit

health-contingent wellness

self-only coverage

employee health

aarp v. eeoc

safe harbor provision